Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal

Single-channel video (color, sound, narrator: Mamusu Kallon), 14’ 19”, 2023, Palestine

Created by Firas Shehadeh

Originally commissioned by Singapore Art Museum

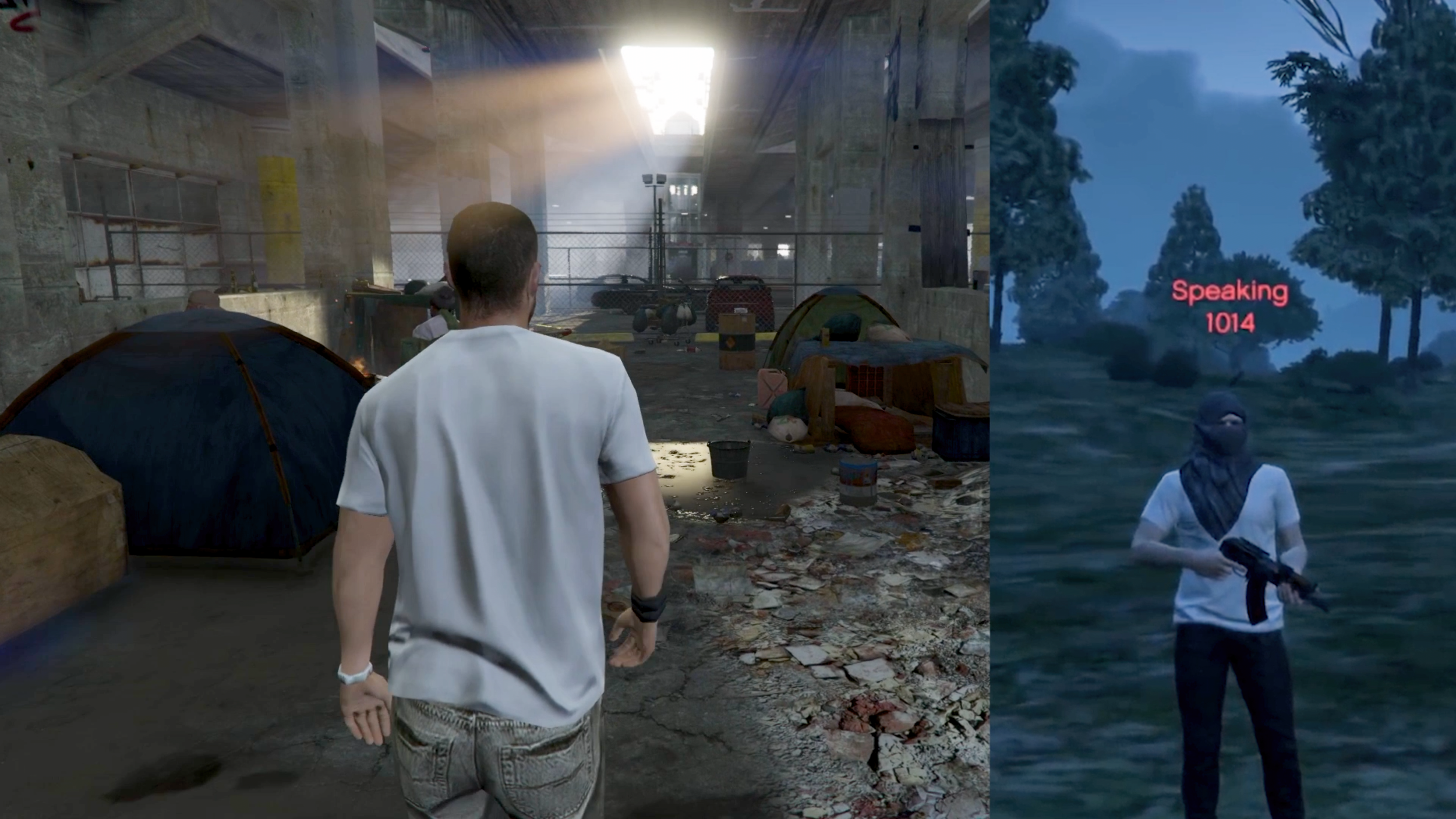

Part of Shehadeh’s ongoing research into video games and Palestinian youth culture, Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal combines found-footage of Twitch streamers and custom game mods for Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013). Unpacking video game mods as a form of contemporary archive — and therefore digitizing historic and contemporary architectural sites in addition to seemingly ubiquitous objects — the artwork proposes Los Santos, a virtual replica of Los Angeles, as the biblical “land of milk and honey”.

