SJORS RIGTERS

GAME VIDEO ESSAY

MARCH 21-27 2022/21-27 MARZO 2022 (ONLINE)

Introduced by Matteo Bittanti

POLARIZED INTERACTIONS

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 7’ 21”, 2021, The Netherlands

Polarized Interactions si appropria di Grand Theft Auto V per mettere in scena specifiche situazioni. Sfruttando spazi fotorealistici che simulano una grande varietà di interazioni, l’artista crea scenari in cui il giocatore interagisce passivamente con personaggi non giocabili (NPC). Mettendo in scena la relazione tra momenti di attività e inattività all’interno del gioco, Polarized Interactions invita lo spettatore a riflettere sull’esperienza virtuale e sul modo in cui essa condiziona il comportamento del giocatore IRL.

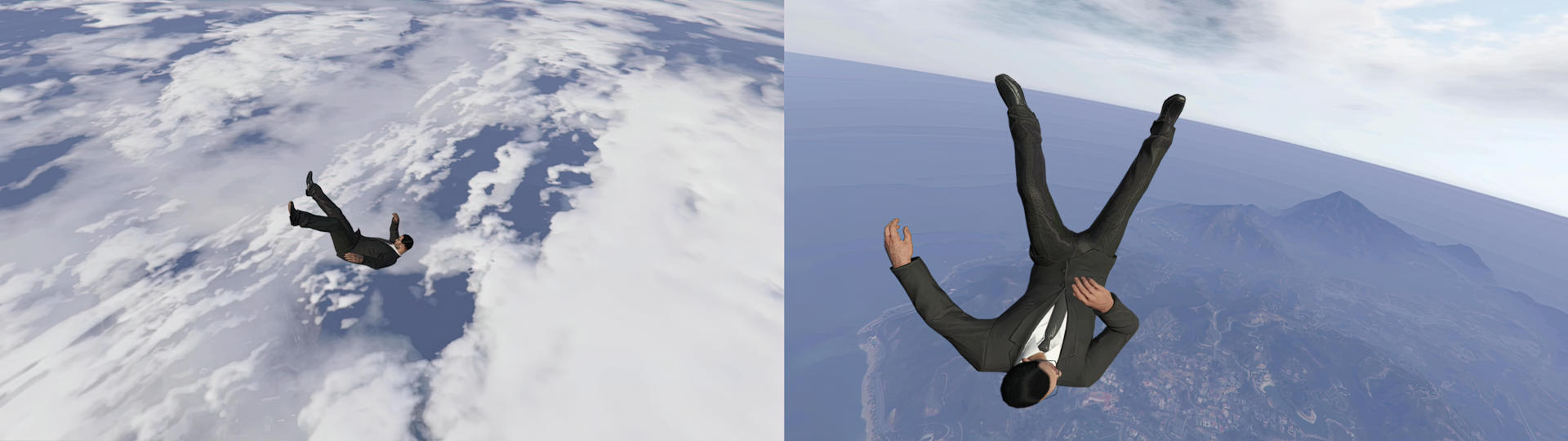

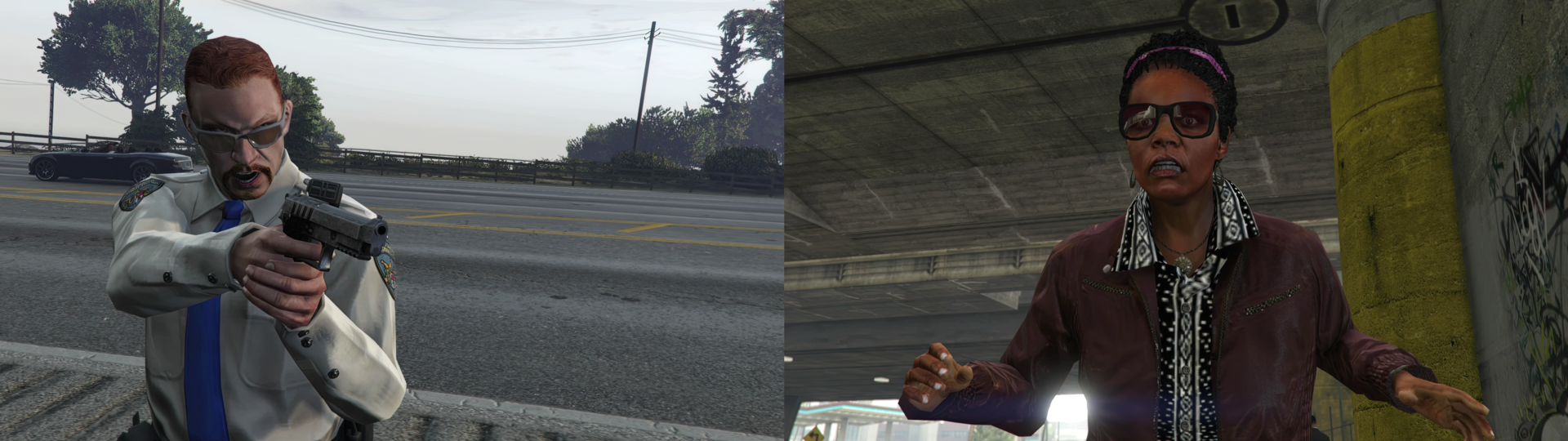

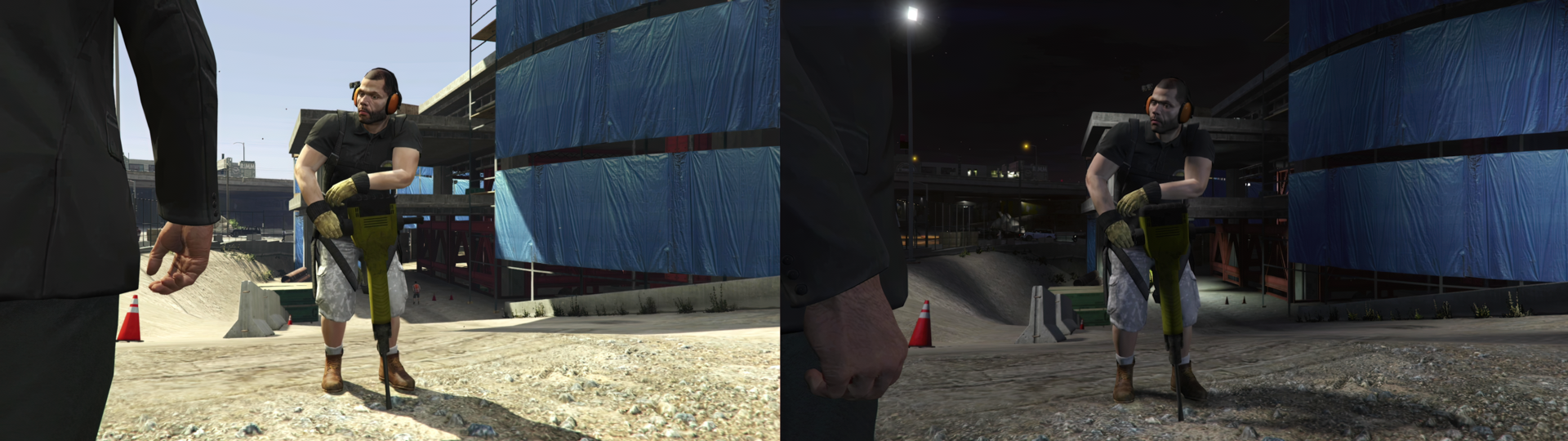

Polarized Interactions is a short machinima that appropriates Grand Theft Auto V to stage and test specific scenarios. By using a photo realistic open world that simulates an array of interactions, the artist creates situations in which the player passively interacts with non-playable characters (NPCs) in the game. By emphasizing the relationship between moments of activity and inactivity within the game, Polarized Interactions invites the viewer to consider the virtual experience and its influence on the player’s behavior IRL.

L’ARTISTA

THE ARTIST

Sjors Rigters (1995) è un graphic designer specializzato in visual identity e design editoriale. Dopo aver conseguito una laurea in Design presso la Royal Academy of Art dell’Aia, ha aperto il suo studio. Polarized Interactions è stato sviluppato come progetto inerente alla sua tesi sull’ideologia nei mondi videoludici. Sjors vive e lavora a Rotterdam, nei Paesi Bassi.

