36,000 FEET

Digital video, color, sound, 7’36”, 2021, Switzerland

Created by Matthieu Cherubini

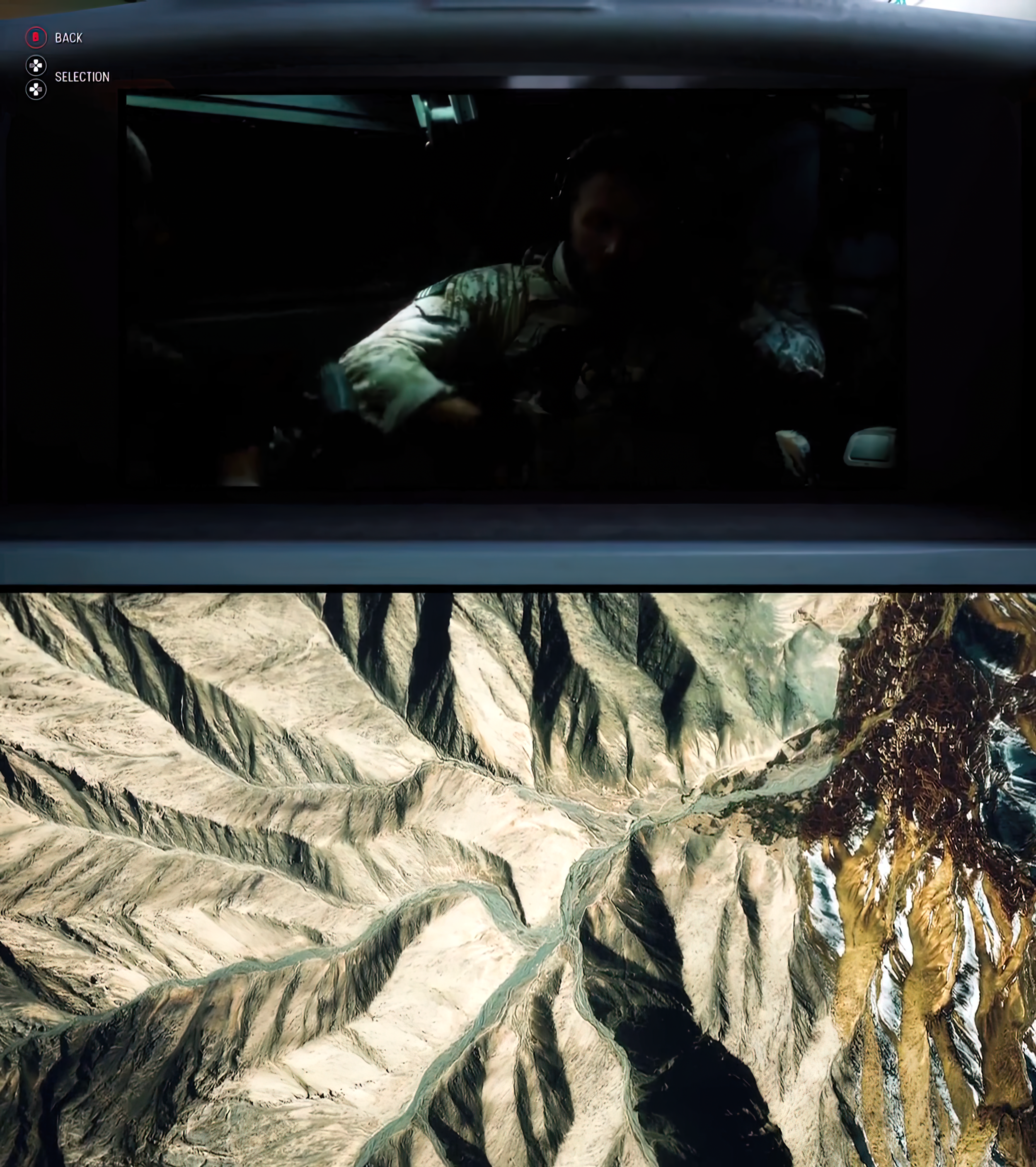

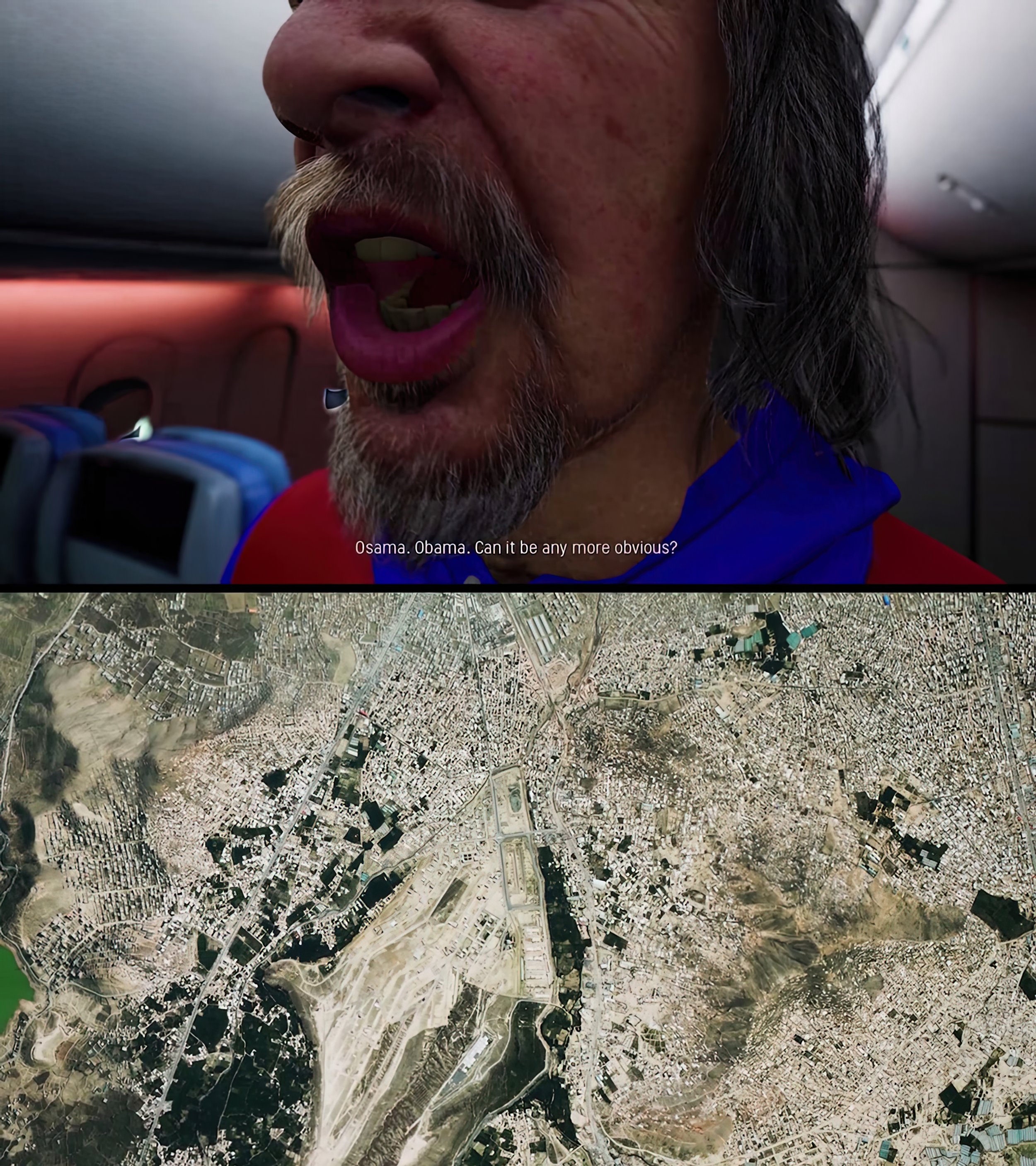

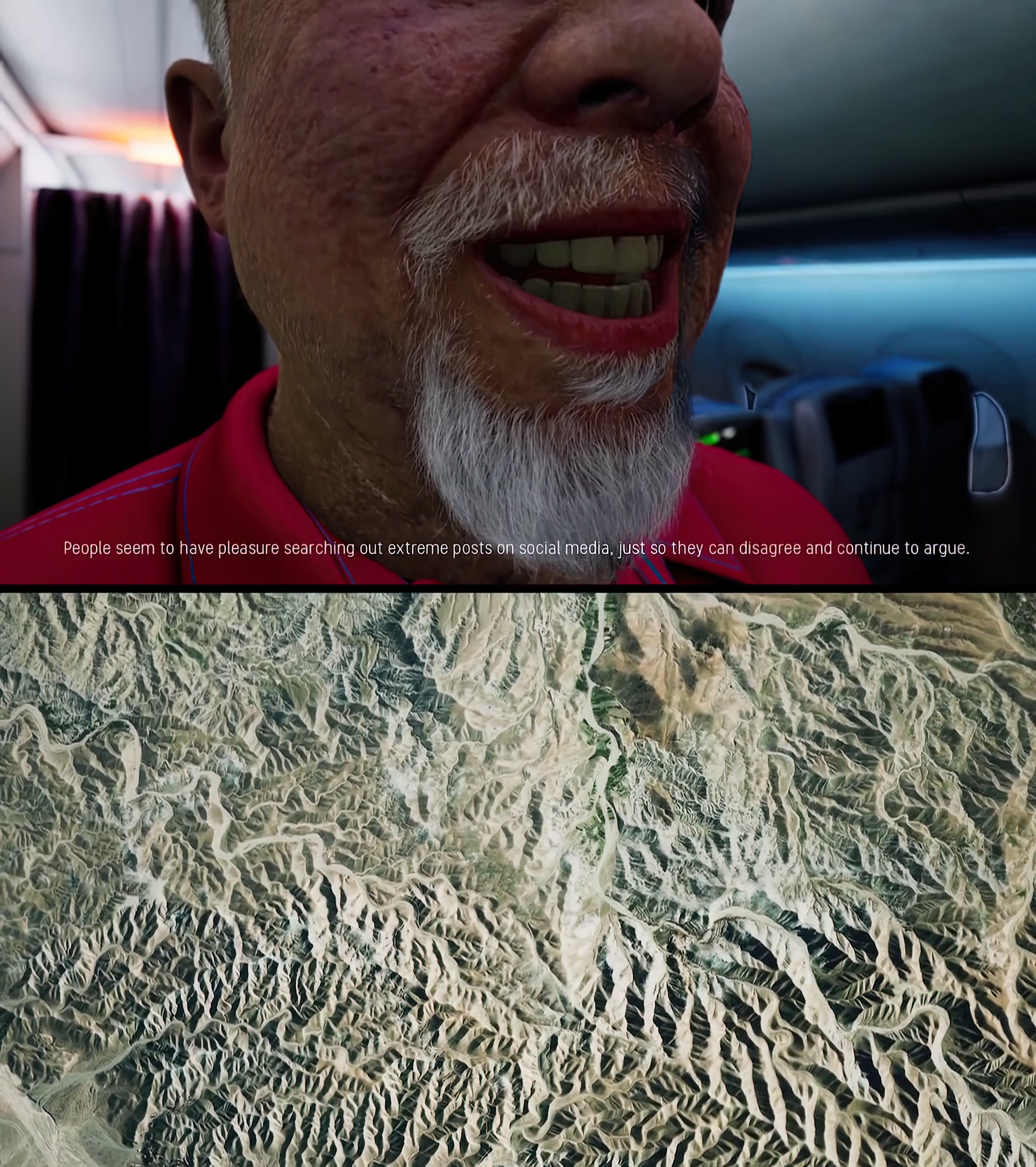

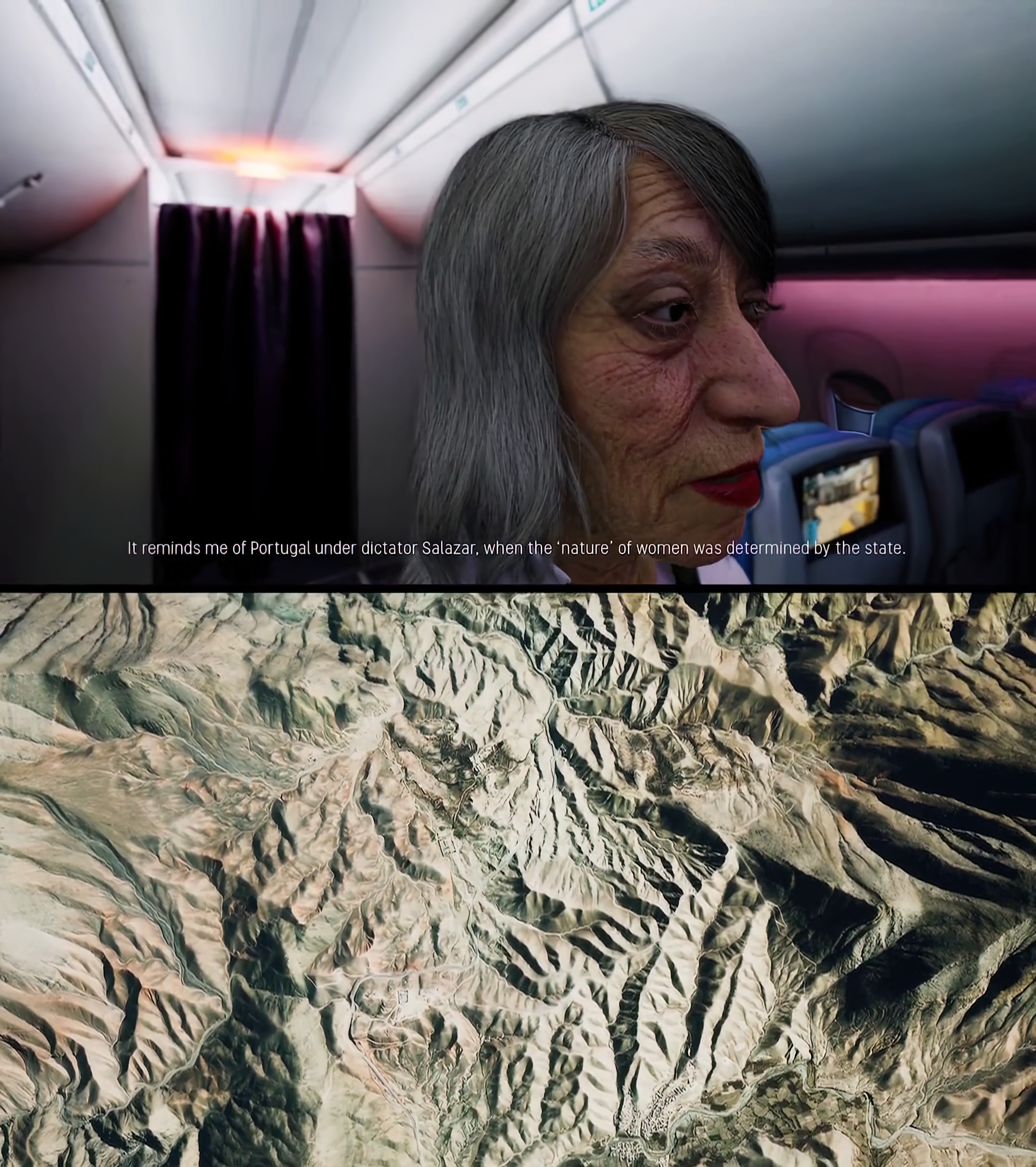

36,000 feet is a video game set aboard a commercial plane flying over Afghanistan. As a passenger returning to his country from a holiday abroad, the player can watch blockbuster movies such as American Sniper on his in-flight entertainment display or chat with other passengers. The topics of their conversations range from terrorism to the “end of France”, whether Obama is Osama and how the West is currently living under a “terrible dictatorship”. 36,000 feet was developed with Unreal Engine 4, MetaHumans and Blender. This single channel video showcases some salient conversations and is meant as a standalone piece.

Matthieu Cherubini is a Swiss designer. After studying software engineering and media art/design, between 2012-2015, Cherubini joined a Doctorate program in the Design Interactions department at the Royal College of Art. His research examines the implications of artificial moral agents on mundane events and everyday lives, both today and in the near future. His projects have been exhibited at several international venues, including the Centre Pompidou (France), ZKM (Germany), the V&A Museum (United Kingdom), the Vitra Design Museum (Germany), the Mori Art Museum (Japan), the House of Electronic Arts (Switzerland), and the Nam June Paik Art Center (South Korea). Cherubini is currently working and living in Beijing, China.

Matteo Bittanti: You were one of the first students to graduate from the groundbreaking Media Design program at HEAD, in Geneva. Can you describe your experience? How did your studies in software, engineering, media, and interaction design contribute to your critical understanding of design and technology?

