WOLFPATH.EXE

digital video (1920 x 1080), color, sound, 4’ 04”, 2017, Turkey

Created by Kadir Kayserilioğlu

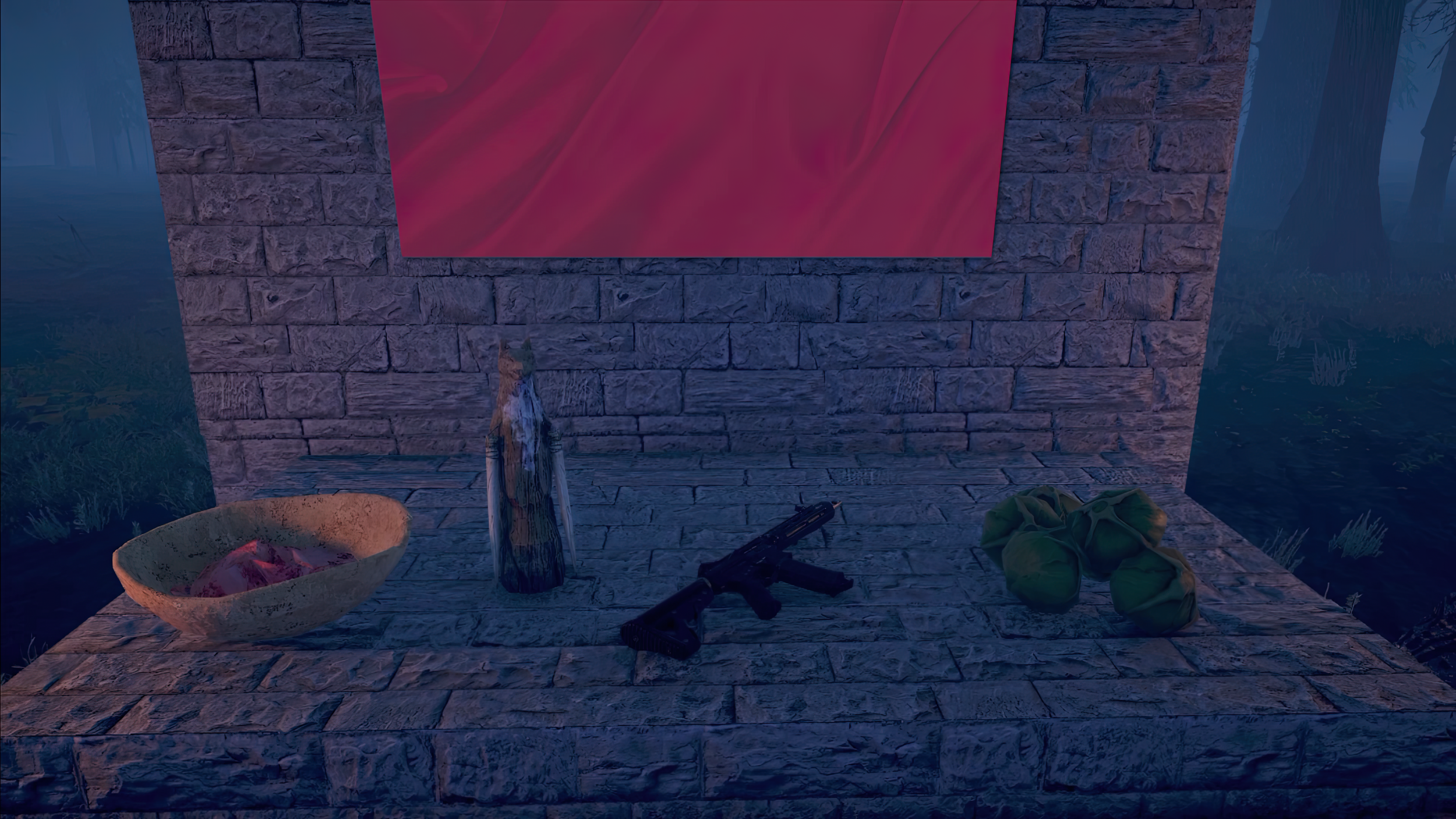

Updating a traditional origin myth through video game aesthetics, Wolfpath.exe is a meta-commentary on contemporary Turkey from the perspective of a young artist engaging with technology, popular culture, politics, and folklore. By directly confronting the technical and ideological constraints of Far Cry 5, a popular video game developed by French giant Ubisoft and a “paradigmatic example of the politics of videogames in the face of an ongoing ‘anti-progressive/anti-feminist backlash’ in the United States” — as Sören Schoppmeier convincingly argues in his essay “Playing to Make America Great Again: Far Cry 5 and the Politics of Videogames in the Age of Trumpism” — Wolfpath.exe forces the viewer to rethink the impact of game culture on the collective imaginary.

