HOME/NOME

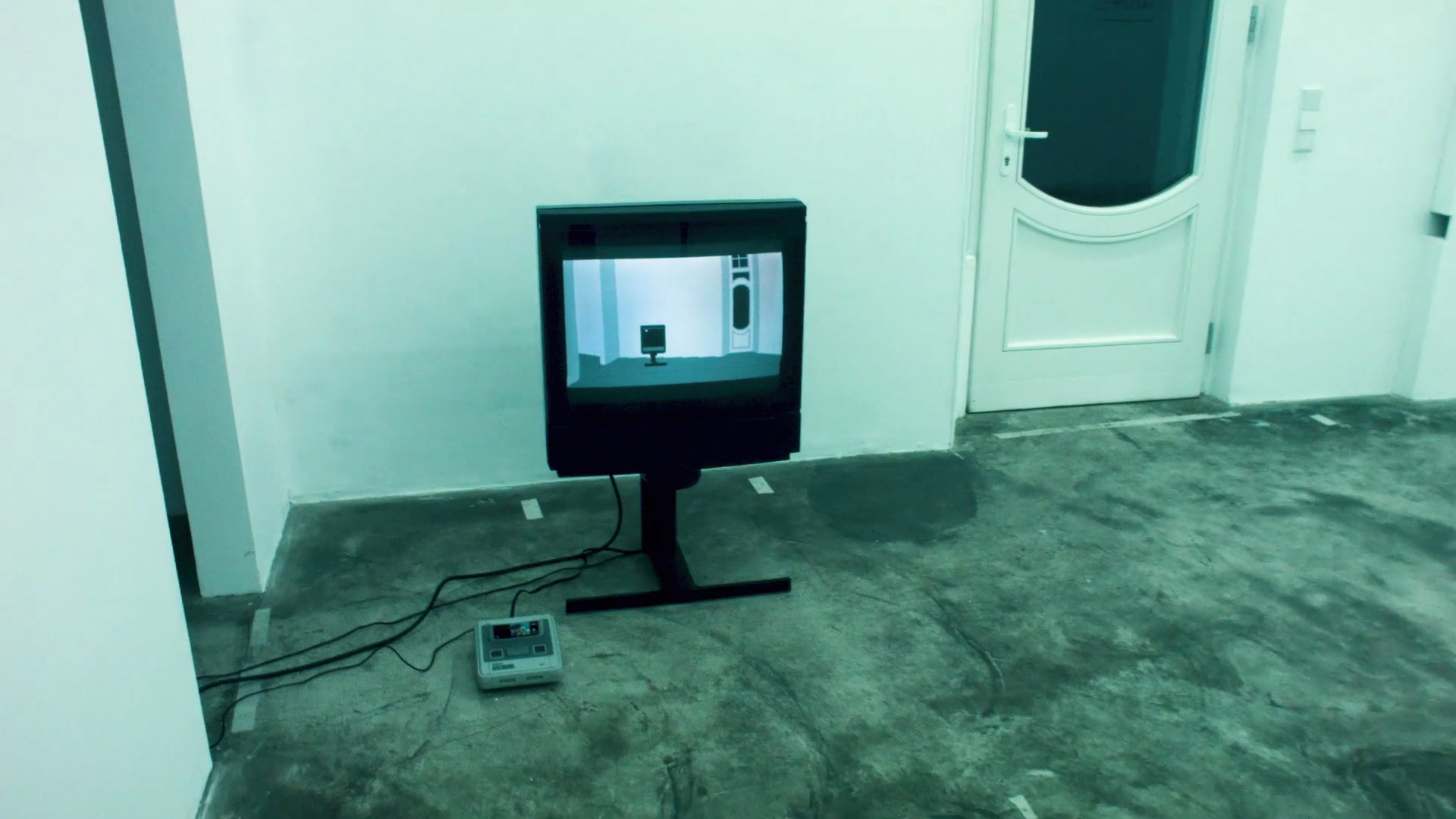

video installation, SNES game consoles, animation, video, Hi8, miniDV, Bang & Olufsen 90s TV sets, hereby presented as digital video, color, sound, 4’ 16”, 2021-2022, Germany

