PATREON-EXCLUSIVE CONTENT

〰️

PATREON-EXCLUSIVE CONTENT 〰️

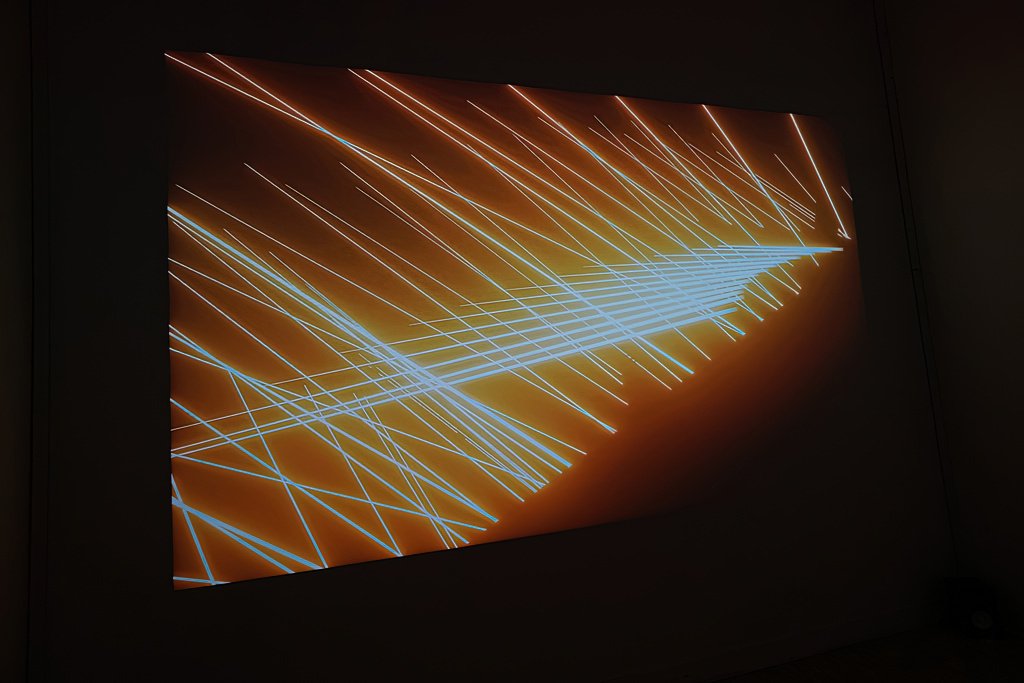

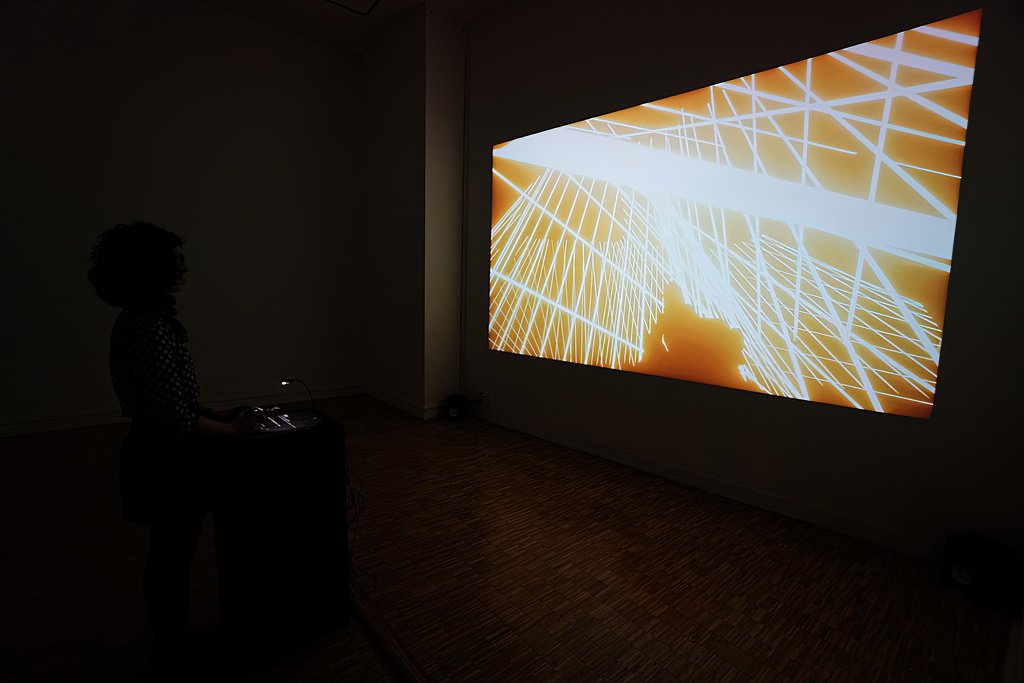

Currently on display at VRAL is Ghost City, Hugo Arcier’s groundbreaking 2016 video installation, which, until now, has never been exhibited online. After discussing 11 Executions and the Limbus series, we conclude our examination of Arcier’s game-based works with FPS (2016).

Alongside 11 Executions, FPS is one of Hugo Arcier’s most thought-provoking game-based installations. This interactive piece – which debuted in 2016 in the context of the Fantômes numériques exhibition at Plateforme Paris – is accompanied by a soundtrack by Stéphane Rives and Frédéric Nogray, also known as The Imaginary Soundscapes.

As most readers will likely know, FPS is the acronym of First-Person Shooter, a genre of video games that emerged in the United States at the beginning of the 1990s. Early examples include Wolfenstein 3D (1991) and Doom (1993) both developed by id Software, a company from Mesquite, Texas. For those who are unfamiliar with FPSs, suffice to say that these games are presented from the visual perspective of the avatar: the player views the game world as if through their character’s eyes. The primary gameplay element involves shooting and combat from this first-person perspective. Players must aim and shoot enemies and opponents using a variety of guns and weapons, which occupy the center of the screen. The pace and gameplay is fast, intense, and action-packed. FPS games tend to have a strong focus on reflexes and hand-eye coordination. The competitive element is a major component in most FPS games, which are known for immersive visual and audio experiences that make the player feel part of the world and action. Common elements include detailed graphics, surround sound, and realistic physics. In short, the FPS is a quintessentially USA-centric video game genre: the fact that a society that venerates weapons created an entire genre of techno-violence celebrating gun culture as a playful pastime makes perfect sense.

