SATURDAY MORNING ANIMATION CLUB

Curated by Petra Széman in partnership with isthisit? and Off Site Project

Supported by Arts Council England

Saturday June 11, 18, 25 2022

Saturday July 2, 9 2022

online (registration required, see below for details and links)

Saturday Morning Animation Club is a terrific screening/talk series taking place over five consecutive Saturday mornings, featuring new works by Emily Mulenga, Petra Szemán, David Blandy, Christian Wright, and Bob Bicknell-Knight. Each screening will be followed by a second presentation featuring a commentary by the artist, and will conclude with a Q&A session. The curators’ goal is “to re-capture the excitement of watching cartoons over the weekend and celebrate all forms of fandom”.

Full details

Saturday Morning Animation Club is a series of screenings + talks across five weeks between 11 June - 9 July, showcasing films by people who wield the dual powers of being an artist and a nerd.

Unified by an early fascination and involvement with anime and games, each artist focuses in on the worlds and perspectives fandom allows for. From this angle the five videos broaden ideas of human and non-human perception, screen-based experiences, virtual worlds and alternative ways of being.

Join us on Saturday mornings for a screening of new video commissions by Emily Mulenga, Petra Szemán, David Blandy, Christian Wright and Bob Bicknell-Knight respectively, followed by a little insider walkthrough and a Q&A (via Zoom).

Tied together by a refusal to downplay the enthusiasms and generative energy of fandom, Saturday Morning Animation Club will lead viewers through iterations of animatic worlds, on- and off-screen, with or without player input. The screening series has been produced in collaboration with web projects isthisit? and Off Site Project. Attendance of all five screenings will be rewarded with a special prize.

The videos were commissioned using funding from Arts Council England as part of On Animatics, a cross-disciplinary project exploring the murky overlapping areas of contemporary art, animation, fandom, avatars and virtual worlds.To conclude the project, the book WEEB THEORY will be released later this year with Banner Repeater, edited by Petra Szemán and Jamie Sutcliffe.

Featured artwoks

June 11 2022, Emily Mulenga, Main Character (2022)

Main Character centres around the Bunny as she experiences the abrupt end of her relationship, set against the backdrop of her life in a cyberpunk city and her evening gig as a singer. Whilst the event tears a hole in the fabric of her reality, it leads to reflections on the nature of being and what can be discovered underneath surface appearances. Flipping between 3D visuals, 2D animation and live action footage, Emily’s film takes inspiration from cartoons, video games and music videos as means to navigate the character’s relationship to life.

June 18 2022, Petra Szemán, Openings !!! (2022)

Inhabiting the interstitial zones of anime credit sequences, video game loading screens and regional train journeys, Petra Szemán’s Openings !!! intensifies the gaps between the layers of animated imagery in an attempt to grasp the kinds of experience that may lie beyond human perceptual boundaries. The video follows the protagonist ‘Yourself’ as they ride local trains through intermedial landscapes. From this uniquely conceived and drafted kinetic viewpoint, fragments of different worlds segue into view, signalling perceptual ruptures that seemingly force subjectivity outside of itself, into strange new relationships of interdependency and intoxication with the moving image.