Matthieu Cherubini: Yes, I was part of the first batch, a bit more than ten years ago. It was indeed an interesting program for someone like me who knew almost nothing about design and art. The program was relatively broad and we were exposed to many different practices pertinent to this field, ranging from speculative design to generative art and game design. It is there that I was introduced to artists like UBERMORGEN and designers such as Auger-Loizeau. It’s important to me to mention that these two collectives had a huge influence on me. Even as I look at all their projects today, everything they did was always so timely: they did the right thing at the right time. It is people like these that helped me to see how engineering methods could be used to create projects that can foster critical thinking about the effects of technology. Software engineering allowed me to learn the hard skills I needed to create my own things and to understand the possibilities and limits of the system, while media art/design introduced me to new types of people who think in a very different, critical way about these technologies.

Matteo Bittanti: You subsequently left Switzerland and earned a PhD in Design Interactions at the Royal College of Art in London. What was the most remarkable learning experience for you in the United Kingdom?

Matthieu Cherubini: I actually didn’t earn a Doctorate as I left after three years when the department closed down in 2015. Nonetheless, being under the supervision of designers such as James Auger and Dunne & Raby was a great learning experience. As I mentioned above, I admire the way they critically think about potential issues caused by new technologies and how they are able to translate such thinking into a concrete project and in a very precise way. To be surrounded by such people really pushes you to think in a different way and to look at issues from multiple perspectives. This is valuable not only for work but also for daily life.

Matteo Bittanti: How would you describe the relationship between your previous project 35,000 feet (2017) and 36,000 feet (2021)? What kind of technical challenges did you encounter in the production of the latter? I noticed that you switched from Unity 3D to the Unreal Engine…

Matthieu Cherubini: I would say that 36,000 Feet is the version that I wanted to make initially but was unable to, as my 3D skills and rendering abilities were completely horrible at that time. In the previous version, I tried to show in a different way what is now shown via the interactions with other passengers. For example, the discussion with Philibert, the artist, was previously shown as a tweet that you could send from the in-flight infotainment system. I didn’t encounter any specific technical challenges while developing this new version. On the contrary, I would say I’m very amazed at how these game-related technologies are becoming more and more accessible and easy to use for almost no cost.

Matteo Bittanti: Are you familiar with Bacronym’s Airplane Mode? Do you know if the developers were aware of your project, 35,000 feet?

Matthieu Cherubini: No, I never heard about it before. But there are some interesting affinities between the two projects.

Matteo Bittanti: The vast majority of flight simulators emphasize the landscape, which they reproduce with increasingly aesthetic fidelity and photo realistic accuracy. 36,000 feet, on the other hand, feels more like a rant simulator — and I mean this as a compliment — the player walks around in the cabin listening to the passengers’ monologues about terrorism, politics, and culture wars or watch mind numbing flicks under the aegis of “in-flight entertainment”, completely unaware of their surroundings, geographically speaking. Is the deliberate lack of interactivity a metaphor for the simultaneous isolation and polarization of many western societies, where citizens increasingly inhabit different socio-cultural realities, trapped in their own filter bubbles, unable to connect?

Matthieu Cherubini: Actually, a rant simulator is a nice way to describe the project. However, I don’t think the lack of interactivity was meant for that, or I didn’t think that far about it. Actually, the project’s theme is fairly simple: the plane flying over a country torn by war is just a metaphor of most of us being in our own bubble, completely disconnected from what is happening around us, myself included. All the passengers on that plane, everybody seems to care or to have an opinion about a specific topic and yet, they are completely detached from it. Likewise, we care about everything without really caring about anything. People are tweeting about Black Lives Matter and one second later retweet about the latest clip of a video by Justin Bieber; Greta Thunberg is traveling on a zero-carbon emission boat but then needs to return to the same boat as well as the supporting crew by plane… And this is celebrated… I might be stupid but none of it makes sense for me.

