LAN party Notes

digital video (1280 x 720), sound, color, 10’ 20”, 2013, United Kingdom

Created by Mateus Domingos

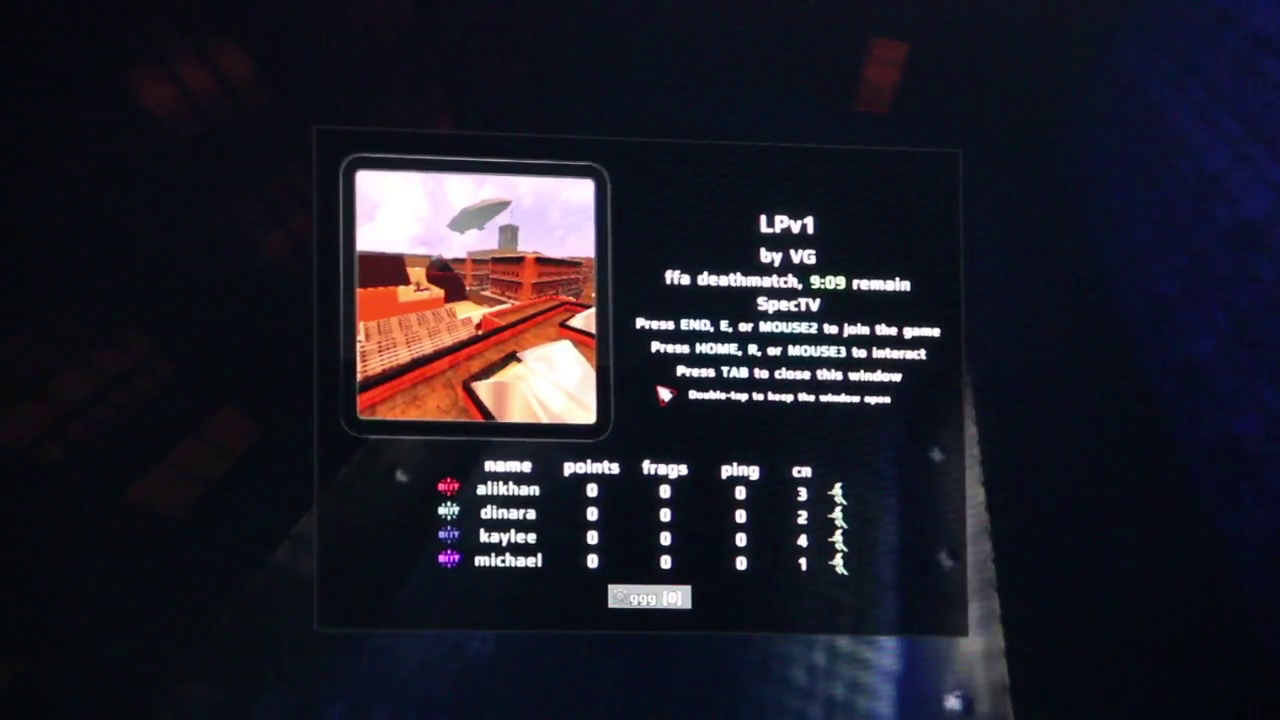

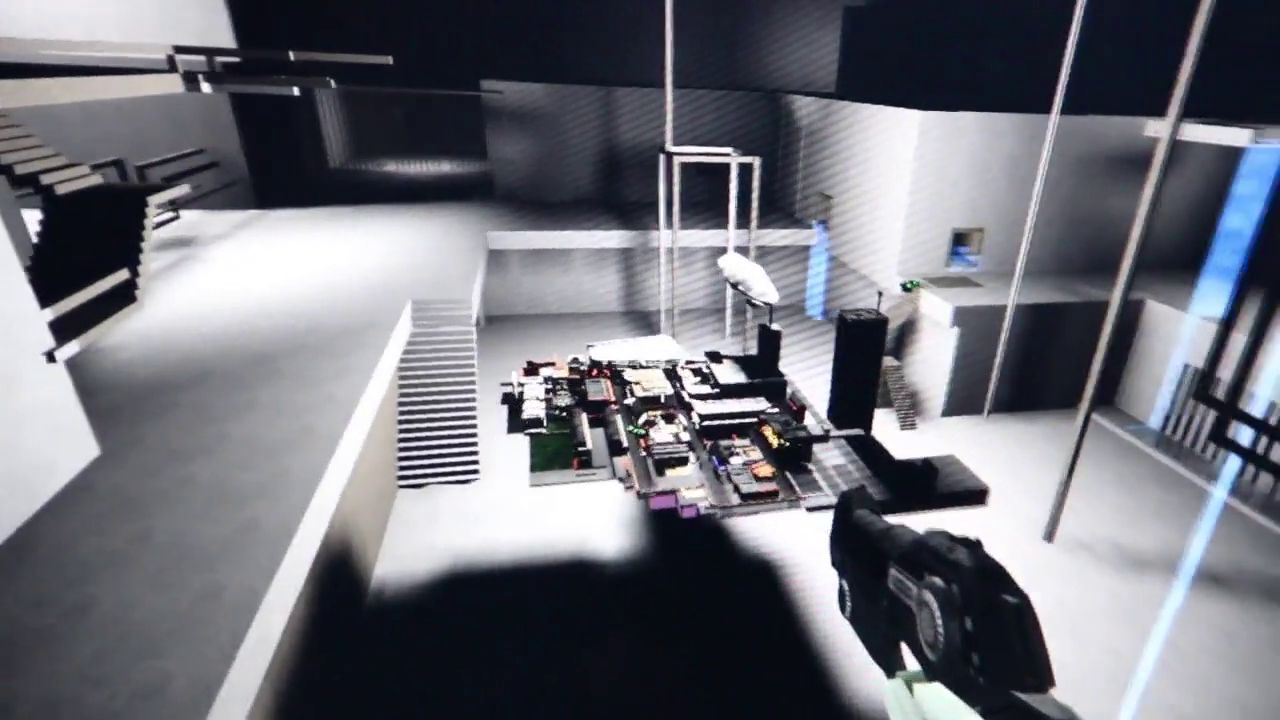

LAN Party was an installation originally created by Vanilla Galleries in collaboration with Arc-Vel and Dexter and Finbar Prior, at the Two Queens art gallery in Leicester, United Kingdom, in 2013. The work focuses on the concept of respawn which, in the context of video games, indicates the live creation of a character or item after its death or disappearance. Respawning creates an endless loop of (simulated) life and death. Vanilla Galleries’ work contextualizes such a notion in a cultural re-generation perspective, where death and rebirth are visualized through a specific interface, the first-person shooter LAN party. A specially designed custom map has been created by the collective as a place for them to exist and work over a period of time. The installation comprises a number of computers inhabiting the main gallery space at Two Queens and visitors are invited to participate in the contest of the Cultural Deathmatch in order to perpetuate the ongoing cycle of life and death within the setting of the local area network.

Also known as ghostglyph, Mateus Domingos is an artist/writer based in Leicester, United Kingdom. He was a founding member and co-director of Leicester’s artist run gallery and studio space Two Queens. He is a member of Phoenix Interact Labs and manages the publishing project Bruise. He is interested in text, narrative and new digital spaces. His work has included games, 3D printing, fictional alphabets, maps and film making. In 2012 he represented the United Kingdom in Maribor, the European Capital of Culture and World Event Young Artist. Recent exhibitions include Two Queens, Leicester, Phoenix & De Montfort University, Leicester and Modern Painters, New Decorators, Loughborough. In parallel with his artistic practice, he is a producer for the digital arts program at Phoenix, Leicester. He works on artist development opportunities and hosts a series of meetups exploring digital arts practices. He collaborates with Sweden-based Nathan Bissette under the moniker Dead Hand to produce sound, music, and broadcasts. Recently they have released a book of scores and started producing an experimental podcast. He holds a BA in Fine Art from Loughborough University. He lives and works in Leicester.

