THE BLUE SEALS. EXTINCT AND HAPPY

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 5’ 25”, Germany, 2023

Created by Moritz Jekat

WORLD PREMIERE

In The Blue Seals. Extinct and Happy the artist tackles the multifaceted theme of memory and its impact on our sense of place and identity. Exploring the notion of “home” as a deeply personal and evolving construct, the artist delves into their relationship with the city of Berlin, a metropolis which has undergone significant transformation over the past decade. Through the medium of an immersive bus simulation game set in 2021 Berlin, the artist takes us on a virtual journey through the city’s ever-changing landscape, one that mirrors the shifts and fluxes of their own being. The work weaves together a complex interplay of past and present, real and imagined, personal and collective, as the artist reflects on their fading memories of a love that once bloomed amid the streets of Berlin. The Blue Seals is an evocative exploration of the ways in which we are shaped by the spaces we inhabit and the memories we carry within us.

Moritz Jekat is a visual artist hailing from the vibrant intersection of Berlin and Lausanne, whose practice spans the mediums of computer-generated imagery, sculpture, and installation. With a distinguished BA in Visual Communication from Potsdam under their belt, Jekat has since gone on to further refine his craft as a participant in the esteemed Master program of Photography at ECAL in Renens, Switzerland. At the core of Jekat’s practice lies an incisive exploration of contemporary developments within western and specifically German society, with a particular emphasis on the role of identity and digital culture. Investigating the themes of co-existence, cohabitation, and the multiplicity of ideas that converge in shared spaces, Jekat’s work often draws on his own immediate surroundings before expanding outward to explore broader universal truths. Jekat explores the intersections between human experience and technological advancement, with computer-generated imagery and the use of AI serving as powerful tools in his artistic arsenal. Their work stands out as a thoughtful, insightful exploration of the rapidly evolving landscape of modern life, reflecting a deep engagement with the pressing questions and issues of our time.

Matteo Bittanti: Your personal connection to the medium of video games is a topic that deeply intrigues me. Specifically, I would love to learn more about your encounter with the particular simulation that serves as the foundation of your recent video art project. What drew you to The Bus, and how did you recognize its potential as a rich site for artistic exploration? As you developed your project, I imagine that there were a range of creative and technical considerations that came into play. We would be fascinated to hear more about your process and approach, and how you navigated the unique challenges and opportunities presented by this medium. Could you walk us through some of the key decisions and strategies that informed your work?