Created by Lars Preisser

NOME/HOME is an immersive video installation exploring the relationship between memory, interior design, and video games. Specifically, NOME/HOME recreates Preisser’s former Berlin apartment through the pixelated rendering of Mario Paint, breathing renewed life into the spaces he once inhabited. Participants traverse disorienting rooms as Preisser’s own voice echoes hauntingly around them. This audible tableau juxtaposed with the visual fragmentation of the gaming software creates a palpable sense of nostalgia and loss. Visitors are transported into uncanny reimaginings of real spaces that over time have been distorted by the urban forces of gentrification. By reviving the past through both analog and digital artifacts, Preisser contemplates the ephemerality of memory and the erasure of history in the built environment. NOME/HOME provides an entry point to meditate on the entwined nature of place, recollection, and selfhood within the ever-changing terrain of the city.

Lars Preisser is a multidisciplinary German artist whose work spans various media including weaving, drawing, and moving images. Born in 1984 in Lindau, Preisser holds degrees in textile art and media art from Otago Polytechnic and HGB Leipzig. His research-intensive projects result in intricate formations that address issues like gentrification, technology, climate change, and post-colonialism through a personal lens. Preisser’s family heritage and background in industrial machinery inform his practice. The artist has exhibited internationally at venues like Bauhaus Dessau, nGbK Berlin, and the contemporary textile art biennial Contextile among others. Preisser spent formative years in New Zealand before returning to Berlin where he currently lives and maintains an active studio practice.

Matteo Bittanti: The relationship between memory, spaces and the very idea of domesticity is central to NOME/HOME. Could you speak more about how you investigate this connection in your work?

Lars Preisser: For the project, the media ecology becomes really important, I specifically use devices from the 1990s that I played with as a child at home in the old apartment in Berlin. I wanted to have a direct link to the past on a material, technological level. By setting up these devices in the gallery and making a video of this exhibition setup, I playfully repeat what I did in the same place as a child. Through this artistic intervention, the rooms should become my home again for a moment.

Matteo Bittanti: I love this idea of re-enactment. But why did you specifically incorporate elements of video games into an installation exploring both memory and interior space? How do you see the interactivity and immersion of digital games adding to the viewer experience? I see that you also mentioned electronic games in your previous project Time of the Wastelands I, and specifically the Tacheles market, where you used to swap second hand video games, which makes me think that like mine, your youth was marked by different generations of consoles, from the SNES to the PlayStation. Additionally, you incorporate game cables in your work Cable Tapestries. Am I correct to suggest that game technology left a mark in both your topological memory of Berlin and the interior design of your home, that is, outdoors and indoors?

Lars Preisser: That’s true; games have always fascinated me and they are a special medium to me. There’s not only the immersion but also the interactive and creative components. With each new console generation, there were also these very strong visual and spatial changes that fascinated me, like the move from 8-bit to 16-bit and then the stark change to 3D – it all seemed to happen very quickly in the 1990s and this progress was a big part of the appeal for me. Each of these console generations also conveyed their own unique moods or stylistic traits almost like with art movements. If 16-bit games were like impressionist paintings or ancient mosaics, then the original PlayStation or Nintendo 64 games were like cubism and by now you’ve almost reached ultra-realism.

Being able to trade consoles and games at the flea markets in Berlin was the perfect opportunity for me to play a lot of different games without having that much money. The games and the places where I was able to buy or trade them and where I played them are linked in my memory. Later, as an artist, it made a lot of sense to me to use video games or mention them for example when I filmed the disappearing wasteland where my favourite flea market used to be. I don’t even know what exact years it was when I was there but I think about that time in terms of specific generations of game consoles.

