Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog I-III

Digital video, color, sound, 13’ 51” (part I: 6’ 02”; part II: 4’ 17”, part III: 3’ 33”), 2009, Germany

Created by Sebastian Blank

Sebastian Blank was born in 1977 in Saskatoon, Canada. He studied audiovisual media at the Bergische Universität Wuppertal. His practice explores, among other things, the inner workings of the art world. He now lives and works in Cologne.

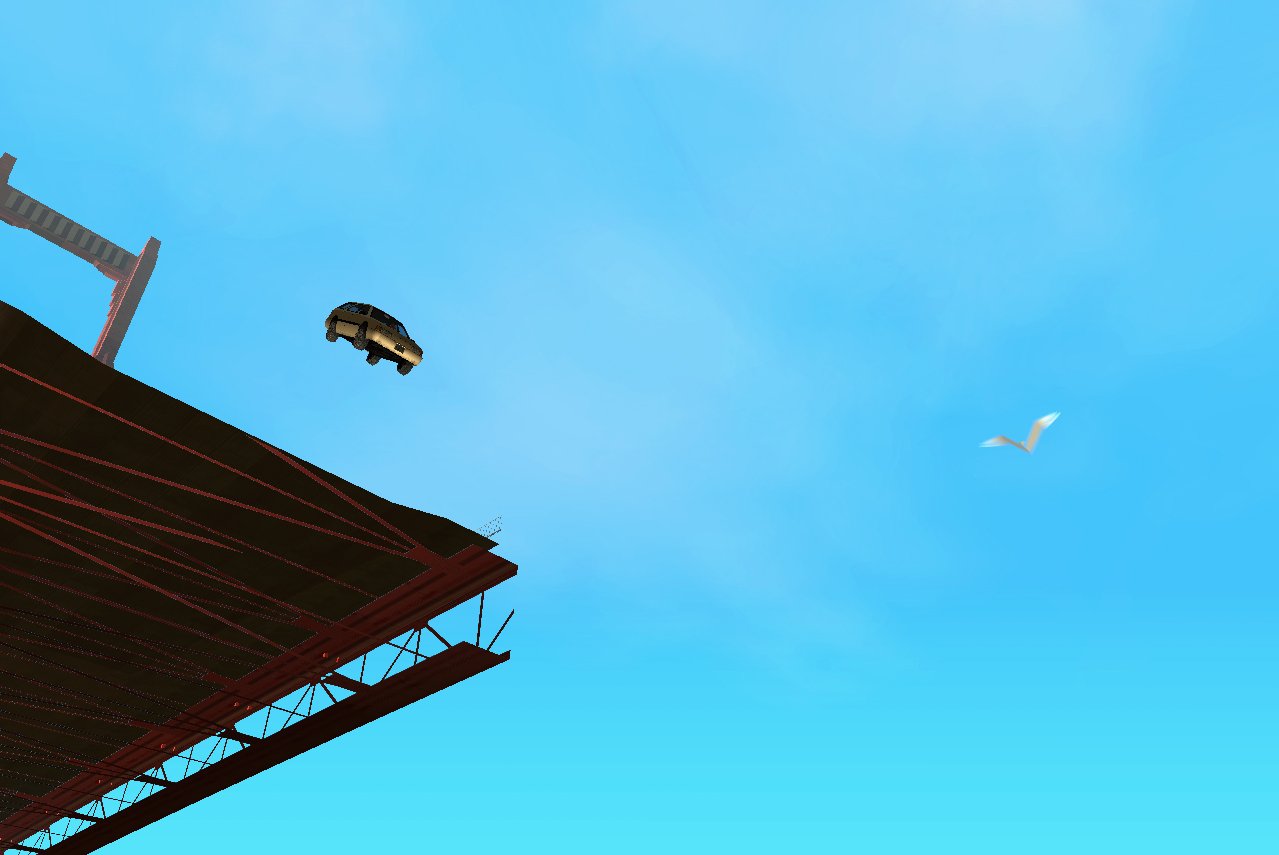

Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog I-III (trans. A dialogue between art and society I-III) is a trilogy of machinima, a form of video art created by appropriating, manipulating, and repurposing video game visuals. In this case, the artist modified the popular Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2009) by introducing themes and elements completely alien to the original game. Specifically, the trilogy focuses on the relationship between society and the artworld, using game spaces as a performative context for the artist.

Matteo Bittanti: I’m very interested in learning more about your own relationship to video games and video game culture. Can you elaborate?