Matteo Bittanti: I share your befuddlement. Did you design the characters based on existing personalities? I am especially interested in Philbert, the clueless conceptual artist from Brittany whose main artistic output seems to be white privilege. Hearing about his latest project about the plight of Afghanistan women reminded me of so much “culturally sensitive art” produced in the West meant to “provoke meaningful change”…

Matthieu Cherubini: Yes, all personalities are caricatures of people we might have encountered before. I’m glad that you are also interested in Philibert and seem to dislike him as much as I do. He was the first character I made. Unfortunately, he is the caricature of the majority of the people I saw in the art and design world in the past decade. I usually avoid calling myself an artist because I want to have as little to do with this scene as possible. To me, it looks like a huge circus. How can you take seriously someone who is making artworks about drone attacks but lived all his life in a comfy loft in London? Or an art curator who is curating an exhibition about “social justice” but is demanding a first class plane ticket to attend the exhibition’s opening? If you want to provoke meaningful change, do a humanitarian mission, not an art project. Most of the works and discussions I see recently from this field are mere variations of the same topics: social awareness, feminism, environmentalism, etc… This “woke” culture is not simply boring as some say, but actually very dangerous. All these crucial topics get dumbed down and reduced to worthless actions that hold nothing behind them. People cannot take this kind idiotic argumentation over and over again. Instead of helping to create “meaningful changes”, they are actively discrediting the significance of the issues they tackle in such a pedestrian, hypocritical way.

Matteo Bittanti: This reminds me of Kaouther Ben Hania’s The Man Who Sold His Skin. Have you seen this movie, by any chance? What’s your take?

Matthieu Cherubini: What I cannot stand is the lack of consistency between the discourse, the artwork, and the person producing the artwork. In the movie, the artist who is using the Syrian refugee is openly cynical and admits to using this human being as an object. He doesn’t make a speech that his project aims to bring social awareness about Syrian refugees, the Syria war, or something like this. If this was a real art project, I would probably be interested in it. Although they have a very different discourse, it somehow reminds me of some of Santiago Sierra’s works, for example, 160 cm Line Tattooed on 4 People, where he tattooed a line across the back of four sex workers who are addicted to heroin. He then remunerated them with a certain amount of money which was equal to the price of a single shot of heroin. It is very brutal and ethically very questionable, but I like what he is doing because his discourse and his work have always been very consistent through his career. For me, art is the only place where I can appreciate something without morally agreeing with it. But as blatant as it sounds, that’s maybe partly the point of it.

Matteo Bittanti: Indeed. As you know, The Man Who Sold His Skin is inspired by the work of Belgian neo-conceptualist artist Wim Delvoye, who makes a cameo. Going back to 36,000 feet, were there additional characters that you wanted to include but ultimately didn’t, due to time or technical constraints, or even a change of heart?

Matthieu Cherubini: That’s all the characters I had in mind, but I had to write a few iterations of the dialogues so their personality and discourse changed a little bit over time. It was the most difficult part of the project for me as I’m not that good at writing. It is difficult to make a caricature, it has to be subtle. It has to be grotesque but without exaggerating… I don’t know if I was able to accomplish what I wanted to achieve but that is what I was aiming for.

Matteo Bittanti: The United States has systematically lost every major conflict since WWII, culminating with the recent debacle in Afghanistan, which echoed a similar dramatic endgame in Vietnam. At the same time, the US is able to project an image of omnipotence through their extraordinary marketing machine, which — in your video game — is directly referenced by the in-flight entertainment options, featuring such blockbuster movie as American Sniper, Zero Dark Thirty and other examples of highly remunerative examples of propaganda. This theme was also present in 35,000 feet). Does IRL military setbacks matter when you are always winning in virtual reality?

Matthieu Cherubini: As a Swiss citizen, my military experience is limited to video games, movies, and my six-month mandatory military service. Therefore, I would feel very uncomfortable commenting on any military actions conducted by other countries. Besides, I would probably have nothing interesting to say about it, as such topics are extremely complex. It happened that my projects such as 36,000 Feet or Afghan War Diary were mistakenly taken as a criticism towards the US or the entertainment industry. But it is not the case at all: my main focus in these projects is myself and people alike and how we tend to consume such topics for our own entertainment. A guilty pleasure, somehow.

Matteo Bittanti: The political views of the characters that the player “meets” onboard are relatively clear. But who is the main player, so to speak? The first person perspective makes the character basically invisible. Is he or she an empty canvas onto which the players can project their own identity, or did you have somebody specific in mind where you were designing the game?

