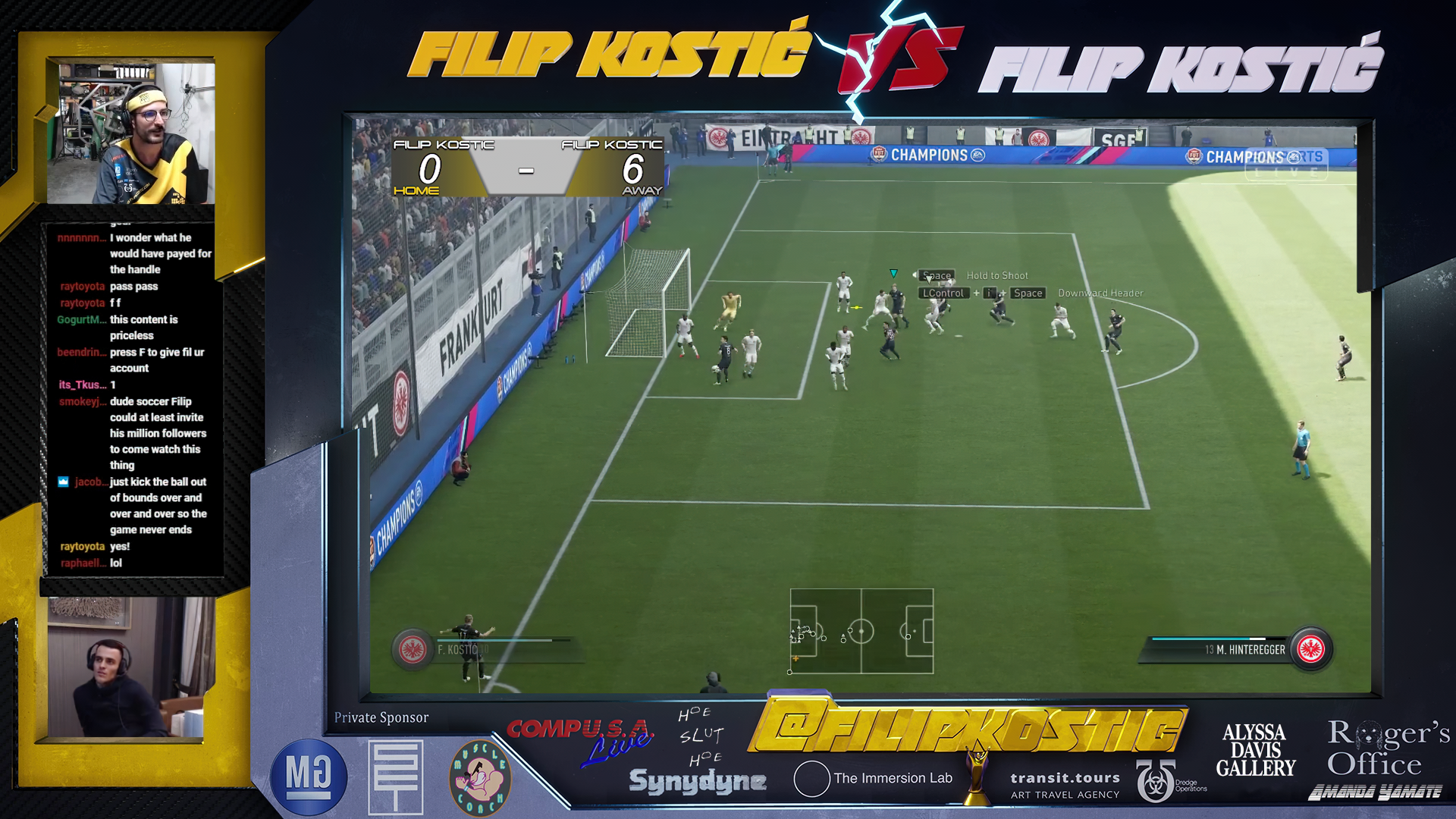

Filip Kostic VS Filip Kostic

digital video, color, sound (1920 x 1080), color, sound, 16’ 28”, 2019, Serbia/United States

Created by Filip Kostic

Online premiere (new edit)