Riccardo Retez: Your artistic practice is not only eclectic but also media agnostic, in the sense that you use a variety of materials, formats, and media rather than being tied to a specific content, or formula. How do you choose which medium to use – video games, film making, 3D printing and so on – for a specific project? In other words, what comes first, a kernel of an idea or a medium through which to develop such an idea? Or are the two inseparable? How did you begin to use game engines as a site for creative and artistic production?

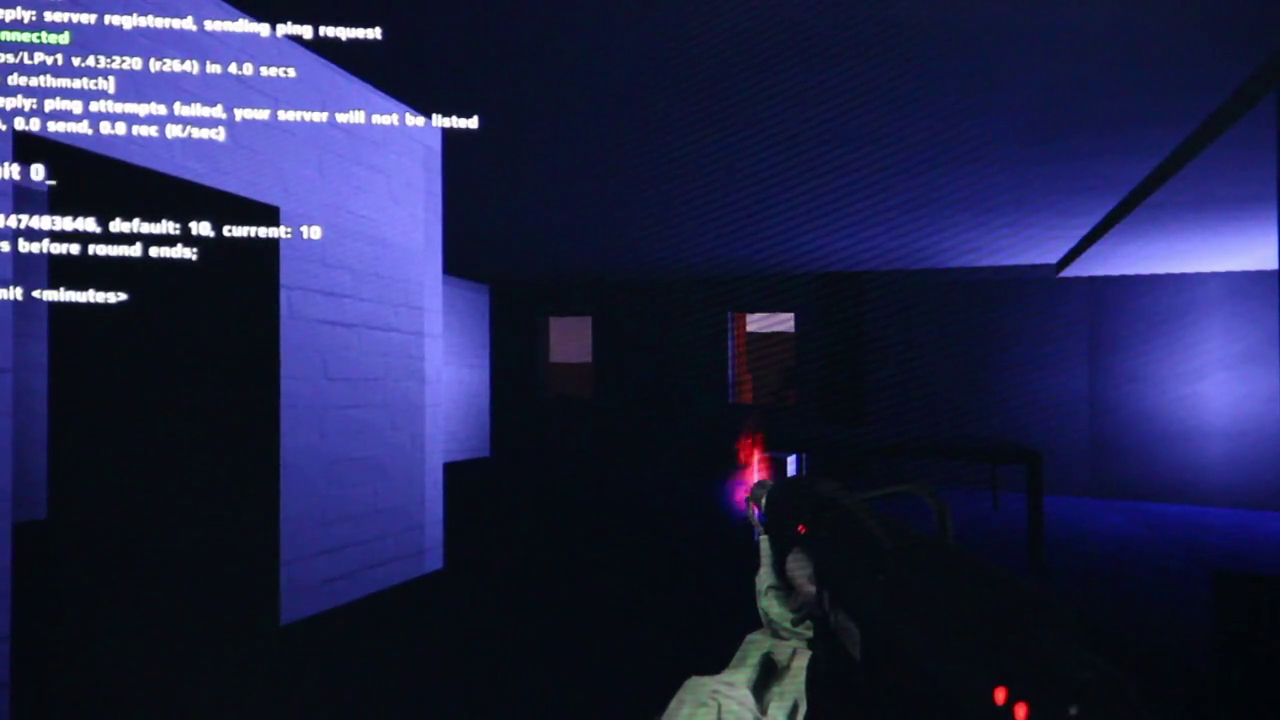

Mateus Domingos: I’m curious about fiction and experience shaped between different mediums. I think I’m often exploring similar ideas and themes with specificity to the given medium. As artists I think we need to be mindful of the platforms we utilise, so part of this constant shifting is simply about continuing to be conscious of these spaces and the ways in which they are shaping thought. LAN Party was the starting point for me using game engines as a site for creative and artistic production and particularly as a tool for discussion between artists. Prior to this, I had been experimenting with interactive fiction, and beginning to utilise game elements and thinking about play within text works. For LAN Party we were seeking a space that would allow us to collaborate in building a virtual space. Red Eclipse, an open source arena shooter built on Cube Engine offered a really interesting framework with co-op level editing. Parts of the level were built in this mode, collaboratively, essentially as a LAN party within the studio.