Born in 1987 in Istanbul, Kadir Kayserilioğlu received a B.A. in Graphic Design and an M.A. in Fine Arts from Yeditepe. He is currently pursuing a Doctorate program at Marmara University, while making and exhibiting art in Turkey and elsewhere. His practice is grounded in the idea that play operates across a wide range of forms including video games and collaborative, performance-based video and imagery. His works often rely on a combination of instructions and protocols on one hand, and collective improvisational processes and chance operations on the other. This often results in works that challenge conventional notions of authorship and authority, imbued with a dark humoristic style, showing irreverence towards traditional hierarchies between forms of high and popular culture, assembling high production value with home made and DIY esthetics. His areas of investigation include the nature of social reality, gender, identity politics, populist tactics, posthumanism and micro-stories. He often engages in strategies of the absurd, repurposing mythological narratives as well as science fiction and horror tropes towards a critical take on contemporary political dynamics.

Matteo Bittanti: What does it mean to be an artist in Turkey, today? What kind of challenges do you face?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: As you may know, Turkey has been struggling for a long time. It’s a fact that the current government is not kind to the groups of people who do not support their views and politics. Such behavior has had terrible effects on several groups. It has affected people belonging to different classes, ethnicities, and genders. Artists are only one of these social groups finding themselves under attack. The intense pressure was exacerbated by the ongoing pandemic and the economic recession. In a country where political pressure is so high, it is frankly absurd to talk about freedom of expression. The risk of self-censorship is very real. Nonetheless — or perhaps because of all these constraints and challenges — artists have been able to create effective coping strategies. For instance, we saw the emergence of independent collectives, underground organizations, and bottom up activities that allowed for a flourishing of activities, including exhibition and gestures of solidarity. This form of organizing made life tolerable for many young artists. For instance, I began by exhibiting my work in small local galleries and bars. This DIY approach ultimately paid off.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe your relationship to video games and video game culture, two sites where politics are symbolically acted out?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: This is not an easy question for me to answer. I must clarify that I do not consider myself a “gamer”. I never was. Being a gamer seems to be like a full time profession, one requiring a considerable investment of time, money, and resources. Besides, I have little interest in big commercial productions, the so-called triple A games and the likes. I do not expect much from gaming as a medium. There’s very little creativity. I don’t really see a future in this kind of production. I am much more interested in indie games and art games. I would not consider the latter “video games”. The term video game is inadequate to describe these systems that allow for deep experiences and forms of engagement that go beyond shooting everything that moves on the screen. To me, researching art games and experimental art games was like diving into an ocean. I realized that this context is much more lively, stimulating, and engaging than the mainstream video game scene. It is also more democratic, insofar it has become easier for aspiring designers to produce high quality interactive experiences using accessible tools that are often freely available. When a market previously dominated by capitalist imperatives and a mass manufacturing logic is reinvented by the creative output of small, independent artists, it can really become something powerful.

Matteo Bittanti: How would you define “play” in relation to your artistic practice?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: Play is the underlying force of my artistic practice. It’s like an urge, an urge to play. Playing is an undetermined activity that has no fixed beginning and end. It’s a process that can produce unexpected outcomes. I’m very inspired by how avant-garde movements of the Nineteenth century incorporate play in their art. From DaDa’s approach to chance and randomness, to automatic writing and collaborative “games” like exquisite corpse, not to mention the provocations of the Situationist International détournements, play is pervasive. Serious play becomes an act of deconstruction. You can use play to dismantle powerful institutions. Through role play, you can better understand the notion of identity: yours and others’. Play can be a strategy of resistance. But also a tool to discover new things. My artistic practice is driven by a playful attitude that leads me to interfere with readymade objects, found footage or existing artifacts and use them against their original or intended purposes. It’s a process of appropriation and reconfiguration that may culminate with a machinima or video or a performance or a collaborative endeavor. All these activities develop organically. I find it all very playful.

