Even Asteroids Are Not Alone

digital video, color, sound, 17’, 2019, Iceland

Created by Jón Bjarki Magnússon

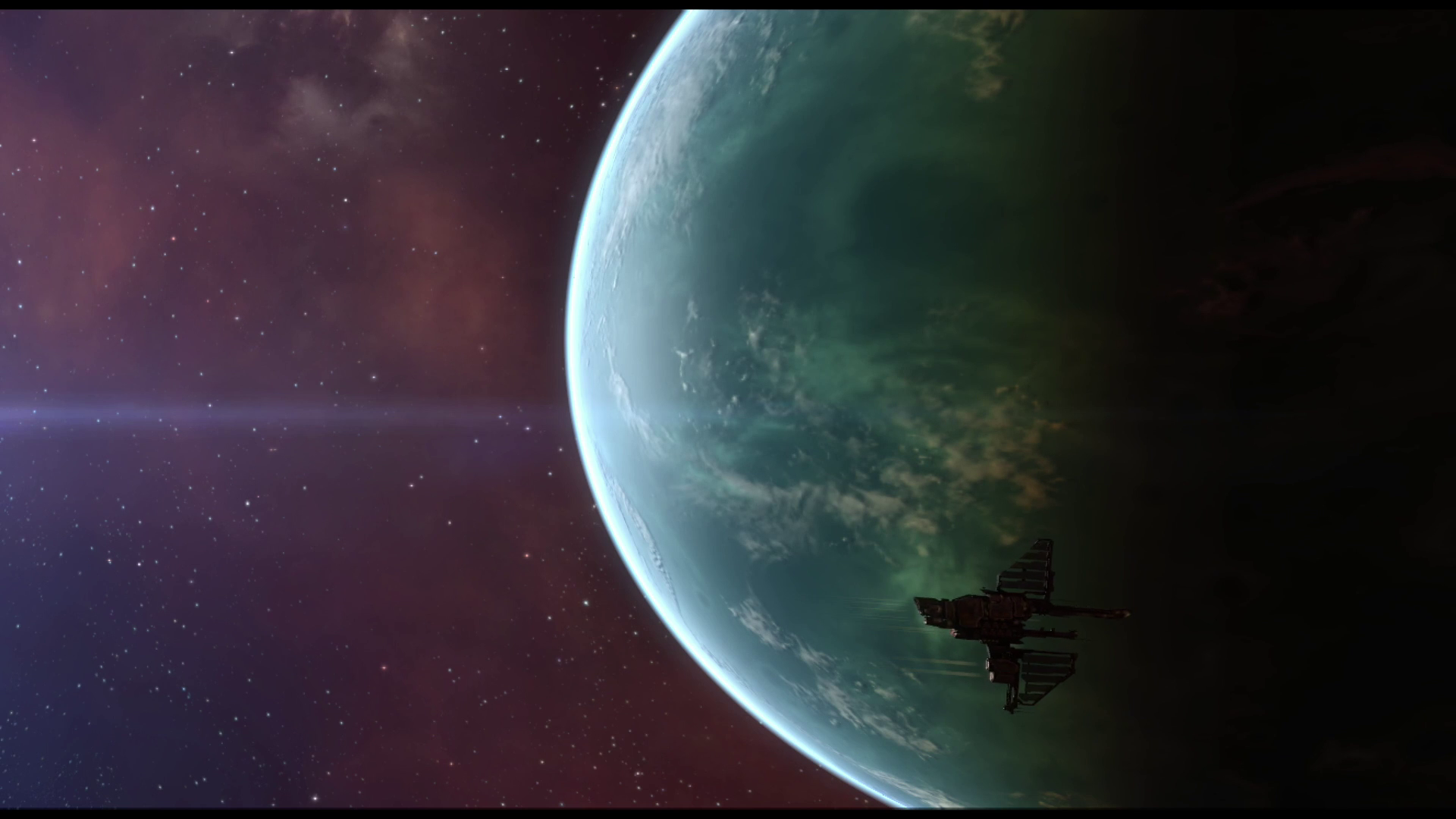

In the vast and hostile world of New Eden, trust is not a given. How can one make friends in the depths of space? Even Asteroids Are Not Alone explores social relationships within Eve Online, a multiplayer game where hundreds of thousands of players mine, trade and fight their way through computer-generated galaxies far away from the world as we know it. By weaving together the experiences of fourteen individuals from around the globe, the filmmaker shows a different story: The ability of online games to forge communities and bridge the space between people, countries, and continents. Entirely shot within Eve Online, Even Asteroids Are Not Alone is an insightful ethnographic video game essay.