Riccardo Retez: The act of playing a video game requires an interaction between a body situated in a physical space and a virtual/digital body, i.e. the avatar. How does the bodily and spatial relationships dictated by the very nature of digital gaming influence your artist practice? And what is your personal relationship to this medium? How and when did you begin to experiment with gaming?

Mateus Domingos: To me, the relationship between the physical body and virtual is really important. This is where bodies connect. I have always experienced gaming as a key social activity with my peers. This has rarely been about forming virtual or distanced friendships, but developing and performing existing ones. I think this relates to the earlier point that Red Eclipse allowed a group editing mode. We sat next to each other in the room, whilst occupying avatars within a shared space. Discovering Inform was key in prompting me to explore elements of game making more closely. The use of natural language syntax makes it really accessible and intuitive. The interaction within game spaces, where the primary controller is a keyboard, typing natural language, as well as the abstracted pattern of W, A, S, D’s is this fascinating point of convergence between different ways of thinking and sensing.

Riccardo Retez: LAN Party is a meta-commentary on the notion of respawn, itself based on trial and error, gradual improvement, and “learning by doing”. This pedagogical formula exemplifies a typical Western ideology and it is grounded in a specific teleological form of learning. What role do video games play in reinforcing existing cultural models?

Mateus Domingos: Wow, yes, it’s the specific respawn of the deathmatch too… if we were making LAN Party today perhaps we would have built it around a Battle Royale mode which, seems to shape a different kind of respawn, a YOLO [You Only Live Once, Ed.] attitude. It feels like video games are hugely significant in reinforcing cultural models as well as shaping and facilitating new cultural models. Games are a place where imaginary and real things happen. The way we play games folds back into other parts of our lives, gamification of work tasks, loot boxes, micro transactions and even the spaces like Twitch and Discord that facilitate a specific kind of spectatorship now direct that mode of spectatorship towards other things too.

Riccardo Retez: As a site-specific performance, LAN Party recreates within a digital context the spaces and places of lived reality, i.e. the streets of Leicester. What is gained and what is lost in this translation? And why do you think that this kind of performance is relatively rare? Aside from the usual suspects, e.g. Eddo Stern’s early works, Franz Lantz’s PacManhattan or Blast Theory’s entire oeuvre, there are relatively few examples of mixed reality, game-based experiences…

Mateus Domingos: LAN Party gave us a space to explore the area. Many of the building interiors were invented based on rumours we had heard, the stories people told about the place. Other places were pure fantasy that seemed to emerge from the site of the game itself, such as the underground labyrinth. Playing the LAN Party within the location being presented created an odd sense of unease and familiarity. I think we could only have made the LAN Party we made through our lived experience of the place, and it was that lived experience that we wanted to explore.

With the last year in particular there have been a bunch of projects created that perhaps make this kind of experience easier and more familiar to people. For instance, LIKELIKE, gather.town, Mozilla Hubs. Of course Minecraft and Roblox also continue to be hugely important. The barrier to entering those spaces has reduced, and so perhaps as we return to physical spaces we’ll see more use of mixed reality spaces exploring games and play.

Riccardo Retez: In LAN Party, the mix of real and virtual is underlined not only by the visual component of the installation, but also by sound. The raw, live audio produces a cacophony and, at the same time, provides some kind of contextualization. Can you elaborate on LAN Party’s unique sound design? Arc-Vel and Dexter and Finbar Prior’s live soundtrack reminded me of the orchestras playing music in movie theaters, before the introduction of the so-called “talkies” in the late 1920s…

Mateus Domingos: It was incredible to experience the game with live musicians performing. The acoustics in the gallery created this really overwhelming and chaotic space. We collaborated with several local artists and musicians for the LAN Party exhibition. I believe part of Dexter and Finbar Prior’s performance was built around the startup tone of the PlayStation. I think we were interested in these elements of game culture that had bled-through into our culture generally. The laptops were all played from within a plywood fort, covered in netting and camo spray paint, which looked like a paintball centre recreation of a sci-fi shooter.