Matteo Bittanti: In your oeuvre, video games aesthetics are a recurrent theme. For instance, to create Nomads, you appropriate some video footage from Age of Empires II, and to create My Haunted House you used The Sims. As an artist, what are the advantages and limitations of working with video games?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: In my case, the choice of a medium is more related to personal closeness than pragmatic reasons. To be more specific, I approach video games as a huge repository of images. What I am trying to say is that each video game is a visual archive that can be endlessly repurposed. Some video games actively encourage users to do so: they feature editors to turn your experience into a photograph or a film. It’s really up to the artist’s interest to pursue such n approach. One can significantly shape and modify the virtual world to make it closer to her or his artistic vision. In my case, I used the variety of assets and design options offered by Far Cry 5’s map editor (Far Cry Arcade) and Valve’s Source Filmmaker to create my video. These tools are really versatile. I am also interested in the idea of performing in an online space. One can take advantage of glitches and rely on modding if the game’s editors are not enough to achieve the intended results.

Matteo Bittanti: It is my understanding that Wolfpath.exe is your very first machinima. As you explained, the creation of Wolfpath.exe required the crafting of a scenario from scratch via the Far Cry 5 map simulation program. Can you elaborate on your production routine? How long did it take for you to achieve the desired outcome? And what kind of technical challenges did you encounter?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: Indeed, this was my first attempt at machinima-making. As I mentioned above, Far Cry 5’s map editor offers many options. By tinkering with the various menus, one can create a full movie set. But this program is intended specifically to design maps that can be played within Far Cry 5’s environments. The game has its own rules and conventions. It’s a first-person shooter and obviously, it wasn’t made for making films or anything artistic. This is why the standard camera was not enough for achieving the results that I envisioned. Before creating Wolfspath.exe, I spent some time playing with the editor just for the sake of it. I wanted to test the potential and limitations of this software. Somehow, I designed a forest map and I realized that it was the perfect setting for the events that I was planning to narrate. In Turkish mythology, there is a foundational story about how Turks discovered their motherland. According to the story, during an exodus from Mongolia, a group of wanderers encountered a grey wolf on a mountain road. As they followed the animal, they were led to a place behind the mountains and they settled where the wolf finally whelped. I wanted to recreate this story through a video game. The foggy woods I designed with this tool perfectly fit the story. In short, I became convinced that the software was versatile enough to create the weird landscapes that I’d like to use in my video.

Matteo Bittanti: How do you frame the connection between the fetishization of violence in popular video games such as Far Cry and real life situations? Do you find this relationship to be based on causation (that is, more guns in video games causes more violence IRL), correlation (that is, more guns in video games are just one of the factors that may explain the rise of violence IRL), or something else altogether?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: The fetishization of violence is mostly caused by the fact that mainstream video games simply mirror the dominant cultural values. Everyday life is still dominated by masculine values. Colonialism is pretty much alive and visible in daily interactions. It should not be surprising then if video games simply replicate masculine, colonialist, and capitalist values. They simply re-frame the dominant ideology within fictional contexts. A video game is basically daily life, but with gnomes and dragons and that’s about it. Video games are not at all an escapist medium: they simply validate the existing societal values. This is why I do not think that the violence that can be enacted in video games can lead to IRL violence. IRL violence does not need video games because it is already violent. What video games do is to simply normalize IRL violence. Digital platforms are a reflection of everyday life. The reason why social media like Twitter are a cesspool, an endless stream of sexist and racist insults, is that real life is sexist and racist.