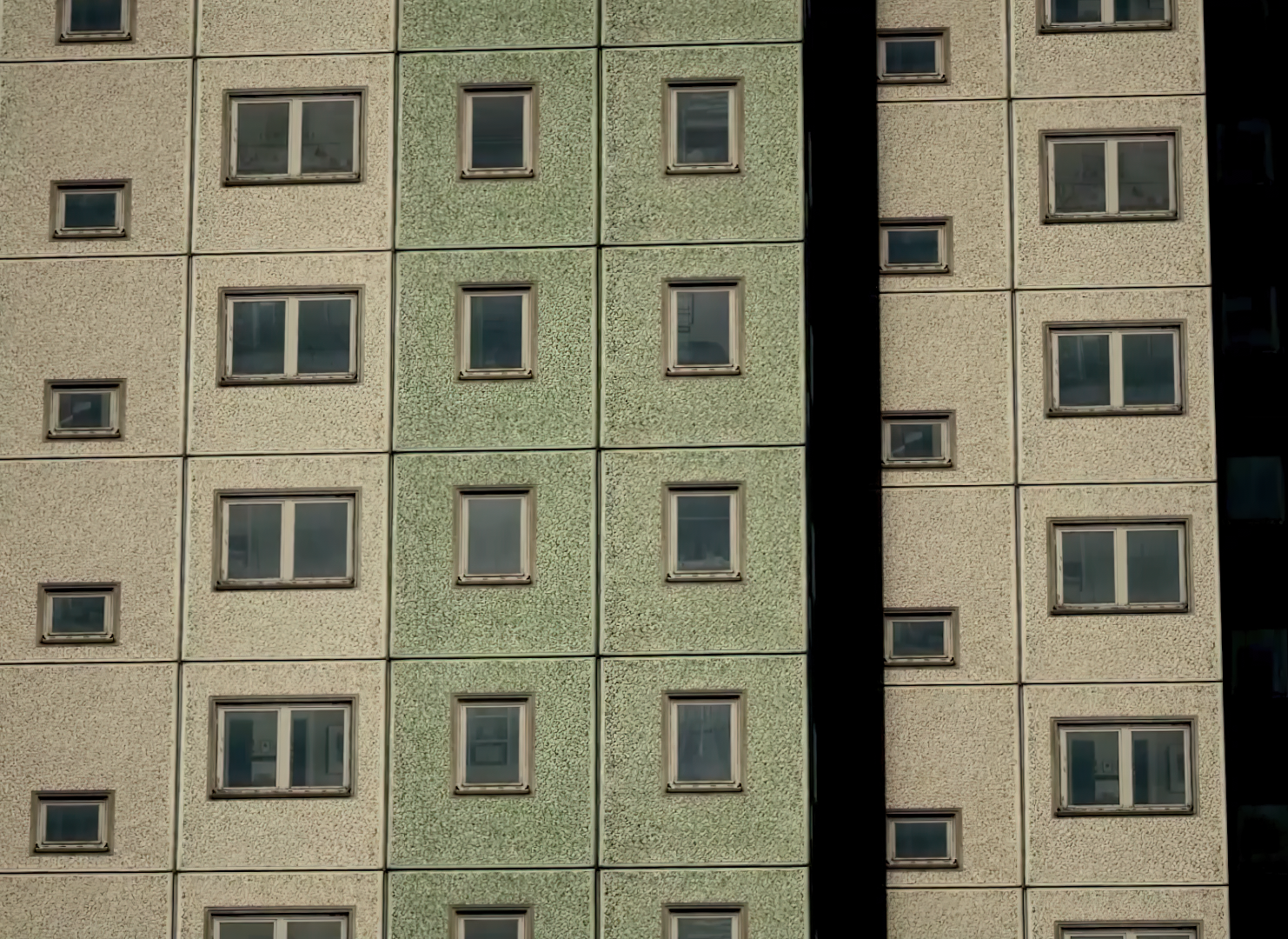

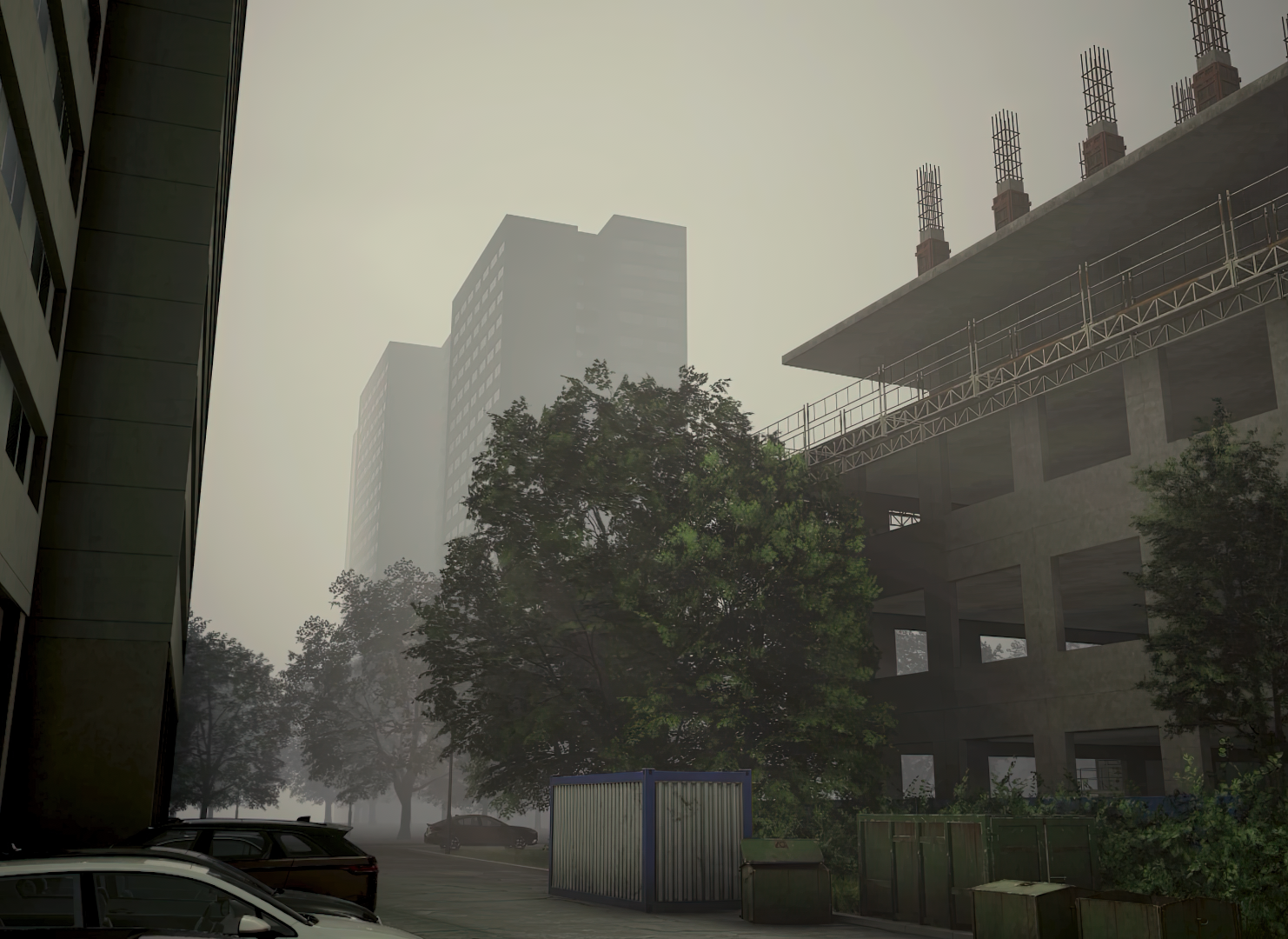

Moritz Jekat: For me, a bus driving simulation was a truly new world. The last “driving-simulation” I played was Microsoft Flight simulator 98 as one of my early modern computer games on my first Windows-based personal computer, which replaced my previous machine, a Commodore 64. As I embarked upon the creation of The Blue Seals, my primary objective was to conceive a work that would be situated in modern-day Berlin. Though I was living and studying in Switzerland during the inception of the project, it was in Berlin – the place I deem my true home and where I feel complete – that my heart lay. I simply missed my home, while going through a quite drastic transition in the relationship with my partner at the same time. I was simply craving comfort and wanted to go home at a time where that was physically impossible for me. I began looking for video games set in Berlin. For the most part, I could only find simulations of historical Berlin within the context of World War II or the Cold War. But then I stumbled upon The Bus. Set in 2021, it provides a truly accurate reconstruction of some major parts of the city, as well some parts which are close to where I used to live for a long time, delivered with decent graphics. Driving around Berlin in The Bus strangely made me feel home. I felt reminded of the time when I started exploring real life Berlin with my camera between 2012-13. As I was tinkering with the game, I accidentally ended up “behind the scenes” so to speak: I managed to spawn myself over the borders of the assigned game level and found a partly constructed/deconstructed image of Berlin. Still recognizable as what it should picture, as what it was, as what it might become, but deconstructed. This mix of an almost perfect reconstruction of 2021 Berlin and a dissected and fading Berlin was somehow aligned to the thoughts, feelings and memories I was experiencing at the time. I first started to follow the path of a music video I encountered in my early Berlin years, which featured a 1991 tram ride through east Berlin to Berlin Mitte.