Firas Shehadeh is a Palestinian artist and researcher exploring issues of identity, meaning, and aesthetics in the digital age. Currently based in Vienna, his interdisciplinary practice engages with post-colonial effects, technology, and history through the lens of worldbuilding and internet culture. Shehadeh holds a Master of Fine Arts from the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna, where he is currently a PhD candidate. His education also includes studies in conceptual art, video, and architecture in Vienna, Barcelona, and Amman. Investigating topics like colonial legacies, memory, and belonging, Shehadeh creates speculative narratives that reveal unseen structures and realities. His research-focused practice utilizes and subverts the visual languages of new media, examining how technology transforms society’s relationship with knowledge and power. His work, which has been exhibited internationally, offers a critical perspective on the role of the internet and digital imaging in shaping contemporary identities, histories, and ways of world-making.

Matteo Bittanti: Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal is part of your ongoing exploration of video games, as well as social media, memes, and viral content, in relation to the Palestinian condition. I would like to start our conversation by asking if you could describe your own relationship to the medium of the video game in general and with Grand Theft Auto V in particular. How did the open world format — or any other specific feature of Rockstar Games’s popular title — inspired you to create a project related to the themes of displacement, violence, and belonging, among others?

Firas Shehadeh: My relationship with video games started in the early 1990s with Super Nintendo (SNES) in Saudi Arabia, east side close to Kuwait, where my parents were migrant workers. This was during a rough time for my family as it coincided with the Gulf War, a new U.S. Marine military base was established nearby. Additionally, this area was a center of oil production. Due to these circumstances among others, my parents got for me and my sister a Super Nintendo console, as we couldn’t really go outside. If we would go outside it would be mainly visiting other migrant families, from Sudan, Lebanon, and Egypt. This was great, to exchange game cartridges and do small tournaments.

While we played, our parents would sit in the background discussing various topics such as work, politics, the First Intifada, the U.S. attack on Al-Shifa pharmaceutical factory in Khartoum, the sanctions on Iraq… The SNES was eventually replaced by the Sega Genesis, and later on, I managed to get my own PC.

Having a personal computer was a revolutionary moment for me. At the age of 11, I was not so interested to participate in outdoor activities like playing football, but I was deeply interested in video games, computers, and the internet. In 1999, my math teacher at the United Nations school (UNRWA) in Al Nasir Palestinian refugee camp in Amman introduced me and four other selected students to HTML programming. We started by writing simple algorithms on paper and had weekly access to the computer room to apply our codes and learn new programs. This computer was the only one shared between the girls and boys schools. Things progressed real fast back then, thinking about it right now, I got a copy of Grand Theft Auto 2 in the same year, and I was hooked. This world was —and still is— fascinating.

GTA II was not only my introduction to the world of GTA but also how this world would progress later on. In this game, I started having new experiences I didn’t have before with Super Mario, Sonic The Hedgehog, or Streets of Rage. There were other games during that time, but GTA II was different. Coming back from school to this, was an escape that turned with time into going back to the world I am more familiar with somehow. I had a cheat sheet.

The year 2001 had a significant impact on my gaming journey. The Second intifada was just starting after the Israeli colonial forces killed 12-year-old Muhammad al-Durrah, the U.S. launched a brutal war on the Middle East. On the other hand, GTA III was released. This game set new standards for open-world and role-playing games. It was followed by GTA: Vice City and GTA: San Andreas.

I remember the first time I discovered what mods are, I bought a copy of GTA from downtown Amman: San Andreas Arab edition. The mod was developed by a Palestinian refugee in Syria, I think.

This integration of a world I loved with the world I lived in was truly fascinating. The mod included elements such as cars, music, and street banners that felt relatable. I even remember seeing a poster of Yasser Arafat in Grove Street. The game was already funny, chaotic, violent, and relatable. The first non-white protagonist in the GTA universe, the ghetto looked like a refugee camp. Palestinian and other non-white players felt represented with a cool, true, real character. Modders took it even a step further by bridging San Andreas and Palestine worlds.

Matteo Bittanti: In your early work Guerrilla 8-bit (2013), you creatively appropriated the vintage aesthetics of early video games to explore parallels between the rise of militant organizations like the Palestinian Black September Organization (BSO) and emerging digital technologies in the early 1970s. I found your use of the primitive 8-bit visuals quite striking, seeming to symbolize how rudimentary technologies can become powerful tools when harnessed for political aims, even as entertainment forms are usually dismissed as a trivial, puerile pursuit. I also found the juxtaposition between playful lo-fi aesthetics — pixel art portraits, chipmusic etc. — and the BSO quite provocative, in lieu of the latter’s activities. Am I correct in reading the work as suggesting that escapist media like video games can take on expanded significance and purposes when embraced by marginalized groups? Does this work also hint at connections across resistance movements and digital advancement in the 1970s era? After all, the computer revolution was sold to the masses as a direct continuation of the freedom and emancipation movements of the 1960s, as Fred Turner cogently explained in his monumental From Counterculture to Cyberculture (2010). Specifically, I interpreted Guerrilla 8-bit as drawing an evocative link between the emergence of Palestinian militants and the underlying technologies that enabled early gaming. Is such a reading accurate?

