Freeroam À Rebours, Mod#I.1

4K video, single-channel-projection, color, sound, 16’ 13”, 2016-2017, Germany

Created by Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler

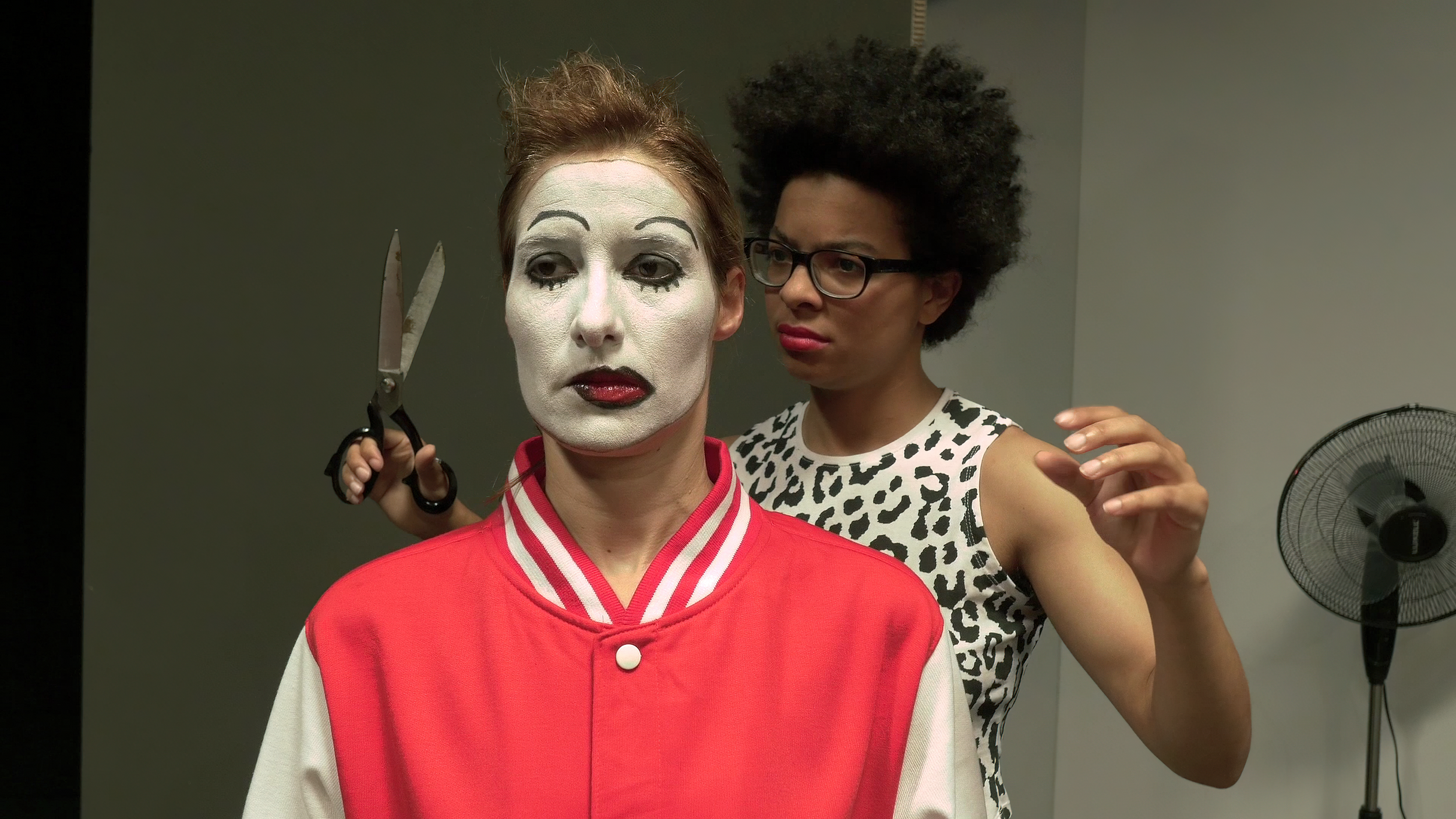

Freeroam À Rebours, Mod#I.1 is a 16-minute video work combining experimental film, music video, performance, and contemporary dance which examines the stilted behaviors and motions of avatars controlled by humans in video games. The avatars demonstrate awkward gestures, repetitive motions, and failures to perform actions. Groups of live dancers and actors physically reenact these movements in a series of situations. Their bodies recreate the avatars’ gestures and repetitions. The performers interact with constructed sets and environments that resemble video game aesthetics. The scenes cut rapidly between the choreographed reenactments and footage excerpted from the games, literally juxtaposing the human and the post-human.

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler explore contemporary media and its effects on the mind and body through video, photography, installation, and text. Panhans (born in Hattingen, Germany) undertakes a mental archaeology of hyper mediatization and digitalization, examining their influence on the mind and power relations in society. His work also engages with racism, celebrity worship, stereotypes, and diversity. He studied at Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg. Winkler (born in Fällanden, Zurich, Switzerland) examines similar themes through sculpture, video, and installation. She studied at Slade School of Fine Art in London under John Hilliard and Bruce McLean, after completing a degree in Visual Communication at Hochschule für Bildende Künste Hamburg under Wolfgang Tillmans and Gisela Bullacher. Together, the duo create interdisciplinary works that critically investigate contemporary media culture and human-technology interactions through experimental aesthetics. Their collaborations take the form of video, performance, and installation.

Matteo Bittanti: Freeroam À Rebours, Mod#I.1 explores the intersection between the simulated worlds of video games and the physical world. This exploration seems to thrive on the cognitive dissonance created by re-enacting avatar and NPC behaviors, which are familiar yet inhuman – not superhuman but posthuman. What draws you to highlight these “failure scenarios”' where game characters break their illusion of humanity, and how does this spotlight the epistemological short circuit between virtual and real worlds? Meanwhile, video games, particularly open-world games, attempt to replicate real-life freedom within their programmed confines. Freeroam À Rebours, Mod#I.1 suggests a subversion or reversal of this freedom. How does your work engage with video game aesthetics and the concept of free roaming, balancing the illusion of unscripted freedom against the inherent constraints and limitations of game worlds? Are there specific artistic opportunities you find in this space between perceived freedom and actual predetermined nature of video games? Does your work also aim to create spaces of openness and improvisation within the video art format, challenging or redefining these boundaries?