Jón Bjarki Magnússon is an award-winning journalist, writer, and filmmaker from Iceland currently living in Berlin, Germany. He studied Creative Writing at the University of Iceland in 2009-2012, published a book of poetry ― The Lambs in Cambodia (and you) ― in 2011, and received a Master of Arts in Visual and Media Anthropology at Freie Universität, Berlin. Even Asteroids Are Not Alone was his first film, followed by Half Elf (2020), a feature length documentary. Even Asteroids Are Not Alone won the RAI and Marsh Short Film Prize at the RAI Film Festival 2019 and was screened internationally at several festivals, including Transmediale.

Matteo Bittanti: You have a background in journalism and poetry and Even Asteroids Are Not Alone is both a poetic account of bonding through gaming and a very detailed deconstruction of a gaming phenomenon that avoids the usual tropes and clichés (e.g. violence, addiction etc.). Can you describe the process of creating Even Asteroids Are Not Alone? How long did the entire process take, from pre-production to post-production?

Jón Bjarki Magnússon: Computer games and virtual worlds are often portrayed as places of social isolation and those who dwell in them regarded as anti-social. By collecting the experiences of the players themselves I wanted to tell a different story on the ability of online games to forge a strong community and bridging the space between people. I started my research with a very simple question: How does one make a friend in (this) space? And then literally travelled through space for weeks on end, got myself “hired” at one of the corporations in-game and got to know the people by playing and working with them. I made friends that welcomed me into their clan and were ready to share their stories with me.

The whole process, from the point of preparation to finishing and post producing the final cut, took me about three months, while most of the interviews were conducted within the time frame of about one month. I would start with coding the interviews looking for the most common patterns I found in the players stories with the focus on a shared experience rather than an individualistic one.