After leaving Berlin and moving to a small city in Aotearoa/New Zealand, I studied textile art and maybe it was my relation to gaming devices and cables that formed this idea of including them in a fabric. At first I was actually more interested in the conceptual possibilities of running sound through a fabric. Later I became more fascinated by the range of cables from different devices and different times and started to use them for pure aesthetic reasons or to comment on a society that becomes more and more digital.

Matteo Bittanti: In many ways, NOME/HOME explores the theme of the uncanny. How does this theme relate to themes of memory and nostalgia? Is this a way for you to question the “authenticity” of memories, or are you more interested in the fiction of “home”, in the fantasy of “domesticity”?

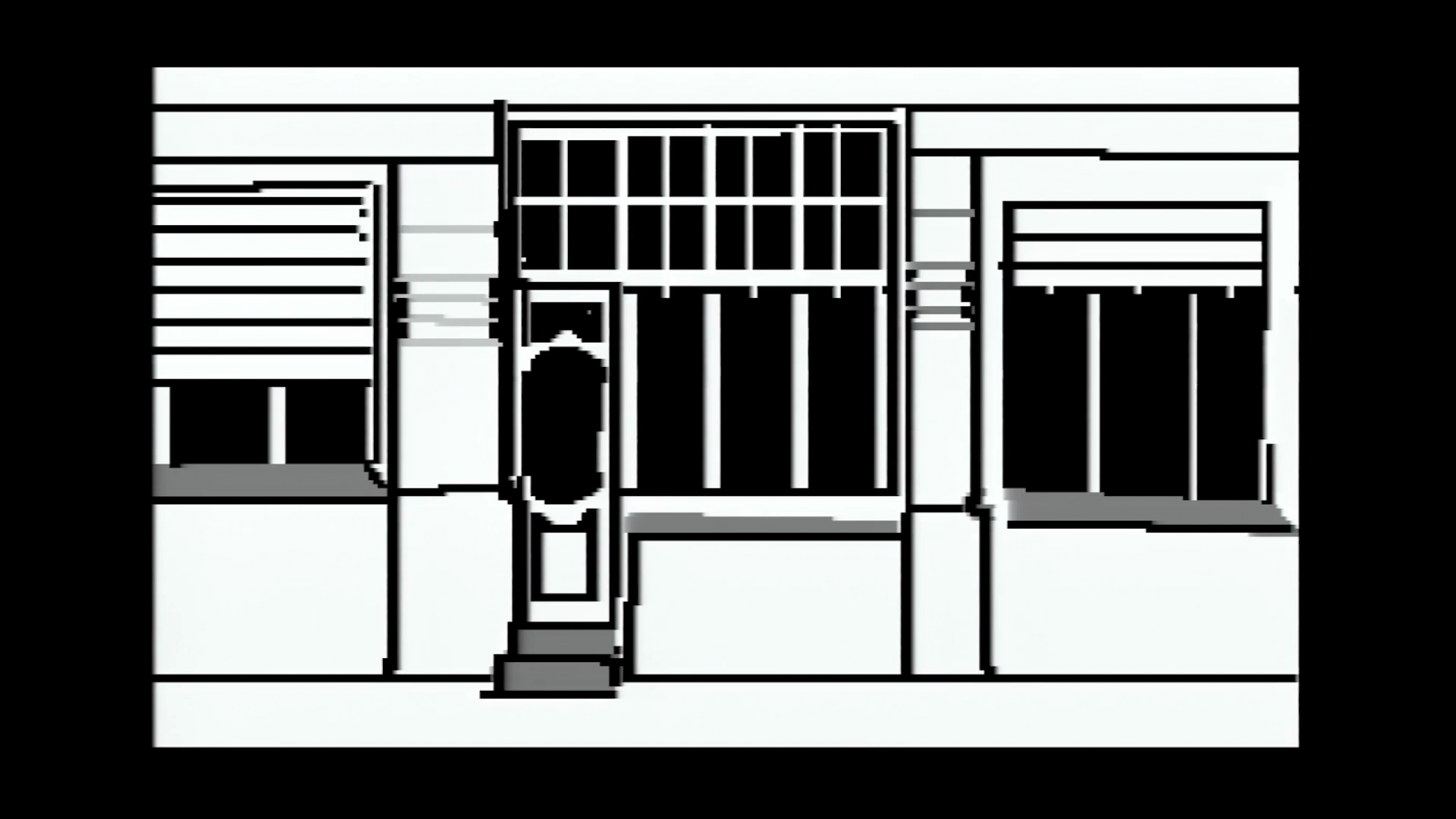

Lars Preisser: I was really motivated by the idea to revisit my former home through the means of art. To use the possibility of returning into a building that I once lived in and doing something there that I already did as a child was a logical consequence. Art and the SNES game Mario Paint gave me the opportunity to return into this totally changed environment and create a link between the past and the present. The whole idea became almost a bit like a video game mission in itself. I had thought up several tactics for approaching the gallery not only to realize this fantasy but also to somehow incorporate the process of contacting the gallery. I thought about sending them some of the old home videos like in Michael Haneke’s Caché for example.

Matteo Bittanti: Genius.

