Blood Paintings

digital video, color, sound, 11’ 06”, 2024, Australia

Created by Georgie Roxby Smith

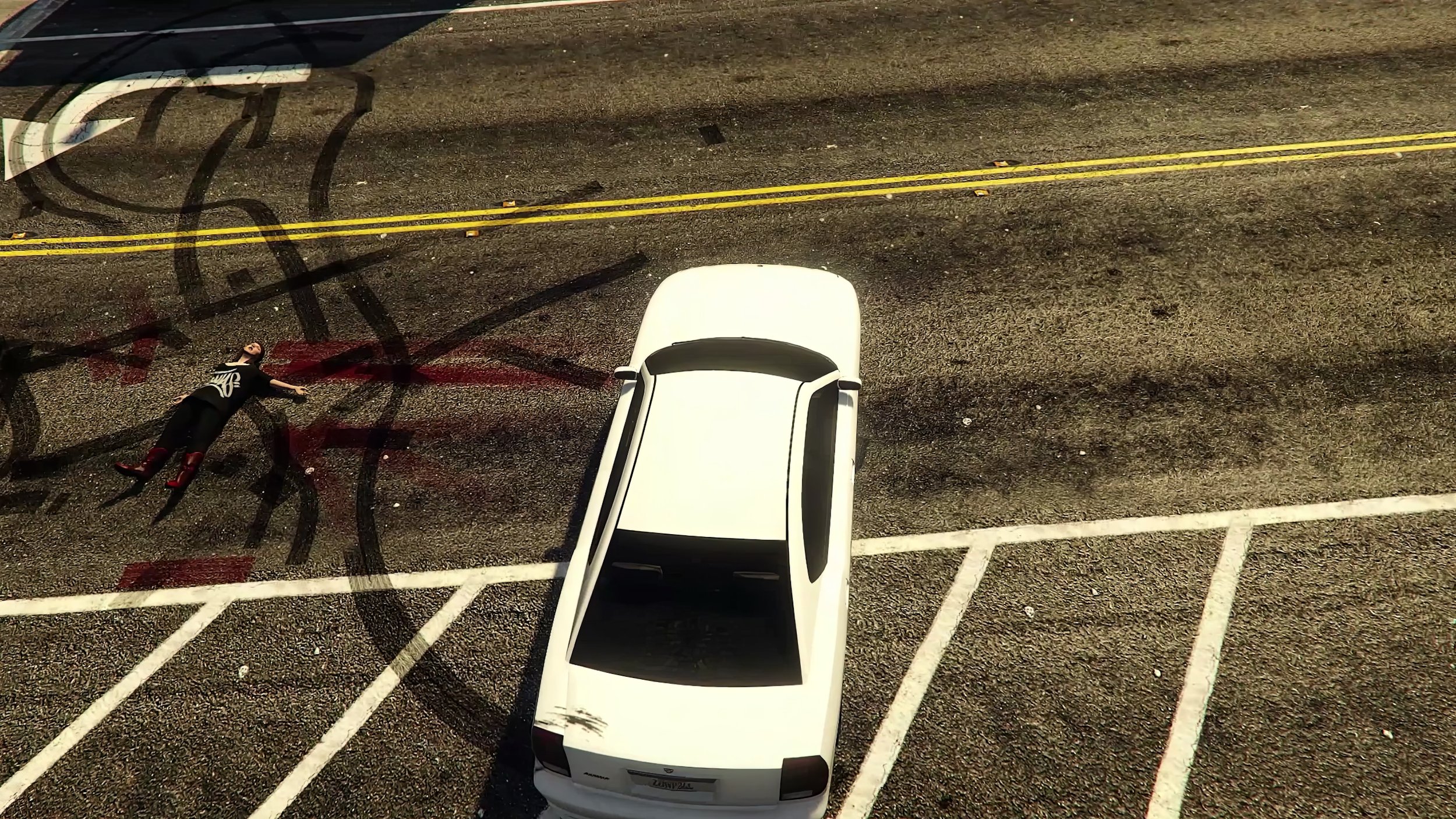

Georgie Roxby Smith’s Blood Paintings series merges digital gaming spaces and physical art. Each piece comprises three distinct components: a machinima documenting repetitive violence against GTA V pedestrians, intimate selfies showcasing the finished abstract paintings that violence yields, and hybrid digital/physical prints combining in-game imagery with organic artistic styles. This unique, multi-format presentation offers insight into both the meticulous creative process and the provocative contrast between clinical virtual acts and tactile human artistry.