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: Well, first of all you have to know that we are everything else then gaming specialists, or theoreticians – we just came across the GTA 5 Free Roam version by reading an interesting essay in the Süddeutsche Zeitung back in 2015. The author attributes to it the qualities of a work of art. because it brings all kinds of more or less unconscious desires to light just by how the – mostly male – players perform in it. We then found ourselves watching hours of GTA 5 Free Roam YouTube gaming sessions and were flattened at first by the amount of surreal hardcore spectacles we were presented with in these really well-designed hyper-realistic landscapes! Having never played computer games before, we watched and still watch all these clips the way you watch movies, which means that we don’t have the directly controlling connection between player and avatar as a gamer has. You could even say we experience it more as actors acting, as avatars being played, if you know what I mean. After a while we got more and more hooked on the strange idling modes, the numerous different kinds of uncanny glitches in their movement sequences in relation to human movement and especially also in their strange “social behaviour”. We really wanted to hold on to this stage of fascinating phenomena of “inadequacy” before it disappeared completely due to the ever-increasing perfection of CGI gaming engines. We sympathized with this inadequacy and the oddities from the very beginning and much preferred to focus on them rather than following the perfect flow of action games. An ideal which, in our view, underlies more or less every mainstream computer game and which, by the way, also threatens to increasingly define our hyper-capitalist world at all levels. The entire cast and crew really enjoyed turning the story a few steps in reverse, ‘à rebours’ by having the humans learn from the avatars instead of the other way around, and furthermore by learning their ‘mistakes’ instead of the perfect action. That was the idea behind this film, which turns out to be a “dance of insufficiency”, as an art critic once so beautifully titled her article in taz magazine. While computer games reveal an ideology of practising skills, efficiency and optimization, the characters in the video show an aesthetic of failure and a choreography of hesitation that is revealing in the context of current theories of passivity and incapacity. If the contemporary subject is increasingly trimmed for maximum self-optimization with its flip side of depression and addiction, the unintentional passivation of the characters in the computer game formulates an almost utopian content.