Sebastian Blank: I would say that I have an average relationship with video games. When I first discovered video games as an adolescent, I was fascinated by this new medium like many of my peers. Digital games introduced experiences that were impossible before. Not only were they so innovative, but games were evolving very fast. Thanks to technology, we quickly got more colors, better resolution, and smoother graphics, which in turn allowed for better immersion into the games I played. And playing, in contrast to gaming, also included investigating the limitations of the simulated environments, for example by driving off the track in early racing games, only to stumble upon “transparent walls” too soon. The determination of those early worlds certainly stimulated my urge to find out what lay beyond those borders and to try to find a way to get there – which of course never really worked. But the desire to go beyond and to change the rules stayed with me. Nowadays, I only play occasionally. What really interests me are conceptual indie games like Bennett Foddy’s Getting over it or visual experiences like Radiohead’s Polyfauna and Kid A Mnesia, and of course I am always on the lookout for artistic interventions.

Matteo Bittanti: A recurrent theme in your oeuvre is the connection between photo realistic spaces and virtual performances. What is the relationship between Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog and your project Artmart (2006)? The billboard on the simulated road says “Own Art Now”, a clear reference to Artmart. Is the artistic process a mere synonym of conspicuous consumption, in your view?

Sebastian Blank: In framing my question of “What if art had a higher status in society?”, the medium is a means to an end – in my case, photography or the game Grand Theft Auto. Artmart is the most important gallery chain in my world. It only became so because it offers good art at fair prices, supports cultural producers, promotes artists and invests a significant part of its turnover in targeted marketing activities. The claim “Own Art Now”, which Artmart had written by a large agency, appeals to collectors and artists alike.

Matteo Bittanti: Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog is one of the earliest examples of machinima in which the original source – the hyper-violent Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004) – was cleverly subverted to address themes alien to the game, specifically, the relationship between society, culture, and art. What prompted you to engage in such gestures of irreverent appropriation and modification? Can you describe the origin of the project? How and when did you learn how to modify games?

Sebastian Blank: I can think of two distinct starting points that led me to modify this particular game. First of all, I felt that San Andreas was a good visual fit for my photographic work. Let me elaborate a bit on this. The original idea of my work is, after all, a world in which art and culture play a much more important role than they do in our current reality, which —in addition to greater acceptance and distribution of art — ultimately leads to larger galleries or even gallery chains operating in the art market. That’s how Artmart came to be. And Artmart, of course, advertises in places where we would not expect art to be advertised in our real world, such as along the highways of Suburbia. Art is so omnipresent that you encounter it even in supposedly inappropriate places. Fortunately, there are a lot of these non-places in San Andreas, which is why – in addition to the colorfulness of the game – I decided to create my utopia there. How exactly the social and artistic structures function within this utopia, what my world means for the art that is bought at Artmart or what kind of art people buy there, I deliberately leave open to interpretation.

If you look at the monolith from part I, the bridge from part II, and the demolished cars from part III, they don’t fit into the utopian picture for now. Maybe these are counter-positions to my utopia, a quasi rebellion against the artist as creator. Or maybe they are counter-positions within the utopia, in the way that there are groups within the game who are not satisfied with the utopian society and its art system and therefore express themselves through radical art forms and gestures. I try to open up interpretive spaces for the viewer as to what these representations can mean.

The second reason why I used GTA San Andreas is because I could. My intrusion into the game was, in a sense, the game itself. At the time, I played GTA Vice City with great enthusiasm and, at some point, I discovered the existence of a lively modding scene [an entire subculture of players who alter the characteristics of original video games, from the visuals to the gameplay, Ed.]. That awakened in me the playful motivation to modify the game as well. The forums were primarily about modding cars with more realistic skins and such, but knowledge that such an intervention was possible in the first place became the starting point for me to try it as well. With the artistic background I just mentioned, I knew I would go beyond simply modifying the cosmetic aspects of the game and towards an artistic idea. Therefore, I started to modify objects in Vice City and then later in San Andreas, which had a similar structure. There were various community-written tools for this endeavor, which you have to think of more as scripts or bad beta software, but these tools could read data from the game, convert it, and write it back. Since I was a graphic designer and knew a bit about textures and 3D objects, I was able to create my objects in Blender and bring them into the game using these tools.