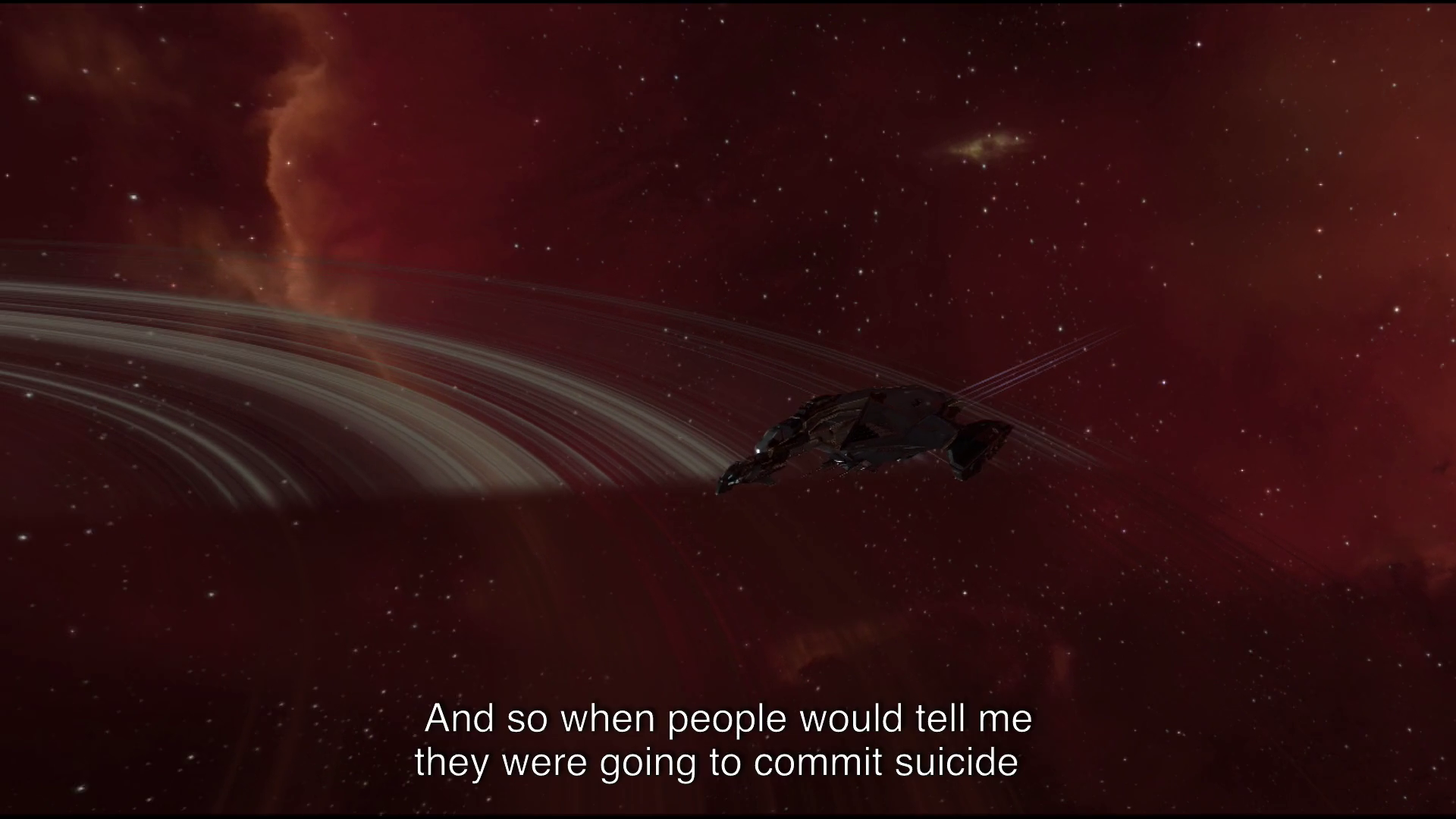

As the soundscape of their voice overs became clearer I would start my video work, which mainly consisted of traveling between solar systems looking for ideal shots that had the ability to portray the vast world the players inhibit. I would gather screenshots of the planets, space stations, asteroids belts and the general landscapes that made up the world of many of my interviewees. I would record other corp members’ spaceships at work such as when we were mining asteroid belts, but I would also record my own character when flying different spaceships and use that imagery to portray the action of flying in the game.

Matteo Bittanti: The project began as a study in digital anthropology during the Masters program of Visual and Media Anthropology at Freie Universitat Berlin. What authors and/or texts inspire you to pursue such an investigation? What do you find especially remarkable about the game’s community? How did you approach these fourteen individuals? And why did you choose the medium of machinima?

Jón Bjarki Magnússon: I came into the MA program from a background in newspaper journalism and creative writing, so my knowledge of visual storytelling and/or anthropology was limited. Learning about the rich history of ethnographic filmmaking and reading about all the different ways anthropologists use to imbed themselves in the communities they research, inspired me to search for ways to experiment with methods such as participant observation, where the researcher himself takes full part in the activities of the people being researched. I felt that an online game and/or a virtual world would be the perfect setting for such an investigation, especially for someone who was so new to the field. I was already familiar with Eve Online, had played the game on and off since its release in 2003, and knew about the strong community bonds that can be realized through the cooperation of players.

I have to admit that I was a little bit hesitant in the beginning, having not played the game for years it took some time to get used to the game mechanics again, and then I was not quite sure what would be the best way to approach people to get them involved in a project like this. But as soon as I forced myself to reach out to people, both through Eve Online’s Facebook page and in game, things started to happen fast. I was invited to join a corporation and do missions with players that were more than willing to help me in any way possible. I would say that having such a “home base” was the perfect starting point for a research like this. My fellow corp-members showed a lot of understanding in the project, were willing to answer any of my questions and more than eager to connect me with other players in different parts of the world. This reassured me in the belief that the community aspects of the game were still as strong as they had been when I was playing some years before, and made me more dedicated in the search of finding the best possible way to portray these elements.