The world is still “open” on some of the side paths, in some “hideaways”, folds, cracks and little holes in the surfaces, that’s where we want to work.

Matteo Bittanti: The re-enactment of avatar behavior by human beings has a long tradition in contemporary art. One example is Brody Condon’s Death Animations (2008), which was inspired by Bruce Nauman’s 1973 videoTony Sinking into the Floor, Face Up and Face Down as well as role playing video games. Yet recently it has become a social media trend, as popular TikTok performers like Fedha Sinon, also known as PinkyDoll began acting out game motions for monetary goals. The popularity of these videos, which present a clear hyper-sexualized tone and an objectification intent, making them closer to pornography than performance art, is not surprising. As artists who have explored for several years the video game-to-IRL re-enactment process, what is your take at this “normie trivialization”? In fact, the mainstreaming of this phenomenon reached its apex in 2023 thanks to the coverage by The Guardian and The New York Times. How might artists reclaim and elevate forms that have now become “monetized” online and banalized through vernacular discourse? Or is this entire “genre” now definitely exhausted? In other words, there won’t be a Mod#I.2?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: No, till this day there is still no Mod#I.2. The title detail Mod#I.1 was thought on the one hand as kind of anti “this-is-the-one-and-only-choice-made-by-the-artists-genious-decisions” statement, referring to the potential possibility of other edit versions from the many takes we made, and on the other hand we really speculated about a second, endless installation version for the exhibition context with computer generated constantly randomly re-rendered edits in real time. In the end, we had neither money nor time for it and just let it go. At the moment, there is no Mod#II version planned or anything like it.

But anyhow, it’s an interesting question – is it still possible to work with avatar reenactments in interesting ways that perhaps new questions can be raised? If we for example look at the found footage genre, some years ago it seemed to be somehow “closed”. The work of some artists who became famous for this kind of genre seemed to have already exhausted the topic. They mostly used cinematic film details in their very own and interesting ways, but then the “internet turn” just brought so many new possibilities and context to it, that there is a lot of new and exciting stuff done at the moment. So just let’s see what the future will bring. No genre is really dead for long, there are always new possibilities rising after a while.

Matteo Bittanti: As you mentioned before, Freeroam a Rebours explores the idea of “practicing insufficiency” by dramatizing e glitches and limitations of video game avatars. Why does highlighting and embracing defects provide an appealing alternative to the pursuit of optimization and perfectionism, the main elements informing that dogma that Byung-Chul Han calls psychopolitics? What do you find artistically and conceptually intriguing about imperfect non-human (or non-human like) behaviors?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: First and foremost, for us it was and is an almost physical sympathy and a joyful delight in the mistakes and shortcomings of the avatars, but also of the players, that provided the impetus for the work. RAGE (Rockstar Advanced Game Engine) and many other CGI worlding engines just weren’t as perfect as some would have liked. (Let’s see what GTA 6, which was recently announced for 2025, more than a decade after the last version, will bring). It’s a consistent theme in our work that we are all trained and conditioned to self-optimization and perfectionism on all levels and in all sorts of ways to keep hyper capitalisms machines running – so contemplating, practising and celebrating imperfection felt at least a little bit resistant. And according to Han’s thought that the popular slogan “property is theft” has been replaced by another: “privacy is theft”, one could perhaps also say glitching, idling, and insufficiency is theft too.