Matteo Bittanti: Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog I opens with the image of highways, overpasses, and intersections. Marshall McLuhan famously argued that the road is the major architectural achievement of the 20th century. In many ways, Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas can be considered a racing game, that is, a game about car culture. So, is the dialogue between art and society mostly a conversation about cars?

Sebastian Blank: It’s funny that this perspective has remained completely hidden from me until now, which suggests that I, too, have apparently been conditioned by the car as a medium that I no longer perceive it consciously.

Matteo Bittanti: In fact, Marshall McLuhan writes that technology and media create environments that become invisible to us. It is up to the artist to create counter-environments to make the former visible in all their impact and ramifications… Cars are perhaps the biggest medium of all. I mean, people kill each other with missiles and tanks for the “privilege” of driving an SUV, you know. The world is run by petrolheads.

Sebastian Blank: I have an emotional attachment to roads and when I think of bridges I immediately think of Jeff Wall’s The Storyteller but also his images Eviction Struggle or Overpass are set in places that I find intriguing. And, of course, I also have an emotional attachment to cars, which manifests itself in love and hate in equal measure. Here in Cologne there is a sculpture by Fluxus artist Wolf Vostell called Stationary Traffic, where he transformed his parked car into a concrete sculpture by simply filling it up completely with concrete. With this performance he very much questioned the medium of the car. I grew up in the country, where the car means everything, and I live in the city, where the car limits the quality of life to the maximum. If you are looking for a parking space, the car means imprisonment, but in the countryside, it means freedom. And probably the freedom of open-world gaming can’t manifest itself any better in any game than in Grand Theft Auto: namely, in pulling someone out of any car, just taking the car and driving it somewhere. Seen in this light, my subconscious appropriation of the game Grand Theft Auto as a medium can actually only be a message about cars.

Matteo Bittanti: In Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog I, art is like a giant monolite that interrupts the “normal” flow. Cars repeatedly smash into the ART monolith that materialized out of the blue on the highway. It seems that ART cannot be ignored or sidestepped: consider the insane traffic jam which culminates with explosions and death. An encounter with art can be lethal, even for the State, hereby represented by the police. Art wins, in the end, society loses. Is that a fair assessment, or am I completely off track?

Sebastian Blank: The nice thing about working with Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas was the reaction of the non-player characters. Their existence is intended to make the world seem as realistic as possible for the gamer. So, unlike multiplayer games where we play with other humans, here we’re dealing with computerized supernumeraries that even I didn’t know how they would respond to my modifications. Since the NPCs look human, that is, human like us, we as observers assume that their actions are based on an underlying meaning and will. However, the NPCs react radically differently from what we expect them to. As viewers, we therefore look for possible explanations. These depend on the clues I may give in the video, on the context in which it is viewed, and on our prior knowledge. One possible interpretation is that art wins and society loses. Perhaps society does not understand art, perhaps they cannot see it, perhaps they attack it but have no chance to defeat it. As for the creator of the monolith, well, we don’t know anything, except that it is obviously a sculpture and therefore art. Another reading is that what we see could also be a performance and that society, as a whole, participates in the process. So, it is about opening a space of interpretation that describes what art can do, what it gives us, but also about who is allowed to place it in the public space or who defines what art is.

Matteo Bittanti: Your trilogy was exhibited, among others, at Computerspielen. Perspectives of Play, a seminal exhibition organized within the context of the Next Level Conference 2013 at Dortmund University curated by Jonas Hansen and Thomas Hawranke. In the accompanying catalog, you describe your project as “utopian”, albeit with “cynical” implications. What do you mean? Are you suggesting that the Artworld is a hermetically sealed space which has no impact whatsoever on society at large, thus artistic experimentation is ultimately meaningless? Is L’art pour l’art therefore a failed endeavor, save for the economic value of artworks, which have very little to do with the artistic process in itself? Is the alleged conversation between art and society rather two distinct monologues?

Sebastian Blank: When it comes to cynicism, I was basically accusing myself of this, because utopias are primarily conceived to improve existing conditions. I have called it utopia, although there are dystopian elements in my utopia, which I have had in mind from the beginning. The economic success of art, which as you say doesn’t necessarily have anything in common with the artistic process, could be a dystopian element. But maybe it is a utopian element after all, because it is good if society also buys art and ensures the survival of gallery owners and artists. This ambivalence in interpretation interests me. It’s the same with the title: whether there is actually a dialogue between art and society in the video depends on how we interpret the actions of the NPCs and which part we are talking about. Are they or society part of art or do they oppose it? Both interpretations are legit so it might or might not be a dialogue between art and society. For me personally, art has to do with opening spaces of thought and giving hints of possibilities. These possibilities are then possibly the basis for social change, or they may not be. But they have meaning for some who want to engage with them. If art can produce a background noise of relevant issues, change can then grow out of that. When I think of Warhol’s car crash paintings, I think he was not only concerned with critiquing mass media and the attention economy of horror, but also with the car and its social role. At least that's my reading in the 21st century. And these readings can also change, so even an older work can provide new food for thought in a new context for some people.

