COLOSSAL CAVE ADVENTURE – THE MOVIE

Digital video (1024 x 1024), sound, color, 55’ 33”, 2022, Germany

Created by Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig

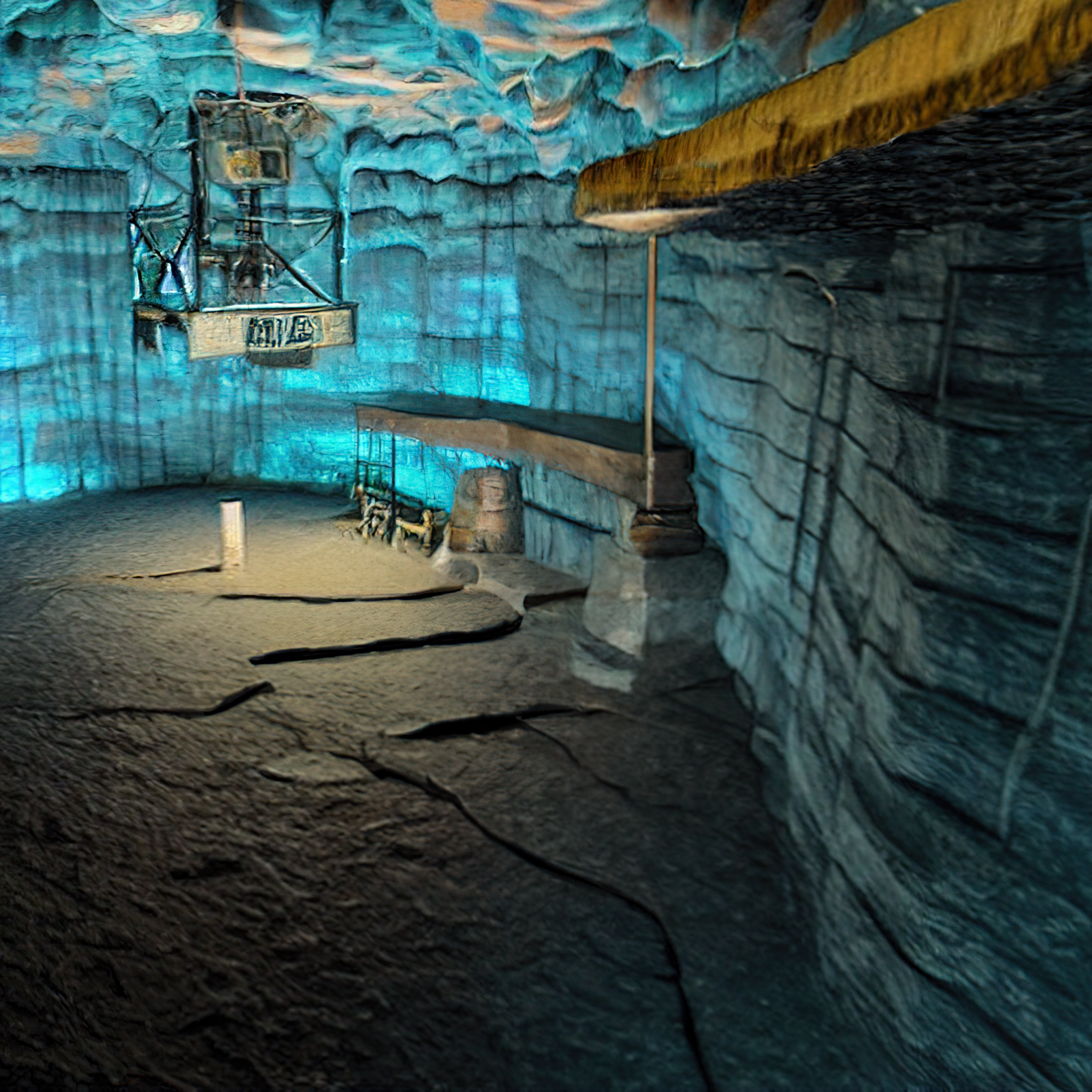

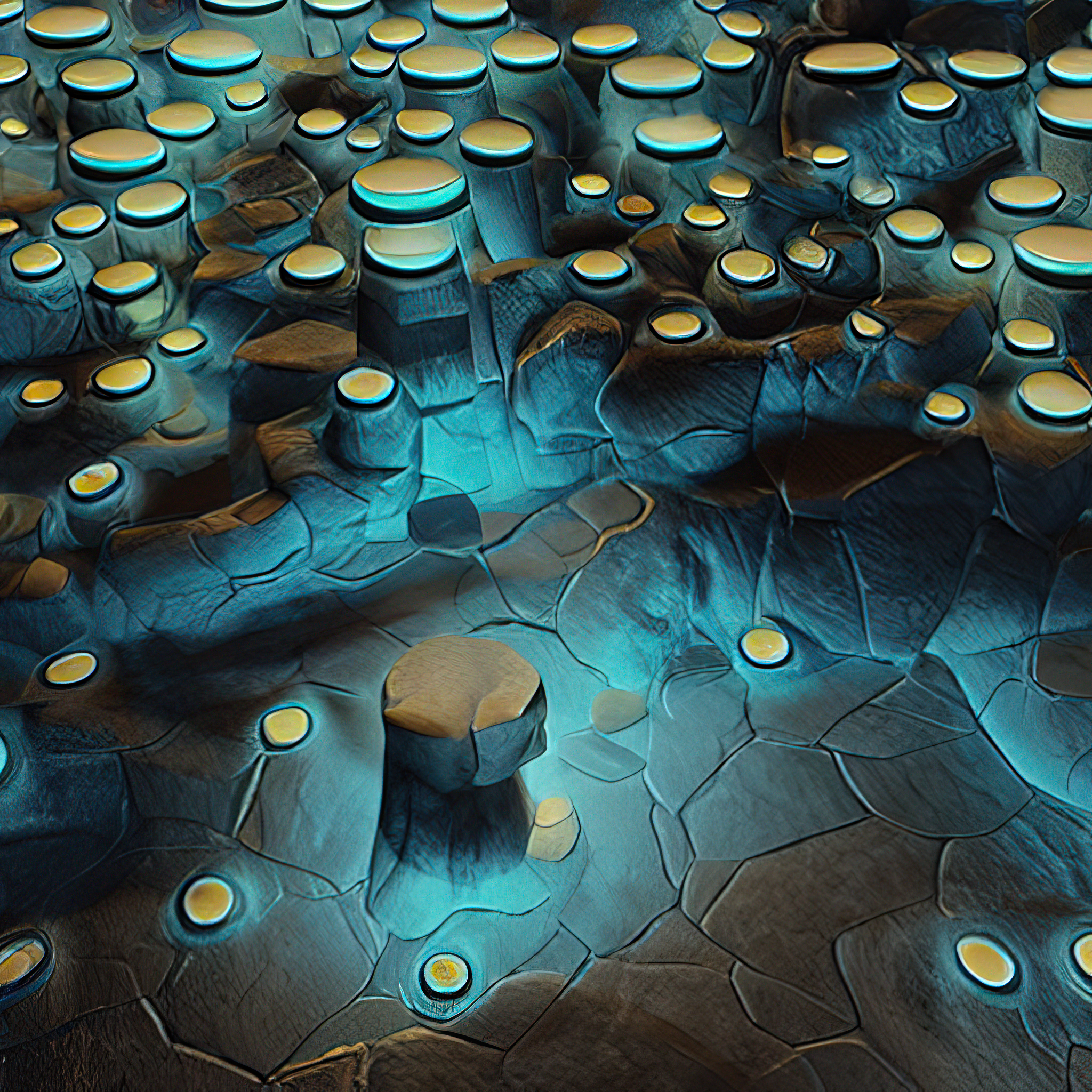

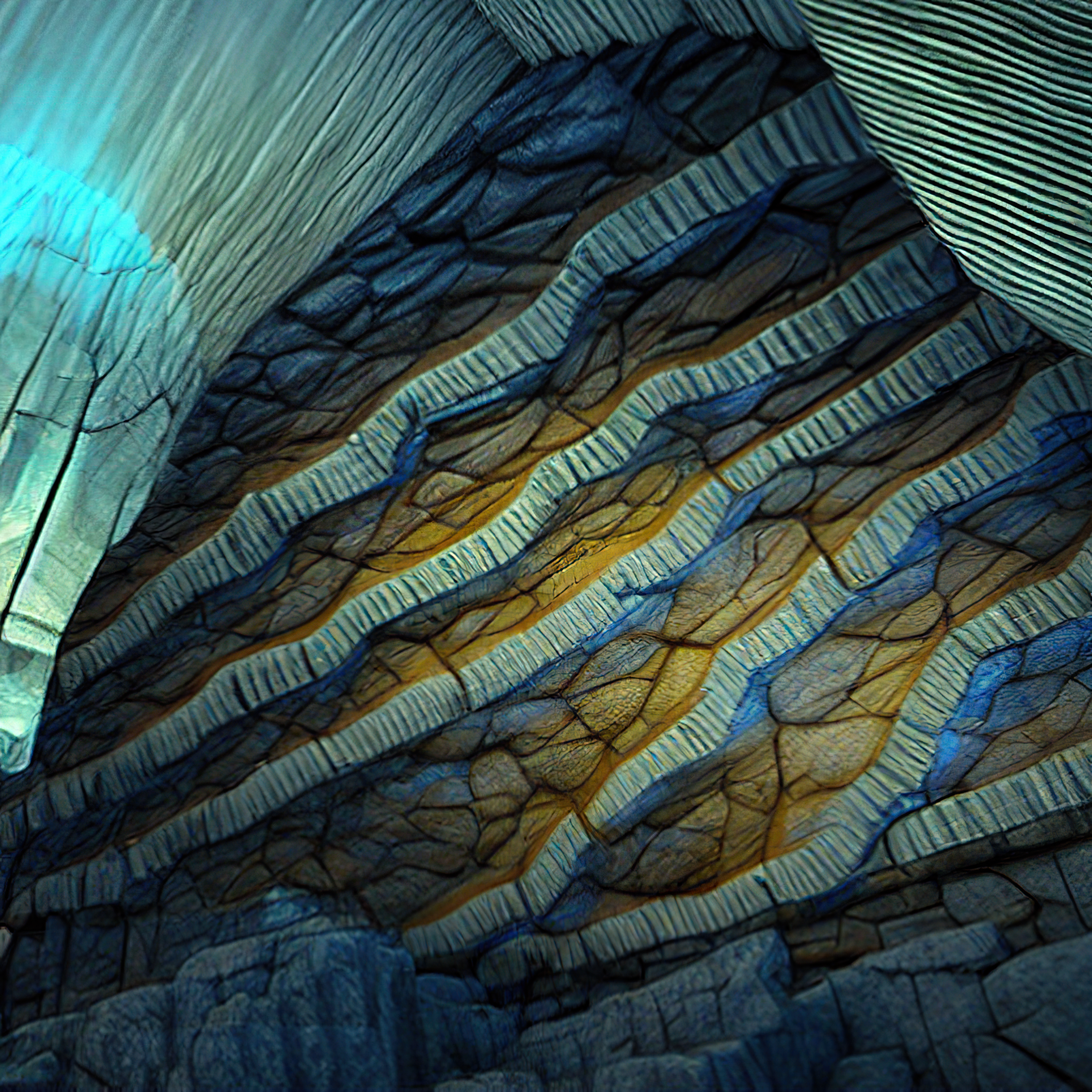

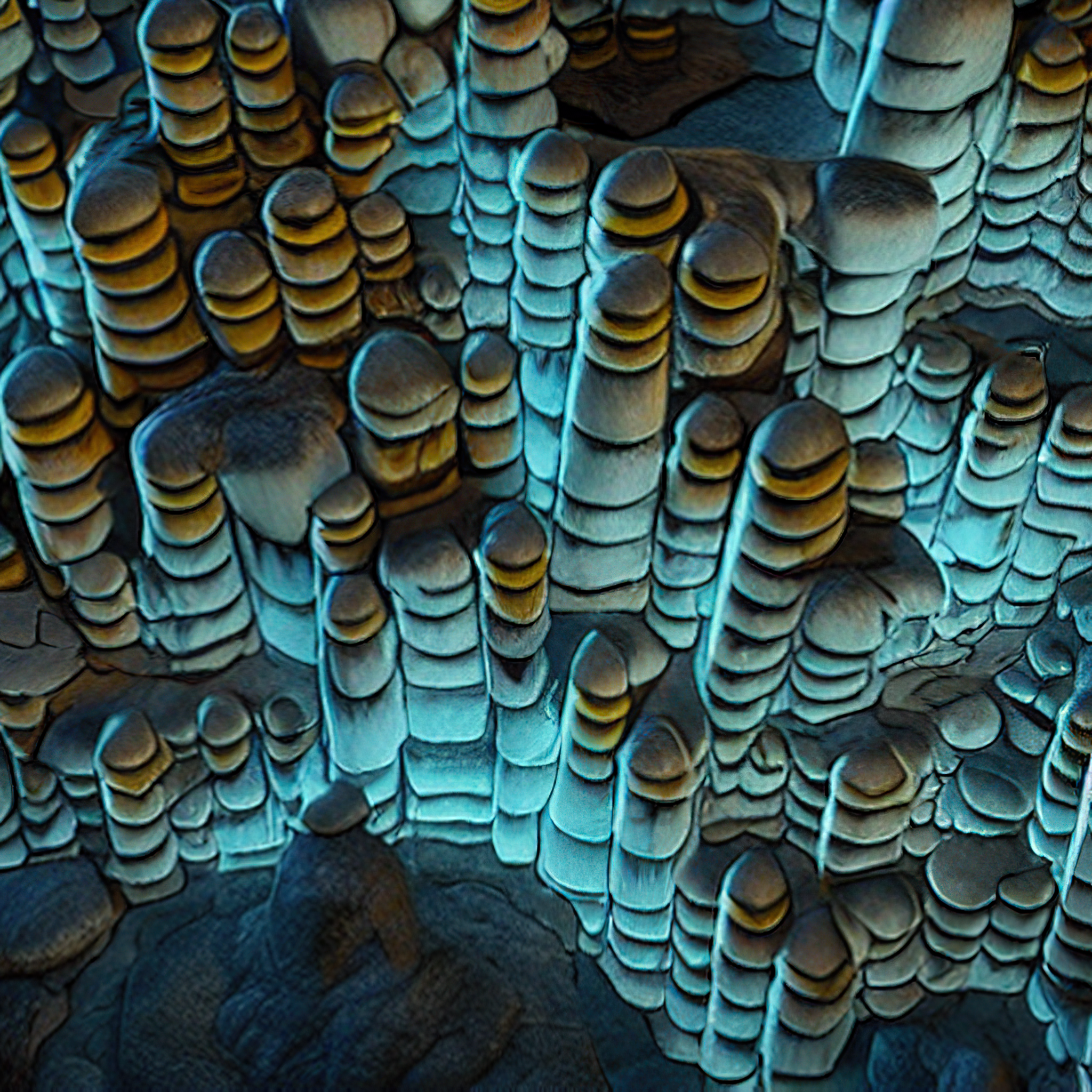

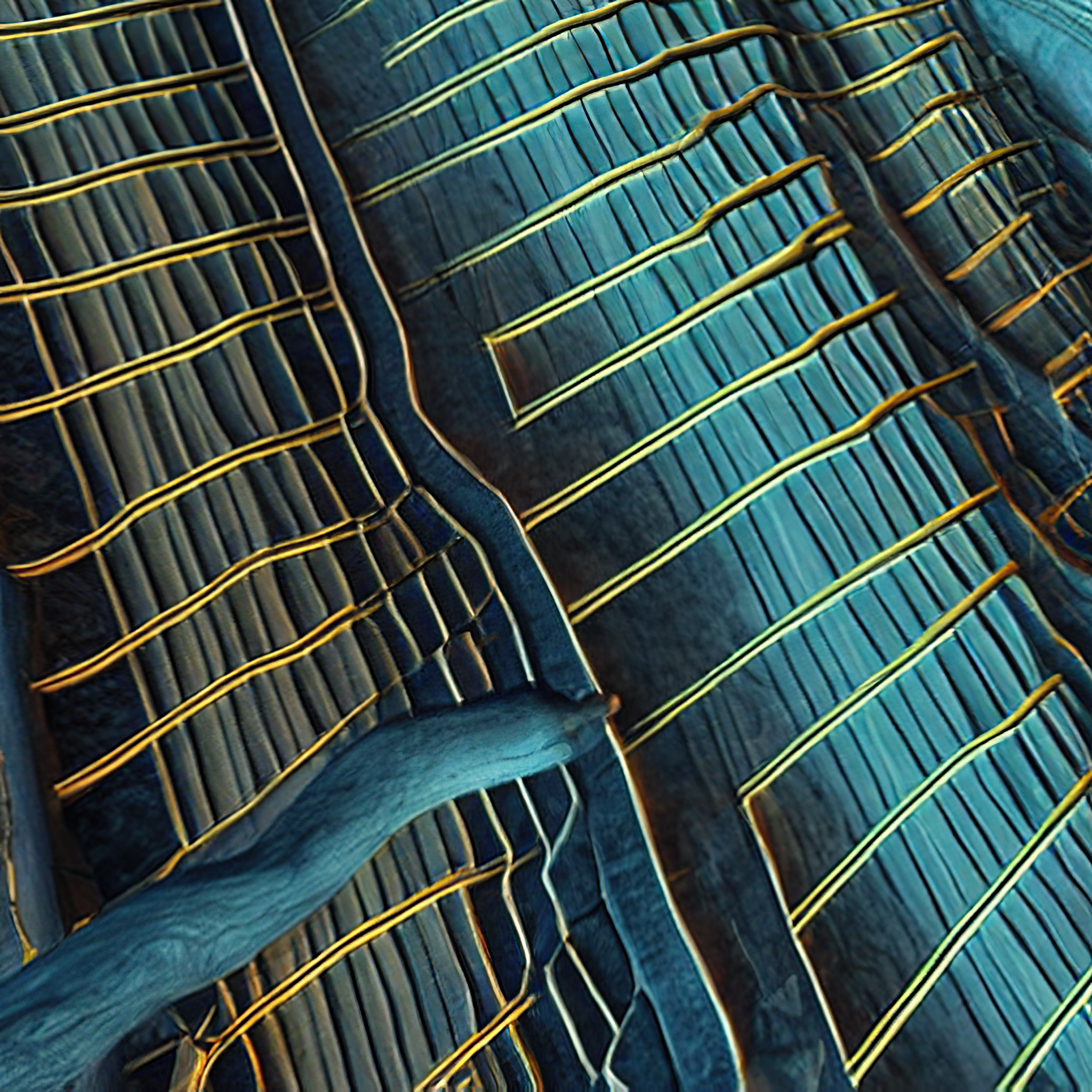

An adaptation sui generis of an early text-based adventure games, Colossal