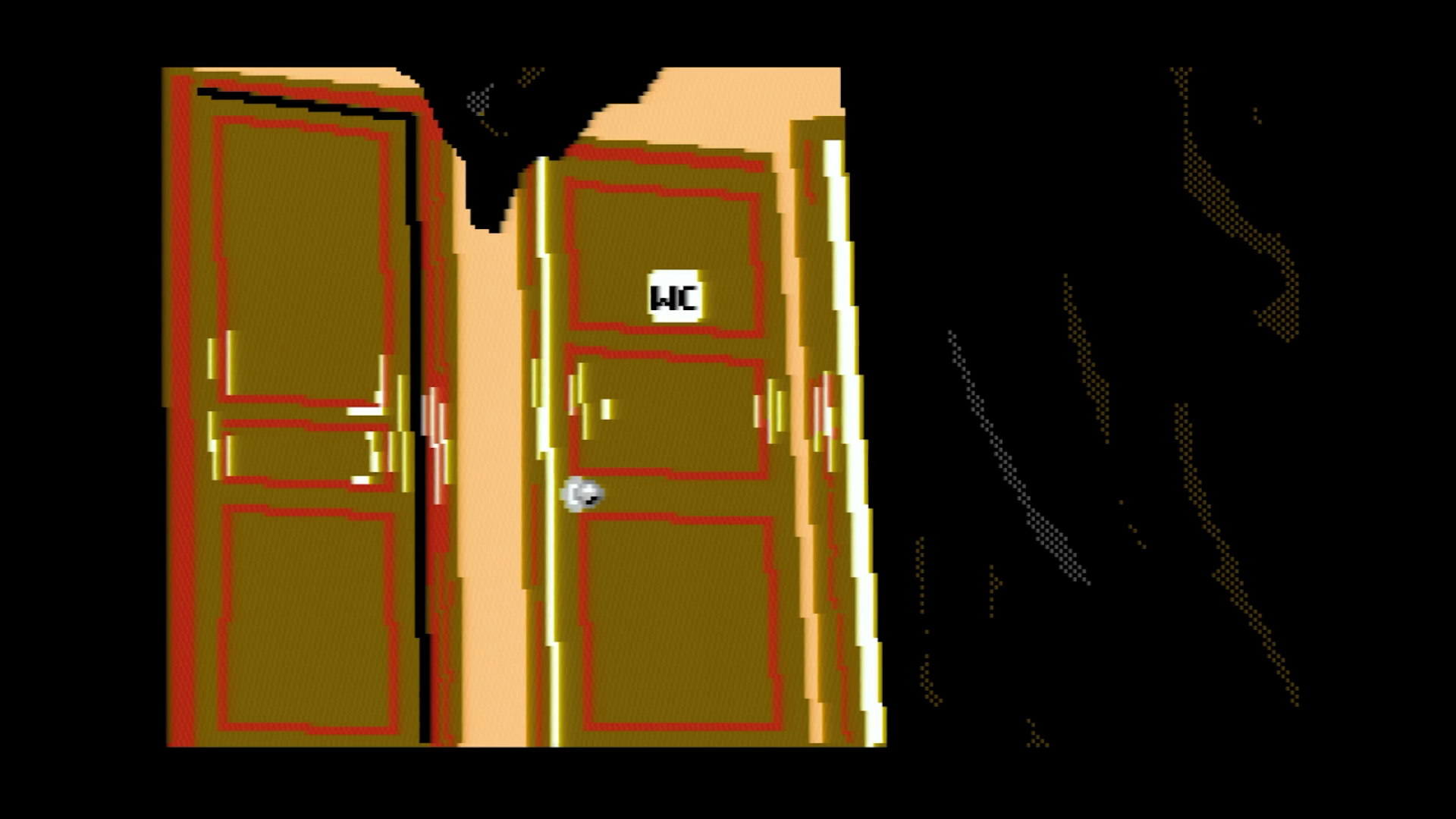

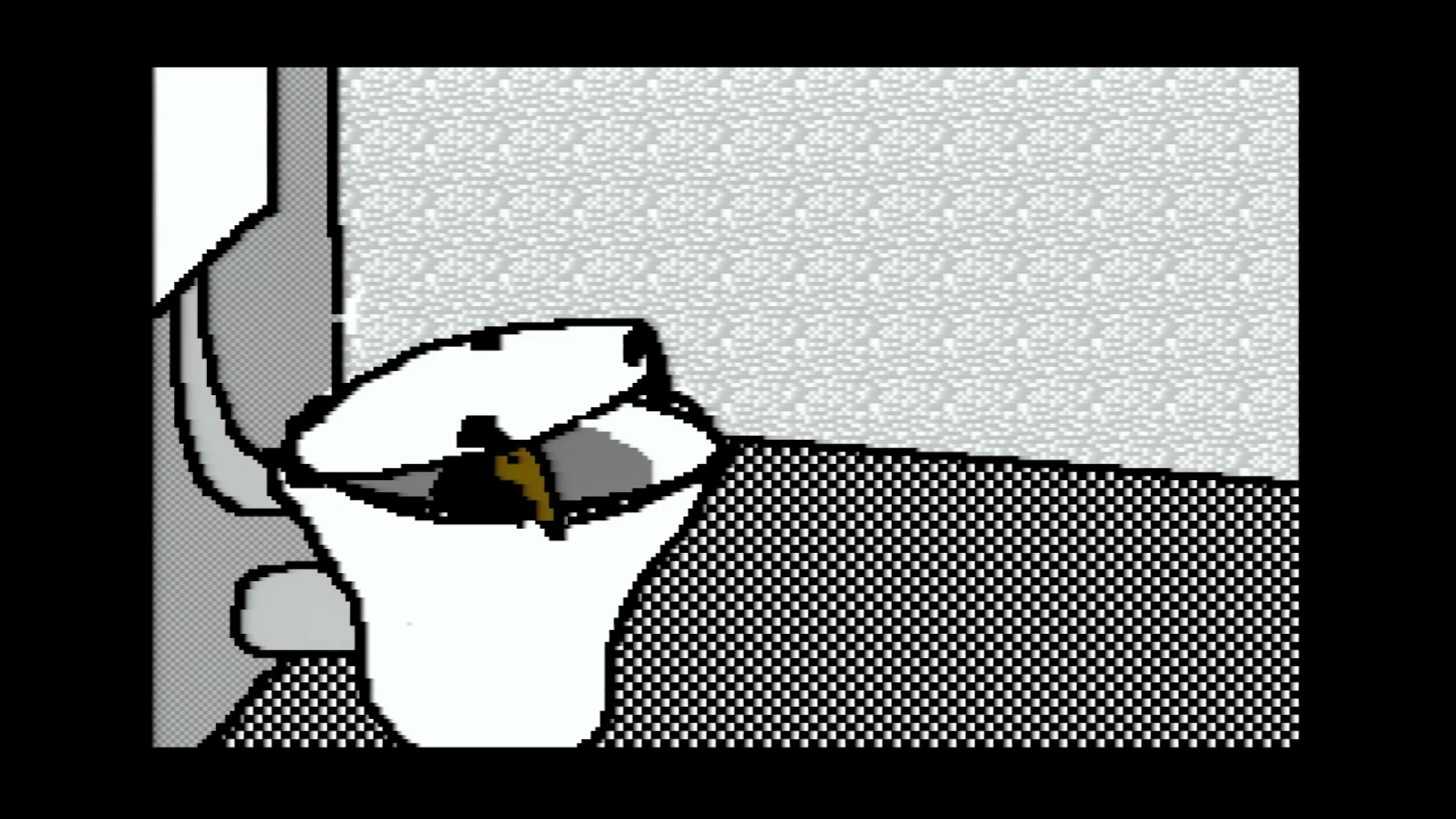

Lars Preisser: There was some uncanniness in it from the start, even to me. It’s not how art exhibitions are happening usually and some of the animated memories are particularly uncanny. For example when we had rats coming in through the toilet so we had to seal the lid with tape during the night. My father was also running a small bar in the front room and in one of my animations I show the hand of a drunken guest opening the toilet door in our shared hallway that was only separated by some black fabric. In my exhibition setup there are also these TVs that turn their screen towards you when you turn them on, things like that make it more alive and real I find.

Matteo Bittanti: Gosh, rats coming out of the toilet is my idea of hell. I guess I have never recovered from Bret Easton Ellis’ American Psycho. On a lighter note, your process of “animating memories” through a Mario Paint machinima is fascinating. By using Mario Paint in such an unexpected and original way, you are exploring themes of memory, loss, and the passage of time, even mapping out the original apartment. As the etymology reveals, “to animate” traces back to the Latin animare, meaning to impart life or