Fascinated by the accuracy as well as the obvious recognizable change of certain parts of the game city and its relation to real life Berlin’s transformation, I decided to follow my own paths and memories within this virtual space. Just like real life Berlin is transforming rapidly and went through multiple faces since my move there about ten years ago – and, of course, before –, I personally experienced a multiplicity of selves since then. What were these faces? What are these memories and which spaces do they relate to? What did I do and what do I feel about this? The voice you hear tells memory fragments from different timelines enmeshed in a new story, which is as real as those memories. For this process, I used associative writing techniques which I later edited into the final text. With this story and memories in mind, I wandered through the streets of The Bus Berlin. I went on virtual daytime, morning, evening and nighttime strolls in Summer, Winter, Spring and Autumn around the spaces connected to my memories. Listening to music and drinking beer.

Many of those places were not constructed fully yet. Just like my memories, like my transitioning self, like my thoughts and feelings they were fragmented. I recorded hours of gameplay. Actually ended up walking the city instead of driving as you could leave the bus, which allowed me access to spaces beyond the streets. The music you hear in The Blue Seals is AI generated, based on the sound from the music video I mentioned earlier. Just like my memories, just like this virtual Berlin, it is rather a weird idea and image of the real life version of itself, sometimes close, sometimes far.

Matteo Bittanti: Prior to creating The Blue Seals, were you already well-versed in the medium of machinima and in-game photography? Did you approach this project as a one-time endeavor, or do you envision continued engagement with the medium in your artistic practice? Reflecting on your experience, what insights did you glean about the possibilities and limitations of using video games as a creative medium, and how did this process challenge and inform your artistic practice moving forward?

Moritz Jekat: There was an awareness of machinima and in-game photography before, but my interest in testing it for my own work was strongly motivated by the teaching of Marco de Mutiis during a Master Class at ECAL, which focused on the phenomenon of the gamification of photography.

My previous practice includes plenty of CGI and as well as game engines like Unreal to create video-based projects. I use the game engine more like a photo studio in which I can create work environments, avatars, and objects which then become actors in a video. With The Blue Seals, the process was different. It was my first time filming inside a game and connecting the concept underlying the project to an idea. It reminded me a lot of my artistic origin in documentary photography, while it adds a whole different level of possibilities.

In my early years as an artist, I was fascinated about photography allowing you access to places, people and their thoughts and feelings, which you might not be as easily able to encounter without a camera. A game can expand this possibility even further. You can photograph at any time as long as you have a working computer. You can play with a level of abstraction that might be harder or impossible to find IRL. You can go places and times that you physically wouldn’t be able to enter. You can take perspectives that are inaccessible IRL. The reflection of real human emotion and expression in a game like The Bus is obviously not comparable to those of real humans yet. Although there are most likely better examples for images of human bodies, expression and feelings in other games, I suppose. Of course, they lack materiality. There are no objects and surfaces that I can touch, nor smell. You can merely explore faces and spaces on a purely audiovisual and emotional level. Nevertheless this game allowed me to express my very personal thoughts, feelings and memories connected to a place and time that I was not able to reach in real life in that moment of my life. Immersive as the game city is, I still was able to recall certain smells and physical experiences. I can say that I love the amalgam created by my artistic experience as a photographer and visual artist brought together with the possibilities that a game like The Bus provided. Since the virtual spheres have been very present in my work for a few years now, I very much see myself further implementing and developing this type of creation within my practice.