Georgie Roxby Smith is a pioneering digital artist who uses gaming, AI, video, and performance to probe modern identity and reality. Her work focuses on representing marginalized groups, especially women, in online environments. Artworks like The Fall Girl and 99 Problems [WASTED] expose violence against female video game characters, critiquing the misogyny embedded in gaming worlds. Smith’s bold, confrontational, socially-engaged art has exhibited globally and earned prestigious grants and residencies. As virtual and actual boundaries blur, her practice reveals hard truths about identity and systemic bias persisting digitally. Blending emerging tech and mass media, Smith dispels notions of liberation in our increasingly visual world. Her immersive works harbor the probing questions that will propel digital art to its next avant-garde evolution.

Matteo Bittanti: You have an extensive background working with emerging technologies and confronting complex themes through socially-engaged digital artworks. Since completing your MFA in 2011, your practice has focused intensely on issues around representation and marginalization in online spaces, particularly violence against women in gaming. Could you tell me a bit more about what initially drew you to work at the intersection of technology, identity, and activism in your art? Was there a specific experience or revelation early on that shaped your desire to harness new media to tackle provocative questions around gender, embodiment, and systemic prejudice persisting into the digital sphere and the virtual imaginary?

Georgie Roxby Smith: Reflecting on my journey, it’s clear that a pivotal moment was my reengagement with the gaming world after a significant hiatus. When I returned, I was immediately struck by the profound evolution of video games – they had transformed into immersive, cinematically rich experiences. However, this seductive transformation was juxtaposed with a troubling reality: the persistent misogyny and the narrow representations within these virtual spaces.

This was particularly evident in MMOs, where the aggressive tone of conversations and the marginalisation of women’s voices was blatant. These experiences were not just isolated incidents but reflective of broader systemic issues in digital culture. The virtual world, which should be a realm of limitless possibilities and identities, seemed to be replicating and even amplifying the biases and inequalities of the real world.

This stark revelation served as both a challenge and a catalyst. It spurred me to delve deeper into the intersection of digital art and social commentary. My art evolved into a medium for interrogating and confronting these deep-rooted biases. By utilising the very mediums that perpetuated these issues my work aims to not only highlight the problems but also to envision alternatives. My goal is to uncover and critique the embedded prejudices within these digital spaces – It’s a journey of continuously pushing the boundaries of digital art and virtual worlds.

Matteo Bittanti: Works like Blood Paintings and 99 Problems [WASTED]resonate with groundbreaking performance art that spotlights violence against women, from Marina Abramović to Yoko Ono. Through interactive interventions, you also reveal problematic societal assumptions in ways reminiscent of seminal participatory artists pioneering that critical approach. Considering precedents like Abramović’s bodily endurance pieces or Ono’s instructional art prompting critique, which feminist performance artists have inspired your conceptual ethos or methods? Alternatively, is your body of gaming work intended as a form of avant-garde, activist art separate from lineages of traditional performance or participation art? I’m interested in your perspective on building on or departing from feminist art history – across disciplines and mediums – to advance piercing contemporary commentary on gender-based aggression and harm in both virtual and real spaces.

Georgie Roxby Smith: The punk attitudes of my artist fore-mothers – like Marina Abramović, Yoko and Tracey Emin – where there is a play between vulnerability and strength (with a f--- you confidence) was definitely a major inspiration behind my artistic practice. Abramović’s approach in particular represents a powerful exploration of the body’s endurance against external adversities. These performances were not just feats of physical endurance but also profound statements on vulnerability, strength, and the human condition.

