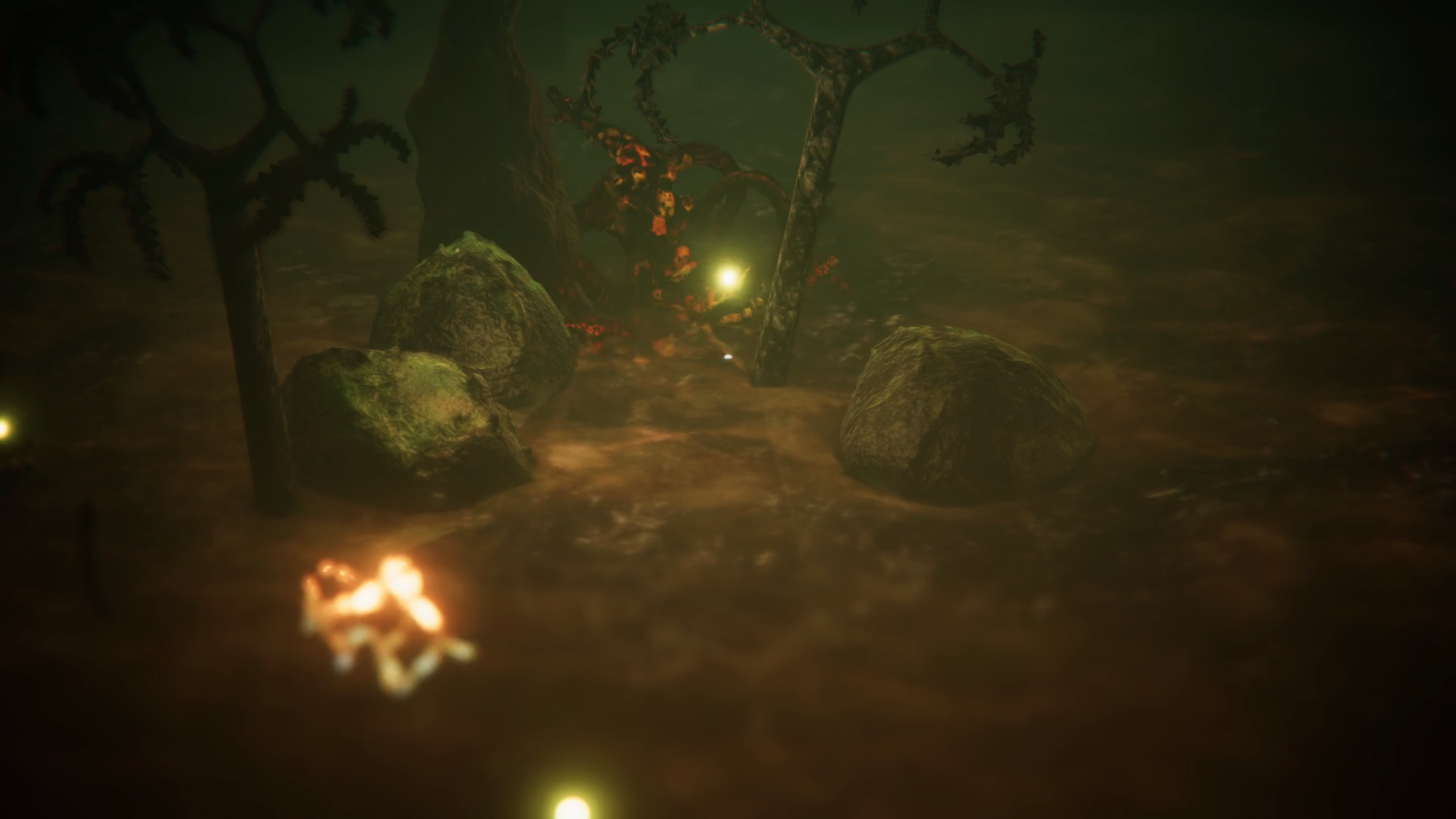

A screenshot from Piles (Hitman), a performance by Chris Kerich, 2018

There’s a powerful scene in Pablo Larrain’s Postmortem (2010), in which the protagonist Mario (Alfredo Castro), walks nonchalantly among piles of bodies. Mario is a transcription clerk in a hospital morgue that suddenly fills up due to an unforeseen event. Postmortem is set in September 1973, after the CIA-backed coup that culminated with the overthrowing of the democratically elected president Salvador Allende and the extermination of thousands of Chileans (Americans are generally cool with direct intervention in other countries’ internal affairs — elections included — as long as they are the perpetrators rather than the victims: this is why “9/11” means very different things to Chileans and Americans).