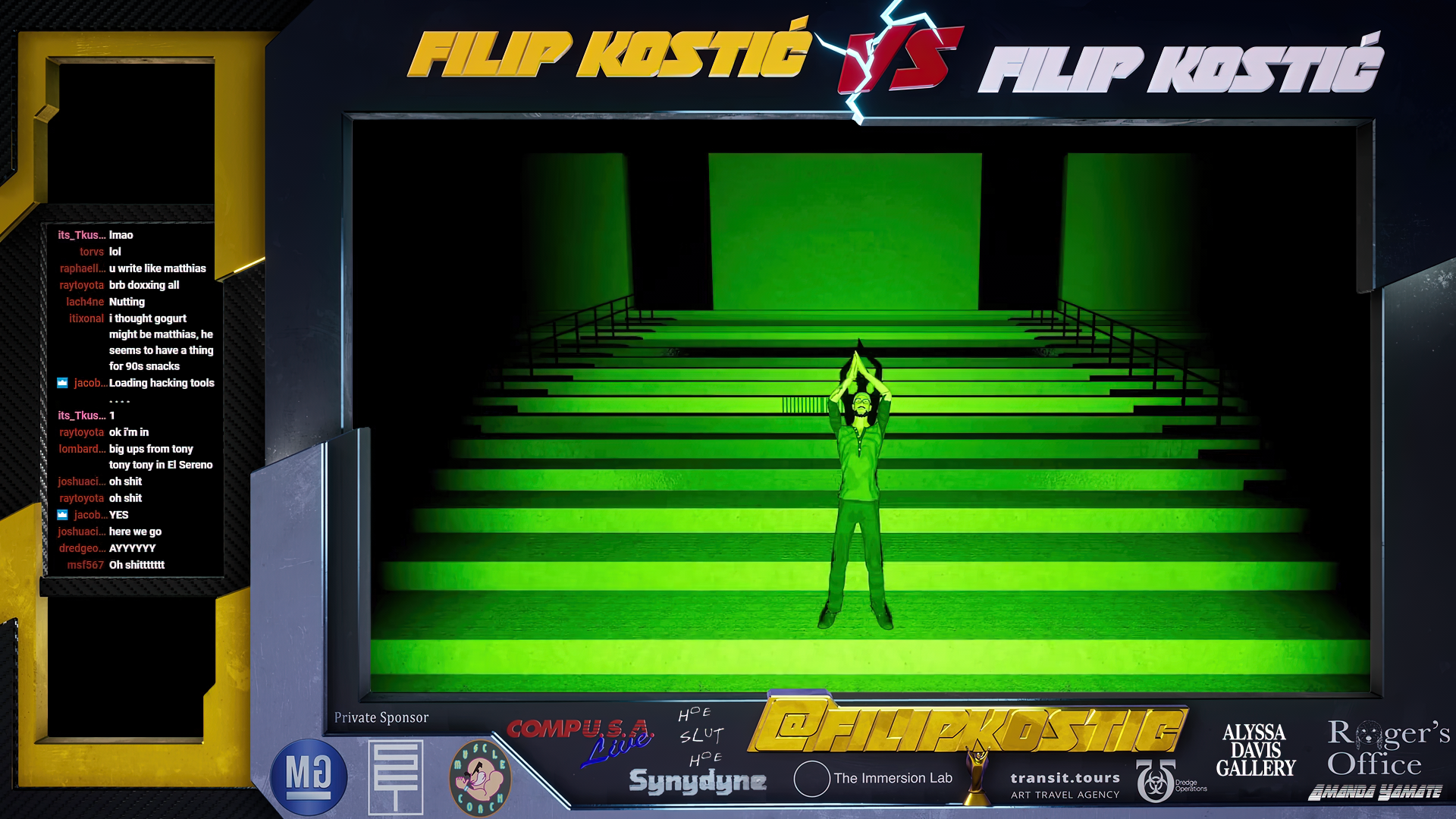

Filip Kostic VS Filip Kostic (2019) is a performative artwork by artist Filip Kostic, staged as a live Twitch stream. In the piece, Kostic plays a match of FIFA soccer against Serbian athlete Filip Kostic, who shares his name and nationality. The prize at stake is the @filipkostic Instagram handle. For years, Kostic’s online identity was conflated with that of the athlete due to sharing a name and IMDb page. After being contacted by Kostic’s PR team to purchase his Instagram handle, the artist instead proposed this competitive FIFA face-off to settle the score. Presented as an eSports event, the Twitch stream featured a custom layout with sponsors and a halftime show performance. It is now presented on VRAL in a novel edit.