Cave Adventure - The Movie remediates the program developed by Will Crowther in 1976 based on the architecture of the Mammoth Cave complex in Kentucky. The original game used text to describe the environment whereas the animated film uses AI-generated visuals. Every eight seconds, the AI system receives a new textual description, taken from Colossal Cave Adventure’s source code, comprising 379 inputs ranging from narrative descriptions of nature to jargon from the vocabulary of speleologists to single words meaning an object, a compass direction, or an exclamation. The camera constantly moves downwards, digging through geological layers and exposing new cave spaces again and again.

Born in 1977 in Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, Thomas Hawranke is a media artist and researcher whose practice investigates the influence of technology on society and the impact of computational logic onto human-animal-machine relationships. In his eclectic interventions, Hawranke operates at the intersection of performance and video art: a central concern of his is bringing to the surface the ideologies that inform everyday life. Hawranke graduated in Media Art at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne and received a PhD from the Bauhaus-University in Weimar, Germany, with a dissertation on the modification of video games, also known as modding, as a method for artistic research. Since 2005, he has been a member of susigames, an independent art label founded in 2003 that investigates alternative gaming’s approaches, and he is the co-founder of the Paidia Institute in Cologne. His works have been presented at several exhibitions and festivals, including the zkm_gameplay in Karlsruhe and the RENCONTRES INTERNATIONALES PARIS/BERLIN. Hawranke lives and works in Cologne, Germany.