Matteo Bittanti: In a society that glorifies productivity, optimization, and economic success over other ideologies, your work explores alternate modes of being like idleness, insufficiency, and failure. How do you see these “imperfect outcomes” challenging the dominant neoliberal narratives of human capital and ceaseless efficiency? What space and value do you see in cultivating forms of “passive” non-productivity? Are glitches a form of (un)intended sabotage, like throwing the wrench into the machine, in a gesture of luddite disdain for technology? Is the dramatization of the glitches and limitations of automated systems a tool for reimagining our own relationships to achievement and self-optimization or the recognition that have now become the de facto normative aesthetics of the 21st century?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: Yes, our hope is exactly this! It also interests us in the face of e.g., solutionism, this techno-belief-system that every problem could be solved by some (highly marketable) tech solution (which brings all sorts of new problems with them, which then can be solved by new highly marketable tech solutions and so on and so on), that abandoned the past entirely and rather considered emigrating on a new planet than saving the very only one we have – just in case the plan that all problems can be solved with new technologies might not quite work out as perfectly as planned…

Matteo Bittanti: In addition to the intent behind the project and the formal structure of the product, i.e., the video, I am very interested in the process. To create Freeroam À Rebours, you collaborated with a choreographer and several performers to translate the “deficiency scenarios” of avatars into physical reenactments. How did you approach transforming these digital anomalies and displacements into human movements? The camerawork and editing mirror video game aesthetics and present a “propulsive, rhythmically structured montage.” How do you see this dynamic visual language intersecting with the themes of insufficiency and failure in the avatar’s actions? Does the pacing and motion here reinforce or contrast with the imperfections being dramatized?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: After having seen endless hours of gameplay footage, we made a choice of scenes or small snippets of movements that attracted our attention and worked with our concept of “hesitation and insufficiency”. The choreographer Miriam Sögner then taught the performers the movements – which meant they had to let go of their human natural movement, and then take on the new movement, somehow like rewriting a hard disc, they “loaded” a new movement program into their bodies. Simple things like standing for example involve a new concept, or in particular the so called “idling”, this rather odd movement that resembles wobbling to show you are not dead. After ten days of rehearsing the performers were capable of reenacting the avatar movement in such a way, that experienced game players watching the film afterwards told us that they could even spot the generation of the game, that it was GTA 5 and not 4.

Initially, we also thought about whether it would be exciting to use robotic cameras to get aesthetically close to the disembodied “camera” in the game. But we quickly came to the conclusion that it would be much more fitting if this “machine” was also imitated by a person, a human being. In the progress together with our D.O.P., we found out that the camera not only has to capture what happens, but has to give impulses herself, like the gamer who controls and leads the “camera” in the game. Randomly and abruptly changing directions, with no filmic plot logic. We feel like neither its reinforcing, nor its contrasting the imperfections, the way the camera work relates to that in the game goes along with the way the movements of the performers relate to those of the avatars. Human beings imitate machines imitating human beings.

Matteo Bittanti: In Freeroam À Rebours, expensive supercars make recurring appearances, referencing similar status symbols that feature prominently in games like Grand Theft Auto. This seems to suggest an ideological affinity between gamers and car enthusiasts, the so-called petrol-heads – are you suggesting that the gamer use the virtual world to compensate for real-world limitations, achieving status through expensive virtual possessions like luxury vehicles? Furthermore, in your 2021 installation DEFENDER, gaming chairs were used to strengthen the affiliation with SUV owners. How might the prominence of high-status polluting cars in Freeroam À Rebours and DEFENDER relate to notions of compensation, aspiration, hostility, aggression, and social signaling through commodities, virtual and tangible? Overall, what connections might you see between gamer culture, materialist status symbols like cars, and how your work critically examines social relations and ideologies through virtual and real worlds?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: Thank you for this question! There’s a quote from a car engineer saying that when it comes to the purchase of oversized vehicles or supercars, rationality is out the window. Somehow we know that the construction and maintenance of these kinds of cars destroy the very basis for our continued existence without return, but nevertheless we want them.