soul. In recreating personal spaces with this retro video game software, you are essentially breathing new life into your memories and past. I’m curious to learn more about your artistic process. What drew you to a tool like Mario Paint for this project besides the fact that you first encountered it in 1995? What techniques did you use to accurately capture and recreate real environments within the limitations of the software? Were there particular challenges you faced in translating video footage into Mario Paint compositions that evoke a sense of dimension and space?

Lars Preisser: I like mediums with limitations, the strict limit of possibilities is a motivator to become creative with a medium and really test out its boundaries. Interestingly this is also part of Nintendo’s own product philosophy of lateral thinking with withered technologies. To use such a medium in art is also not that common and therefore I can avoid preconceptions of my audience and also I can afford to make mistakes as there is no real benchmark for this kind of art.

I basically just used my drawing skills to recreate these old rooms partly from memory and partly also from stills of old home videos. I did not aim for a photorealistic look but used the most basic drawing tools of Mario Paint to draw, some basic shapes and three sizes of brushstrokes. In the process I realized that there are actually more complex possibilities within the game. There is a thing called the stamp tool basically allows you to create and save a number of your own brushes on an area of 15 x 15 pixels so you can create quite detailed little stamps or even very fine brushes that only fill one pixel at a time, as a child I never really understood this function very well. But you could actually take a real photo and bring it down to the game’s resolution and color range and then recreate that photo pixel by pixel. But that would look a lot more flat, less like in a game and more like a mosaic or a very bad photo. Another problem is the SNES mouse which came with the game and which is pretty hard to control so it is quite a rough process and it takes some time. On top of all that you can save only one final painting on the cartridge and since this save game relies on an internal battery it happened to me that the next time I would start the game, the image was gone because these cartridges are just really unreliable. Because of that I started to screen capture the whole drawing process and the final results so I would have a backup on the pc at least.