Firas Shehadeh: Radical imagination is rooted in reality. It is the ability to envision and create alternative narratives and possibilities within the constraints of our current world. In the context of the Palestinian resistance movement, radical imagination played a crucial role in shaping their struggle for liberation.

Video games, often seen as a form of escapism, can also be a means of engagement and empowerment. They have the potential to create immersive experiences that allow players to explore different perspectives and realities. In the case of the Palestinian resistance, video games can serve as a medium for raising awareness and educating people about their struggles.

Creating a spectacle has historically been a strategy employed by Palestinian resistance organizations since the 1960s. By embracing the image of resilience and strength, they aimed to counter the narrative of the helpless victims under ethnic cleansing and genocide that they had endured during and since the Nakba in 1948. This image served as a mirror for the Palestinians, showcasing their determination to exist, liberate and return to their motherland. The Palestinian who went through hell and came back standing in front of the world declaring “I exist and I will return.” This image was both presenting a reality and a spectacle. Palestinian anti-colonial acceleration brought with it, at the speed of light, hijacked airplanes, airports, AKs, cars, media and cameras – an image that was hard to unsee for the first time. The Palestinians were seen, not by the goodwill of the world, but by force. Existing in and outside of millions of TV’s and radio stations around the globe. The Black September Organization was one of the main generators that made that image. In Brother Malcolm X’s words, “We declare our right on this earth to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being in this society, on this earth, on this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.”

Guerrilla 8-bit reflects on the parallel between 8-bit computer processors and the Palestinian liberation movement. Both revolutionized computation, political organization, and media. Yes, you are right, media and technology can take on expanded significance and purposes when embraced by marginalized groups. It’s also a progression following the 1960s emancipation movements, there were the Algerian and Vietnamese anti-colonial movements, the Black Panthers, the student movement, and labor unions, etc. Those movements understood the power of communication media. They managed to hijack technology to deliver their word to the world.

In conclusion, radical imagination is a powerful force that allows us to envision and create a different reality. The Palestinian resistance movement, along with other marginalized groups, has harnessed the power of media and technology to amplify their voices and challenge the status quo. By doing so, they have demonstrated their existence, strength, and determination to reclaim their rights and land.

Matteo Bittanti: Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal makes an extensive use of mods. There is a long tradition in game-based art of deploying modding as a tactic — to borrow Michel de Certeau’s term — to hijack the meaning and ideology of such cultural artifacts as video games, and to subvert or reshape their narratives. How did you engage with the practice of modding to create Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal? Were there any particular technical or creative challenges you had to overcome? How does the modding of GTA help create meaning in relation to belonging and statelessness? How do you see this project fitting into the aforementioned tradition of artistic game modding?

Firas Shehadeh: As I mentioned, my engagement with game mods goes back to ripped copies of GTA San Andreas. Before that, there were not that many options for representation in video games. Those modes came at a time when computers and PC gaming were more popular, accessible, and cheaper. During that time, the world was also witnessing significant geopolitical events such as the Second Intifada, the U.S. invasion of Iraq, and the Abu Ghraib scandal. These events, coupled with the constant exposure to distressing images of dead Arab and Afghan children on television, further fueled the desire for representation. Mods were in a way an engagement with our images on screens, where young Arab players claim power and agency over their bodies.

In Marxist terms, these mods provided an alternative to the market logic that thrives on extraction, exploitation and competition. By engaging in modding, we were able to reclaim our creative potential and challenge the alienation imposed by capitalist systems. It was a way of hijacking meaning and ideology by taking control of the inaccessible technology and subverting the dominant narratives. Mods somehow – and maybe accidentally – brought a meaning by modifying GTA worldbuilding.

To hijack meaning and ideology by taking over inaccessible technology is not a new phenomenon. It was always a tool used by the colonized and the working class to overcome colonial and capitalist systems of control. One example is the PFLP OPEC siege, which quite literally did this in 1975 in Vienna. Led by Venezuelan revolutionary Carlos the Jackal, one of the demands was that the Austrian authorities broadcast a communiqué about the Palestinian cause on national media platforms gave voice to Palestinian refugees, on Austrian radio and television networks every two hours. This was maybe the first time that a Palestinian voice was heard on a European or Western mainstream network from the perspective of Palestinian refugees since the British colonization of Palestine.

