Following our recent exploration of Merlin Dutertre’s Lullaby (2019) – which is now accessible here after its VRAL show – we turn our focus to the works that have shaped his artistic vision. After examining Jon Rafman’s groundbreaking A Man Digging (2013), we now shift our lens to Jonathan Vinel’s avant-garde machinima, Notre amour est assez puissant (Our Love is Powerful Enough, 2014).

Dream PATREON-EXCLUSIVE CONTENT

〰️

Dream PATREON-EXCLUSIVE CONTENT 〰️

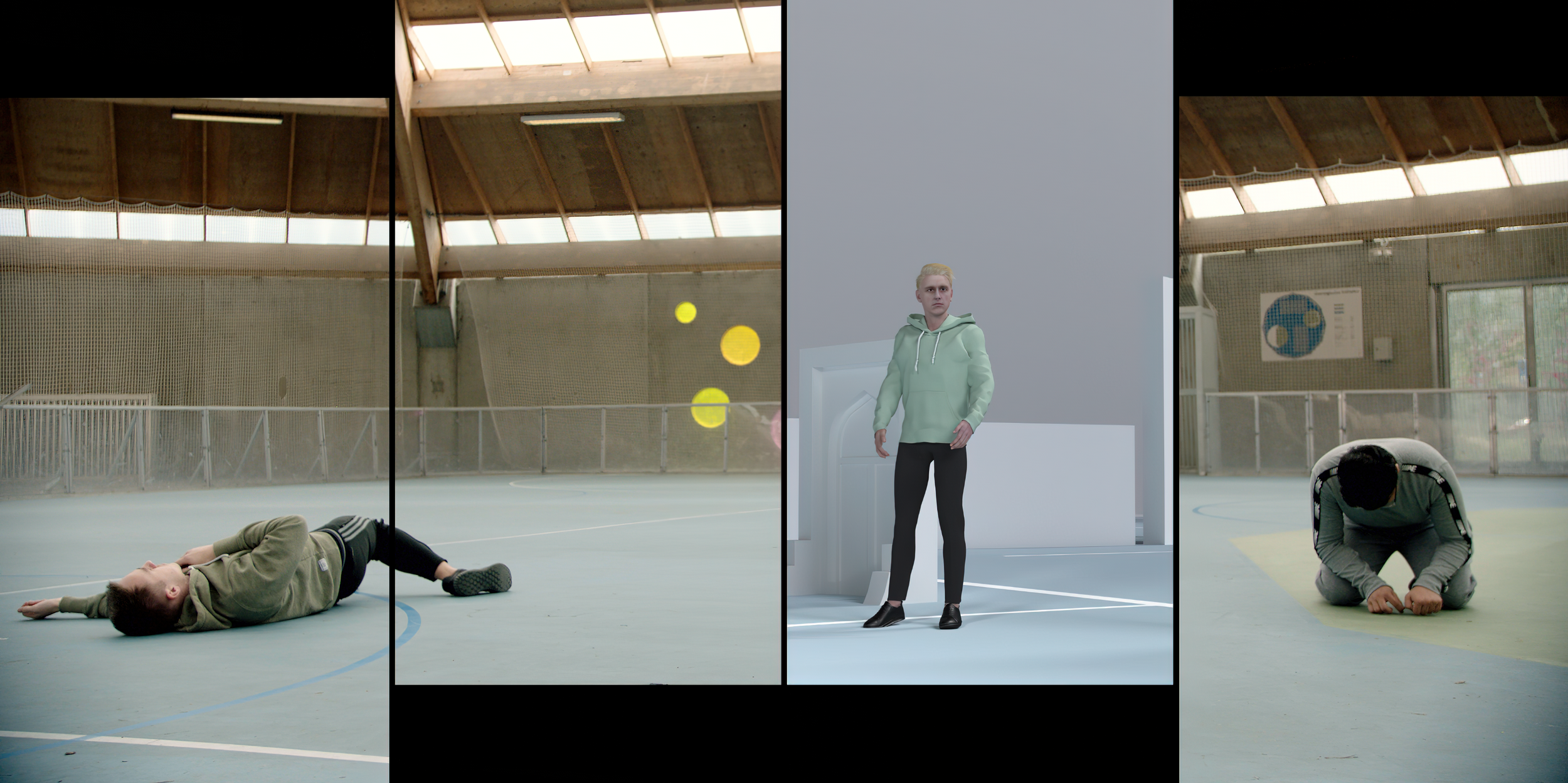

“In video games, you get to look at the environment in a way that you don’t in real life, because it’s beautiful and magical. But this leap into the game also allows you to live and experience things differently. In the end, it’s about reconnecting better through disconnecting.” (Caroline Poggi)

In an insightful interview, Dutertre attributes his formative years in the 2010s to YouTube, which he considers pivotal in shaping his identity as a filmmaker. Back then, Dutertre engaged enthusiastically with gaming-related content on the video sharing platform, although the concept of machinima initially eluded him. His high school years marked a turning point, ignited by the early works of Jon Rafman and Jonathan Vinel.