Matthieu Cherubini: The original idea for the project came while I was sitting on a plane flying over Iraq, if I remember correctly. I was watching an action movie, everything on my little display was exploding and I was eating a cheese sandwich. I thought that the whole situation was kind of funny, in a pathetic way… To think that twelve kilometers below me there were people who had to actually experience situations like the one I was watching on screen for entertainment purposes. So yes, I am the protagonist. The game is autobiographical, in a sense. But the protagonist, if I may, is also most of us, that is, Westerners. Basically, the “hero” is the alter ego of the player. As you mentioned earlier, there is a deliberate lack of interactivity, so this project could have been a digital movie. But to make it a first-person view game where the viewer is participating actively was a deliberate choice to say “this person is also yourself”.

Matteo Bittanti: Another conflation between lived reality and simulation, agency and passivity concerns autonomous vehicles. Tesla for example has introduced a controversial and deeply flawed driver-less system known as Auto-Pilot, giving drivers/passengers the ability to play video games while the car is moving, which — like several “disruptive innovations” that Silicon Valley churns out at regular intervals — is not simply reckless or deranged, but criminal. In your 2013/2017 project Ethical Autonomous Vehicles, you use video game aesthetics to highlight the complexities and ethical reasoning underlying driver-less driving. Have you thought about creating a full video game based on the algorithms originally developed for Ethical Autonomous Vehicles?

Matthieu Cherubini: I never thought about developing a full video game based on such a topic. This project was part of a research I was doing on machine ethics. Its goal was to illustrate – in a simple way and for a wide audience – what type of issues machines could face once they become fully autonomous. As you mentioned, there is the tendency to treat the real world as a simulation and this is very dangerous, and on the verge of being criminal. To create the simulation, you have to generalize everything and everyone, put them into predefined concepts and simplify it to the extreme. For an autonomous vacuum cleaner, this is fine. But when we start talking about a product such as an autonomous vehicle that could potentially harm human beings, well, that’s another story…

Matteo Bittanti: One of the recurrent themes in your work is the conflation – if not friction – between lived reality and simulation. One example is Afghan War Diary (2010), a website which connects to the server of the popular first-person shooter Counter-Strike and retrieves frags (that is, player killings) in real-time. These frags, in turn, trigger a chronological search in the Wikileaks database containing over 75,000 secret US military reports on the war in Afghanistan. Based on the retrieved data, the website shows the location of the attack on a virtual Earth. The project thus connects gaming, digital maps, and online archives, creating a counter-history of the war in Afghanistan. In your practice, technology is both an instrument of surveillance and domination, but – in the hands of an artist – produces unexpected epistemological short-circuits, revealing a web of connections between the industrial-military complex, entertainment, and consumer culture. This paradox is epitomized in 36,000 feet by the juxtaposition of American Sniper and a video from the Counter-Strike eSports competitions. Marshall McLuhan famously compared artists to radars, early warning systems that can discern incoming threats brought about by technology, among other things. As an artist who primarily works with technology, what do you see at the horizon?

Matthieu Cherubini: It is a nice analogy… The artist as a radar, that is... But I personally disagree. The artist might be this sensible being who is able to feel incoming threats and then is doing an artwork about it. But then its artwork is shown in a museum or an art-related news outlet, which are looked at by equally sensible beings who are probably already aware of such issues. Therefore, in the end, we are not warning anybody about anything. We are just sharing an opinion, a way to look at a certain topic, with different means.

Matteo Bittanti: What is it like to live and work in Beijing in 2022? What kind of projects are you currently developing in China?

Matthieu Cherubini: Despite the pandemic, life has been normal here as the government has extremely strict regulations. The only difficulty is traveling as it is difficult to get out of China and even more to get back in. As for my professional activities, I’m currently working for the automotive industry where I mostly use game engines to build visualizations. For example, to create simulations of car crashes happening in China, based on real data points, in order to make accidents more understandable. That’s the job that pays the bills, so to speak. On the other hand, when I have time and motivation, I still try to work on my personal projects. By the way, I’m currently working on a simulation of 8 billion people falling into a hole over a period of one year. I’m looking for a public space that would be willing to run and display this simulation for that time period. If anybody reading this has a space and is interested, feel free to contact me.

Matteo Bittanti: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

Matthieu Cherubini: The website for 35,000 feet is down, but the game can still be downloaded for both MacOS and Windows platforms. 36,000 feet is available for download here.

36,000 FEET

Digital video (1080 x 1216), color, sound, 7’36”, 2021, Switzerland

Created by Matthieu Cherubini, 2021

Courtesy of Matthieu Cherubini, 2022