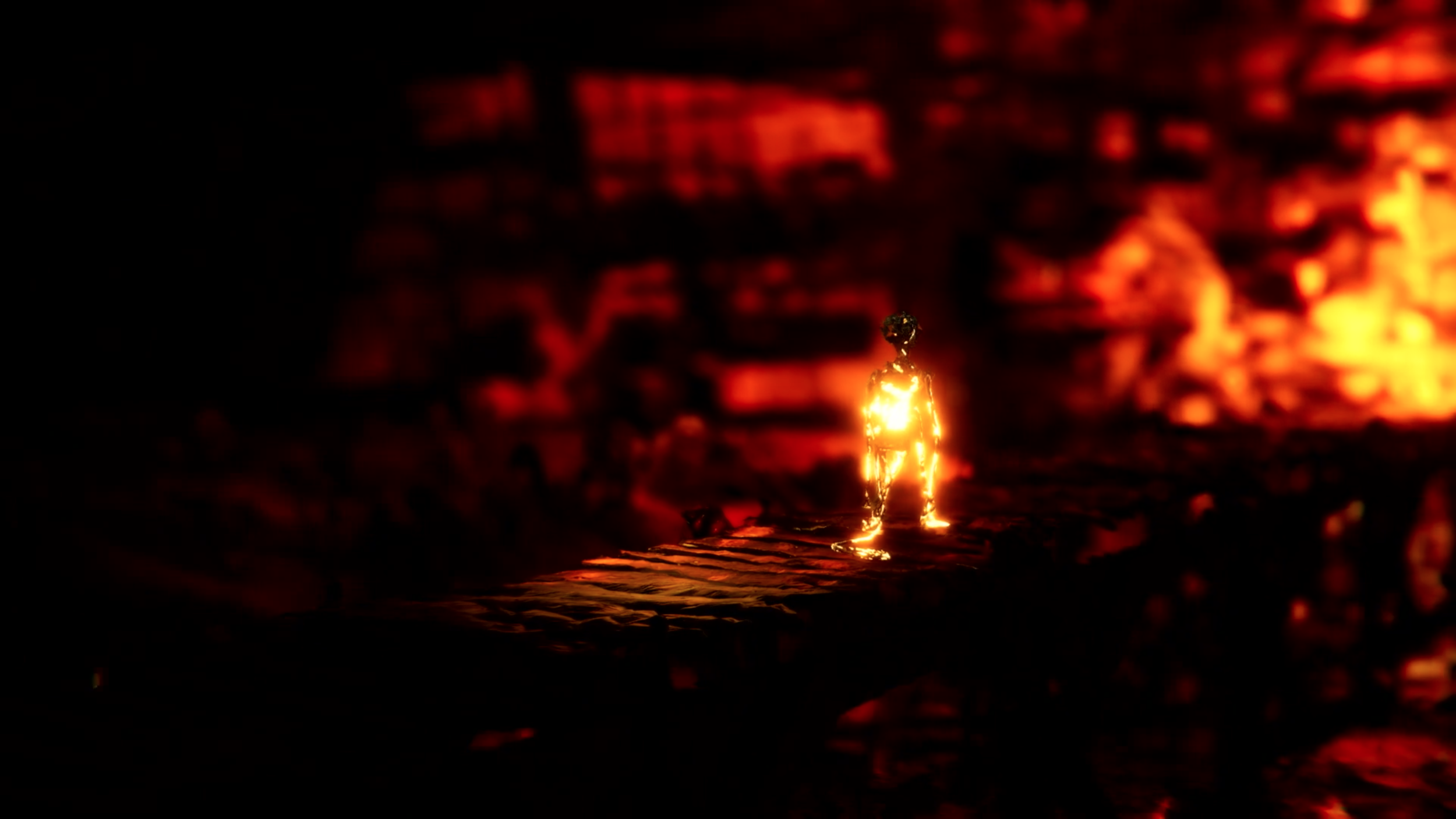

Chris Kerich’s Viscera Cleanup Detail (Piles) is featured in this year’s special screening series THE CLASSICAL ELEMENTS. Clocking at around eighty minutes, is the longest work at MMF MMXXI, but it’s only a portion of a larger body of work (no pun intended) entitled Piles (2018), “a collection of over 22 hours of video recordings, livestreamed on Twitch, of the piling up of dead or unconscious bodies in seven different video games: Dishonored: Death of the Outsider, Skyrim, Hitman, Metal Gear Solid V, Viscera Cleanup Detail, Slime Rancher, and Tabletop Simulator.” In a wide ranging video interview with Gemma Fantacci, Luca Miranda, and Riccardo Retez, the American artist currently enrolled in a PhD program at U.C. Santa Cruz discusses a project that spawned a variety of paratexts, including eight short critical essays on his website (here’s one on Dishonored, here’s another on Hitman). The pace of Piles is eclectic, ranging from the frantic to the slow and meditative (Hitman is a perfect example of “slow machinima”).