Looking at tons of SUV ads and their messages they’re only meant for individuals, a single man or woman that conquers an obstacle, a setback, or a difficult period in their life – obviously with the use of a car!, and that this object would survive (or maybe has survived already) the world’s end — hurricanes, pandemics, fire and brimstone. It’s the apocalyptic promise right out of a computer game. I just wonder whether the car industry has long since realised that the only way to sell cars is through a kind of “gamification”. Through a recent documentary on the history of images and how manipulative they are (this is a very short summary), we came to the speculative conclusion that films like Star Wars only exist to prepare our brains for the commercial break, all synapses wide open for that coke bottle or SUV…

We can’t speak for all computer games, but many of them are about battles, losers and winners. And if you’re driving your mega-thingy vehicle, you’re certainly not a loser. It works as an extension, or substitute of self-optimisation, it’s the tight space in a rapidly changing world that you can be in control of. At least you can optimise yourself and feel like the captain of the streets and your life in your sexy, safe, drive-through-everything bolide.

The concept of the car as it is promoted in these ads is an individuality-machine, it’s a safe space for a single person and their peers, separated from the ugly real world. (In DEFENDER we coupled these commercial fantasy mish-mash, with self-optimisation talk and evangelical mega-church-screed, the latter with striking similarities, as they foster the neoliberal dogma of the individual fate (social responsibility is more and more transferred solely onto individuals – it’s your very own fault if things don’t work out for you, you didn’t try hard enough to succeed!) As Tom McCarthy wrote in his essay on DEFENDER in the exhibition catalog for our show at HMKV Dortmund: “It seems these cars [or game plays, or mega-churches…] still providing its occupant with ‘access to God knows how many TerraTETRAbites of songs and movies and series that are included in the package.’ What it won’t provide them with, though, now or ever, it seems, is salvation, or the blessing or success it dangles before them, or even a habitus, a state of haptic and psychic AT-HOME-ness, of being integrated with a place and situation.”

Matteo Bittanti: Just like Freeroam À Rebours, your more recent work Bringing the WoW Home (2020-2021) involve the reenactment and dramatization of gestures and poses derived from video games, transposing movements conceived in virtual digital spaces into performances by physical – as in “made of flesh and bones” – human bodies. In lieu of these works sharing common creative processes, how has your approach to translating the motions of gaming avatars into corporeal enactments by actors evolved across these two projects, beyond their manifest differences in format?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: We think GTA 5, to which Freeroam refers exclusively, is rather a special case in this respect. As far as we know, you can’t construct or design all the details of your avatar yourself, as in some other games. It is more about clothes, haircuts, cars, weapons, and other attributes that you add to a pre-made character. In the research process for finding a costume concept for our film, we became particularly interested in the relationship between the styles and clothing of the avatars in GTA 5. Pieces of clothing from different decades from the last, say, forty years can be completely detached from the original attitudes, such as a youth movement like, e.g., punk or rock and roll, selected, mixed with others, ranging from gangsta rap to (urban) tourist to terrorist or vintage guerrilla and swapped almost endlessly in fractions of a second for any other. We found this an astonishing culmination of what can also be observed in the real world. An ever-faster spinning carousel of (retro) fashion styles that no longer have any connection to a specific, possibly even political stance and become a – to put it positively – carnivalesque free play of signs and references. On the other hand, however, one could say that it is also an ever-accelerating, idling, extremely market-driven and particularly consumerism and sales-oriented carousel.

Matteo Bittanti: Whereas you utilized video as the medium for Freeroam À Rebours to dramatize puzzling digital behaviors, loops and glitches of the Grand Theft Auto universe, your more recent work Bringing the WoW Home employs still photography to capture extreme emotions and aggression typical of fantasy role playing games such as World of Warcraft. What drove your decision to shift media from the moving image to static portraiture for exploring gaming-inspired poses? In other words, what distinct artistic goals or sensibilities aligned with capturing passive avatar activities through video art versus portraying intense combativeness via photography? As a media scholar, I am interested to hear your thoughts on how the specific features of each medium suited the shift in focus from inefficient actions to overt tensions between these consecutive works inspired by video game culture.

