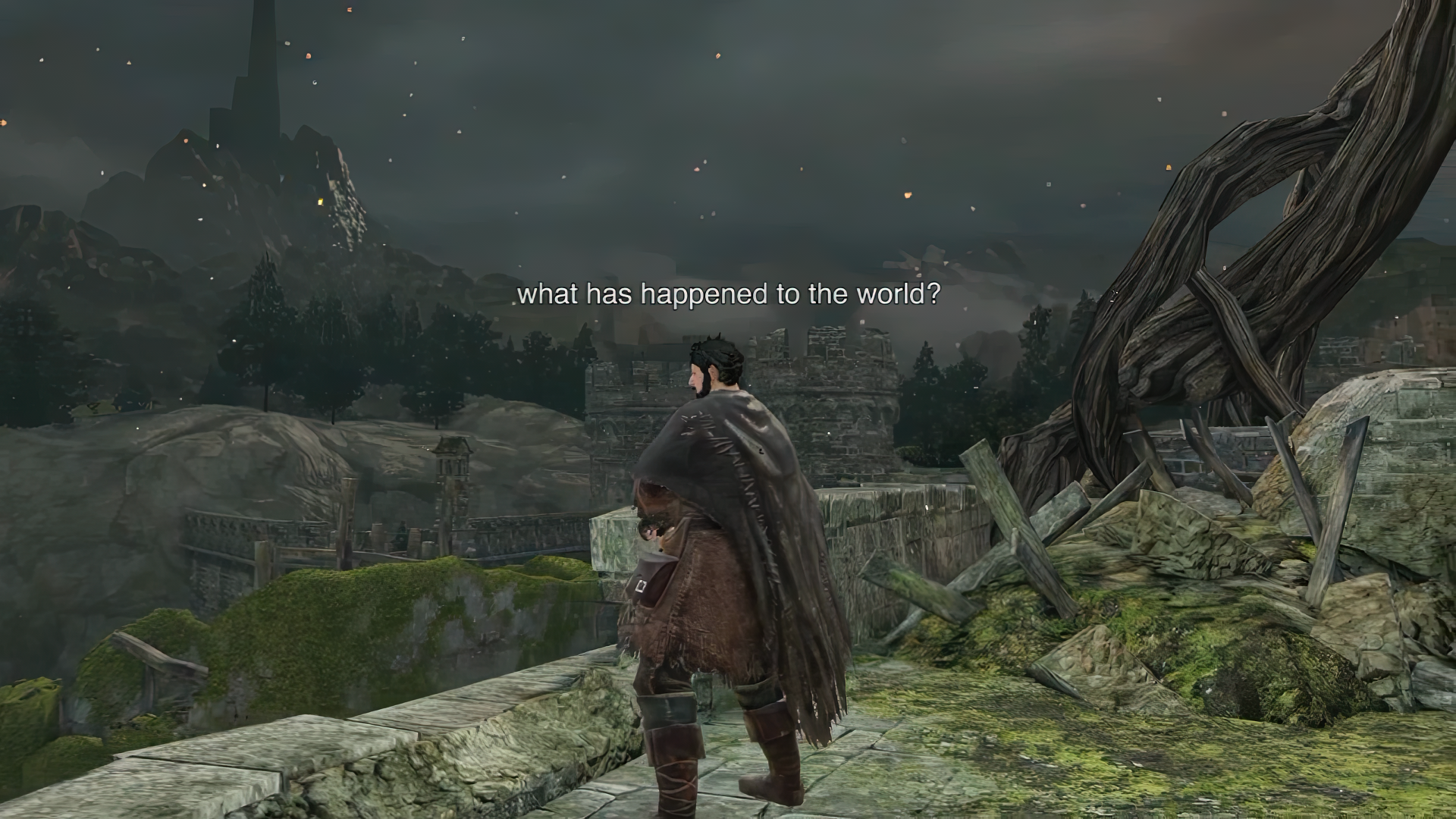

A hybrid of video essay, conceptual walkthrough, visual poem, and documentary, L’Autre Monster (The Other Monster) exemplifies the most experimental side of machinima. The French artist - who’s been working with video games for several years - uses Capcom’s Monster Hunter World (2018) to bring to the foreground the affective nature of playing, that it, the emotional, emphatic connections created by interaction design, and specifically, by the relationship between the player and her/his avatars, that is, alter egos and sidekicks. At the same time, Desaubliaux highlights the inner workings of the virtual world simulated in the game, flora and fauna. Specifically, she brings to the viewer’s attention the sheer contradictions between the pro-environmental message of the game and the reality of video game playing, as game-related technologies - including streaming - are extremely power hungry and thus their carbon footprint is far from negligible. It’s remarkable that the more we destroy the environment on a daily basis, the more we strive to reconstruct an idealized version of “nature” in video games and virtual worlds where there is no trash, litter, and microplastics. In a sense, we are replacing IRL nature with its simulation. We live in Philip K. Dick’s world.

The rationale is simple: economics. Virtual worlds are just products to be sold to the masses and there’s nothing that works better than a cute, smiling creature from across the screen to close the deal. Desaubliaux stresses that the appeal of these kinds of games is the liveness of the worlds they depict, their dynamics and their responsiveness. But she also emphasizes the artificially of such constructs with an insistent use of glitches throughout the video: a beetle breaks apart and a cascade of pixels take over the screen. A close up of branches and leaves show the highly geometric, polygonal-nature of this world. Still, the sunsets and sunrises are always perfect. Rivers and oceans are clean. Animals roam free instead of becoming either roadkill or fodder for industrial farming. Desaubliaux engages in critical play, to borrow Mary Flanagan’s expression. She is also an explorer (in Richard Bartle’s terms) and a documentary filmmaker.

She is also a geologist and an ethnographer. She uses the virtual camera to zoom in and out. Several sequences of her monumental documentary are reminiscent of the screensavers of AppleTV and of virtual aquariums: spectacular scenes shot by drones, up high in the sky so that the mess below is not visible, or simulations of microworlds, such as a fish tank in which entropic forces are kept at bay. She mentions the inherent tension between being a “tourist” in virtual worlds and a true resident, a “local”, which is how the game community perceives itself. It’s not just about aesthetics: to fully belong, one must be fluent in the language of the game and its creatures. One must be familiar with the lore, that is virtual folklore. She describes how players create this world by projecting their emotions onto the creatures that populate it, algorithms dressed up in fancy textures…

(continues)

Matteo Bittanti

Works cited

Alix Desaubliaux

L’Autre Monster (The Other Monster)

digital video/machinima (1920 x 1080), color, sound, 48’ 26”, 2021, France (in French with English subtitles)