Matteo Bittanti: Apropos Mario Paint, I would like to ask you about another project of yours, Animated Urban Spaces. Can you provide further information about this video work? What is its relation to HOME/NOME?

Lars Preisser: That is a little spin off work that I made for an exhibition curated by Berlin’s project space network. Local project spaces are struggling partly because they do not get nearly as much support as the big institutions. In this work I show more of the working processes of Mario Paint by screen capturing the actual drawing process. I drew several cultural institutions for example, the Palace of the Republic (Palast der Republik) as well as the much criticized new Berliner Schloß (Berlin Palace) which was rebuilt in its place in a fit of historical revisionism. I also made a composite of both buildings in Mario Paint, which I think could have been a much more exciting architectural symbol for the unification.

The Palace of the Republic originally hosted the parliament of East Germany but in the 1990s it was an empty space for a short period of time and people actually used it for exhibitions and it became a palace for the people before it was demolished.

Matteo Bittanti: The fractured layout of the space that comprises the installation NOME/HOME seems intentionally disorienting. What were you hoping to evoke by breaking up the interior architecture and space in this way? Providing glimpses of History, that is, the evolution of a city, Berlin, or rather, a story, that is, a moment in time in your biography, rather than a linear and cohesive narrative? What do you hope viewers took away from the experience of navigating the virtual interior landscape you’ve created in the gallery space? It seems to be that you were using concrete spaces as if they were the level or settings of a video game. What feeling or ideas would you like them to leave with?

Lars Preisser: I decided to set up one SNES and one TV in each of the former rooms but since the layout of the place changed over time there are now two different layouts that are superimposed. You can sometimes spot similarities that evoke a sense that there is actually a connection of what goes on inside the TV and the specific placement of it. I hope that this somehow becomes clear even just by watching the video a couple of times and slowly understanding what is going on. I liked that idea of moving through the space with my camera and filming the two realities of the rooms at the same time. Even in its original state the apartment has been a bit of a labyrinth and when I set up my exhibition I rediscovered the new layout of the place for the first time so me and the camera are more than a neutral observer.

Matteo Bittanti: How do you see the work speaking to issues of gentrification and the erasure of history in urban environments? I’m specifically referring to the episode of the baby buggy on fire in the hallway. You wrote: “My parents came to Berlin (to be artists) in the ‘80s and rents were already on the rise and not everyone was happy about that.” It’s all fun and games until the entire building burns down I guess.

Lars Preisser: The hallway was actually the place that still looked the most unchanged and I never understood the reasons for the burning buggy when I was a child. I always thought it was just some random thing. It was only as an adult when I learned that this was actually a thing in Berlin and that it had to do with gentrification. Luckily the hallway is all tiles, still it is a stupid and extreme measure but it also drastically shows that gentrification is a real issue that needs to be attended to.

Matteo Bittanti: Remarkably, the gallery space that replaced your childhood apartment is called NOME, which has many connotations. It could be a reference to the Italian word “nome” meaning “name”, relating to identity and one’s relationship to space. It could also be drawing from the etymology of “know/gnomy”, having knowledge of a place that feels like home. I wonder if you could elaborate on the title of your work.

Lars Preisser: Yes, that was another really surreal coincidence. The director of the gallery is originally from Italy so the connotations you named are probably fitting. My little wordplay or rhyme HOME/NOME also translates quite well into the limited animation possibilities of Mario Paint in which I only had to animate the N of NOME to become an H for HOME.

Matteo Bittanti: Ha! Occam’s razor strikes back. As a multidisciplinary artist, how does this installation relate to or depart from your work with other mediums like weaving, drawing, and film? Do you see connections between NOME/HOME and your wider artistic practice? I’m especially interested in the relationship between technology and urban/domestic spaces which recurs in several of your projects.