Matteo Bittanti: Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog II is accompanied by a paraphrase of a famous quote by President John F. Kennedy: “It’s not about what art can do for society, it’s about what society can do for art.” Again, the video opens with the image of roads, highways, bridges, and other symbols of personal mobility. Here, Art is a journey, rather than a destination. Art is connoted as an experience, rather than an artifact, a product, an object. Your machinima seems to suggest that one can become artified through the application of “sublime software” after passing through a certain threshold, here represented by a toll station. Art is dangerous (“Continue at your own risk”, you’d better “watch out”). Art is an adventure, basically. But the ersatz Golden Gate bridge is interrupted: the adventure climaxes with death. Cars plummet into the ocean. Are you suggesting that in order to become an artist, the driver must first die, that is, abandon her or his previous identity? Is the artistic process a form of resurrection then, or just a personal or collective delusion?

Sebastian Blank: The second part of my trilogy goes back to my fascination with Fluxus and performance art, especially the artists’ directives for action, which were usually written very simplistically (but accurately) and had radical consequences. I’m thinking of Tehching Hsieh’s One Year Performances, for example, who writes “I shall stay OUTDOORS for one year, never go inside” or Chris Burden’s Shoot, where he gets shot in the arm, which was indeed performed in-game by Eva & Franco Mattes as a re-enactment. It is the radical nature of the performance that is expressed in the very simplicity of the words. It is the same in Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog II, where one can choose to become art or to take the last exit. Fluxus was about the unity of life and art, thus about living one’s life as art. This is incredibly radical and the performance in Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog II, if it were real, is even more radical, because it ends with the fall from the bridge. As viewers, we have to assume that this is fatal. In terms of art, this is the height of the sublime. At least, if we assume that the NPCs have free will.

Matteo Bittanti: In many ways, Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog is an experiment, a simulation. By modding the game, you were interested in observing the reaction of the computer controlled characters to an alien object, that is, ART. However, you wrote that their limited “intelligence” prevents them from fully engaging with it. This lack can be read as our own inability to understand the true meaning of art, that is, a transformative force in the public sphere rather than a rarefied artspace which is like a white cube. Are you suggesting that we are all NPCs, non player characters when it comes to art?

Sebastian Blank: Thinking of us as NPCs is a nice thought!

Matteo Bittanti: Actually, it’s an argument put forth by the Alt-right…

Sebastian Blank: But in our defense, I would refer to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs. Engaging in art is just not the most important thing in life. Nevertheless, it would be nice if it were. In the end, art reception is very much related to what one expects from art and what concept of art one applies. Maybe we can expect even more transformative power from art in the White Cube than from art in public space, which is rarely radical. In Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog, public art is also radical. In our world, the monolith would not stand in the middle of the road but at best on a traffic circle, but would have a fixed height, width, and color so that it would not endanger traffic.

Matteo Bittanti: Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog III is an adaptation sui generis of Ever is Over All (1997) by Pipilotti Rist. Once again, you were among the first artists to use digital gaming as a context for performance art. In the original work, a woman (Rist) walks on the sidewalk, smashing the windows of cars. The video is about a “creative divergence”, so to speak. It was meant to express and visualize Rist’s anger towards her editor, who wouldn’t let her do the things she wished to do, even though he had apparently given her carte blanche. She felt like smashing his car, but instead chose to make a video, which challenged and even altered her aggression: “That was my catharsis”, she said in an interview. At the same time, the act of vandalizing cars was meant to question the very idea of personal mobility, the car as an extension of the self, the normalization of technology: “How we get used to something very quickly”, she added. In Understanding Media, MccLuhan famously called the car a carapace, “the protective and aggressive shell, of urban and suburban man”. In the video, Rist’s actions have no consequences. A policewoman, closely following her, does not intervene. In Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog III, a man wearing a suit and sneakers is running through the streets of a quintessential American city, carrying a bouquet of flowers which he uses to shatter the windows of various vehicles parked on the sidewalk. As somebody who lived in Milan for many years, the abominable image of cars parked on sidewalks is so common that the locals do not even notice, let alone complain, anymore. There’s a quintessential Milanese urban ugliness that has to do with the ubiquitous presence of cars. Do you believe that car vandalism can be considered a form of performance art? Or is vandalism legitimate only as a symbolic gesture within a fictional space? In the accompanying text, you write that the main character’s “surprising actions… remain without consequence in virtuality.” Are you suggesting that the “magic circle” of the artworld prevents any consequences to affect the real world, in the same way that Rist’s actions in her video are not sanctioned as a criminal act?