In works like The Fall Girl and 99 Problems [WASTED], I draw from Abramović’s ethos but within the digital and virtual realms. While Abramović used her physical body as a canvas to explore violence and endurance, my work shifts this exploration to the digital body. The digital body, in some ways, is invulnerable compared to the physical body – it can endure extreme conditions without physical harm. However, the psyche of the player behind the keyboard is exposed to vulnerability, experiencing the psychological and emotional impacts of these virtual experiences.

This contrast between the invulnerability of the digital body and the vulnerability of the human psyche behind it forms a critical aspect of my work. It marks a shift from traditional performance art into the realm of digital and gaming art so in that way is avant-garde.

So yes, I build upon the rich legacy of feminist art history but while charting new territory. By engaging with digital mediums, my art not only pays homage to the critical approaches of artists like Abramović but also addresses contemporary issues in a digitised society, contributing to the ongoing discourse on gender, violence, and representation across various disciplines and mediums.

Matteo Bittanti: A unique aspect of your Blood Paintings series is the three distinct elements that comprise each piece – the in-studio artist video, the selfie with the artwork, and the digital/physical print hybrid. Can you talk about your decision to present the works in this multimedia format? How do you see the separate components interacting with and informing one another? And what do you hope the juxtaposition of the cold digital space with the organic performance and tactile art print conveys to those experiencing the paintings? Overall, what commentary might this innovative structure provide on topics like embodiment, reality, and the relationship between digital and physical artistic processes or outputs?

Georgie Roxby Smith: In my larger scale installations and earlier works like Reality Bytes, I was primarily exploring how to push mixed reality works to their extremes, effectively trying to dismantle the “fourth wall of the theatre” in mixed reality installations and performances. Blood Paintings represents a return to this concept but on a smaller scale, combining in-game performance, machinima, and the IRL print/digital painting. This series juxtaposes the violent creation process with the innocence and ego of the in-game selfie and the emerging ‘beauty’ of the abstract painting. The work also comments on the new nature of making, the new studio that digital artists work in that is often unseen by curators or audience – here exposed in a truly violent nature.

The unique structure of this series offers commentary on embodiment and reality in the digital age. It examines the relationship between the virtual and the physical, highlighting the distinct yet interconnected nature of these realms. The series questions traditional artistic processes, showcasing how digital processes can both emulate and diverge from physical art forms. By intertwining these elements, I aim to provoke thought about the evolving nature of art, identity, and expression in a world where digital and physical realities are increasingly merged.

Matteo Bittanti: The Blood Paintings series utilizes the disturbingly repetitive violence of GTA V gameplay as a genesis for abstract art, almost ritualizing virtual carnage into a meditative process. The pedestrian hit-and-runs conducted in-game mirror the rampant dangers of reckless driving cultures worldwide. For example, in Milan, Italy, where I spend several months per year, aggression and road rage are a daily occurrence. The Milanese drivers, perpetually distracted by their smartphones and completely indifferent to cyclists and pedestrians, are in aggro mode by default. So, beyond commentary on gaming itself, do you aim to spotlight how these virtual spaces might amplify or even enable real-world car toxicity? Overall, by interplaying such unsettling yet potent violence with art, what statements do you ultimately hope to make about aggression rooted in our systems and spaces, technology and society, both on and offline?

Georgie Roxby Smith: I live in the inner city as a cyclist and pedestrian (which may have subconsciously informed these works!) Particularly since our long lockdown in my hometown of Melbourne we are seeing increased aggression on the roads, I personally feel these games can desensitize users to IRL violence – and the performative in-game making was innately and deliberately shocking. My practice can be seen as a digital mirror to real life identity, sometimes warped, always amplified but it was an uncomfortable series to make.

I hope these works prompt discussions around society’s understanding and tolerance of aggression, both online and offline.

Matteo Bittanti: In Just Breathe, you technologically “rehumanize” your typically constrained GTA V avatar by simulating organic functions like breath with AI — an unsettling yet poetic personification. Does breathing life into virtual characters reveal surprising relationships between digital existence and physical vulnerability? Overall, what does this unusual augmentation of a gaming avatar indicate about consciousness, freedom, and the blurring boundaries between virtual and “real” embodiment in an age of advanced simulation?