Lasse Scherffig is an artist and scientist with a background in cognitive science/machine learning and computer science. Scherffig is interested in the relationship of humans, machines, and society; cybernetics and the technological infrastructures of communication and control; and the cultures and aesthetics of computation and interaction. His work oscillates between computer science and experimental artistic practices, engineering and amateur/DIY methods, science and humanities. A professor of Interaction Design at Köln International School of Design, he previously served as the Department Chair of Art and Technology at San Francisco Art Institute, where he taught as assistant professor. Scherffig co-founded the artist group Paidia Institute and off topic, magazine for media art. His art projects have been shown at numerous exhibitions. Lasse holds a doctoral degree in Experimental Computer Science from KHM, Academy of Media Arts Cologne.

Matteo Bittanti: Colossal Cave Adventure – The Movie is both an exercise in media archeology and an experimental take on AI. In other words, it is very now. It speaks of the contemporary moment like very few other recent artworks. It goes back to the textual nature of Crowther’s game, using AI-generated visuals to generate an animated film, giving new life (and form) to a seminal project. Can you articulate your intentions and rationale behind Colossal Cave Adventure’s facelift, no pun intended?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: Colossal Cave Adventure has long been of interest to us as it is discussed in-depth in Claus Pias’ Computer Spiel Welten (2002). Here, Pias lays out how it is connected to both the practice of speleology and to the Dungeons and Dragons community. He also shows in detail how Crowther has been involved in creating the very foundations of today’s Internet infrastructure: Crowther was responsible for writing algorithms for dynamic routing on the Arpanet and at the same time for hiding routing decisions from network users – a problem paradoxically labeled “transparency.” Remarkably, Crowther started using his workplace computer at BBN (Acronym of Bolt, Beranek, and Newman, a Massachusetts company that played an important role in early computing history, Ed.) to record the topology of Mammoth Cave after his wife, the physicist Patricia Crowther, had found the “muddy passage” that connects the Flint Ridge and Mammoth Cave systems, a major breakthrough in the effort of mapping the caves of Kentucky. After separating from his wife, Crowther was no longer able to visit the cave and instead he started to “fool around and write a program that was a re-creation in fantasy of my caving [...]. My idea was that it would be a computer game that would not be intimidating to non-computer people” (Pias, p. 120). Crowther, you could say, invented the adventure genre while appropriating his wife’s work and mis-using an early computer system as well as his knowledge of ARPANET routing and not intimidating people through “transparency.”

In contrast to this history, which emphasizes the role of technology, Alenda Y. Chang in Playing Nature. Ecology in Video Games (2019) has pointed out the role of language through which the game communicates. The language of the game here is seen as an amalgamation of descriptions of materiality, cave terms, and the topology of the actual cave. All of these, she argues, creates a form of “environmental realism” resulting from the conformity of the game world and the player’s ecological context. It is this focus on realism-through-language that is of interest to us, as it bridges the worlds of “old” and “new” artificial intelligence – from 1960s ELIZA to contemporary systems like chatGPT. Chang points out that “Compared to current games, in which player identity is most often grafted onto a three-dimensional avatar in a curious blend of first-person belief [...] and third-person witnessing [...], Adventure is unusual in its interposing of an AI between player and environment” (Chang, p. 27). (note 1)

Matteo Bittanti: Claire Evans provides a counternarrative of the creation of Colossal Cave Adventure in her excellent book Broadband. In chapter six, titled “The Longest Cave” , she argues that Crowther wrote the game for his youngest daughters as a way to connect with them after the divorce – they loved the game. In other words, Colossal Cave Adventure is described as an intergenerational bridge, technicity is affectivity: “archeology is always anthropology”. In the same chapter, Evans also cites Mary Ann Buckles, who’s been recognized as a pioneer of game studies. Buckles, “compared the game to folktales, chivalric literature, and the earliest uses of film”. Beyond the scope of this project, what is Colossal Cave Adventure to you?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: To us, Colossal Cave Adventure is a fascinating boundary object, in the sense of Susan Leigh Star. It encompasses the worlds of computer gaming, environmental text and fantasy literature, network infrastructure, artificial intelligence, professional speleology and amateur caving, RPGs, and Crowther’s family biography. We like to see it not as the first text adventure, but rather as an opportunity to acknowledge its complexity and to explore the discourses it entails.