Sebastian Blank: I hear from your question that you also have strong emotions towards cars. Would you like to hear some kind of legitimacy for car vandalism from me? Unfortunately, I cannot provide it. I have seen that you have also worked on the subject of cars, artistically. Subversive methods, such as art, would always be my preference over vandalism. If that doesn't help, we’ll see...

Speaking of subversiveness there’s another twist: Part Three is also a quotation of Robert Gordon McHarg III’s work HIM, in which he exhibits and photographs a life-size wax figure of Charles Saatchi in various disguises. It is his face that the walking man is wearing, whether as a mask or whether it is actually him remains unclear – there are various possibilities of interpretation. How would Saatchi act in my world? Is he actually doing the performance and if so what would be the metaphorical meaning to how we explain the vandalism?

In Rist’s original work, the smashing of car windows is real, but also not real, because it’s staged. This becomes apparent to the viewer when the expected reaction of the policewoman fails to occur. Then, what we see is a fantasy concocted by Rist. Nevertheless, the performance is inspiring and thought-provoking, because it irritates and perhaps leads to change at some point. Art can provide criticism and ideas, but as I already wrote at that time: If society wants to improve, it must do so itself. For me personally discourse is always interesting. I have come to the realization that, with regard to the car, I must have experienced a similar catharsis through Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog as Rist did with her performance. At least as far as I recall I haven’t played any serious car games after finishing this piece.

Matteo Bittanti: Yes, I do viscerally despise the car-fossil fuel-industrial complex, but no, I’m not promoting car vandalism, although I have the uttermost respect for Andreas Malm’s ideas. Are you then suggesting that art and games are similar insofar they both provide a space for experimentation and even insubordination that do carry serious consequences in real life, and therefore are ultimately harmless to the powers that be? As Marshall McLuhan wrote in Understanding Media, “Art, like games, is a translator of experience. What we have already felt or seen in one situation we are suddenly given in a new kind of material. Games, likewise, shift familiar experience into new forms, giving the bleak and the bright side of things sudden luminosity”. What is your take on digital games as spaces for artistic performance, nowadays? Have you ever considered using them to reenact other artistic performances?

Sebastian Blank: Games actually have the advantage of providing a space for experimentation and also for disobedience. However, due to the fact that nowadays we are predominantly talking about multiplayer games, I no longer necessarily see this space as a protected one, because experiments there involve real people. One of the most influential performances I have seen being made with games is the performance within Counter-Strike, Freedom, in which Eva & Franco Mattes rightfully insisted on the freedom of art. They did not want to be part of the war in a war game which hurt the feelings of the other gamers involved. This wasn’t nice but it was necessary to make their frightening views and questionable actions visible in the first place. The “bright” in this case being the togetherness of the group of players and the “bleak” their dubious views and brutal reaction to the artists. Through their interactivity, games nowadays offer different opportunities for experiments and performances than a decade ago, which I find interesting. As for your second question, I think re-enactments of real performances often rely on the question of relevance (digital vs. real). Because that is not primarily my focus I probably wouldn’t re-enact real-life performances unless they fit my artistic intent otherwise.

Matteo Bittanti: Grand Theft Auto recurs in another project of yours, ...the way that even I would buy (2007). What does Grand Art TheftⓇ refer to?

Sebastian Blank: Grand Art TheftⓇ is a commercially successful game, that people play in my world and is available on all major platforms. The goal is to become a master thief and to rule the city as head of a criminal syndication, specialized in art theft.

Kunst und Gesellschaft im Dialog I-III

Digital video (787 x 576), color, sound, 13’ 51” (part I: 6’ 02”; part II: 4’ 17”, part III: 3’ 33”), 2009, Germany

Created by Sebastian Blank, 2009

Courtesy of Sebastian Blank, 2022