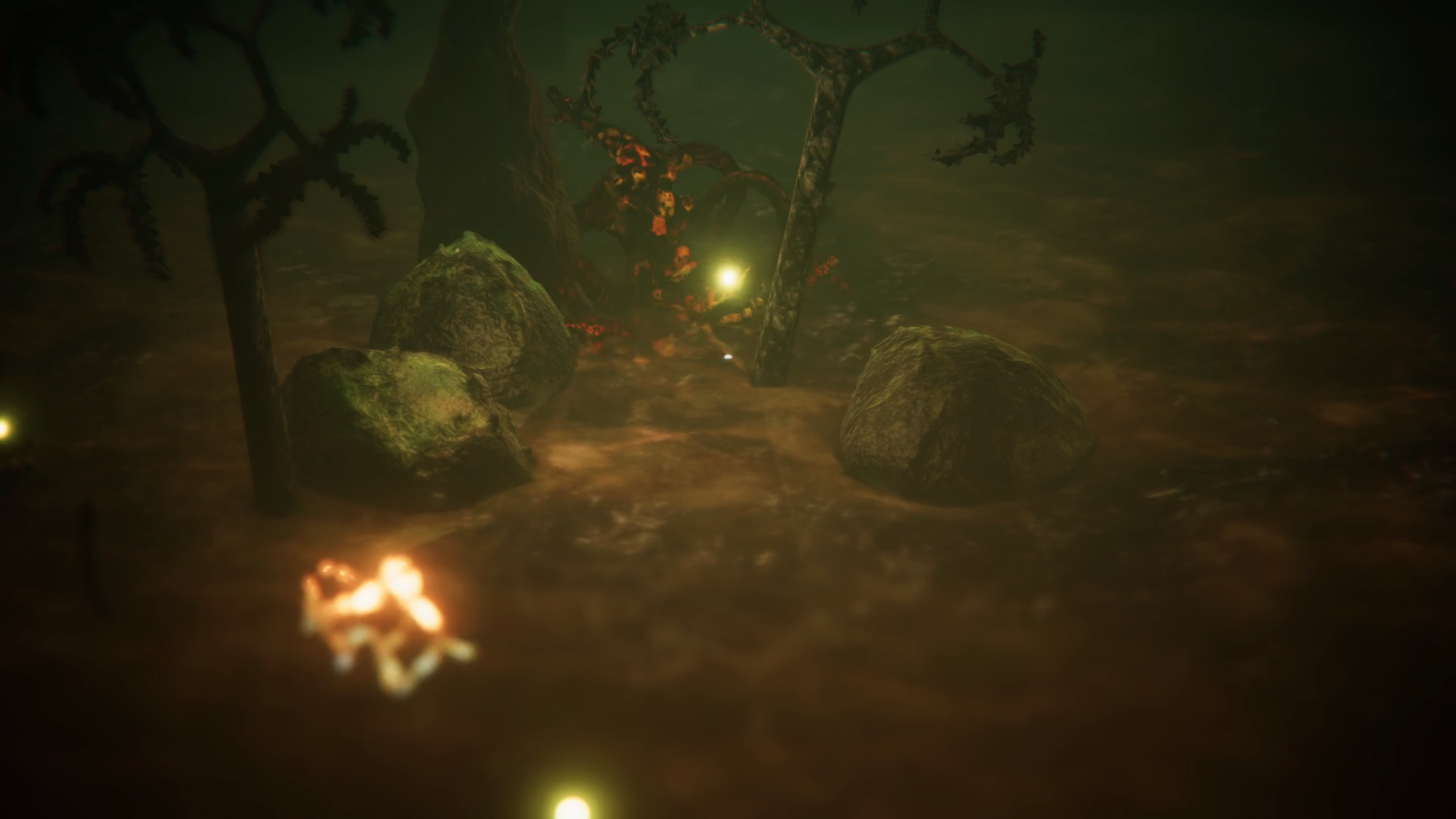

June 25 2022, David Blandy, Androids Dream (2022)

In Androids Dream, Blandy deconstructs the cyberpunk aesthetic first prototyped by Gibson’s Neuromancer (1984) and Scott’s Blade Runner (1982), and which has continued to be repeated and become ever more ossified. Formed of multiple simulacra, the work involves Unreal Engine assets, uses Kojima’s Snatcher - itself a replay of Blade Runner in videogame form - and even deploys an algorithmic mimesis of the artist's own voice. Breaking down the aesthetic form, the film in turn breaks down, repeats, refracts, and goes into reverse.

July 02 2022, Christian Wright, Body Language (2022)

Primarily shot within the video game Dark Souls III (2016), Body Language tells the story of an epic encounter between two online players. Focusing on how the combatants communicate via the limited body language afforded to them by the game design and the performative traditions of gaming communities, Christian’s film combines the grandiosity of cinema with the janky awkwardness of gameplay. The result is both reminiscent of videos produced and shared in insular fan communities, while also relating to a burgeoning contemporary art and academic context.