Matteo Bittanti: In The Blue Seals, the memories generated through gameplay are real in the sense that they are anchored to a specific time and virtual space, yet remain intangible. How did you navigate the boundary between fact and fiction in the creation of this work, and to what extent did you rely on the affordances of the medium to construct a highly fictionalized past? Did you draw from elements of autofiction, or did you craft an entirely new narrative within the context of the game world? Ultimately, what insights do you believe can be gained by exploring the malleability and subjectivity of memory within the realm of video games?

Moritz Jekat: I think that all our memories are some sort of fiction. No memory is fully accurate. Of course some of our memories relate to real people, objects, and spaces we can go back to and which we can touch, smell, hear or similar. But even those real life connections do not allow us to construct a fully non-fictional memory. We are not even able to create a 100% accurate image of the physical, so-called “real world” around us in the now: photography certainly doesn’t. Our senses, our chemistry, hormones, cognitive processes, social context and emotions create the image of the reality around us and so they do create the images of our memories. None of these are fully “real”. It is always a matter of perspective, a matter of context, a matter of experience and circumstances. A century ago people might have used a black and white photograph to create and deal with memory. Before that it was text, paintings, drawings or objects. This is equally real or tangible, or fictional and intangible, as a memory and image I create within or through a computer game or virtual space.

The memories and emotions that I experienced while in the game were very real for me personally. All the versions of myself I came across were real for me at one point. Though they are not fully real anymore. They are an idea of something that has happened in the past and that I triggered and now pictures and phrases through this virtual space, computer game Berlin. This is also how I see the simulation of Berlin in The Bus. As dramatically fast real life Berlin changes it as well is simply an imagination. Every time I come back to IRL Berlin it has changed. So my image of it is not real anymore. Which is why IRL Berlin can be seen as somewhat a fiction by itself.

The memories I scripted around and used for The Blue Seals are an amalgam of multiple past events. Different temporaries of myself and of a city enmeshed in a new (slightly absurd) narrative which is then embedded in a frozen image of 2021 Berlin a group of people created for The Bus. A present creation of my past within a virtual simulation of others. A coming together of multiple peoples ideas and images within a virtual space. Though this is autobiographical. And very personal. And non-linear. Like our minds and the world around us. And like any other memory it is more or less a fiction. The fact that it is created in a computer game doesn’t change that in either direction. It might only change the aesthetics and visuals of it. Some places of IRL Berlin simply do not exist in The Bus at all. Neukölln for example, where I last lived before going to Switzerland, is located on the end of the game map. It is an empty space on a plane which looks like the typical Unreal engine grid. Its inaccessibility within the game led me to connect some of those younger memories of mine to older versions of myself that for example lived in Kreuzberg or Friedrichshain, which are partly accessible in the game. In relation with the images this might draw elements from what is called autofiction.

Shaping and picturing memory within a computer game is – even though it offers things that are impossible IRL – not extremely different to doing so in IRL, like I would for example do with my camera. I am not physically present and still experience and form emotional memory experiences comparable to those created IRL. This allows us a fascinating shift in the point of view on “real life” and “real time” and our experiences within it.

Matteo Bittanti: Perhaps first and foremost, games and digital technologies offer an endless opportunity for role play and performance. These tools, which are also environments, allow us to continuously redefine our identity, and retell the story of who we are, where we come from and what we desire. How crucial is this ongoing process of self-storytelling which shapes our experiences within and beyond the digital realm in your practice as an artist?

Moritz Jekat: As I was first working very strictly as a photo artist with strong ties to documentary photography I was more observing and in bits and pieces commenting. First when I started exploring my very close and personal environment, including my very private life, I started to open up my point of view with self-portraits and have other people taking pictures of me.