Georgie Roxby Smith: In Just Breathe, the integration of AI-induced breathing into my avatar is not only about bridging the virtual and the real but also delves into themes of entrapment and perceived escape. This duality reflects the complex relationship we have with digital environments and our own identities within these spaces.

The concept of entrapment in the digital realm is multifaceted. On one level, the avatar is confined by the game’s mechanics and narrative structure, unable to transcend its programmed limitations. By introducing a fundamental human function – breathing – into this constrained entity, I aim to highlight the paradox of the digital avatar: it exists in a world of seemingly endless potential, but is trapped within predefined boundaries. This mirrors our own experiences in digital spaces, where we often feel a sense of freedom and escape but are simultaneously bound by the limitations of these platforms, whether through social constructs, algorithmic controls, or the very nature of digital interaction.

On the other hand, the act of breathing can be seen as a form of escape or transcendence. It symbolises a breaking free from the constraints of the digital avatar’s original programming, suggesting a new level of autonomy and existence. This infusion of a life-like characteristic challenges the notion of what digital entities can be and do, hinting at a future where the lines between human and avatar, real and virtual, are not just blurred but potentially irrelevant.

The work encourages viewers to consider how our digital and physical identities intersect and diverge, and how technology both confines and liberates us.

Matteo Bittanti: In 99 Problems [WASTED], your female protagonist recursively enacts her own virtual suicide amidst passive GTAV characters, crying out against misogynistic gaming worlds. This confronting, cyclical performance seems a precursor to the themes of your later Blood Paintings series. What existential commentary were you looking to make in 99 Problems [WASTED] about the cultural complacency and expectation of violence against women in video games? How are audiences meant to break from passive viewership by witnessing the endless destruction of your female playable character across repetitive deaths devoid of repercussion?

Georgie Roxby Smith: In 99 Problems [WASTED], my aim was to critique the cultural complacency and normalised expectation of violence against women in video games. This confronting and cyclical performance not only underscores the repetitive and normalised violence against women in these digital spaces, but also questions the broader societal attitudes that allow and sometimes even promote such depictions.

The existential commentary in 99 Problems [WASTED] revolves around the desensitisation of this violence, both in virtual and real worlds, emphasising how this violence is frequently overlooked, trivialised, or even glamorised within the context of gaming, reflecting a disturbing tolerance and complacency in wider culture. By presenting this violence in a repetitive, almost ritualistic manner, the work amplifies its impact, forcing viewers to confront the unsettling normalisation of such acts.

The endless destruction of the female character, occurring without any repercussion, is intended to reflect a mirror to the audience. It aims to jolt viewers out of passive consumption and into a more active, critical engagement with the content they witness.

The audience is challenged to reflect on their role as passive viewers or active participants in these narratives. Witnessing the continuous loop of violence I hope prompts viewers to question their own desensitisation to such content and to consider the broader implications of such portrayals in media.

Matteo Bittanti: In a sense, 99 Problems [WASTED] lays the conceptual groundwork to probe critical questions on gaming’s trivialization of misogynistic harm, questions further provoked by the structured “ritual killings” of your Blood Paintings. But while the action holds elements of protest and empowerment, the ultimate message of 99 Problems [WASTED] seems to be one of hopeless entrapment in an endlessly punishing cycle. Am I off track? How does this piece act as a metaphor for the dualistic relationship many feel towards the highs, lows, freedoms, and constraints experienced in virtual spaces or game worlds?

Georgie Roxby Smith: Absolutely, I feel like entrapment has been a constant theme in my work, whether it be how we are trapped by a sense of social expectation as to how we represent ourselves online and how our perceived selves are represented online by “others” (gaming entities etc). The concept of entrapment reflects the experience of many individuals in digital environments, where the lines between empowerment and victimisation, freedom and constraint, are often blurred. In virtual spaces, players can experience a sense of control and liberation, yet this is juxtaposed against the limitations and narratives imposed by the game’s/virtual worlds design and cultural norms.