Viscera Cleanup Detail (2015) is a self-referential janitorial simulation game developed by RuneStorm. Players perform as a janitor tasked with cleaning up the gory aftermath of gunfights that have taken place in various science fiction environments. The goal is to remove bodies, corpses, limbs and organs left behind by unseen characters. However, the artist’s intention clashes with the game designers’ intended goals. As Kerich explains in his accompanying statement,

In this video I do anything but clean, and actually leave the level I have selected, “Evil Science”, even dirtier than it was to begin with. […] I only use the mop to try to dislodge a limb that is stuck under a table and otherwise just use the janitors’ ability to carry things to create the pile.

Piles is a multi-layered commentary on themes ranging from the ethics of game mechanics to the representation of death in digital spaces. “Like all the other bodies in this project, their mechanical function and infrastructural purpose defines their representation and their corporeality,” he concludes. If somebody were to stumble into one of his videos on the web — which would not be easy since they are unlisted on YouTube and “surrounded” by contextual, critical information on the artist’ website — they could hastily dismiss them as just another of the hundreds of prankish, juvenile videos currently hosted on YouTube (yes, body piling in video games is a “thing”). But unlike most of such vernacular videos, Piles has a strong political subtext. As Kerich explains,

The symbolic resonance of a pile of bodies in a game is political. The mechanics of how a pile of bodies is made in a game is political. The infrastructure governing how aesthetic representation maps to gameplay mechanics in a game is political. Who has access to power, and what kind, in a game is political. Who has the access and time to play a game is political. Watch closely, and take none of it for granted.

Both the invisible janitor of Viscera Cleanup Detail and the morgue clerk in Larrain’s Postmortem seem cogs in the machine: after all, piling up bodies or certifying their deaths is just a bureaucratic gesture, devoid of any meaning or consequence. They cannot undo what just happened nor they show any interest to. On one level, they are mere accomplices. On another, however, the obsessive repetition of their mortifying acts and the accumulation of inanimate objects elevate their task to the realm of performance art.

Chris Kerich is a programmer and artist living and working in Santa Cruz, California. He is interested in systems — and their breaking up —, constrained art, information, critical science studies, and video games. A candidate in the Doctorate program in Film and Digital Media Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, Chris received a Master of Arts from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in 2017 and a Bachelor of Science from Carnegie Mellon University in 2013. His works has been exhibited internationally including digital art retrospectives like the MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL (2019) and Vector Festival (2018), Toronto, Canada.

In una delle scene più memorabili di Postmortem (Pablo Larrain, 2010), il protagonista Mario (Alfredo Castro), cammina con nonchalance tra mucchi di corpi. Mario è un mero impiegato dell’obitorio di un ospedale che si riempie rapidamente dopo un evento inaspettato. Il suo lavoro consiste nel certificare che la morte delle vittime non è riconducibile al suicidio. Postmortem è ambientato nel settembre 1973, dopo il colpo di stato promosso dalla CIA che culminò con il rovesciamento del presidente democraticamente eletto Salvador Allende e lo sterminio di migliaia di cileni (gli americani non hanno alcun problema ad a intervenire direttamente nelle elezioni di altri paesi nella misura in cui non sono bersagli bensì mandanti dell’”interferenza”: il significato dell’“undici settembre” per i cileni e e per gli statunitensi non coincide).