Modding as practice, is very similar and fits within the same sampling, hacking, remix, reappropriation culture, and arts. It is a practice that subverts dominant narratives, encourages critical thinking, and empowers individuals to fulfill their creative potential outside the confines of market logic.

Matteo Bittanti: In Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal, you explicitly reference Clint Hocking’s notion of ludonarrative dissonance, which refers to disconnect between a video game’s narrative context and its gameplay mechanics. In short, ludonarrative dissonance occurs when the story a game “tells” and its interactive gameplay experience clash, diverge considerably or openly contradict each other. At the same time, I was wondering if you are familiar with another notion, that is “social realism” in games, which was introduced by Alexander Galloway in 2006. The latter refers to how well a video game simulates the social systems and conditions of the real world through its mechanics and dynamics. Galloway was interested in understanding how a game models societal behaviors, relationships, and structures in a realistic way. The more accurately a game reflects actual social dynamics and consequences, the higher its social realism. Galloway argues most mainstream games provide only low to moderate social realism as they offer abstracted versions of social systems that don’t capture real-world complexities. Within the same essay, he introduces the notion of the “congruence requirement” in relation to the theme of realism. He says:

I suggest there must be some kind of congruence, some type of fidelity of context that transliterates itself from the social reality of the gamer, through one’s thumbs, into the game environment and back again. This is what I call the “congruence requirement” and it is necessary for achieving realism in gaming.

He subsequently examines two independent video games, Under Ash (2001) and Special Force (2003), which provide a Palestinian perspective in contrast to American military games like America’s Army and satisfy the aforementioned congruence requirement. He argues that Under Ash takes a more sobering, documentary-like tone than Special Force depicting the Palestinian struggle and hardships under occupation. Under Ash provides an alternative for Palestinian youth to play from their own perspective while Special Force feels more like a role reversal of American games with Israelis as bad guys. Under Ash creators wanted to design a game Palestinian players can relate to based on their daily struggles. Special Force seems more focused on turning the tables ideologically through a vehemently anti-Israeli narrative.

After this long preamble, I would like to ask: based on your experience, is modding practiced as a counter-strategy to the shallowness and simplification of mainstream games in portraying the dynamics of real social systems and issues? Does it fulfill Galloway’s notion of “congruence requirement”? Or is modding a political tool only if it is supplemented by a specific kind of gameplay?

Firas Shehadeh: I am not sure about achieving reality in video games, as players have many reasons to immerse in a game. It could be for entertainment, escaping social, political, or economic reality, education, or research to name a few. The hyperreality of video games is what makes them appealing, as they provide new ways for interaction and interpretation. However, it is important to acknowledge that video games are ultimately a fictional creation, even when they serve functional purposes, as what late Harun Farocki calls “Operational Image.”

This visualization of data, whether in a U.S. high-tech military base or a mod developed in a refugee camp, both try to achieve a reality in a non-real setting. One works to create a system that abstracts life for domination, the other works on giving meaning to life. But at the end of the day, those two forces will meet on the ground, and one of them will beat the game.

Under Ash and Special Force were released during the Second Intifada in 2001, and the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003 respectively. The second edition of both games came in 2005 (the liberation of the Gaza Strip) and in 2007 (following the Israeli war on Lebanon). As you can see, the timing in which both games were released was connected to real-life politics on the ground. The message of Under Ash 2 was placed on its cover: “What you will see is not an illusion... it is the truth. A human epic that we place as a trust in your hands so that you do not forget... your land and your roots.” This explains why Under Ash aimed to have an educational purpose, while Special Force engaged players in an ideological battleground, similar to games like Call of Duty and Battlefield, but from the native’s perspective.

I don’t think Grand Theft Auto is a shallow game per se, or delivers a shallow experience to the player, despite how much critique it gets. Generally speaking, all cultural artifacts signify a meaning and a political position whether we can relate to it or not. They convey knowledge and information, and as Edward Said argues, in the West it serves power for domination. On the other hand, it represents for the natives and the working class the power to abolish the “West” (colonialism and capitalism).