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: What the Bringing The WoW Home series is based on is not captured out of sceneries from the game itself as we did it for Freeroam À Rebours, but from the large pot of merchandising images of the WoW “Heroes” that can be found on the internet. These images have a certain quality on their own and are a little different from the aesthetics of the game itself. It is more about the extremely aggressive gestures in them, the big, heroic, warlike poses prominently supported by the chosen perspective, and the facial expressions that go with them that caught our interest. The game itself feels nearly cute and fairy-tale like in comparison, and the graphics are much less detailed and not made for looking at individual face mimics or selected poses. These images seem to serve to convey something that the viewer then associates with the game - something like the actual “spirit” of the game maybe, which does not appear at all in the hectic, technoid gaming stream itself but is perhaps always involved in the psyche of the players to identify with during gaming. So it is easier than you might have thought – we just reenacted moving images with moving images for Freeroam, and Lisa and I reenacted images in photographic images.

Matteo Bittanti: In her brilliant critical text, Celina Baljeet Basra observes that the photographs in Bringing the WoW Home reveal a “superhuman tension” exceeding what the World of Warcraft avatars themselves can portray or manifest. She also notes how games often exaggerate poses and expressions to convey emotions clearly, in a theatrical manner. This connects to ideas Tom Gunning and André Gaudreault proposed about the so-called “cinema of attractions”, before narrative integration and the introduction of sound in the late 1920s. Given these perspectives, I’d like to ask: do you see contemporary video games as inheriting a certain theatricality that cinema has since abandoned for the pursuit of “realism”, even in the hyper-realism of special effects? In your view, are highly stylized, combat-focused role playing games like World of Warcraft closer in spirit to theater than cinema in how they depict facial expressions? As you translated WoW’s exaggerated but confined virtual gestures into real physicality, were you also seeking to comment on gaming’s theater-like aesthetics in any way?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: Even though we weren’t referring to scenes from the game itself but to the merchandising images for it, it’s a very interesting question. Because when Lisa and I did this photo series together, we realised that exactly as a professional actress, she enjoyed it so much because this kind of over-the-top exaggerated overacting is an absolute no-go in theatre and especially in contemporary film productions. The question of realism in film is a very interesting topic anyway, what exactly is meant by the term, and why has this one-dimensional interpretation of realism become so prevalent? Even though, as I said above, I am not a gamer or a gaming expert, I can still see that computer games are simply not thought of in such categories. Realism, like in films and photos, is just not possible or desired at all. Even if the graphics in some games try to depict parts of our visible world hyper-realistically, there isn’t this physical indexical aspect that gives photography and film their special position, that connects these media to the real world uniquely, so that it’s inevitably intertwined with the interesting but highly problematic concept of the possibility of true authenticity in representation. Games simply lack this special connection to the real world.

Matteo Bittanti: In If You Tell Me When Your Birthday Is, you blend analog and digital elements into a surreal machinima drama starring glitchy game avatars. Their absurd, computer-like conversations evoke the uncanny – often involuntarily funny – interactions between humans and chatbots. Were you more interested in amplifying the weirdness of bot-speak by using machinima? Or did you hope to uncover hidden humanity in our exchanges with AIs? More broadly, as artificial intelligences become more conversationally adept, do you see the boundaries blurring between human and machine modes of communication? While bots may be becoming more “efficient”, are we also increasingly adapting our language to be more machine-like (prompting) when engaging with each other? I’m curious if this piece reflects on how our speech patterns shift as dialogue with machines becomes more commonplace.

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: I like you talking about prompts – in examining the conversation and language of chatbots, it was very clear that this can only capture a particular moment of a larger development, as it will change rapidly on the fly, so to speak – and has just reached now with OpenAI’s chatGPT a completely new and surprisingly high level. While researching for our work back in good old pre-chatGPT 2020, which now appears like the stone age of chatbot technology, we discovered some similarities to a pidgin english, a simplified form of language stripped of complex grammar with a limited choice of words (which was coined in China in 1855 by attempts to pronounce the word “Business”, and was mainly used to enable trade) – when we speak to “machines”, in order to get what we want we as users must also adapt to the machine’s capabilities, that means shortening sentences, avoiding nested sentences, and any complexity – when we speak to Alexa, we have to say “Alexa” first, otherwise she won’t respond at all – at that point, AI-based language felt downright dumb, but also like a doctrine, it’s highly political when a few companies have the power to dictate what we can and can’t say, especially since most chatbots are in English to begin with. (The effects of the “linguistic capitalism” could take up a lot of space… In fact there could be the potential to also use machines and machine learning to keep language from disappearing, rare languages for example, it has to do with the purpose and who is programming it. At the moment it’s mainly for capital gain.) We see that the influence of social media is changing our language habits, shorter, and at times unfortunately more rude language. Language is a very fluid thing and not fixed at all in our opinion, and whoever is in power will try to control it in their ways. Our task as artists is to somehow try to control and subvert it in an enlightening way, so that we don’t get stuck in an endless loop of performing and speaking in Beckett-like AI sceneries like the two CGI World Desperadoes do in our video. (Communicating with AI is in fact “Waiting for Godot”, haha, the very other thing will never arrive, you will always remain in the AI spectre.)