Sjors Rigters (b. 1995) is a graphic designer specializing in visual identity and editorial design. After graduating in Design at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague, he opened his own studio. Polarized Interactions was developed as a follow up to his dissertation focusing on the ideologies embedded in game worlds. Sjors lives and works in Rotterdam, The Netherlands.

INTERVIEW

Matteo Bittanti: Can you introduce yourself and describe your practice as a designer?

Sjors Rigters: I’m a graphic designer specializing in visual identity and editorial design. But I often describe myself as a visualizer or as an artist. I am interested in the field of communication and I tend to identify the core narratives of each issue I tackle, so that I can create the most appropriate and effective output, such as a publication or a video work, including machinima.

Matteo Bittanti: What is your relationship to video games and game culture? At the beginning of Polarized Interactions you mention that do not consider yourself a “fanatic gamer”, so what role did video games play in your upbringing?

Sjors Rigters: True, I consider myself a gamer, but I’m not a fanatic, a so-called “hard core” gamer. Still, as long as I can remember, I always played video games. I owned a Super Nintendo, which I shared with my dad. We played a lot of Donkey Kong and Mario Kart together. I still play those games, as a matter of fact. One of the things I love about video games — especially open world games — is trying to find their boundaries, their limits. I am always on the lookout for the edges of the game map, for example, those places that you cannot normally access for one reason or another. Back in the day, I was obsessed with a racing game titled Midtown Madness (1999) and I remember once seeing what lies behind the surface of the game as I jumped with my virtual car on an impromptu ramp to reach an island nearby. I fell into the void, and all of the sudden I saw the guts, the inside, the backstage of the game, so to speak. It was like an epiphany. You can see the same tension in my documentary, the need — almost an urge — to find the boundary of the game, the place where it all falls apart. I played a lot of games as a teenager as well, often online. The same stuff that everybody else was playing at the time, like Call of Duty: Modern Warfare and FIFA. But to me what really mattered was exploring vast territories, searching for invisible walls, without paying too much attention to the predefined goals. These days, I play party games on the Switch with my friends and family. In short, games have played a big part in my upbringing and they still do, although finding the time to play for a considerable amount of time has become increasingly hard due to my work obligations. Nonetheless, open world games are still my go to genre when it comes to escapism. I am an explorer by nature.

Matteo Bittanti: What is machinima to you: a medium, format or a genre? Do you plan to develop more machinima in the future? How did you first learn about machinima?

Sjors Rigters: I have to explain that my documentary was originally conceived as a final school project and I kept developing it because I felt there was more that I wanted to communicate. I knew that the best way to achieve my goal, as a storyteller, was with game footage, thus machinima was the most appropriate format for the task. I set the goals that I wanted to reach with my creative process, I watched several works to fully understand what was feasible and desirable, and then I began working with the material at hand. Recording my own session was extremely engaging. It’s a process that requires so many steps —playing, recording, reviewing, and then editing — a tough, enervating activity, but also compelling. It’s very analytical and creative at the same time. I guess that’s what I love most about machinima because it forces you to look at the video game from a different perspective. Machinima opens up all sorts of possibilities. It’s relatively easy to use the game world and its assets like characters and props as placeholders for a story. Machinima is a great storytelling device. You can change so many settings, alter the locations, and turn the game into something completely different. And if you are really talented you may end up with something like Red Dead Redemption’s Wild Wack West, a modded version that introduces a plethora of new elements into the original game. It’s a great example of how flexible this medium can be. As I was working on my own project, I also realized that machinima is such a great way to explain the mechanics of virtual worlds to those who may not know anything about them. Machinima is a great pedagogical tool: you can show a scene from many different angles and points of view. Machinima is about taking full control of a video game and turning it into a learning experience. This is especially true of those games, like Grand Theft Auto V, that come with an embedded editor. All the tools are immediately available to the player and one can really make interesting experiments. I noticed that so many people are unaware of machinima. But the people who do know it tend to be obsessed. It’s like all or nothing! [laughs]

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the process of creating Polarized Interactions?