In this short essay, I will discuss Vinel’s machinima and then broaden the context to provide a clearer picture (no pun intended).

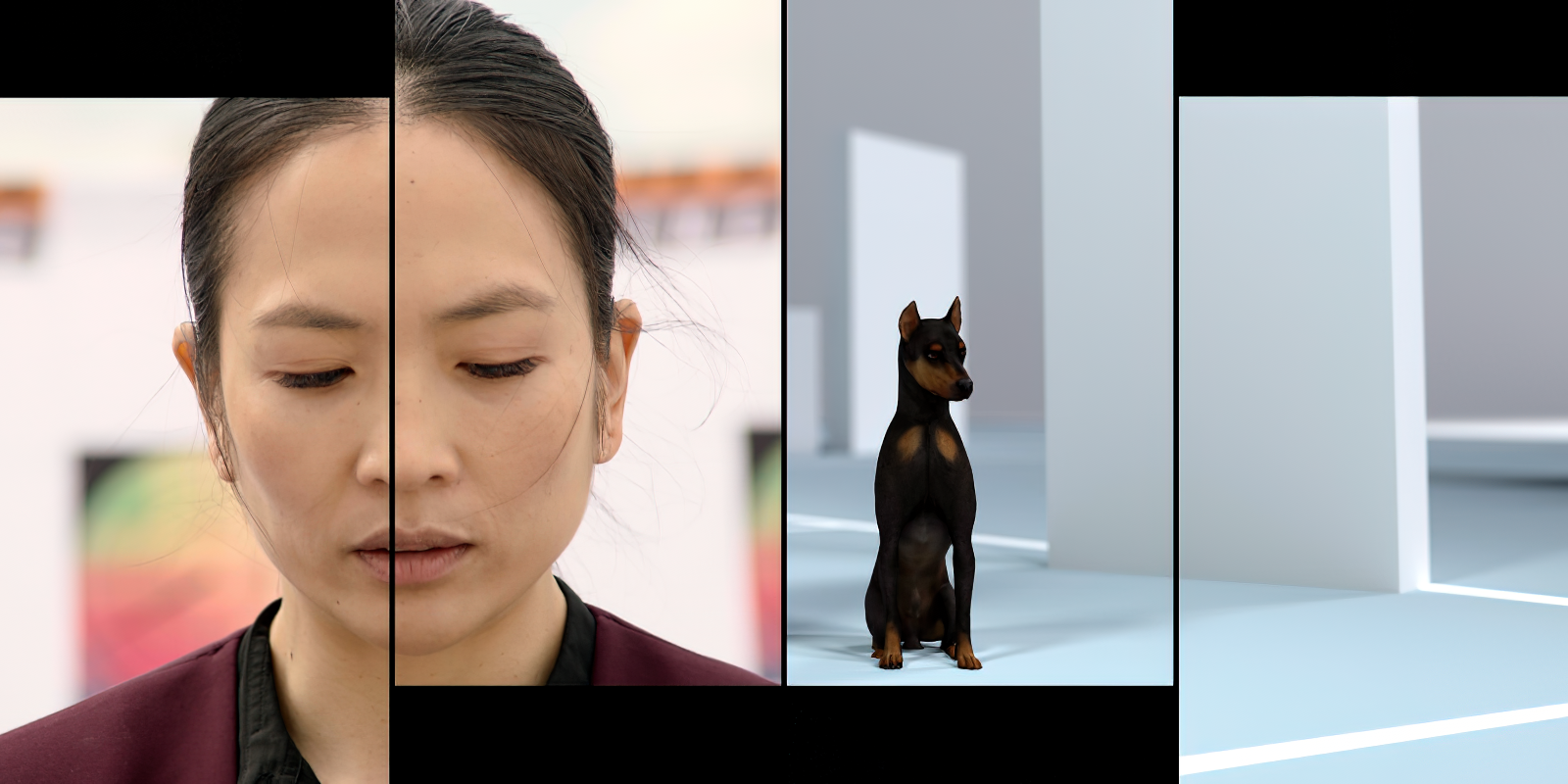

Born in 1988 in Toulouse, Jonathan Vinel studied editing at the esteemed film school La Fémis in Paris where he cultivated his passion for games, cinema, and pop culture. He later met Caroline Poggi, a Corsican native born in 1990. Poggi studied at Paris IV University and at the University in Corsica. The two crossed paths in college and directed several short films separately – including Poggi’s Chiens, and Vinel’s Notre amour est assez puissant. Their subsequent collaborative filmmaking practice comprises award-winning shorts, including the Golden Bear-winning Tant qu’il nous reste des fusils à pompe (As Long As Shotguns Remain) and Martin Pleure (Martin Cries, 2017), and full feature films, including Jessica Forever (2018), a paradigmatic example of what has been labeled the GAMECORE genre, which we will address in a separate post.