Matteo Bittanti: In If You Tell Me When Your Birthday Is, you intentionally allow the seams between analog and digital techniques to remain visible, rather than smoothing them into seamlessness. Similar to your emphasis on glitches and passive behaviors in Freeroam À Rebours, you again give the deficient, the imperfect and flawed a central role here. What do you find compelling about reveling in glitches and transparency of process specifically when exploring the blurred boundaries of virtual and physical realities? Are you implying that the glitch exemplifies the quintessential nature of the digital? Or does foregrounding those cracks and fissures allow something truer to be revealed about our increasingly technologized modes of communication and connection?

Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler: It started with our research residency at the Academy of Theatre and Digitality in Dortmund in 2020. Given the possibility, we tried out a variety of tools to create a kind of digital world in which we liked to “shoot” a machinima film. We got fascinated by mixing professional world building programs like Unity with e.g. the interesting effects and bugs of the freeware smartphone app Displayland for example. With the help of some coders we could also combine it with motion capture technique and could even shoot parts of If You Tell Me When Your Birthday Is by moving inside our former CGI created world with VR goggles! It is a really fantastic crazy mix of techniques combined in this video. We had the feeling, that we should work exactly with all these cracks and fissures that we had produced, to just leave them visible, because we didn’t want to join the endless production of perfect, closed surfaces – on the contrary, we wanted to make it a “bad machinima” thing, as a kind of digital counter world that would fit to the absurd chatbot dialogue and our feelings about the reality of the digital part of our allday life – where you e.g. stumble from one dumb answer machines digi-voice, which is not at all understanding the problem your in, to the next stupid buggy so called AI driven robot and back again. Meanwhile the time slot for unlocking an account with a passport closes and everything starts again and so on and so on.

Freeroam À Rebours, Mod#I.1

4K video, single-channel-projection, color, sound, 16’ 13”, 2016-2017, Germany

Created by Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler, 2016-2017

Courtesy of Stefan Panhans and Andrea Winkler, 2024

Produced and Directed by: Stefan Panhans

Concept: Kathrin Busch, Stefan Panhans

Director of Photography: Lilli Thalgott, Eike Zuleeg

Production Design: Andrea Winkler

Choreography: Mirjam Sögner

Original Music: Kirsten Reese

Performance: Olivia Hyunsin Kim, Judith Nagel, Lisa-Marie Janke, Anne Ratte-Polle, Matteo Ceccarelli, Ixchel Mendoza Hernandez, Gyung Moo Kim, Zwoisaint Boliver Patricia Mears-Clarke, Hannes Wegener

Camera Operators: Lilli Thalgott, Eike Zuleeg, Florian Winkler

Phone Cam and Screer Recordings: Kathrin Busch, Stefan Panhans, Lilli Thalgott, Andrea Winkler

Light: Lilli Thalgott, Eike Zuleg

Assistant Director: Andrea Winkler

2nd Assistant Director: Simone Bogner

Set Manager: Kathrin Busch

Casting: Stefan Panhans, Mirjam Sögner

Costume: Andrea Winkler

Make Up and Wardrobe: Muriel Nestler

Postproduction: Wolfgang Oelze

Funded by Medienboard Berlin-Brandenburg