Though a performative aspect for me lies not only in performance with a body or face or performance communicated through images. Role play and performance are as well to be associated with twisting purposes, to occupy, to trade, to exchange. When I work with other artists in collaborations or a collective, everything we do is or can become some sort of role play and performance. You play with new roles within a group, you perform ideas and thoughts in a real life or virtual experiment. You might repurpose a certain space that has been assigned to you with something unexpected. You could occupy an object or aesthetic, you can appropriate. You redefine yourself and your identity within a group. you can dissect what surrounds us and what as well shapes us. Enmesh. Dissolve. Evolve. All these are performative aspects that are happening IRL everyday if you allow so just as they happen in the virtual spheres. I want to believe that this happens in my work too, especially within the collaborative and collective works I have started to explore.

Matteo Bittanti: In your artistic practice, the concept of “home” takes center stage, particularly in your recent work The Blue Seals. How do digital environments facilitate a sense of domesticity and belonging, or are they merely Marc Augé’s “non-spaces” of transition and displacement? Through your exploration of the constantly evolving cityscape of Berlin, what insights do you gain about the intersections of identity, memory, and the spaces we occupy within the digital realm?

Moritz Jekat: I never really felt to belong where I grew up, though this small village in the West German countryside is still one of my “past homes” based on all the memories I have with this space and the emotions connected. After drifting around in Europe and the world from 19 till 24 I first relocated to Berlin over ten years ago the feeling of belonging was immediately there, even though the home in a traditional way wasn’t present yet. Though this new place became home to me very quickly. I see this connected with feelings, ways of thinking, memories and experience we have alone or as a collective. Lived experience and new memories in a real space can grow. This is equally possible in a virtual space. Our identity is shaped out of individual memories, lived experience, emotions, our bodies and desires, the people and spaces surrounding us, their experiences and feelings and how they mirror us and much more. Obviously identity is something fluid and not set in stone, that changes slowly with the spaces and people surrounding it changing. Identity, memory and spaces are tight knit and intertwined and always connected. So they are digital.

I have plenty of video game related memories from my childhood. I still recall maps from 007 James Bond’s GoldenEye, Super Mario Smash Bros, Need for Speed or Pokémon from my friend’s Nintendo 64 on which we played together and drove our parents nuts as a group of teenagers occupying the living room TVs during school holidays for weeks. I have vibrant memories inside and outside those games. To have played these inside the space that we considered our home back then plays a role in this: belonging, home, memory and identity all together. It was part of my identity back then, is a memory now and part of a past version of myself, though my identity is a different one than when I was 10 or 12 years old.

These virtual game spaces we inhabit are built to entertain and eventually keep you for as long as possible – commercially motivated – or simply bridge “waiting moments” IRL. This very much relates to the notion of “non-spaces”. Based on my childhood memory of gaming and my experience in the virtual as a grown person I want to think of virtual spaces, no matter if in computer games or simply the internet, as more than that. Though not every single virtual space might achieve this: There are for sure “non-spaces” in the virtual as there are IRL. Real life and the virtual are connected and somewhat distorted mirrors of each other, so of course I find “non-spaces“ in both and as well spaces that facilitate a sense of home and belonging. Video games carry their own culture, memories and identity or at least relate to those in real life. Some of them are more or better than others. “Non-spaces” in a computer game could be the game menu or in between “missions”.

In my exploration of The Bus I actually escaped the real game purpose, i.e., driving buses through Berlin, following the bus lines, collecting passengers and bringing them from point A to point B without crashing your bus. I left the bus and started walking around. A bus driver on pause mode walking through the city. I basically inhabited what is created as a “non-space” and found feelings of belonging and associations of home here. The city I experienced, the spaces I looked at and as well the deconstructed spaces behind the official game map, triggered these feelings. I think I would possibly get bored and feel very lonely at some point if I would continue this game for much longer. Cause in the end the space there and the interactions are limited. But the memories and feelings I carry with me, which are part of my identity, that I brought to this virtual space that in the way it looks, sounds and moves as well carries its own memory and identity creates an amalgam of belonging and home. In this case my life and past in Berlin is part of my now identity. The feeling within this space is similar no matter if IRL or in-game.