Lars Preisser: In the past I often had the feeling that my various practices were too different and that I would have to make a decision at some point in order to be successful as an artist, but the more deeply I looked into individual practices, the more overlaps and relationships I discovered. These overlaps or similarities are interesting because they raise exciting questions for me. The limited possibilities of weaving patterns show similarities to pixel graphics of simple video games, I remember many years ago I hand wove a pixelated 8-bit Super Mario figure because the pixel count of this figure exactly matched the possibilities for a pattern on my loom. Weaving itself is somehow a digital medium whose functionality is based on a binary logic. Groups of threads are either raised or lowered by pedals, roughly corresponding to the ones and zeros in binary code. Through the opening of the different raised and lowered threads another thread is woven. Depending on whether threads then cover this woven thread at the end or run under it, a pattern results. For me, weaving is probably the first digital art form. Among other things, it was also this circumstance that moved me to weave materials such as cables of electronic devices and partly also to let information such as sound or video signals flow through these fabrics.

I find such connections between ancient craft and modern technology extremely exciting. My work almost always deals with the interplay of past and present and I often use specific tools from different times like current game consoles or 16mm analog cameras from the 1940s or hand weaving to condense ideas methodically and structurally. For the project that deals with Berlin’s wastelands, for example, I use the 16mm camera to archive the remaining wastelands on film. Many of these empty spaces date back to the war and they really shaped post-war Berlin so my camera is also from this time. In the meantime, almost all of the wastelands have been built on now and the city is becoming more and more claustrophobic. During the Covid-19 pandemic, I started to travel over Berlin in Microsoft Flight Simulator on the latest Xbox console. The data on which this virtual Berlin is based is from about 2008 and so there are still some wastelands that I could not archive in the real version of Berlin so I used the virtual drone camera in the simulator to take pictures and videos of these virtual wastelands. If you come close these virtual wastelands appear still unreal and flawed despite the advanced graphics. Currently I am experimenting with analog media like 16 and 35mm film to make the virtual wastelands seem more real and to somehow still capture the beauty of the old emptiness in my plea for the wasteland.

Matteo Bittanti: That sounds like a fascinating project. And it is part of an ongoing meditation on space, memory, and media. Time of the Last Wastelands is a complex, multi-layered multimedia project exploring vanishing post-industrial landscapes through such media as experimental filmmaking and billboards. So far, you have produced two major installments, I and II, both capturing the liminal zones of Berlin. Could you speak about your process for digitally altering the film footage using glitch and distortion effects? How do these techniques reinforce the thematic content?

Lars Preisser: The original footage that I shot on 16mm is quite messy because I basically walked around scanning the areas sporadically using a low frame rate like 12 images per second while I walked relatively fast to save film and also because I was somehow in a hurry because these wastelands were disappearing day by day. But then I wanted to get more out of the material later and had it scanned. I slowed down the film so that each individual film frame is visible for 1 second. This gives the viewer more time to see details of each frame, at the same time I removed a lot of frames so that camera movements like a pan become even more obvious and the film moves forward noticeably. To make the change in between frames visually and structurally fitting I animated each frame so that it moves from the top of the screen to the bottom every second, mimicking the movement of film in the camera or as if running on an analog projector referencing the old technology. Undetermined in between still and moving images the work appears like a countdown for the disappearing wastelands. By stopping each frame briefly I try to hold time and briefly capture the temporary state of the fleeting void.

HOME/NOME

video installation, SNES game consoles, animation, video, Hi8, miniDV, Bang & Olufsen 90s TV sets, hereby presented as a digital video, color, sound, 4’ 16”, 2021-2022, Germany

Created by Lars Preisser, 2021-2022

Courtesy of Lars Preisser, 2023

Made with Mario Paint (Nintendo, 1992)