Viscera Cleanup Detail (Piles) di Chris Kerich è inserito nel ciclo di proiezioni speciali THE CLASSICAL ELEMENTS. Grazie a una durata di circa ottanta minuti è l’opera più lunga tra quelle presentate all’MMF MMXXI. Tuttavia, rappresenta un semplice frammento di un ambizioso progetto intitolato Piles (2018), che consiste in “oltre 22 ore di registrazioni video, trasmesse in live streaming su Twitch dell’accumulo di corpi morti o incoscienti in sette diversi videogiochi: Dishonored: Death of the Outsider, Skyrim, Hitman, Metal Gear Solid V, Viscera Cleanup Detail, Slime Rancher e Tabletop Simulator”. In una video intervista con Gemma Fantacci, Luca Miranda e Riccardo Retez, l’artista americano e dottorando all’Università di Santa Cruz, in California ha discusso la concezione ed evoluzione di un progetto che ha generato una varietà di paratesti, tra cui otto brevi saggi critici pubblicati sul suo sito web. Il ritmo dei vari segmenti di Piles è eclettico e spazia dal frenetico al contemplativo (per esempio, il segmento dedicato a Hitman esemplifica in forma paragidmatica la nozione di “slow machinima”).

Viscera Cleanup Detail (2015) è un gioco di simulazione di pulizie autoreferenziale sviluppato da RuneStorm. Il giocatore assume i panni di un addetto alle pulizie incaricato di sanificare gli spazi in cui hanno avuto luogo sanguinosi scontri a fuoco. In altre parole, l’obiettivo non è sporcare di sangue il pavimento e le pareti, come in un tradizionale sparatutto in soggettiva, ma rimuovere le vittime: corpi, cadaveri, arti e organi. Tuttavia, l’intento dell’artista non coincide con gli obiettivi prefissati dai designer. Come spiega Kerich nel suo testo introduttivo, “In questo video lascio il livello che ho selezionato, Evil Science in uno stato ancora più lercio di quanto non fosse all'inizio. […] Uso il mocio solo per cercare di rimuovere un arto che è bloccato sotto un tavolo e altrimenti sfrutta l’abilità dei custodi nel trasportare oggetti per creare un mucchio di cadaveri”.

Piles è una penetrante riflessione su temi differenti, dall’etica delle meccaniche di gioco alla rappresentazione della morte negli spazi digitali. “Come tutti gli altri corpi che fanno capolino all’interno di questo progetto, la loro funzione meccanica e il loro scopo infrastrutturale definisce la loro rappresentazione e la loro corporeità”, conclude. Se qualcuno s’imbattesse nei video di Kerich online “per sbaglio” — il che non sarebbe facile dato che non sono esplicitamente visualizzati su YouTube e per di più sono “circondati” da informazioni critiche e contestuali — qualcuno potrebbe liquidarli come un esempio di tanti altri video buffi, bizzarri e comici attualmente ospitati su YouTube (la dpcumentazione audiovisiva dell’accumulo dei corpi nei videogiochi rappresenta un vero e proprio genere). Ma a differenza della maggior parte di queste produzioni vernacolari, Piles non fa mistero del proprio sottotesto politico.

Come spiega Kerich,

La risonanza simbolica di un mucchio di corpi in un videogioco è politica. La meccanica sottesa alla costruzione di una pila di corpi in un gioco è politica. L’infrastruttura che governa il modo in cui la rappresentazione estetica si associa alle meccaniche di un videogioco è politica. Chi ha accesso al potere, e di che tipo, all’interno di un videogioco è una questione politica. Chi ha accesso e tempo per videogiocare è una questione politica. Guarda attentamente e non dare nulla per scontato.

In apparenza, tanto il custode invisibile di Viscera Cleanup Detail quanto l’impiegato di Postmortem di Larrain paiono meri ingranaggi all’interno di una macchina mostruosa: l’accumulo dei corpi e la certificazione della loro morte sono un puro gesto burocratico, privo di qualsiasi significato o conseguenza. I due non possono annullare quanto è successo né manifestano alcun interesse a farlo. In un certo senso, sono complici del sistema. Ma è proprio la ripetizione dei loro atti mortificanti — che culmina con l’accumulo coatto di oggetti inanimati e la stesura di certificati di morte — a renderla indistinguibile dall’arte performativa.

Chris Kerich è un programmatore e artista che vive e lavora a Santa Cruz in California. Studia i sistemi — e la loro messa in crisi —, l’arte vincolata, l’informazione, i cultural studies e i videogiochi. Dottorando nel programma in Film & Digital Media presso l’University of California a Santa Cruz, Chris ha ottenuto un Master of Arts presso il Massachusetts Institute of Technology di Boston nel 2017 e una Laurea di Primo Livello presso l’Università Carnegie Mellon nel 2013. Le sue opere sono state presentate a livello internazionale. Ha partecipato a numerose rassegne di digital art, tra cui il MILAN MACHINIMA FESTIVAL (2019) e Vector Festival (2018) di Toronto, in Canada.