Matteo Bittanti: I am very interested in your process. Can you describe the technical aspects of this astounding project? What kind of challenges did you encounter? I’m also interested in the ratio: was the square format (1024 x 1024) somehow dictated by the AI-generative system or was it your choice?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: Generating a film of this length and resolution only was possible because we had access to a computer cluster through a research project on AI and design. The cluster is relatively small but still provides more computing power than your average gaming GPU. Stable Diffusion (that is its first release, which we worked with) works best with square images, ideally of size 512 x 512. The reasons for this lie in the structure of the software frameworks and GPU hardware used for the complex math of running the neural networks. The aspect ratio of the film thus reflects the technology it was made by. The images we generated started out with 512 x 512 pixels and were subsequently upscaled using another neural network.

Matteo Bittanti: In the artwork description, you write that “Every eight seconds, the AI system receives a new textual description. These descriptions are taken from Crowther’s source code from Colossal Cave Adventure in 1976, which contains a total of 379 inputs ranging from narrative descriptions of nature, to jargon from the vocabulary of speleologists, to single words meaning an object, a compass direction, or an exclamation.” Does that mean that there is not a single Colossal Cave Adventure - The Movie but potentially infinite videos since the textual descriptions that the AI receives from 379 inputs ranging can be randomized? Also, will all these possible videos change visually as well as the algorithms improve? If so, is it correct to say that you could potentially make an infinite number of Colossal Cave Adventure movies? Or, rather, that Colossal Cave Adventure would remake itself endlessly?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: Yes! It is even more complicated than that, because the very same sequence of prompts that we used can yield an enormous number of different images for each prompt – depending on the noise the denoising process starts with, the number of denoising steps, the motion of the virtual camera etc. On the other hand, the resulting images will always be shaped by the cultural memory encoded in the stable diffusion model which picks up the textural and compositional invariants of billions of images. So, if Colossal Cave Adventure would remake itself endlessly, these remakes will always be variations stemming from the same visual language. Interestingly, every new iteration of models like Stable Diffusion or OpenCLIP devour billions of images scraped from the internet, possibly including images generated by their precursor models. In this sense we might really be talking about remaking and digesting itself.

Matteo Bittanti: The inevitable corollary: Who is the intern did viewer of Colossal Cave Adventure – The Movie? A human or a machine? Both? None? I would like to clarify that my question is not polemical or critical in any way: I am genuinely wondering if your project, – as well as other recent films generated by AI-tools – is the vanguard of a new generation of machine-made storytelling intended for humans, whose attention span is generally short, or truly experimental and unclassifiable, sa in qualitatively different from “conventional” cultural products that circulate in cinemas or on streaming platforms. What is your intended or ideal display setting for Colossal Cave Adventure – The Movie? Did you conceive it as an installation? Is it meant to be screened in an auditorium like space? Is its “natural” habitat a website?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: The project deliberately slows down the process of generating and consuming countless images that has been started by generative AI tools like Stable Diffusion or Midjourney. We intend to facilitate a meditation-like experience, embodying Crowther the caver ingesting the atmosphere of Mammoth Cave – albeit through the lens of the contemporary Internet. In this sense it is human-centered with an awareness for the non-human surrounding us. Ideally, it would be shown on-site, projected in the Hall of the Mountain King inside Mammoth Cave, where the soundtrack would be the noise of the actual cave.

Matteo Bittanti: If I understand that correctly, you are describing a situated, slow cinema experience, merging the natural and the technical. Have you considered an interactive version of your AI-based remake of Colossal Cave Adventure, by any chance?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: This is currently being done by Roberta and Ken Williams, famously known for the Sierra on-line adventures. This won’t be an AI-generated game, however, there definitely will be many AI-based games in the future, first ones that use AI-generated assets and later ones that use images that are generated in real-time. Personally, we are not so much interested in treating AI as a tool for game-making but rather using AI to probe the techno-cultural history of the Global North with all its flaws and blind-spots. In addition, we are interested in questions of visuality, representation of ecological processes, and automation and codification of culture.

