We are delighted to share an interview with Ben Nicholson, the author of the tonic of battersea park which will be screened at the Interactive Museum of Cinema, Milan, Italy on March 25 2023 as part of the MMF MMXXIII in the program Neither Intelligent, Nor Artificial.

PATREON-EXCLUSIVE CONTENT

〰️

PATREON-EXCLUSIVE CONTENT 〰️

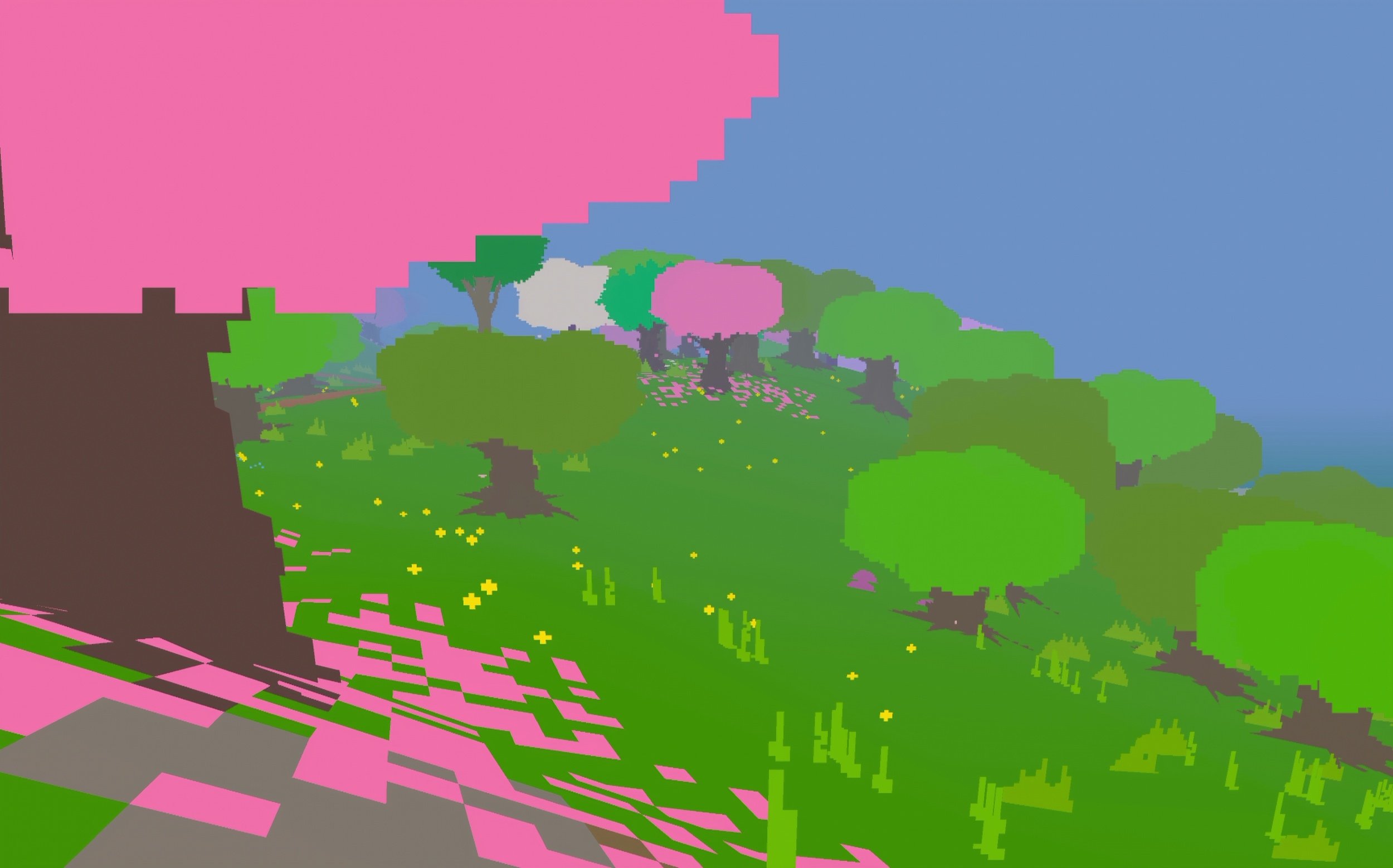

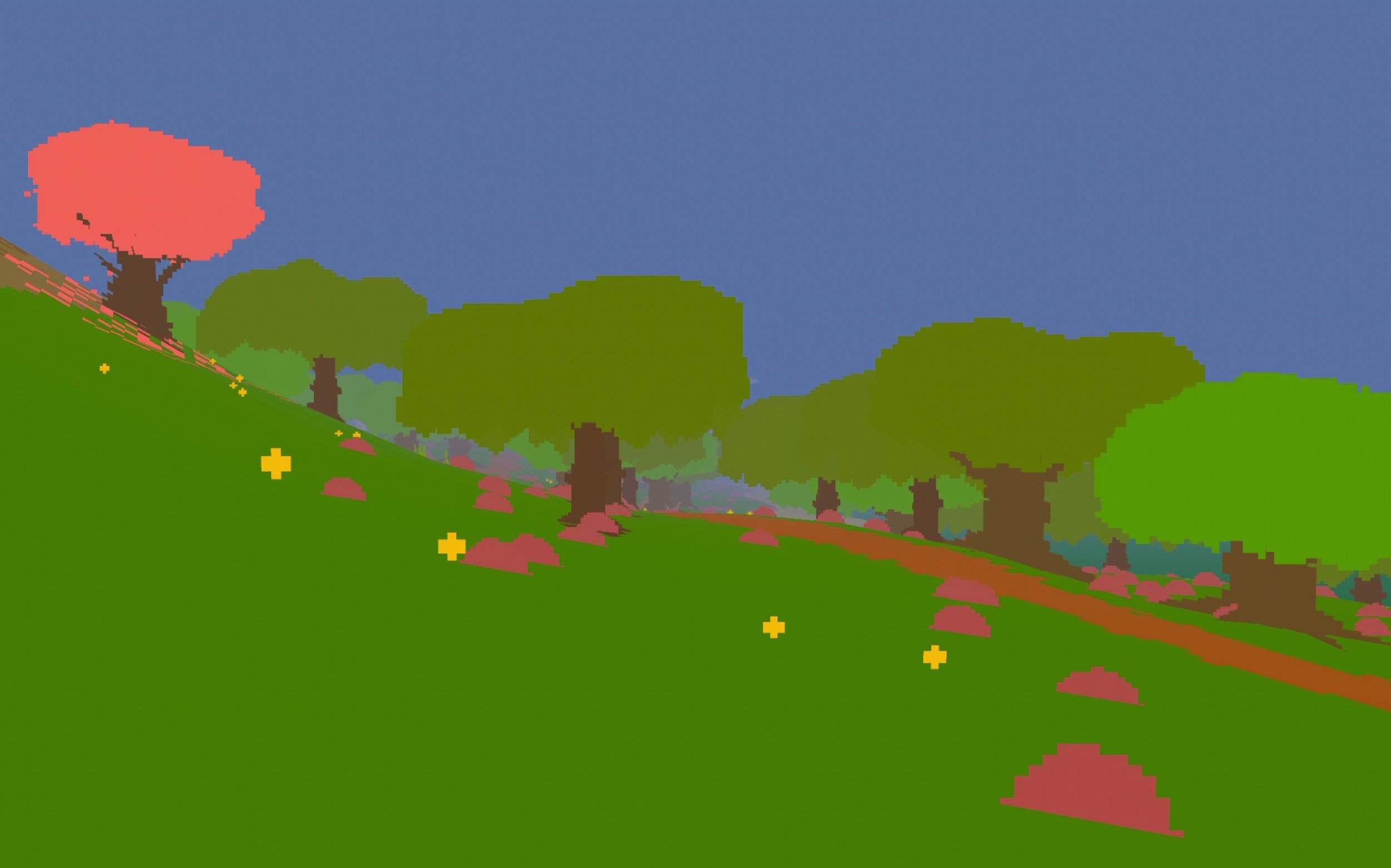

Ben Nicholson’s the tonic of battersea park is a poetic machinima that employs a procedural generated environment to evoke the constructed aura of “nature”. Using the video game Proteus and the writing of Henry David Thoreau, Nicholson creates a unique visual and auditory experience. At the heart of the machinima is the concept of domesticated nature. The appropriation of game’s procedural generated environment allows Nicholson to create a sense of lo-fi, pixellated beauty. The use of Thoreau’s words though the filter of ChatGPT adds another layer of depth (and irony) to this apparently simple machinima, imbuing it with an algorithmically generated quality. In the tradition of the avant-garde, the tonic of battersea parkchallenges traditional notions of art and pushes the boundaries of what is possible with machinima.

Ben Nicholson is a film writer, curator, and moderator. His writing has appeared in publications such as Sight & Sound, The Guardian, and Hyperallergic. Ben is the chief shorts reviewer for The Film Verdict and the founder of ALT/KINO, a project that showcases