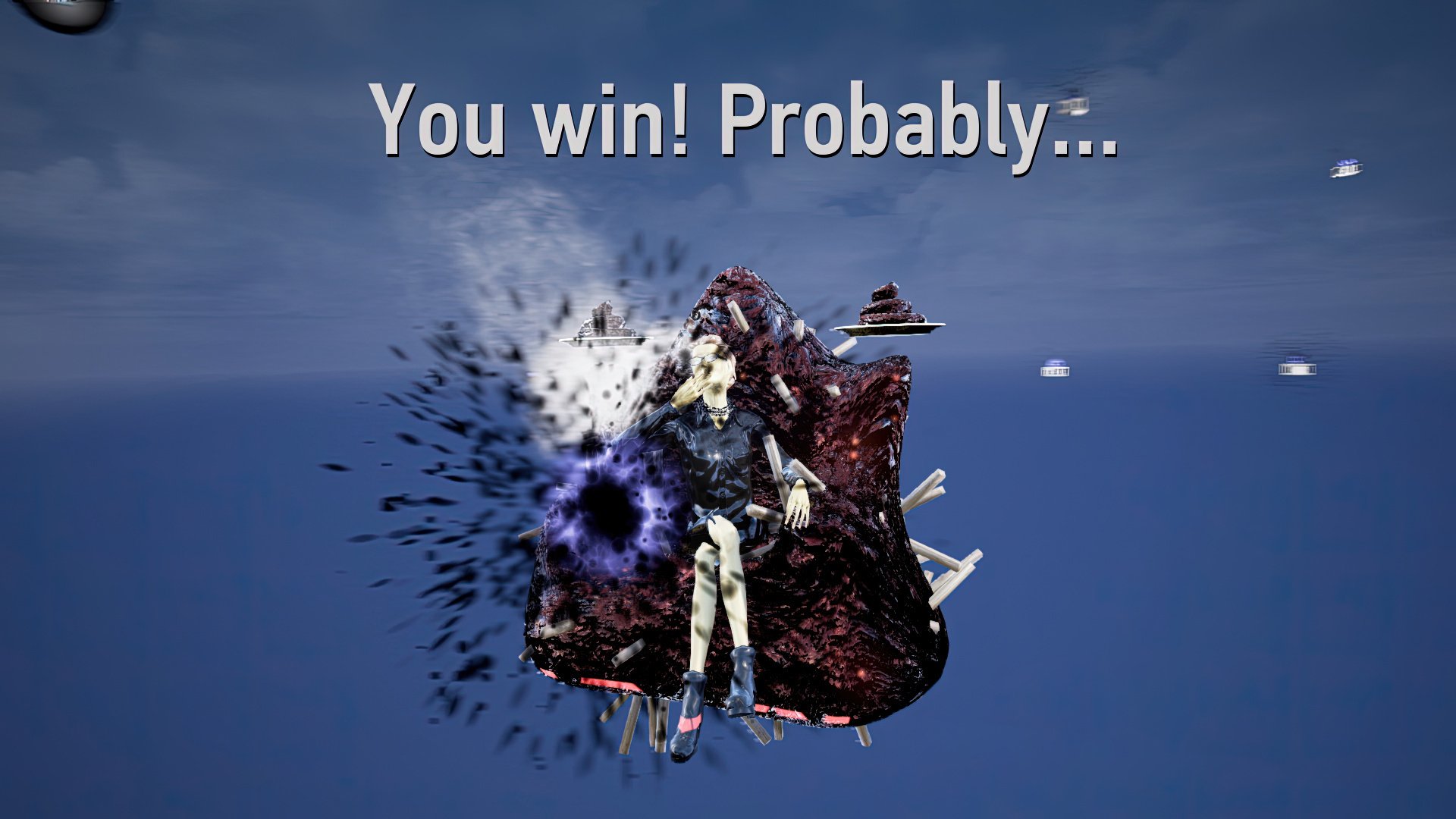

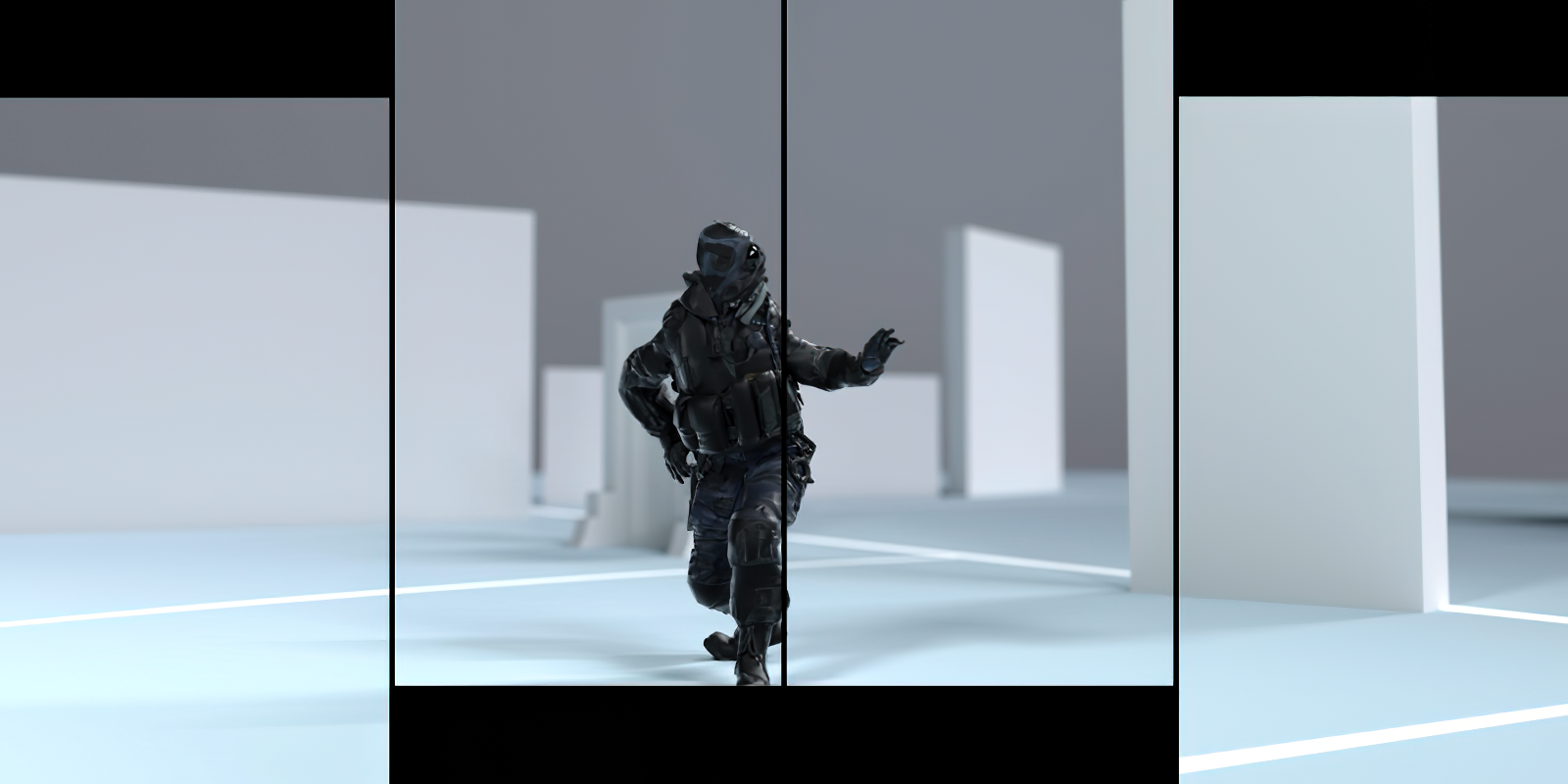

Vinel’s nine-minute machinima offers a complex interplay of disparate elements: militaristic imagery from first-person shooter games, romantic idealism, and metaphysical purity symbolized by a computer-generated tiger evocative of Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s surreal narratives.

Let’s unpack these three themes.

Firstly, Notre amour est assez puissant draws heavily from the visual and thematic elements found in first-person shooter games such as DOOM (id Software, 1993). These games are characterized by their aggressive, fast-paced action, and often hyper-violent scenarios. They usually involve a single protagonist navigating a hostile environment, armed with various weapons, and fighting off enemies in a dog-eat-dog world. The imagery is often dark, gritty, and designed to evoke a sense of urgency and danger. Vinel’s machinima comprises unsettling sequences set initially in a high school and later in a zoo, which evoke the disturbing prevalence of mass shootings in the United States. As for the latter, a group of virtual soldiers spend their evening slaughtering the trapped animals – elephants, monkeys, crocodiles – for “fun” and out of boredom. Both sequences are shocking: the calmness and slow pace which accompanies the narrator’s monotone speech heighten this sense of uneasiness…

Matteo Bittanti

Works cited

Brody Condon, Adam Killer, in-game performance, color, sound, video game mod, various lenghth, 1999, United States

Jon Rafman, A Man Digging, digital video, color, sound, 8’ 20’’, 2013, Canada

Jonathan Vinel, Notre amour est assez puissant, digital video, color, sound, 9’ 16”, 2014, France

This is a Patreon exclusive content. For full access consider joining our growing community.