Concepts such as “Ludonarrative dissonance” by Clint Hocking, “social realism” by Alexander Galloway, and “Serious Game/Applied Game” are essential to exploring the potential and aesthetics of video games. Games like Under Ash and Special Force played a vital role in the development of the Arab world’s video game development, considering their context and the limitations of the early 2000s technologies. Remember, this was also still during the time before social media platforms and the fast internet, at a time of transition from Web 1.0 to 2.0, memes were still in the early days. Besides the fact that, unlike Call of Duty and Battlefield, Under Ash and Special Force were created with small budgets and teams, with Under Ash possibly being developed solely by one person, Radwan Kasmiya.

Modding, the act of modifying games, provides players with the opportunity to be the main character in a more profound way. In the real world, players from colonized nations may never have the chance to fulfill the role of the main character, as they are often subalterns. Their struggle lies in becoming the master, the main character, and in-game decisions and team configurations often reflect their real-life experiences and perspectives.

Matteo Bittanti: I am intrigued by your creative use of an uneven, asymmetric split screen in Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal. The juxtaposition of one square and one horizontal frame allows two distinct narratives to unfold in parallel. This stylistic choice stands out to me compared to most split screen videos that cut the image into matching windows. Sjors Ritgers’ Polarized Interactions comes to mind. I’m curious what inspired this more unconventional approach? What effect were you hoping to achieve by showing mismatched perspectives simultaneously? What significance does the form of the split itself hold in relation to the work’s themes?

Firas Shehadeh: Thanks Matteo for your insightful analysis. As I was working on finalizing the script, researching footage, and gameplay, I was thinking of how entertainment and design elements have infiltrated videos in the art context. Standardization of video works (Adorno), the same tested formula for mass appeal. In recent years, there has been a tendency towards overediting, overcoloring, and using loud music to grab attention, whether intentionally or unintentionally. However, I decided to take a completely different approach. I wanted the viewers to have the time to process the information conveyed in my work, in a more slow environment. This contradicted the nature of the materials and game in my case study, both in terms of theme and speed, which made it even more exciting for me to break the tempo and composition. I used an asymmetric split screen and created conflicts in tempo between the narration and gameplay to draw attention to the narration and images by highlighting these inherent conflicts. My focus is on aesthetics rather than design.

In Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal, I incorporated three different aspect ratios, varying tempo in the voice-over, a soundscape of Los Santos, and sounds from both gameplays and Palestine. I wanted to explore the contrast between tranquility and speed, capturing the essence of real-time experiences.

Split-screen technique, although one of the oldest special effects in cinema, still holds its power. It allows for the juxtaposition of separate actions within the same frame, effectively emphasizing the relationship between images, image-making, and viewing.

Matteo Bittanti: In the accompanying text to Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal, you imply the existence of a dichotomy between the so-called Developed World — often labeled as “First World” — and the Global South in relation to what Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer called the Culture Industry. Specifically, the Global South is conceived as the raw material, a set of resources, used by the former to entertain privileged audiences via formulaic, homogeneous, highly commodified content. You suggest that the Global South serves as a source of inspiration and setting for the worldbuilding and game mechanics of mainstream video games. Interestingly, Grand Theft Auto has been accused by such scholars as David Leonard of providing cheap thrills for a mostly white, often affluent, audience who’s mainly after “ghetto tourism”. Throughout a variety of penetrating essays, he argues that the Grand Theft Auto series relies on and perpetuates negative stereotypes about black characters and urban communities, depicting predominantly African American neighborhoods as violent criminal spaces lacking in moral complexity. According to Leonard, the series indulges in problematic assumptions that glamorize “gangster” lifestyles and link blackness to danger and deviance. He critiqued the games’ single-dimensional portrayals that recycle racist ideologies in popular culture’s depictions of urban communities of color. I wonder if the dichotomy that you describe is not merely geographical — i.e., First World vs. Global South —, but also pertains to socio-economic disparities within national contexts. Does this suggest that certain groups — regardless of national context, are treated as “exotic” resources because of their signifiers of Otherness, language, appearance, and mannerisms — are mined by game developers that are essentially ransacking them as content to fill their expansive virtual worlds? In other words, do you see marginalized populations everywhere facing this kind of commodified exploitation in video games?

Firas Shehadeh: Short answer, yes. Marginalized populations everywhere are a target for commodified images in all entertainment. Cultural tourism is one primary notion for this exploitation. GTA V has been criticized for its exploitation of marginalized populations in entertainment, specifically through the concept of cultural tourism. However, the game's complexity and evolving nature have allowed it to transcend mere exploitation. It offers critiques on capitalism, gentrification, social media, and the society of the spectacle, while also providing irony and cynicism. The participation of players as developers has further contributed to the game's multilayered complexity.