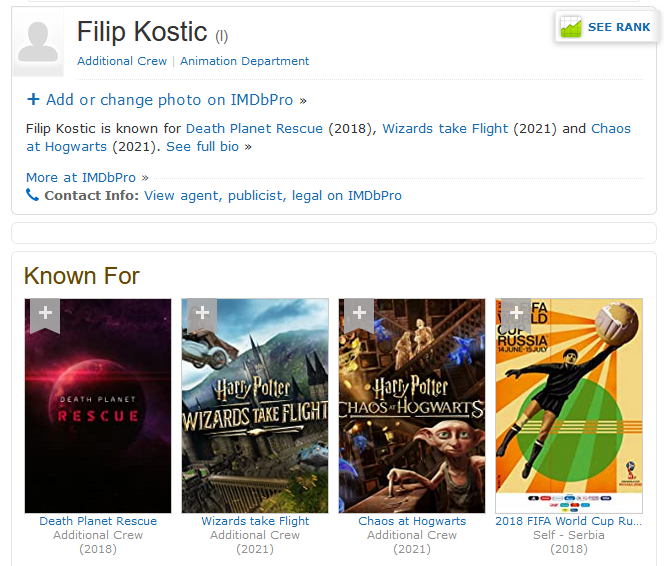

Filip Kostic is an interdisciplinary artist working across video, performance, sculpture, and interactive media. His video and new media works have been shown internationally at venues including Ars Electronica Festival, Ujazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art, and SPRING/BREAK Art Show. He has exhibited sculpture and installation works at galleries in the US and Europe. Kostic holds an MFA from Bard College and a BFA from ArtCenter College of Design, where he currently teaches in the Interaction Design and Fine Art departments. He has previously taught at Otis College of Art & Design and Cal State Northridge. From 2018-2021, he worked as a technical artist and game designer at WEVR on VR experiences for the Harry Potter franchise. Through his multimedia practice, Kostic invites viewers to examine and challenge assumptions about identity, reality, and the role of technology in shaping human experience. His work aims to collapse boundaries between the real and the simulated. Originally from Belgrade, Serbia, he is currently based in Los Angeles.

Matteo Bittanti: You’ve worked extensively in the gaming industry as both an artist and designer and, perhaps unsurprisingly, you often incorporate game aesthetics and concepts into your artwork. Running at Frame Rate, Booty Bay Open Studios, Filip Kostic VS Filip Kostic, and Open Loop engage directly with gaming tech, the “hard core” community of players, and online culture. How do you navigate your relationship with the video game medium across your roles as artist, designer, and player? In what ways does your insider experience in the industry lend a critical perspective when exploring themes of simulation, representation, and identity in your art?

Filip Kostic: One of the most useful ways to be critical of something is to be inside of it and to love it dearly. It’s then that the criticality is foundationally rooted in the desire to see that thing be better. I feel this way about video games and the culture surrounding them as I have grown up immersed in them and as a kid, I dreamt of making them one day. They have defined a large part of me as an individual and I am incredibly reverent to them, even in my projects that are largely critical of them. I did a project recently titled Fortnite: 007 Merciful Angel where I remade a single player version of Fortnite because I was interested in the nature of cultural collapse that the game represents. In the most crude way possible, Fortnite smashes together different franchises irrespective of their cultural meaning or aesthetic goals, and more or less convinces their audience that this is totally normal.

This is symptomatic of a very specific moment in the neoliberal plot arc that Mark Fisher discussed in his writings, in which the new is conjured through the remixing resampling of the old. In the case of Fortnite though, it is the sampling and mixing together of franchises worth billions of dollars rather than music from underground scenes. I am incredibly reverent and simultaneously suspicious of this cultural object, and Epic Games for that matter, and this is where this project and my pressure towards the subject comes from.

After working on a big production, I realized that there is very little critical inquiry in that industry – in fact it is much more productive to not ask “Why are we doing this?” because there is often not enough time or money to execute without any hitches. I ended up thinking a lot about this in my Bed PC project as I was responding to a role I had at work to optimize the game, so I decided to apply the same logic to my life by optimizing my home full circle in order to be a more optimum worker.

A lot of my work from the last couple of years comes out of a joining together of something that I am interested in at the moment (that may or may not have anything to do with gaming), and my professional work.

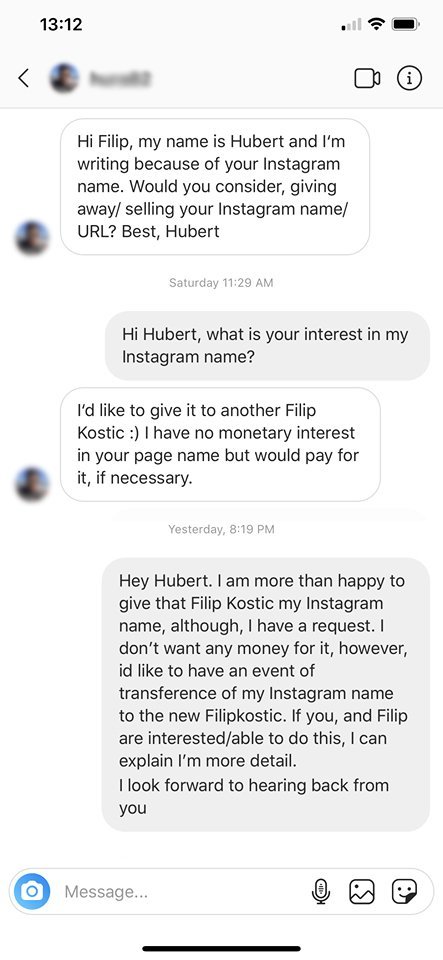

Matteo Bittanti: The somehow absurd premise of Filip Kostic VS Filip Kostic highlights questions of identity, fame, social capital, and authorship within the social media age. Engaging in a competition with your double in front of a live internet audience, you playfully explore notions of performance. Additionally, the staged broadcast introduced a “meta layer” questioning ideas of celebrity and personal branding. How did you go about coordinating and planning this event after refusing the original transaction, i.e. the sale of your instagram account? Can you discuss some of the logistics, the so-called behind the scenes?

Filip Kostic: The logistics to me felt so important for the work and I’ve been trying to figure out ways to make them more central in the project without just having representations of them in the form of print outs or something like that.