Matteo Bittanti: In Wolfpath.exe, real life footage is embedded within a fictional situation. The television set is displayed on an altar: like a religious institution, it delivers “truths”. What role does television play in contemporary Turkish life? In 2013, during the Gezi Park protests, the current president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan famously accused social media platforms, and especially Twitter, of spreading lies and disinformation. What is the relationship between art, media, and politics, in your view?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: Most of the media in Turkey is under the direct control of the government. During the Gezi Park protests, Turkish citizens used social media platforms to mobilize and organize their protests. They relied on these back channels because the mainstream media was actively censoring their messages. This was part of a larger movement that took place in several countries around the world, including Egypt, Tunisia, and even Spain. It was not a “Twitter Revolution” as some argued obviously, but social media did play a role in supporting these protests. This is why the government was quick to denounce social media. They saw them as a threat. Ironically, the same media that were deemed democratic back then, today are used to spread populism, disinformation, and demagogy. Conspiracy theories, fake news, hate speech are amplified enormously by social media. Their spread is enhanced dramatically by these platforms. The admins do nothing to regulate or limit the circulation of this toxic content: they have no economic incentives to do so. On the contrary, the more people share these lies, the more profits they make. They specifically designed algorithms to facilitate the rapid spread of this filth. The more controversial the content, the richer Zuckerberg and the other techlords become. I am not confident that art can change this dire situation, to be honest. It is not powerful enough. However, it can lead to something. It can start a conversation, pierce holes in the shallow discourse of populism and help people to mobilize by creating shared experiences… On this point, I find the internet-based aesthetic movements and independent collectives valuable and promising.

Matteo Bittanti: In Wolfpath.exe, what do the singing street performers represent? And why is society so afraid of folk art?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: I took that footage from Istiklal Avenue. At that time, I was recording street musicians. Generally police don’t allow them to perform on that street. In the video I took, it is easy to see their anxiety while they are singing. After a short time, the policemen came and the performers immediately stopped singing and switched off their music in a hurry. For me, this apparently irrelevant episode is a symbol of fear of the repressive power of the state. When the two performers were singing and attentively looking around to spot an incoming threat, they were simultaneously performing the role of the watcher, the artist, the worker and the activist. To me, this is just an example of what the politicization of daily life looks like.

Matteo Bittanti: How are video games perceived at Marmara University, one of the oldest art institutions in the country? You are currently writing a dissertation on posthumanism and video game art. Can you provide additional details? It sounds very intriguing.

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: New media are welcome in this institution. Everything that can introduce new ways of looking at reality and making art is accompanied by excitement. Conservative artistic values are not popular at Marmara University. In my dissertation, I am analyzing video games as autonomous systems by looking at them from a posthumanist and new materialist perspective. Such an approach reconsiders the relationship between humans and machines by criticizing the central position of humans in regard to video game aesthetics and mechanics. I am also looking at artists who use video games as a medium of expression to identify recurrent strategies.

Matteo Bittanti: Masks play a key role in your practice. In many ways, the avatar performs the function of the mask: digital avatars are masks that players wear online. Why is the mask such a powerful symbol to you?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: Before I became interested in video game art I was into participatory art and researching about cross-border situations in rituals, folkloric games, and festivals. My participation projects were also mostly about identity shifting during ritualistic organizations. Ritual and masks cannot be considered separately. When you wear a mask you change your identity and this comes along with deconstruction of the previous identity you have. Identity, body and mutual transformation are still so interesting subjects for me. Masks and avatars are perfect elements to bring these subjects to the surface.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe your new experimental movie The Past Is An Alien Planet? What role does the video game imaginary play in creating fictions and ideas about the future?

Kadir Kayserilioğlu: My latest movie The Past Is An Alien Planet takes its name from a chapter in Mark Fisher’s Ghosts of My Life. Once again, I designed an island by using Far Cry 5’s map editor. The island is decrepit and completely overwhelmed by wildlife. The result is both anachronistic and chaotic: the elements depicted in the landscape do not really fit together, timewise. For instance, there’s a helicopter wreck next to the skeleton of a mammoth on the beach. The video proposes an analogy between my childhood memories and future satellite networks, specifically Elon Musk’s Starlink. The narrative starts from this point and evolves from there by introducing alien phenomena. I am using frameworks derived from popular culture, disaster theory, ecological thinking, urban transformation and more esoteric theories, like the architecture of coincidences. Video games were ideal to illustrate such a narrative. By combining real life footage and video games imagery I built a non-linear narrative where reality and virtual reality merge. For my future projects, I would love to work on a story about conspiracy theories and internet based communities. I’ve been brainstorming about these themes for a while. I will probably use video games aesthetics for my next project as well.

WOLFPATH.EXE

digital video (1920 x 1080), color, sound, 4’ 04”, 2017, Turkey

Created by Kadir Kayserilioğlu, 2017

Courtesy of The Pill and Kadir Kayserilioğlu, 2022