It’s interesting to think about that moment when parts of the experience are synthesised or changed, live sound becoming part of the film, and what happens if those elements move apart again. With VR installations there is obviously increased digital sensation, but we also see more use of physical staging/seating and touch. In LAN Party we also partnered with a local energy drinks company, so everyone, bizarrely, was experiencing the taste of a LAN Party as well.

Riccardo Retez: LAN Party casts the viewer not as a passive subject, but as an active participant, subjected to a recursive loop of life and death dictated by the respawn, hereby defined as “the live creation of a character or item” and “the recreation of an entity after its death or destruction”. There’s a long tradition in the art context related to delegating some authorial agency to the audience, so that the viewer becomes the co-creator of the artwork. In this sense, games and contemporary art share many features. But what are the limitations or pitfalls of viewer’s engagement? Does participation lead to hellish outcomes, as Claire Bishop has famously argued?

Mateus Domingos: LAN Party existed as a space for visitors to enter. It was almost certainly a hostile space, in which the loop of life and death was enforced by bots that roamed the level. Discovery and participation within that space had to be earned. Knowledge could be shared between players who were shoulder-to-shoulder in the space.

A limitation perhaps, is that the staging of LAN Party is no longer accessible. We have odd bits of documentation and LAN Party Notes. It should be possible to still play the level in the current version of Red Eclipse, but the landscape has changed. The karaoke bars have closed. New blocks of flats have been built. It is more of a dream now. At the time, LAN Party was presented within the context of works by other artists and musicians, as mentioned, so the engagement for a viewer was related to this wider exhibition experience, and the conversations that happened within that space.

Riccardo Retez: The participatory and experiential model of LAN Party is reminiscent of the paradigmatic model of the arcade, which relied on a situated experience in which players used to challenge each other at their favorite games. These days, eSports tournaments have all but replaced that model, adding an obsession for live broadcasting that was largely absent from the old arcades. How did the history of video game competitive play influence the design of LAN Party?

Mateus Domingos: We really wanted to play with that sense of the arcade experience. For most of us working on the project, that experience was specifically a Midlands one, likely restricted to a small cluster of machines at the bowling alley. The localised nature of arcade competitiveness is really important, I think. In the exhibition we also screened a documentary called Lord of the Dance Machine, which follows K-Dogg, a Dance Dance Revolution player, from Leicester as he tries to compete internationally. One of the challenges he faces is the demolition of the bowling alley that housed the machines he would practice on.

One removal we made in LAN Party is that element of competition, or the resolution of it. We didn’t organise games, and there were no coherent high scores. I think we were more interested to see what kind of play emerged within those ongoing constraints. Around the same time we also began playing Rust. We would be together in the room, much like when we were working on LAN Party but instead of building something locally, trying to survive on someone else’s server.

Riccardo Retez: Is there anything you’d like to add about your project and/or practice?

Mateus Domingos: Thank you for the opportunity to revisit this work. The level was built collaboratively with the artist collective Vanilla Galleries. This was exhibited in the LAN Party exhibition at Two Queens in 2013 and documented here. LAN Party Notes was created shortly after the exhibition using in-game recordings mixed with audio recorded whilst walking around the location portrayed in the level, along with sounds of other players and the live soundtrack performed by Dexter Prior. I post about my practice here and can be found on Twitter @gh0stglyph.

LAN party Notes

digital video (1280 x 720), sound, color, 10’ 20”, 2013, United Kingdom

Created by Mateus Domingos with Vanilla Galleries, 2013

Courtesy of Mateus Domingos, 2021