It should come as no surprise, then, that the FPS is also one of the most criticized genres of video games. They have been accused of promoting real life violence and aggression, usually by opportunistic, bi-partisan politicians funded by the weapon-industry, represented by the National Rifle Association. For instance, it is ironic that both Hillary Clinton and Donald Trump suggest the existence of a strong link between simulated violence and real life violence against all scientific evidence. Nonetheless, it is indisputable that the core mechanics of most FPS games involve shooting and killing, often in graphic ways. This has led to concerns that they are making violence seem mundane and potentially desensitizing players, perhaps an even more pernicious side effect than instigating aggression. Moreover, FPS games tend to prioritize action and combat over storytelling and character development. This had led some to criticize them as glorifying violence for its own sake. In terms of representation, many FPS games have been accused of promoting problematic stereotypes by depicting enemies from specific real-world groups, regions, or ethnicities. This kind of problematic representation also extends to women: female characters have often been underrepresented or depicted in sexualized ways in FPS games. The FPS has been accused of feeding hyper-masculine power fantasies. Moreover, some argue that the emphasis on the subjective view of the FPS is not purely visual, but ideological. For this reason, FPS games have been accused of promoting a limited perspective centered around the player character, rather than allowing for a diverse range of points of view. Additionally, the fast pace and visceral nature of FPS gameplay allows little time for empathy, reflection or consideration of consequences of violence. Their addictive qualities have also come under attack: FPS games are designed to keep players engaged, which has led to warnings about these games promoting addictive tendencies, especially in children. Finally, competitive online multiplayer FPS games are often plagued by aggressive behavior, bullying, and discrimination in chat/voice communications between players. The term “toxic” is usually cited in these debates. For these – and other – reasons, the FPS genre is considered…

Matteo Bittanti

This is a Patreon exclusive content. For full access consider joining our growing community.