Sjors Rigters: Sure. As I mentioned, the video was meant as a complement, or rather, a follow up to my thesis which focused on the pervasiveness of neoliberal and colonial ideologies within video games, and especially Minecraft. I was interested in explaining how Minecraft actively encourages a neoliberal approach to play. In the process of writing my thesis I became especially interested in NPCs, non playable characters, within Minecraft. That research formed the basis of my video project which examines the behavior of NPCs within Grand Theft Auto V. I spent several hours analyzing how they operate within the simulated world and how they react to the player’s input. As I was developing my research, I realized that the most interesting activity of the game is related to moments of inactivity, that is, when the character is not doing anything “productive”. Thus, I spent a lot of time just observing the other characters as they go about in the simulation. You quickly realize that these open world games may look real, reactive, and alive, but in fact they simply exist for the player, which makes sense, the player wants to be entertained after all, but at the same time, they are a corrupted version of our own world, which deliberately puts the individual at the center of everything when in reality we are just part of a larger context. We must learn how to live together, but every message we receive is that we are special, unique, different, which is such a neoliberal approach to life. In games, this logic is even more radical. In my machinima, I consider NPCs a symptom of a larger societal and cultural shift.

Matteo Bittanti: Perhaps that’s the reason why so many people love video games: they give’em what reality is often unable to provide, that is, a sense of agency, control, validation, and power. As our lived experience becomes more and more unhinged and unpredictable, I expect gaming to become more and more popular. Going back to Polarized Interactions, is there any work — either book, machinima, or film — that was instrumental in your understanding of Grand Theft Auto as a complex, perhaps problematic, text?

Sjors Rigters: I consulted plenty of texts and videos related to the ideology of Minecraft, but if I had to mention an artwork that really influenced my understanding of the relationship between reality and simulation that would be Harun Farocki’s Parallel I-IV. Farocki was able to provide a fresh look at simulated worlds, probably because he was not a gamer himself. He noticed things that most people missed completely. That work gave me a vademecum, a series of crucial guidelines, although it is not a tutorial per se. Harun Farocki “played” video games in a very analytical way, in a sense, and I found that very inspiring. Another work that I must mention is the Finding Fanon series by David Blandy and Larry Achiampong. I loved it so much that I paid homage to the opening sequence of FFII by showing a guy who’s literally falling from the sky. I love how these two British artists used the cinematography of the game to create a compelling narrative that is completely unrelated to the original text. I watched Finding Fanon over and over until I felt like I fully understood their process and I was able to make my own documentary. I deconstructed their videos, learning how to change camera angles to achieve my narrative goals. Finding Fanon is an impressive technical achievement, among other things.

Matteo Bittanti: Did you intend from the very beginning to use such an unusual, yet fascinating, ratio, to emphasize the repetitive nature of the simulation? Was Polarized Interactions meant to be exhibited as a two channel video installation preferably/exclusively?

Sjors Rigters: Yes indeed. The work was meant as a two-channel installation because I wanted to compare and contrast similar situations, but also show the same event from different perspectives. I love the repetitive nature of gaming, the fact that NPCs keep doing the same stuff over and over, and that we consider this stuff “completely normal”. By using two screens, I was able to juxtapose various situations and emphasize this sense of repetition. Once again, I was inspired by Farocki and the idea of showing parallel situations, so to speak, to stress the kind of polarized interactions we see in these games, not to mention the submissive nature of NPCs. In short, the format closely followed my intentions. It all made sense to me and I hope it’s clear to the viewers as well.

Matteo Bittanti: Polarized Interactions was originally developed and presented as your final graduation project at the Royal Academy of Art, The Hague in 2021. How was it received? What kind of feedback did you get? Anything surprising?

Sjors Rigters: I was surprised that so many people did not understand what they were watching. Some thought it was just CGI. They did not know that one can make a brand new story by appropriating and repurposing a video game. They still have these primitive, limited ideas of what a video game is, what it looks like, and what it can do. They may know that the game industry is bigger than cinema, TV or music, but they still consider gaming a puerile activity. So I enjoyed explaining to these people just how advanced games have become. Not just technically, you know. I think they understood the point that I was trying to make. Again, machinima was a very effective didactic tool.