alternative voices and visions particularly in the realm of experimental film. He is also the artistic director of the Alpha Film Festival, which had its first edition in March 2023. Ben has curated programs for festivals such as Sheffield Doc/Fest and Open City Documentary Festival, and moderated events for the Barbican Centre, ICA, and more. He holds a Master of the Arts in Film and Screen Media from Birkbeck College and has served on juries at the Go Short Film Festival and the Arab Cinema Center’s Critics’ Awards.

Matteo Bittanti: In the realm of contemporary video art and experimental cinema, machinima has emerged as a distinctive genre that challenges traditional notions of filmic creation. Can you expound upon your interpretation of this genre, and where you locate its place within the audiovisual landscape? Additionally, I’d love to hear about your initial encounter with machinima, and how it has influenced your artistic practice.

Ben Nicholson: I think my first encounter with machinima came back in 2018. I don’t recall the precise piece of work I came across first, but I do recall going on voyage of discovery while researching a piece I was writing on smart cities, and I was thinking about digital renderings of landscapes. I was trying to pull together my thoughts on certain moments in Theo Anthony’s essay documentary Rat Film and was reading Michael Crowe’s An Attempt At Exhausting A Place in GTA Online. Somewhere in amongst that, a friend recommended Total Refusal’s Operation Jane Walk and Jonathan Vinel’s Martin Cries. I never looked back and, I think, Martin Cries remains the machinima I cherish the most.

How I locate it and how it has influenced me are perhaps a little more nebulous to define, but I’ll try. I think I am someone that has been fascinated for some time in the potential of the compilation film, the video essay or, more generally, artworks made using found materials. Some of my favourite filmmakers of recent times – Peggy Ahwesh, Stephen Broomer, Bill Morrison, Soda_Jerk, Jean-Gabriel Périot, Lewis Klahr, Catherine Grant – have excelled in appropriating and adapting to fascinating effect. For me, the machinima I adore tends to often feel like something of an extension of that kind of practice. It is perhaps a little more malleable than existing video footage, in certain circumstances, but there is a similar tension in the way these films draw out their own narratives and meanings through liberated imagery – often in a way that can feel challenging to, or radically at odds with, the material’s original purpose. There are many other examples where machinima allows for a glorious virtual sandbox, but the found footage element appeals most to me.

Works cited

Ben Nicholson

the tonic of battersea park

digital video/machinima, color, sound, 2’ 37”, 2023, England

Made with Proteus (Ed Key, David Kanaga, 2013) and ChatGPT (OpenAI, 2022

This is a Patreon exclusive article. To access the full content consider joining our Patreon community.