I don’t wanna find excuses for GTA V. While acknowledging the game’s problems, I genuinely enjoyed it… And it feels as if the developers apologized and “fixed” those problems in Red Dead Redemption 2. Its nihilistic story finds the solution in its “good ending” of the game, Deathwish. The success of the game lies in its liberation from norms, real-world consequences, and the social contract, granting players agency and the opportunity to explore truth, as Adorno calls it, “Truth Content.”

It is worth noting that many critiques of GTA V overlook a significant turning point brought by the character Tanisha, who confronts Franklin with reality towards the end of the game. This adds depth to the narrative and challenges the players’ perception of the game world.

Going back to Adorno’s “Truth Content”, GTA V offers a chance to experience an extreme version of “America” and its themes of liberty, guns, capitalism, and violence. It provides critique without imposing a specific political statement or ideology, instead allowing players to discover truth throughout the gameplay.

Having said that, Western cultural depiction of the Third World, the colonized, minorities, working class, and marginalized communities in general, tends to exploit the world of those communities and extract enjoyment, by and for further escalating its domination over the exploited. Here, the subject of domination is denied what Said calls the “Permission to Narrate”, in which the “society being studied is an object rather than a subject of history. It can be described by others, but cannot describe itself.” The exploited community can be located geographically, but not as a simple West/East, North/South, as orientalists like this oversimplification of dualism – as in Samuel P. Huntington’s The Clash of Civilizations, which influenced war criminal George W. Bush –, and many fall in this trap too.

If we describe globalization as a process of westernization, “the globalization of the false was also the falsification of the globe” (Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, 1988, p. 10). In Short, yes, marginalized populations everywhere face this kind of commodified exploitation – not only in video games but in any piece of the cultural industry. This exploitation aims to produce cultural goods used to manipulate society. (Here, I think, GTA V managed to break this standardization of culture and arts, by breaking societal values and norms.)

Matteo Bittanti: You refer to Los Santos as a metaphorical “land of milk and honey” for Palestinians — a biblical phrase evoking a promised land of prosperity and abundance. In your work, this seems to suggest Los Santos represents an idealized virtual homeland, especially when contrasted with the hardship of displacement experienced in reality. The theme of religion and notion of the sacred is expressed at titular level. Los Santos, the city of Saints, is astutely connected to the Holy Land. I’m curious if you intend to draw a parallel between this fictional place of abundance within the game and the concept of an imagined or hoped-for Palestinian state. If so, does this point to the difficulty of achieving such a homeland in the real world, whereas the video game format allows it to exist representationally? In other words, are you suggesting that these virtual spaces can provide a gratifying experience for Palestinian players that remains forever elusive in their daily lives? Or, via Theodor Adorno — whom you explicitly mention — games have an inherent didactic function compatible with the ideological positioning of the producers, making all games an explicit or implicit form of propaganda?

Firas Shehadeh: The Land of Milk and Honey is not really metaphorical, to be honest. This was literally my family’s work in Palestine before European colonists killed the cows and destroyed the apiaries during the Nakba. I brought the contrast between the Land of Milk and Honey as both, the biblical image and my family’s real life and work in contrast to Los Santos’s Liberty and Guns on one hand and the reality of European settler colonialism in Palestine on the other. I am using this contrast to describe a Double-Vision of examining the reality and illusion in Palestine and in Los Santos. The biblical metaphor here is brought for satire and irony. I understand how the West relates to the metaphor of the Land of Milk and Honey, but I also lived, learned, and experienced what actually Palestinian peasants go through against the Western colonial killing machine. Again, the people of the land of milk and honey never had the chance to narrate themselves. My grandparents were telling me how honey is the pride of my village. By applying double-vision reading on the city of Saints/Los Santos, again you see the same contrast between what is holy and what is evil. Here, Palestinian mods of Los Santos are bringing it in full circle.

In historical terms, Grand Theft Auto is what Americana and its globalized dream stand for in our current time, whereas Red Dead Redemption is bringing a story of the struggle against Americana before this model was “declared” victorious. The violence of GTA is a byproduct of what Americana (in the U.S. and in “Israel”) stands for in reality. The player’s in-game violence is a reaction to that. They are the product and the victim of this violence. The game gives a chance to the player to engage and/or escape the reality of a colonial context, to an RPG open-world game that can be literally bigger than blockaded Gaza Strip (since 2005) or a refugee camp.