The medium of machinima felt like the most logical step to do this. Here I was documenting the connections that people made in a computer-generated space world, and what better stage for such a film than the planets, moons and nebulas of New Eden itself? By purely focusing on the visuals of the game I wanted to give the spectators a taste of how it is to fly through this world, a feeling for its vastness, hoping to build a bridge between the players themselves and those not so familiar with online gaming. Perhaps a common language of some sorts, a simple meditation on friendship in space.

Matteo Bittanti: The film’s focus is on the communal aspect of the game, rather than the game itself. In fact, the documentary says very little about Eve Online, but by the end, the players’ identities become very recognizable. Can you describe the rationale behind the documentary structure, especially the articulation in chapters and the use of voiceover?

Jón Bjarki Magnússon: I would look for similar patterns within the interviews I took looking for a communal voice rather than an individual one. The players describe how their quest for beauty, freedom and adventure in a virtual space exposed them to an enriching social environment where the logic of friendship remains the same as in real life. Here trust is built over time. The game mechanics force them to interact with each other. By banding together in corporations and helping each other out, they gain greater opportunities. Through communal practices such as mining or fighting, their bonds grow stronger. What starts with a chit-chat about in-game stuff slowly evolves into intimate conversations about real-life issues in general. Often referring to their in-game friends as family, the players describe everlasting friendships that have had life and death implications reaching far beyond the game itself.

The structure of the film is mainly built around this progression of human connections within the game world. The first part (New Eden) is mainly concerned with introducing the viewer to this new world, what it is about, why people are here and what they are doing. The second part (Diogenes) deals with how people first make contact, how conversations start and in what settings etc. It is not until in the third and last part (The Space Pope), that we learn about how deep these bonds of friendship really go. What I came to realize is that the core of most of these stories were not only about this game per se, but more broadly about human communication and interaction in general, something that could actually be attributed to many other settings. I started to feel that the film I was making might not necessarily be about Eve Online per se, but rather about online communities in general. The longing for understanding, connection and someone to share experiences with is universal. It doesn't matter whether the space we are flying through is virtual or physical, we are all just looking for some companionship during the ride.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe your own relationship to video games? I read that you were already familiar with Eve Online before you began shooting this documentary. Why did you pick this game in particular as the subject of your investigation? Do you see yourself working again with video games in the future, and thus machinima?

Jón Bjarki Magnússon: We did not have a computer at my home until I was about twelve years old. Prior to that my only experience with computer games had mainly been at my friends houses and/or when some of them were nice enough to lend me their Nintendo. However, during my teenage years I would play quite some games, such as Command and Conquer: Red Alert, Starcraft, Commandos, Fallout and Half-Life to name a few of my old favorites that come to mind.

I was seventeen when the (Icelandic) developers of Eve Online visited my high school in 2001, two years prior to the games release, to share bits and pieces of the digital world they were in the midst of creating. The beautiful images from outer space caught my eye, the idea of roaming these distant lands while communicating with actual people stuck with me. For someone a bit bit bored of suburbia life this world sounded like a great escape. When I was finally able to set foot into the world of Eve in the spring of 2003 the buzz had mostly worn off. It was true that their world was huge and the possibilities endless, but I was now occupied with other things. I did however play the game a little bit on and off ever since, always admiring its potential to connect people, although I would not say I have been a very serious player.

I could see myself working with video games in the future, and actually think that combining machinima style filmmaking with a more conventional documentary approach would be something worth doing, but I am not planning anything like that at the moment. I only recently finished my second film, Half Elf, about a 99 year old lighthouse keeper that prepares his earthly funeral while trying to reconnect the elf within, and will now take some time off to think about possible next projects.

Even Asteroids Are Not Alone

digital video (1980 x 1080), color, sound, 17’, 2018, Iceland

Created by Jón Bjarki Magnússon, 2018

Courtesy of Jón Bjarki Magnússon, 2020

Made with Eve Online (CCP Games, 2003)