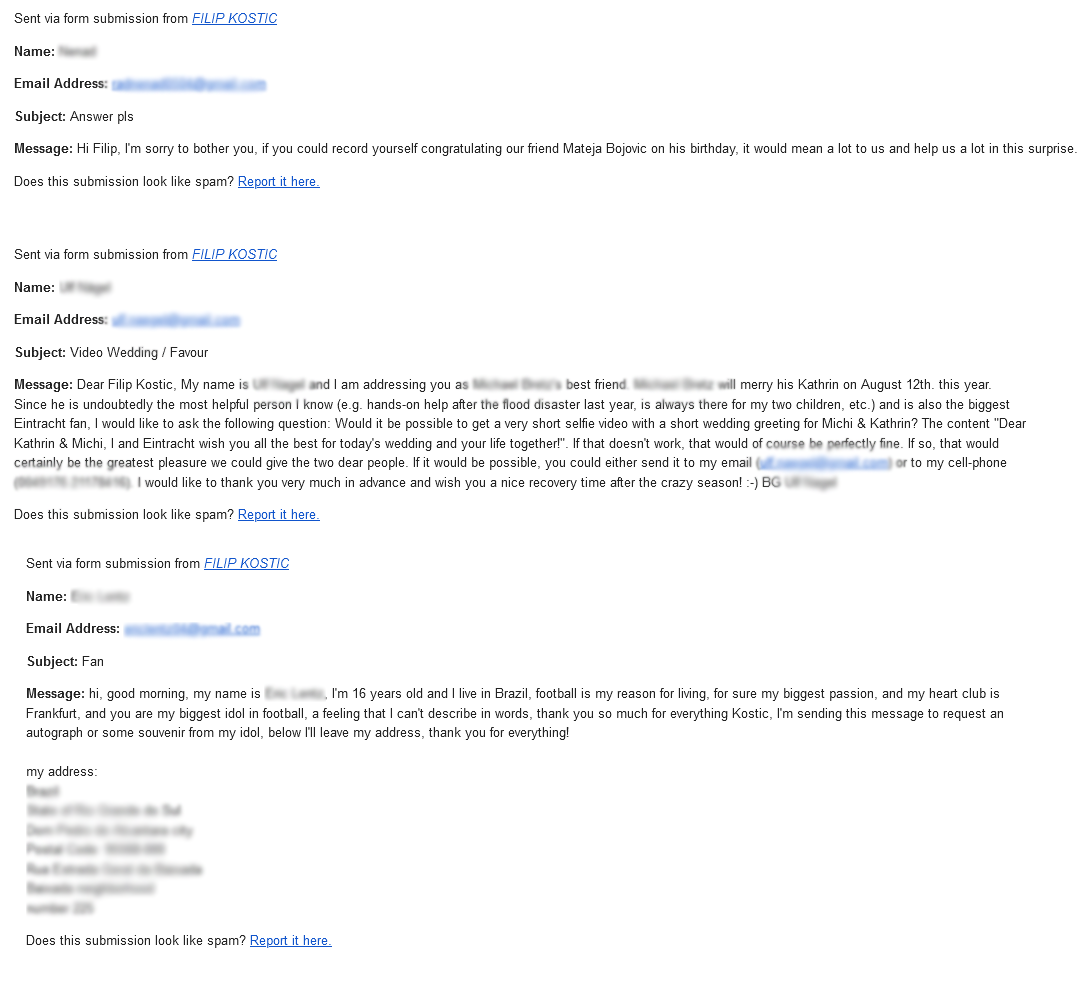

The actual exchange of handles from first contact to the final handover was strange and specific and I don’t know that I’ll ever have an opportunity to do something like that again, unfortunately. I was contacted by a random instagram account one summer by someone asking to purchase my account for a client. Instead of offering it for sale, I suggested we compete for it in a FIFA match – I called it an “event of transference.” I was then linked to Filip’s manager via whatsapp, whom I managed to convince that it is in Filip’s best interest to have a presence on Twitch, which to me was a part of the logistical sell of the project; I had to make the people who tell him what he should and shouldn’t do like this idea. In the beginning they were so into it that they were going to contact German news outlets and do a whole media campaign for it. I think at some point the team (Eintracht Frankfurt) got wind of it and talked some sense into Filip’s PR people, aka they told him the truth, which is: They don’t know me nor do they know what I can do, so he should tread lightly. He wasn’t in a contractual agreement yet, so he could have at that point just decided against it, but it was probably too enticing for him to have the handle. After that, the next point of contact outside of me sending them small snippets of the animations I was making was the actual match itself. Once the match concluded I was contacted by the manager to swap names which proved to be a bit of a problem. Instagram holds onto a username for 14 days after you change yours, so nobody can take it for 14 days. The issue was that his team was scared someone would take it before they were able to. This led them to get a direct instagram contact, which then reached out to me to ask me what name I wanted to change my IG to and they did it from their end. I chose “@immakingmovesinsilence.”(lol)

The last message I got from his manager was “you’re a cool guy” in response to me thanking them for participating in a strange event.