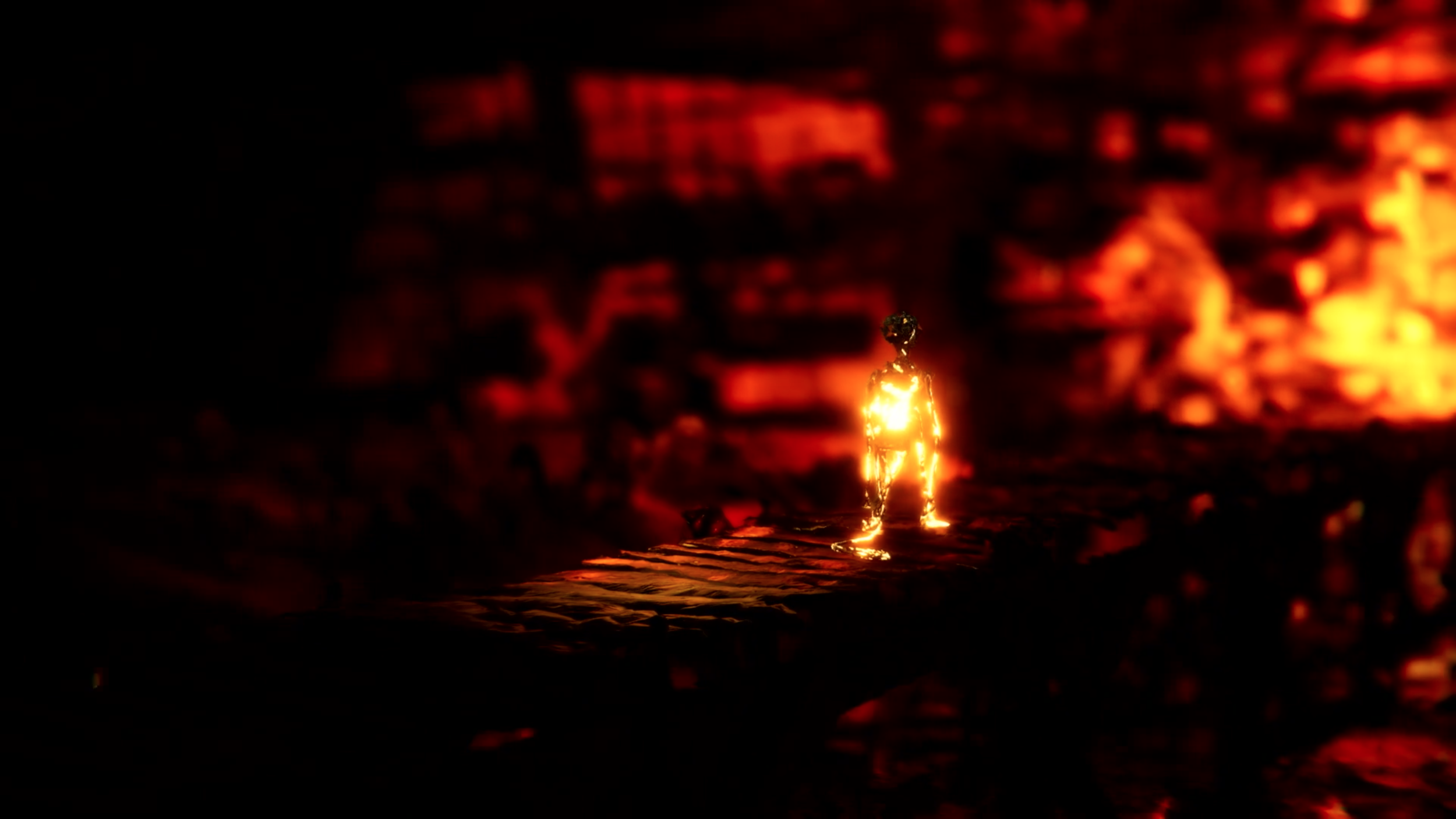

July 09 2022, Bob Bicknell-Knight, Non-Player Character (2022)

A looping CGI video, Bob’s Non-Player Character explores the NPC as a vehicle by which we can understand human navigation of an increasingly codified and controlled existence. Controlled by the AI software, NPCs have predetermined sets of behaviours. Doomed to repeat the same day their lives revolve around the player, waiting for interaction. Bob’s film imagines what enemy NPCs are thinking and feeling, forced to be defeated over and over, until their data becomes unreadable.

Featured artists

Emily Mulenga (b. 1991, England) is a multimedia artist who imagines what a digital utopia might look like from a feminist and milennial perspective. Her output is the result of a ravenous media diet, blending the high polish aesthetics of MTV with the jagged polygons of early PlayStation games; mixing YouTube video conventions with lo-fi social media posts of her online contacts. Contributing to the excessive circulation of digital matter, she considers how the blurring between human and machine changes experiences of womanhood, and how becoming cyborg is both a fantasy and reality, the future and the present. (instagram)

Petra Szemán (b. 1994, Gateshead) is a moving image artist whose practice focuses on the murky borderlands along the arbitrary separation of the real and the fictional. Using a virtual version of themself as a protagonist journeying through animatic realms, they explore liminal spaces and threshold situations, looking to dissect the ways our memories and selves are constructed within a fictionally oversaturated landscape (both on- and off-screen). Turning away from considering cyberspace as a radically ‘other’ realm, Petra walks the line between dystopian and utopian frameworks, eyes set on new queer horizons. (instagram)

David Blandy (b. 1976, Brighton) investigates the stories and cultural forces that inform and influence our behaviour. Through a gaming art practice he has written original RPGs that address issues of social justice, climate change and our potential posthuman futures. Collaboration is central to his practice, used as a means to examine communal and personal heritage, as well as forms of interdependence. His practice ranges from installation, performance, writing, gaming and sound. He has had national and international solo exhibitions, and is represented by Seventeen Gallery, London. (instagram)

Christian Wright

Christian Wright (b. 1993, Newcastle upon Tyne) is a digital media artist working with video games and animated assets to blend cinematic and machinima visual languages. Through this frame, he looks at how the boundaries of normal play are stretched by the performative actions of players themselves. Whether it be the intimate physical interactions of online multiplayer, the choreographed quest for perfection of speedrunning, or the mimetic act of digital cosplay within character creators, Christian places community driven gestures at the forefront. (instagram)

Bob Bicknell-Knight (b. 1996, Suffolk) is a multidisciplinary artist, curator and writer influenced by surveillance capitalism and responding to internet hyper consumerism, automation and technocratic authoritarianism. Within his practice he harnesses different processes and materials to create both physical and digital artworks, including fabric printing, painting, ceramics, bookmaking, 3D printing technologies and game development software. Key subjects of investigation include our complicity with corporate giants, the sculpting of online identities and the prescient qualities of dystopian science fiction. (instagram)

Read more: Petra Széman, isthisit?: Off Site Project (Instagram accounts)