Matteo Bittanti: Video games are generally lauded for their interactive nature. The video game is a medium that allegedly gives players some kind of agency. However, you deliberately created “scenarios in which the player passively interacts with non-playable characters in the game”. How do you reconcile the active, engaging nature of the video game with the passivity of the interactions with the NPCs that you show throughout your documentary?

Sjors Rigters: Well, a game like Grand Theft Auto V is specifically designed to encourage some kinds of interactions over others. In this case, bellicose, violent interactions. There’s not really an option to choose more diplomatic ways of tackling an issue, so to speak. Characters basically hit and shoot each other all the time. I became aware of this phenomenon when I watched How to Disappear: Deserting in Battlefield by Total Refusal. Brilliant stuff. Anyway, in Grand Theft Auto V no matter how hard you try to be a pacifist, violence is inevitable because it is codified. For instance, if you stand too close to a paramedic standing next to an ambulance, he will start hitting you. So you end up in the same hospital where he works, which is ironic and yet completely normal in San Andreas… So NPCs are like puppets in a world where there is no free will: they all have pre-assigned roles and their behavior cannot diverge from the designer’s intentions. One again, these games are sold to gamers as the epitome of freedom, but in reality, they are extremely limited. So, in a sense, Grand Theft Auto is an effective satire of the Western world because the same biases can be found in our society, where a superficial variety of goods barely masquerades the homogeneity of our lives, roles, and functions within the system. In a game there’s really no difference between a tree and a “human” character. They just have different attributes and textures, but in the end, they’re just code. These paradoxes are helpful for us to think about our position within the reality that we inhabit. The passivity of our interactions with the NPCs is a helpful reminder for us to understand the boundaries, constraints and limits or the game…

Matteo Bittanti: You also highlight some gender and racial biases embedded in the game. Do you think that the designers were aware of these issues? American artist Grayson Earle — who critically examined one of the many paradoxes of Grand Theft Auto V — suggests that biases are mostly unconscious, although their effects are no less “tangible”…

Sjors Rigters: This is a really good question, but I’m afraid that I can’t provide an answer, even after my research. Nonetheless, I still think about it, long after my graduation. So many game mechanics are based on “fixed concepts” that we have about our world. We tend to take for granted so many things, and we accept as “natural” stuff that makes little sense. Point in case: cops don’t fight each other in Grand Theft Auto, as Earle cogently demonstrates. And yet that’s just accepted as “reality”: it’s another “fixed concept”. On the other hand, Grand Theft Auto V is a satire, a caricature of the US and Western culture as a whole, so it’s hard to tell what’s intentional and what is not. Just look at the crazy billboards disseminated through the Los Santos: they are so grotesque! In short, the issue of purpose and intent is central and that requires close scrutiny.

Matteo Bittanti: In your work, you tackle the influence between simulation and reality, not to mention the reverse relationship. Specifically, you question the very notion of the player’s desires and the artificiality of most interactions, with obvious consequences on our social, shared contexts. Are you suggesting that reality itself is becoming more and more like a simulation, as Jean Baudrillard suggests (“the logic that informs ‘reality’ is the logic of simulation”) or are you a believer of Nick Bostrom’s hypothesis that “we all live inside a simulation”, e.g., The Matrix?

Sjors Rigters: I am inclined to suggest that reality is becoming more and more like a simulation. I don’t think most people are aware of how digital gaming provides a vocabulary, a set of metaphors, concepts, and behaviors. I am not suggesting that games program people to behave in a certain way, but I am certainly aware of their influence on my subconscious. It’s not just games, obviously: television and movies also influence or even shape our understanding of the world. And before audiovisual media, it was the novel. Games are the novels of our age. Unsurprisingly, our world is becoming more and more like a simulation while simulations are becoming more and more like our world. It goes both ways, in a sense.

POLARIZED INTERACTIONS

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 7’ 21”, 2021, The Netherlands

Created by Sjors Rigters

Director, Editor, Writer: Sjors Rigters

Made with Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013)