Matteo Bittanti: Blending performance art with a playful, extremely online approach and kaufmanesque vibes, Filip Kostic VS Filip Kostic probes the notion of online identity in an age of overwhelming misinformation, constant confusion, neoliberal prerogatives. What was it like to compete against your virtual doppelgänger? How did it feel to play against Filip Kostic who, like many soccer players, is not “just” an athlete, but a brand, a marketing juggernaut, a sandwich-man who can kick a ball?

Filip Kostic: I was thinking a lot about Filip’s relationship to labor vis-a-vis his body, his image, and the scale at which he is remunerated for said labor compared to my own relationship to these subjects. As a football star you are not immune to the precarity of being a replaceable laborer; when Filip’s body fails to perform as an athlete at the level deemed by the sport/the club owners as “high level,” he will be replaced by a younger and more capable football player. It is in his best interest to create this multi layer income scheme that we call athletes today. Obviously, when this happens he will likely be fine as his contracts with these teams are in the millions, so I speak mostly structurally when I am thinking about this – as in, how does capitalism structurally instantiate between all laborers? There is, in some ways, a 1:1 relationship between Filip’s labor as an athlete and mine as a person working within the “creative field,” in both the precarity of the jobs, as well as our reliance on the thing that the match is actually wagering: A clear brand image and identity online.

Both our jobs are valuable culturally rather than pragmatically – meaning that we don’t do infrastructural work like building or maintaining roads, but I like to think that what we do does shift culture, for better or for worse. This specifically positions both of us where we are asked to perform the brand of ‘Filip Kostic’ in ways that someone who does build roads might not have to. Again, the clear difference in compensation between someone like Filip and me should not be downplayed, and in ways it is this gap that necessitates both of our behaviors: Filip successfully transcending the “athlete as person who plays football” into “athlete as capital generating asset” is the model through which all creative labor validates its behavior, specifically that of the individual artist. The bizarre practice of “artist account vs personal account,” the cloutbombing, and the aesthetic presentation of self and one’s work is all a ‘necessary’ professionalization of something that probably never should have been a job in the first place.

In short, it was really fun to play against him in this match. I kept thinking about these ideas while also performing them, and him performing them back to me without being asked to was really exciting and strange.

Matteo Bittanti: In light of your observations concerning Filip Kostic, the athlete-as-celebrity, and taking into account the intricate intersections of labor, personal branding, and identity in both sports and the creative sectors — not to mention the precarity, the need for diversifying your sources of income, the cultural capital generated by your respective practices - how do you interpret the evolving role of the artist as both celebrity and brand within a neoliberal context? Are there ethical or philosophical considerations that arise from this transformation of an artist from primarily a creator of works to a “capital-generating asset”? In other words, how do you frame or “position” Filip Kostic, the “interdisciplinary artist working across video, performance, sculpture, and interactive media”? How do relate to your “brand identity” and “brand image”? There’s an interesting work by a collective called The Cool Couple titled Emozioni Mondiali (2018-ongoing) where players in Pro Evolution Soccer are replaced by avatars of renowned artists to explore the concept of competition within the art world which is somehow pertinent to this conversation. And finally, how do you view the choice of EA’s FIFA as a platform for this peculiar “match”? Given FIFA’s position as a mainstream video game that encapsulates hyper-capitalist elements like loot boxes, gamblification elements and multi-layered income schemes for the company — a central theme inDaniel James Joseph’s research— do you think it serves as an appropriate arena for critiquing or reflecting upon the competitive aspects of both art and sports?

Filip Kostic: After I gave my account name to Filip, I did an ‘identity crisis’ performance (if you can call it that) on instagram where I changed my handle and also the content I posted every week or so. My interest in this public sketchbook of a project was to put into question that very thing - what is my relationship to the artist as brand as company as hustlepreneur. One of those account handles was @man_on_the_line where I posted content only about the ‘protagonist’ from the old game Linerider (mostly because I was obsessed with the game at the time). I made a track/video essay that I posted to instagram called Clarity where I address my audience who was absolutely confused by what I was doing because I wasn’t explicit in my intentions while doing it, and also address some of these ideas we are talking about – like, how do I use instagram meaningfully if it privileges a specific use that I am not particularly interested in. Funnily enough, the sole comment on the YouTube upload mistakenly identifies me as Filip Kostic, the professional football player.

Filip Kostic, YouTube comment.

The identity crisis project ended with Mark Fingerhut and I exchanging instagram accounts, and in his use of my account he plays out an intricate performance in which he kills me convincingly enough for me to get dozens of phone calls and texts asking if I am okay.

I am still figuring out my relationship to the artist-brand-company-individual-celebrity meta, and I think that my work is at times a contention with this – I tend to play out these characters that tease that out in a lot of my projects and more explicitly in the way I post.