Matteo Bittanti: I am extremely interested in the relationship between The Blue Seals and your previous project, Metaverse can you eat me (2022). The trait d’union or common denominator between two projects focusing on the interplay between the real and imagined, identity and projection, is the use of an avatar (a surrogate puppet, in the latter) as a placeholder or stand-in for the artist. Did you intend to create a thematic link between the two projects, or was it a natural progression of your artistic exploration?

Moritz Jekat: This was largely unintentionally. The two works emerged within a year: Metaverse can you eat me was made in mid 2022 and The Blue Seals in early 2023. Similar feelings and thoughts were present: questioning the notion of the real, our perception of it and the debate around identity have played a central role within my practice for a while. Both projects talk about very personal feelings and reveal – albeit cryptically – very personal thoughts. The way I scripted the spoken parts for both projects were quite similar. I started with associative writing and a dream journal and then directed the ideas into a more specific direction. Both are as well serving my very own need for healing and comfort and the attempt to reconnect: The projection of my personal emotional inside on to an avatar in an attempt to understand myself better and reconnect with myself, and the coming together of memories of love relationships with a virtual space as a placeholder for the real life space where this took place. It is this bizarre absurdity of our system and world: We are in the fastest, technically and globally best connected moment in humankind history, yet we are disconnected from each other and often even from yourself. I am using the virtual spaces on my hands to explore lived human emotions and deal with connectivity that is out of reach at certain moments of our real lives. In Metaverse can you eat me and The Blue Seals this happens on a very individual level, while in a collective project I am involved in, ReKin, a group of ten artists experimenting with this on a co-individual level.

Matteo Bittanti: In the spirit of New Mythologies (2021-2022), your inquiry about the work is an invitation to explore the subjective and ever-changing landscape of meaning-making. While the ludic references of Rubik’s cube, swords, and lore may offer an entry point, the work's ultimate significance remains somewhat enigmatic. Can you walk us through your creative process and the conceptual framework behind this multifaceted project?

Moritz Jekat: New Mythologies is one part of the title. The full title is Family portraits, sibling 01, 2021 – New Mythologies. The creation of the work stemmed from a sense of detachment and a lack of comprehension. I have a sibling whose political beliefs have become enigmatic and no longer resonate with me. Despite our shared memories and upbringing in the same environment, I find myself puzzled by the divide between us. It makes me wonder about the factors that shape our ideas and perceptions of reality, leading us to drift apart in this manner. Nonetheless, I still cherish my sibling and our shared history.

In a series of visits and interviews I tried to understand the different bubbles I was confronted with. Documenting the personal space, I found certain objects that were in my point of view very specific for my sibling’s persona and thinking. In relation to the main source of my family-members political information, the virtual spaces, I related these private real life objects from my siblings space with objects I found online. 3D-scans of real life objects are put in context with 3D-assets found on online platforms. Just like certain thoughts and ideas these 3D-assets are mixed within the real life 3D-scans. A coming together of different truths. A rearrangement of realities in a virtual space. All of this is implemented in a soundscape generated by an AI which was fed with text message conversations from the political bubble I found my sibling in. Placed in a blue space in relation to the blue color a computer screen displays, when confronted with an error.

This work plays as well with the notion of identity, family and home, but mainly with the perception of reality and the formation of ideas nowadays. Compared to Metaverse can you eat me and The Blue Seals this work still follows strong patterns from my documentary photography origin and works more analytical, rational and observing than the works talked about earlier.

Matteo Bittanti: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Moritz Jekat: I want to thank Marco de Mutiis for his very inspiring support and feedback during the run of my studies at ECAL, which had a great impact on my work and in the creation of my work The Blue Seals.

THE BLUE SEALS. EXTINCT AND HAPPY

machinima/digital video (1482 x 1080), color, sound, 5’ 20”, Germany, 2023

Created by Moritz Jekat, 2023

Courtesy of Moritz Jekat, 2023

Made with The Bus (TML Studios, 2021)