Matteo Bittanti: Based on your experience with Stable Diffusion Public Release, what do you expect from future updates? And what is next for AI-generated visualization?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: Fabian Offert has recently proclaimed the end of AI art in a talk at Hidden Layers, arguing that before prompt-based image generation, generative images often structurally and thematically addressed their own technological condition whereas now image generation is becoming about something else. In that sense, we are currently trying to find out what that something might be. One trend we observe is that images may become less important while their conceptual context may gain importance, e.g., it will be less about pixels and more about prompts. From our perspective, developments in language-centric AI and the latent spaces of word embeddings have long been more interesting than the area of image generation. With systems like chatGPT, the language part of AI will, again, profoundly change and in turn impact image generation. Dealing with AI suddenly resembles the “extensive linguistic negotiations” between player and Colossal Cave Adventure observed by Chang (p. 27) (note 2). Offert, at another occasion, has called this the upcoming age of ‘humanist’ hacking”.

Matteo Bittanti: Is the accompanying sound also generated by the AI?

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: What we hear on the audio layer are short field recordings from different caves that are played through a hardware sampler which is hooked up to a guitar-pedal stereo reverb effect. The playback of sounds like stones falling and cracking or water dripping and flowing are semi-randomly automated, creating a generative ambient soundscape for the images. The reverb acoustically defines the size and volume of the cave. This is meant to lure the viewer into the stream of images and tries to reenact the experience of the hermit in the cave, as a “re-creation in fantasy” of Crowther the caver.

Matteo Bittanti: Colossal Cave Adventure was, from its inception, a highly collaborative, participative project. As Evans writes in Broadband, “An Adventure devotee at Stanford, Don Woods, modified the code further by adding fantasy elements — an underground volcano, a battery-dispensing machine — to Crowther’s austere descriptions.” (p. 76) You are engaged in this process of rewriting and augmentation as well, through the aid of an AI-based tool. In his book New Dark Age (2019), James Bridle argues that now that “advanced chess” - i.e. the human players and machines playing together, as a team (note 3) — has become a de facto standard in professional chess competitions, we should expect the same for most fields of human creation, including art. In other words, Bridle argues that, rather than replacing human creativity, AI’s real strength lies in its ability to complement, expand, and augment it. Do you agree with him? It seems to me that your own project validates that claim…

Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig: The dream of human-machine collaboration is as old as digital computing itself, for instance formulated in J.C.R. Licklider’s “Man-Computer Symbiosis” (1960). In this vision, computers execute the tasks that are hard for their operators — calculating data, plotting graphs or, today, generating images — while their operators “set the goals and supply the motivations” (or, today, create prompts and curate images). The problem with this idea is that it hinges on the question of automation: What tasks can be automated and how? Looking at the output of generative AI systems, we have the feeling that we can automate whatever has been standardized. The question of creativity thus becomes complicated. On the other hand, any work with technology decenters human agency and everything created with a computer has been co-created.

Notes

1) Full quote: “Compared to current games, in which player identity is most often grafted onto a three-dimensional avatar in a curious blend of first-person belief (“I am the military operative on this mission”) and third-person witnessing (“That is my character moving around on the screen”), Adventure is unusual in its interposing of an AI between player and environment.”

2) Full quote: “In a mode reminiscent of the orthodox Cartesian dualism between mind and body or philosophy’s brain in a vat, the player issues commands to her physical extremities and waits patiently to see if the commands are understood and acted upon; garbled commands lead to extensive linguistic negotiations, as the player searches for objects and actions that the program can recognize.”

3) Full quote: “Cooperation between human and machine turns out to be a more potent strategy than the most powerful computer alone. [...] While machine intelligence is rapidly outstripping human performance in many disciplines, it is “not the only way of thinking, and it is in many fields catastrophically destructive. Any strategy other than mindful, thoughtful cooperation is a form of disengagement: a retreat that cannot hold” (p. 173).

COLOSSAL CAVE ADVENTURE – THE MOVIE

Digital video (1024 x 1024), sound, color, 55’ 33”, 2022, Germany

Created by Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig, 2022

Courtesy of Thomas Hawranke and Lasse Scherffig, 2023

Made with Stable Diffusion (CompVis group LMU Munich; Runway; Stability AI, 2022)