As for FIFA as a platform: I’ll be totally honest, the impetus to use FIFA was that I knew he was in it as a character model and I needed that as a formal element in the project. I am certainly interested in the loot box gambling aspects of nearly every game that comes out now-a-days. Lately I’ve been obsessed with watching streamer Xqc both literally gamble on his livestreams on a slots website and gamble with Counter Strike Global Offensive loot boxes, on some streams going through millions of dollars (whether real or not is almost irrelevant) in hours. In a funny way, I think that these Xqc gamble streams, the PES project by The Cool Couple and its exploration of competition in the art world, and loot boxes are all representative of a symptom of the neoliberal plot arc point that we are in. Art with a capital “A” necessitates its relevance by, amongst other tactics, creating a false sense of competition between participants that is inherent to sports – I genuinely believe this to be true, but I also recognize that, as an artist, I am forced to exist within that until we are able to change it.

Matteo Bittanti: Can we discuss the original performance? If I understand correctly, the event was broadcast at Rogers Office in Los Angeles, Mery Gates in Brooklyn, New York) and Alyssa Davis Gallery in New York City. What kind of reactions did you get from people watching the live stream? How did the various audiences engage with this performance? How many people were there for Kostic the athlete and how many for Kostic the artist? Finally, can you discuss your own relationship with live streaming?

Filip Kostic: The ideal viewing of this performance was to mirror something like a Super Bowl Party, or getting together with friends to watch the Playoff game of whatever sport you all are into. I had a bunch of “sponsors,” or people/entities that were interested in being involved in the project and in return I provided advertising space. These three galleries offered to screen the match while it was happening at their spaces and I saw this as a sort of bridge between the typical art experience and that living room event.

I am pretty sure that the entirety of the audience was my audience, but there was no way to be sure. I think the stream peaked at 250 viewers or so, so there very well could have been Kostic fans in the audience. If the chat is any indication of how things went, then people really enjoyed themselves and the project. It was important to me that this performance worked well as a stream and as an artwork, so it needed to be entertaining.

I make works that exist in both the subcultural context of their referent and in the art context simultaneously, and it is important to me that the projects never use one as a crutch for the other – for instance, I don’t want to set out to make a live streamed project that is a ‘bad’ live stream, but it is okay because it is an artwork. I often think about the way that Claire Bishop talks about this relationship in her book Artificial Hells with regards to Activist Art projects from the ‘90s. These works tend to fail as being politically useful within their pursuits, and they fail as artworks within their proposed context, but they use each context as an excuse for the inability of the other.

For a long time, I hesitated to categorize my work as performance-based, largely due to my preconceived notions shaped by a narrow canon of performance art. These traditional forms did not align with the live-streaming projects that captivated my interest. However, my perspective shifted after engaging in conversations with fellow artists Mark Fingerhut, who performed in a half-time show, and Rae Kelly, both of whom were involved in a collaborative endeavor known as Comp USA Live.

I now consider my live-streamed performances to be part of a lineage that includes that innovative project. They both individually brought up the idea of “Desktop Theater” in our conversations, which is a literal bringing of people onto the desktop as characters and using the desktop itself as a character. I approach live streamed projects in a similar way because of how proximal live streaming and theater are to each other – the interface is your set, there are clear actors (like the streamer) and less clear actors like real time elements that you choose to include (chat, different interactables, etc), and the real time element is incredibly important in every layer of the production not withholding the performance itself.

Livestreaming is a confluence of a lot of my interests as an artist. It’s the main character syndrome in which the streamer is the main character, but so is every parasocial member of the chat. It is reality television in the way that Josh Harris’s We Live In Public project was reality TV in that it is either hinged on or is interesting because of the believability that these are in fact real regular people on screen, and they are much closer to us than other celebrities because they game from their messy bedrooms.

Matteo Bittanti: Right. I always tell my Gen Z students to check outOndi Timoner’s excellent 2009 docon the proto-social media age. In your piece Running at Frame Rate, you focus on frame rate itself as a way to critique the pursuit of realism and ever-greater graphical fidelity in games and simulations. You position “running at frame rate” as an economic imperative rather than just a technical one, with demands now placed on higher frame rates. I’m interested in how this subverts the clichéd pseudo-binary of “real” vs “simulated” - it seems more concerned with critiquing a specific construct of realism in digital media, tied to economics and labor. Could you discuss more your intentions behind foregrounding the computer’s “experience” in this piece, and how this shifts the focus away from common debates about virtual vs physical realities? What drew you to frame rate specifically as an avenue for questioning the implications of graphical improvements and photorealism in games and tech?

Filip Kostic: I’ve felt for a while that the distinction between the physical and the digital is a pretty goofy one, and I used to try to drive home how convoluted the intertwined reality of these ideas are today. This project definitely started with me thinking about how this distinction felt delusional, and its original iteration was much more focused on that. The work I ended up with feels much more nuanced, although it carries its original sentiment about the virtual vs physical debate with it still.

When I started working on Running at Framerate, I was just getting into the “optimization” phase of my job on the Harry Potter VR production. The process of optimizing in this project meant finding places in the game where we could downscale textures, reduce the amount of polygons in a model, refactor some logic to simplify it, or really anything we could do to get some frames back because ‘more frames per second means a better experience.’ In VR, bad framerate will actually make you sick, so there is a clear advantage to being at the hardwares specified framerate. Essentially, the thing needs to run smoothly so our movements in physical space are matched without hitch in virtual space in order for our inner ear to not get thrown off, which makes us sick – a real material consequence of bad optimization. This relationship between bodily function and framerate felt like a good place to start from.