Matteo Bittanti: Both Blood Paintings and 99 Problems [WASTED] spotlight and subvert violence against female characters in gaming spaces. Likewise, Fair Game [Run Like A Girl] explores destructive GTA V interactions but from an aggressor’s perspective, relentlessly targeting female NPCs. What compelled you to perpetuate these problematic yet revealing animations ad absurdum? Having established commentary on gaming misogyny through past works, how does obsessively “hunting” these stereotyped bots further your artistic interrogation into virtual gender dynamics and assumptions? Does forcing the medium’s disturbing tendencies to their extremes reveal underlying cultural biases that titles like GTA reflect and validate? Ultimately, do the sadistic pleasures promised by such games guarantee a terminal end for marginalized or objectified characters, and if so, how can that provoked realization inspire change in your view?

Georgie Roxby Smith: In these works I deliberately spotlight and subvert violence against female characters in gaming spaces. The choice to perpetuate these acts ad absurdum is a critical tool used to highlight and interrogate the normalised misogyny within these virtual environments. By exaggerating and repetitively showcasing these acts of violence, I aim to make the audience acutely aware of the problematic yet often overlooked or accepted aspects of gaming culture.

Fair Game [Run Like A Girl], in particular, adopts the role of the aggressor in GTA V, targeting female non-player characters (NPCs). This shift in perspective is crucial in my artistic exploration of virtual gender dynamics. It’s not just about highlighting the victimisation of female characters but also about examining the role of the player, the one who wields control and power in these digital spaces. By “hunting” these stereotyped bots, I aim to expose and critique the underlying assumptions and biases ingrained in such games.

This obsessive focus on the virtual violence against female characters serves to magnify and question the cultural biases and stereotypes that games can reflect and validate. It’s about pushing these disturbing tendencies to their extremes to lay bare the often unacknowledged misogyny and objectification prevalent in gaming culture. These exaggerated depictions force the audience to confront the uncomfortable reality of these biases and their implications in both virtual and real worlds.

By exposing and critiquing these aspects through my work, I aim to provoke a realisation and inspire change. It's about challenging the audience to reflect on their own interactions with these games and the broader societal attitudes they represent. Through this realisation, I hope to encourage a critical dialogue and contribute to a cultural shift that challenges these misogynistic norms, both in gaming and in society at large.

Matteo Bittanti: Many of your pieces powerfully interrogate issues of gender-based violence and embodiment across physical and digital realms. Yet some works like your AI portraiture experiments take a very different creative direction – leveraging emerging technologies in service of identity, representation and digitized consciousness. How do you see technological tools like AI, creative coding, and biometrics expanding the boundaries and capabilities of avant-garde digital art today in totally new ways? Your background across fine arts and computer science seems crucial here. In what directions do you hope to push your own interdisciplinary practice through continually engaging with and pioneering new media forms and methodologies? Could the infusion of complex machine learning ever aid humanistic goals around understanding intersectional identities or hidden systemic biases by rendering them visible? I’m curious about your outlook on AI’s double-edged sword in both perpetuating and revealing urgent societal issues.

Georgie Roxby Smith: The themes of identity were a foundation of my thesis Art 2.0: identity, role play and performance in virtual worlds and have underlined all of my subsequent works, although AI technology was a definite catalyst to re-explore these themes at their core within new emerging technologies.

I am fascinated by AI as a tool for exploring identity, allowing for a deeper examination of digitised consciousness and representation. And of course aligns with my interdisciplinary practice, where I continuously engage with new media forms, pushing the boundaries of digital expression. AI’s potential to reveal underlying cultural biases and intersectional identities is significant – while relatively new, I think AI is a tool to be critically and carefully embraced by digital artists. Right now, I am seeing many artists explore the ‘uncanny’ in their use of AI and while these works are visually captivating and of the time, they are most definitely only the beginnings of where this technology will take us.

Blood Paintings

digital video, color, sound, 11’ 06”, 2024, Australia

Created by Georgie Roxby Smith, 2024

Courtesy ofGeorgie Roxby Smith. 2024

Made with Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013)