Similar to the history of hip-hop, and the constant false accusation of violence, it’s connected to a specific race, class, and culture. Hip-hop went through a journey of accusations, capitalist domestication (like in ghetto tourism), and resistance to that by the innovation of new sub-genres. In recent years, we saw this with Drill music and the criminalization of hip-hop artists and video games together in France, in reaction to the riots sparked by the French police killing of Algerian Moroccan Nahel Merzouk in June 2023, who was 17 years old. Nahel, like many of his generation growing up in apartheid France, was a gamer and part of the hip-hop culture in his neighborhood. Yet, Emmanuel Macron kept repeating the “Values of the Republic,” a white supremacist value system, to the rioters. State-organized violence is order, and the oppressed people’s reaction to that is violence.

Matteo Bittanti: Thank you for the thoughtful explanation. I apologize for my naïveté in asking an insensitive question. Your tactful response has prompted me to reflect further. If I may, I have another query based on our discussion. You put forward the idea that gamers, developers, streamers, and hackers from the Global South have modified commercial video games to construct their own hyperrealities, rehearsing life under colonial rule. Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal explores the fictional city of Los Santos as a parallel space to the Palestinian experience and, in doing so, examines how customized gaming environments allow marginalized communities to roleplay localized struggles of resistance, subjugation, and survival. Palestinian interventions in the simulated world of GTA mirror the broader push to assert cultural belonging and narrative control within an inherently asymmetric power structure. I am very interested in the practice of roleplay, which refers to players creating unique storylines and characters within the open world environment produced by a video game company, in this case, Rockstar Games. To roleplay means to interact in-character with others on a players’ managed server to collaboratively improvise ongoing narratives and relationships. Servers feature custom game modes that support the roleplay experience, like jobs, activities, realism mods, etc. tailored to the chosen theme. This practice has an enormous potential for expanding, or even rewriting, the political dimension of make believe. Going back to my previous question, is the modded version of GTA an effective space of liberation or just another expression of confinement? A golden cage where players can experience the thrill of freedom? Virtual freedom through a game surrogate may have psychological value for players. However, it lacks tangible impact on material conditions of oppression and, as such, it provides a limited form of liberation. Can we perhaps compare roleplaying GTA to what Hakim Bey has called a TAZ, a temporary autonomous zone? In a sense, the modded gameplay carves out ephemeral pockets of freedom and control amidst confinement, so it can function like a fleeting autonomous zone. However, unlike an effective TAZ, the liberty in-game is bound by dependence on the overall platform, which is itself fragile and precarious: a cease-and-desist letter by well paid lawyers hired by Rockstar Games can crush any attempt at hijacking GTA. Unsurprisingly, “fighting piracy in the Global South” has traditionally been used as a form of colonial and imperialist strategy. In short, I wonder if modded gameplay could be seen as a conditional, imperfect form of liberation: psychologically freeing as it may provide catharsis, but materially, structurally, and perhaps even ideologically still confined. More of a release valve than true emancipation, perhaps. Is the intent of an artistic intervention “simply” to suggest a horizon of possibilities? To allude to “alternative geographies” in lieu of a constricting reality”? To imagine the end of capitalism using tools created by capitalism?

Firas Shehadeh: Modders, at least in the Grand Theft Auto world, are presenting an agency over their worlds.

It’s very interesting you brought up Hakim Bey, an anarchist and poet. I almost believe that Rockstar games writers are at least inspired by him, somehow. He is like a Rockstar game in one person, both, Hakim and Rockstar, are white, problematic, radical, poetic, and nihilist, they explore the “other” culture in contrast to America, and their criticism of the empire, modernism, and capitalism, sometimes falls in reproducing racist tropes while trying to do good. Besides major concepts such as Hakim Bey’s “Pirate Utopia” and Dutch van der Linde’s “Savage Utopia,” Rockstar’s GTA and Hakim’s Temporary Autonomous Zone, the only difference is that Hakim was an anarchist who lived by his beliefs, Rockstar is a corporation that wants to make money. I mention this not to discredit Hakim’s TAZ or Rockstar’s GTA influence on popular culture but more to situate their work, the appropriation was reappropriated in a transgressive manner. The company is in a constant fight with GTA multiplayer modders. But we have to be aware that not all modders would deliver good, as not all would deliver bad either.

Generally speaking, the game was rigged from the start, and in Audre Lorde’s words, “for the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.” The genuine change would come in a real-life clash with the master outside the game. This is more or less my approach towards digital means: to use those tools with caution, without romanticizing whatever is hyped online for social change, and to ultimately be aware that social change will always happen in real life struggle by minorities, the working class, immigrants, and the colonized.