I wanted to make a piece of software that would edge your hardware to the point of collapse and then back off. I wanted that to be an individual experience that anyone who downloaded it could have, regardless of their hardware, and that within that experience they would become closer to their computer. As the software runs it gradually ramps up the visuals on the screen until the computer running it begins to run at sub 1 frame per second, it remembers what caused that, and then adjusts to try to do more before reaching that again. As it works harder the hope is that the viewer begins to notice that the fans have kicked in and are trying to cool down the components of the computer while it works to display an image. The goal is to make apparent the physical processes happening in the hardware to do the thing that feels so seamless: show image on screen. I am pretty obsessed with how image is rendered to the screen in general, not just in gaming, and this project let me scratch that itch.

The project uses assets from a tech demo for Unreal Engine in 2018 in which they show off a new version of the engine and the new tools that come with it. The events tend to be hype fests for oftentimes undercooked tools that require audience buy-in to finish their development, a process that we are all incredibly familiar with within most products and services today. The focus of these demos, and video games in a sense, has been to more accurately represent the real world in a simulated environment. The companies making the hardware team up with the companies making the software in an effort to simultaneously reach this goal of “Realism” while creating a perfectly contained ecosystem of reliance between their consumer and them. I quote realism because it is a specific representation of the real without the material conditions that this real exists in, or a fantasy that still exists in a world that visually mimics our own, but omits its context. This isn’t the Realism of the 19th century that showed the conditions of contemporary society, this realism specifically wants you to not think about that. Running at Framerate takes that framing of the world, and quite literally world-building, and slows it down for a second.

Matteo Bittanti: In Open Loop, you create an AI character trapped in a repetitive loop, evoking ideas of determinism and free will. The character repetitively walks, dies, and respawns with no control over this cyclic process. You’ve mentioned this work draws aesthetically from video games and PC building culture as a means to explore philosophical debates around agency and determinism. I’m interested in hearing more about how you use the visual language of digital games and computers as an entry point into a critical deconstruction of these conceptual themes. What appealed to you about conveying the ideas of endless loops and constrained choices through a simulated character in a video game-inspired structure? The treadmill metaphor seems pertinent: walking, even running, without ever going anywhere. By personifying the AI and computer processes, you seem to give tangible form to abstract philosophical questions. Could you discuss your intentions behind this anthropomorphized approach?

Filip Kostic: I made this project in 2016, so probably right as AI stuff was about to take off but definitely before it became the cultural behemoth that it is today. At the time I was learning about designing NPCs in Unreal Engine using a system called behavior trees and became interested generally in the limits of these programmed behaviors. Performing the limits of these behavior trees are the things that are now, in 2023, becoming virality schemes for individuals doing live streams in which they behave like an NPC.

In my research for behavior trees and AI in game design I came across the concepts of open and closed loop systems, which became the titles of the works and the show title I did in 2017 at Roger’s Office. Simply put an open loop does not feed back into itself and a closed loop does – so within something like an NPC: a character that responds to its behavior loop and adjusts it according to external factors is an open one, and one that just behaves based on a set of parameters without feedback is a closed one (or at least this is what I ran with.) The theme of “loop” felt really important which was the impetus for the circular set up, and which dictated the entirety of the formal gestures of the sculpture. I wanted to literalize this notion that the thing that distinguishes sculpture from other art is that it is “the thing we walk around in order to understand” so I made something that literally forces its viewers to walk around it in order to follow the little character on screen.

I do struggle with the metaphor of AI and the human brain, because it’s a false equivocacy, so I definitely did not intend to make that direct connection in my attempts to anthropomorphize the behavior system. I was however thinking about themes of agency within systems, like capital, that frame and define our own behavior trees. That example of tiktokers going on lives doing NPC behavior is a really illustrative one in a funny way. They are performing the thing that I was researching for that project, but also, as artist and researcherJoshua Citarella said in a New Models podcast:

It seems like people are being instrumentalized by the algorithm itself. If you look at TikTok, your body is literally animated by the algorithm. It tells you how to move yourself and you end up dancing for this abstract formulation of capital and algorithmic recommendation.

Open Loop is concerned with this question of agency while also wanting to be light hearted. Ultimately, the character dies in some funny way or other in every scene, and is reborn again on the screen adjacent to it, until the gallerist turns the software and computer off. It is, as Unreal Engine calls it, an agent, and its agency is ultimately framed by the sculpture.

Matteo Bittanti: In past interviews you’ve reflected fondly on the early internet days compared to today’s platform era, seeing that period as more expansive and hopeful. As we continue to see the promises of web3, the “metaverse”, the blockchain and the likes, fall short in delivering any real innovation, where do you see opportunities for artists to shape the conversation about the internet’s future? With social media fatigued and imploding, combined with the failure of these PR tech fantasies, it feels we are at an inflection point. As someone interested in gaming and internet subcultures, what role do you think artists and creatives can play in pushing for a future web that recaptures some of that early potential? Are there ways we can challenge the current model of platform capitalism and reimagine digital spaces?

It is certainly an uphill battle to shape something like the internet, especially with the stranglehold that platforms have on it, but I do think the best thing to do as an artist is to continue to make things that you want to see and do so for the audience that you want to engage with. If there is anything we know for certain is that these things are cyclical and each one of these platforms, however big and important it may feel now, in 20 years they will likely feel as relevant as something like xanga does today. Keeping up with the treadmill of takes and content is exhausting and doesn’t yield much of anything – I know because I did it for the entirety of the pandemic.

Despite my criticism of the state of the internet and my nostalgic views of its past, I still think there are so many great little pockets of it that feel wonderful. There are many community hubs and people trying to make the internet feel better at various scales and rates of success. It is not at all incentivized by the platforms unless they have a way to capture its output, but people are doing it. Projects like Do Not Research do this in a formal way via discord and substack, and they have a cultural output that is relevant and exciting and would maybe not exist if it wasn’t for the web landscape we have today. Maybe the move is to make it difficult for platforms to harvest data etc, where you can, post incessantly and constantly in an effort to fill the servers with non-specific data, post meaningfully when you feel inspired, and have fun while it’s all so fragile and weird.

It’s a weird thing to try to imagine a different internet. It really is difficult – I do believe at the heart of web3 is a genuine effort to do something new and different, but we have all spent way too much time on the internet, invested too much of ourselves into it… the next thing needs to feel a lot better than the iterations presented and I am hopeful they will!

Matteo Bittanti: Your ongoing Personal Computers project explores the aesthetics and material culture of these devices in a way that feels both nostalgic yet ultra-contemporary. For example, in Couch Computer you transform a quintessential domestic furniture piece, the couch, into a functional computer with designated “good” and “bad” screens. This seems to comment on how networked technology has collapsed distinctions between public/private and labor/leisure spaces, especially in the context of remote work. Your process focuses on an examination of the blurring boundaries between work/play, domesticity/productivity through repurposing the imagery and objects of computing. How do you view the function and meaning of the “home” and “personal” computer” in relation to labor and identity?

Filip Kostic: At this point, after the covid work from home shift, the space between leisure and work hangs on by a thin thread that is entirely determined by an individual's ability to hold that boundary. This boundary is something that I struggle with, and Bed PC (the first in the Personal Computers project) came out of that struggle. I was working on the tail end of the Harry Potter production from my tiny bedroom where I would roll out of bed and into my computer chair in one motion, boot up my personal computer, log onto the VPN for work, do my day of work and then sign out of that VPN on the same computer, and open up the software from work that I just closed in order to work on my own work. The line was nonexistent, it was all the same thing – Slack has the function that I know is intentional where when you exit out of it it just closes the window but stays open in your toolbar, so I’d get messages from someone at work freaking out (and they knew I was at my computer because everyone was) and I’d feel an obligation to not just answer, but fix whatever was broken.

I made the Bed PC as a way to tease that relationship out, and moreover to figure out what my relationship to labor was at that moment. I thought about “optimization” as a practice and also as a joke — what if rather than traversing 5 feet of space to get to my computer every morning, I just stayed in bed? To me this computer seemed exciting, and in a child-like way it even seemed cool. It took living and working out of it for 6 months or so to realize that it was in fact dark, and my friends make fun of me for this all the time because they all understood it as dark from the very beginning.

The 24 Hour Stream performance from the Bed PC was another layer of the function of labor and the home being distorted into one another. I went live on twitch from the Bed PC for 24 hours, spending time doing everything I might do in a day at my computer, from work, to gaming, hanging out with friends, and browsing the internet – oftentimes multiples of these at once. Streaming as an occupation plays into the perceived proximity of streamer and viewer — it is in the streamer’s best interest to make the viewers feel as if they are mutuals, and there are many qualities inherent to the medium that reward this. The matter of fact quality of a streamer sitting in their chair situated in their living space, and that being present on screen while they play a game or talk to their chat is itself a simultaneous conflation of work and leisure with the actions of the labor being dictated by trends the platform prioritizes. A perfect example of all of these things coming together is someone like streamer KeshaEuw who plays League of Legends from his bedroom while screaming at the top of his lungs in reaction to things that happen in the game.

Labor and leisure have for a while been conflated in the cultural sense (love what you do and you’ll never work a day in your life), but the jump start of the physical and mental conflation of the two I attribute to the pandemic. I don’t think this is good in the long run, at least not if seen through the lens of neoliberal exploitation practices. While I do see and enjoy the benefits of remote work, there is something spooky about it – I feel as if we have invited the vampire to the doorstep inside the house.

Filip Kostic VS Filip Kostic

digital video, color, sound (1920 x 1080), color, sound, 16’ 28”, 2019, Serbia/United States

Created by Filip Kostic, 2019

Courtesy of Filip Kostic, 2023

Made with FIFA 20 (EA, 2020)