Role-playing localized struggles within games can provide players with a platform for rehearsal, imagination, and entertainment. Palestinian modders, for example, utilize game modification to reimagine their own experiences and to overcome the limitations of developing a game with limited resources. In contrast, the Israeli colonial military develops games from scratch. They don’t need to mod a game. In 2005 they literally built a game in the real world, in collaboration with the U.S. Army, for military training, they did construct a fake city called “Baladia”, which means a city or neighborhood in Arabic. It cost 45 million dollars and was built on colonized Palestinian land in 1948 by East European colonists. Baladia is a training center for military urban combat. It imitates a “Middle Eastern-style city.” Baladia was designed to train various military organizations, including the U.S. Army and UN “peacekeepers”. You see, Europeans have Baladia, Palestinians have Los Santos. Colonists with machine guns, natives with controllers.

Matteo Bittanti: Baladia reminds me of Sierra Pettengill’s Riotsville, USA. As you suggest, there’s a strong connection between simulations IRL and video games. Both are forms of mass control through different means, usually violence, virtual or enacted against civilians. I wanted to ask you about a different kind of role play. You explicitly reference Augusto Boal’s practice of “spect-actor” participation in theater as a means of collectively examining and addressing social issues. Given this connection, I’m interested in your perspective on the parallels between Boal’s theater and the participatory nature of online multiplayer games. Specifically, I’m curious if you see multiplayer game spaces as a new form of theater wherein players become active agents influencing the game’s unfolding narrative? Like Boal’s theater, multiplayer games promote intervention in the dramatic action and collective problem-solving: in the former, spect-actors may stop scenes, replace actors, improvise dialogue, or collectively explore alternatives that challenge power imbalances. Likewise, players are actively engaged in shaping, or even rejecting, a predefined narrative. In that sense, could multiplayer games provide a compelling contemporary platform for Boal’s vision of participatory theater as transformative social change? As active players or performers creating an “online community”, might game participants similarly find empowerment or liberation through these virtual theaters, as long as the game servers are managed by the players themselves rather than by corporations? I find it remarkable that, in 2015, Rockstar Games banned users with affiliations to the FiveM servers and, eight years later, the company acquired the same team of “rebels”: co-opt and conquer. These are clearly Games of Empire, as Greig de Peuter and Nick Dyer-Witheford described them.

Firas Shehadeh: Exactly, I agree with your thoughts on Boal’s vision of participatory theater and its connection with online RPG platforms. It is fascinating to witness how the combination of the GTA V online platform and modders has created a space for a unique blend of theater and gameplay. I came across streams, where Palestinian players literally engaged in Theater of the Oppressed without knowledge of it. They were able to perform scenes, establish rules, and engage in improvised dialogue, effectively reenacting their experiences of colonial violence. Some of these reenactments were traumatic, while others were hilarious, but they all ultimately conveyed a sense of pain, particularly when one begins to understand the underlying political impotence.

Matteo Bittanti: I’m very intrigued by the idea of the re-enactment via GTA. I would like to begin by underlining that the title of your, Rehearsal, has several meanings. In the performing arts, rehearsal is the repetitive process of training and perfecting a performance prior to presenting it publicly. It also provides a safer space for taking creative risks, problem-solving, and mastery of material through repetition. Finally, such experience is meant to evaluate and enhance performance in service of a live event. Around the seventh minute, the narrator mentions an apparent paradox: although GTA offers endless possibilities of identity play, reinvention, and transformation, roleplayers often re-enact their daily experience. They stage a careful reproduction of an event or situation they experienced within the confines of the simulation and then share their clips on social media with the hashtag @GTAreallife. Is this practice motivated by the fact that the simulation offers the very possibility of an alternative outcome, that is, a way for the players to “correct” and “amend” a perceived injustice?

Firas Shehadeh: In the game, the player is the main character, not collateral damage, not a number on a news outlet. The game is centered around the main character and the player behind it. The player’s story is the most important for the game to function. Rehearsing in the game means playing without risk in order to deliver a better performance. However, in the GTA Palestinian mod magic city, the outcome is predetermined on the streets. The gamification of death becomes a way to live, highlighting the brutal nature of the Zionist settler colonial rule in Palestine. This form of colonialism constantly erases the native world, giving Zionist settlers necropower over native Palestine and Palestinians. In the game, Palestinian gamers, despite everything, imagine a different outcome: full decolonization of Palestine.

Like An Event In A Dream Dreamt By Another — Rehearsal

Single-channel video (color, sound, narrator: Mamusu Kallon), 14’ 19”, 2023, Palestine

Created by Firas Shehadeh, 2023

Courtesy of Firas Shehadeh, 2023

Originally commissioned by Singapore Art Museum

Made with/in Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013)