How to Fly

digital video, color, sound, 6’ 23”, 2020, United Kingdom

Created by David Blandy

How to Fly was originally presented by John Hansard Gallery in Southampton as part of the Digital Array programme supported by the Barker-Mill Foundation.

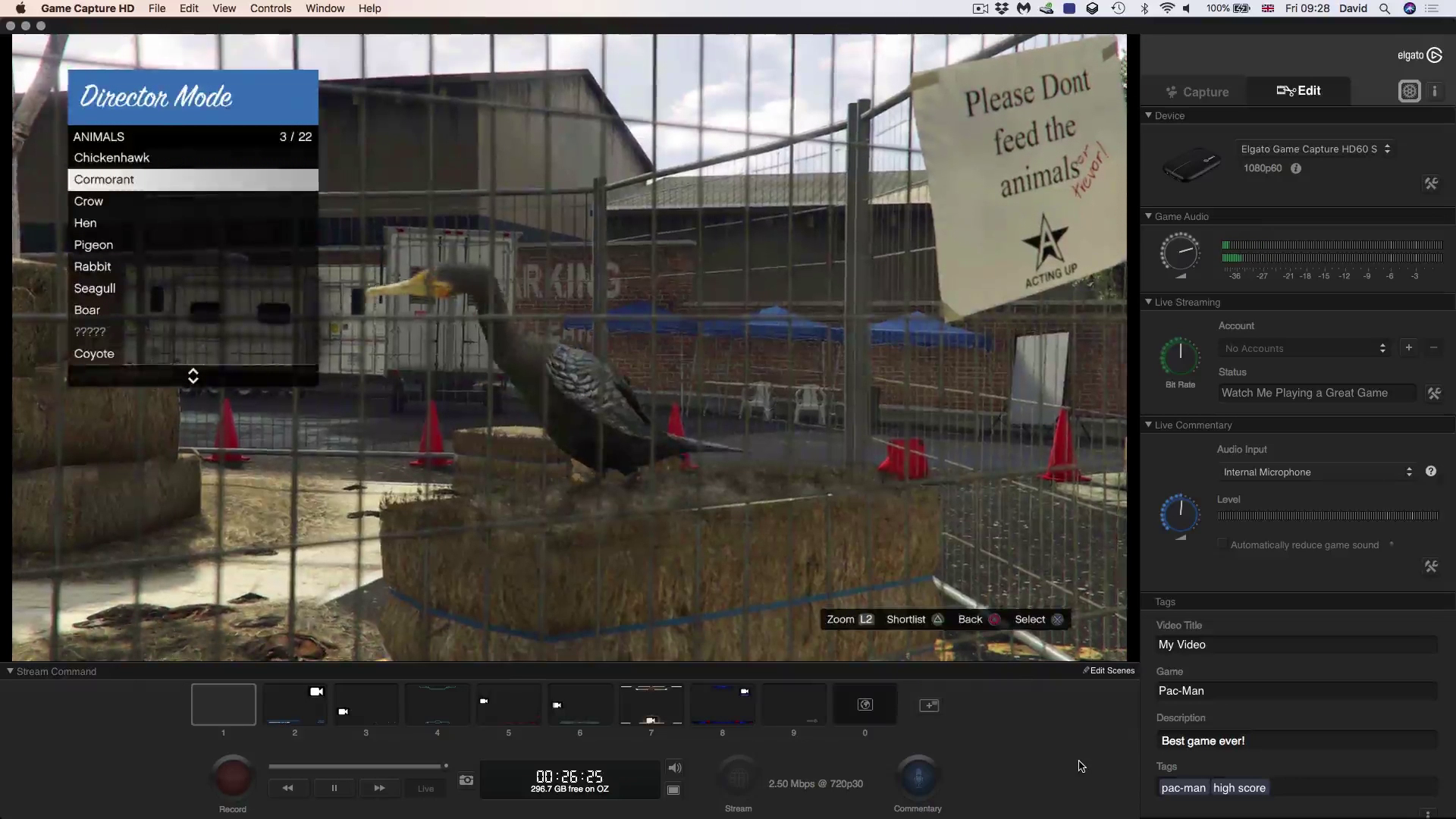

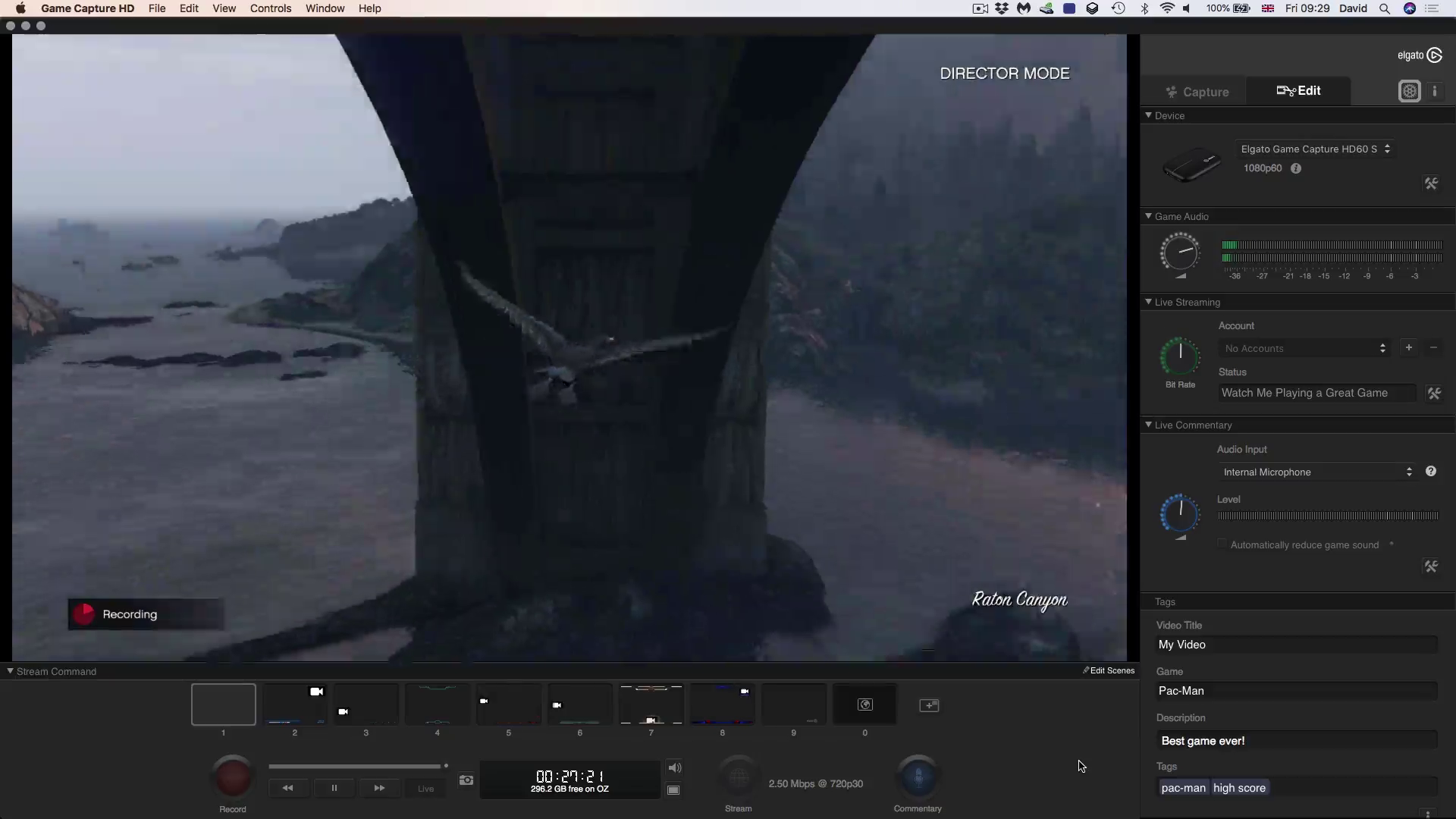

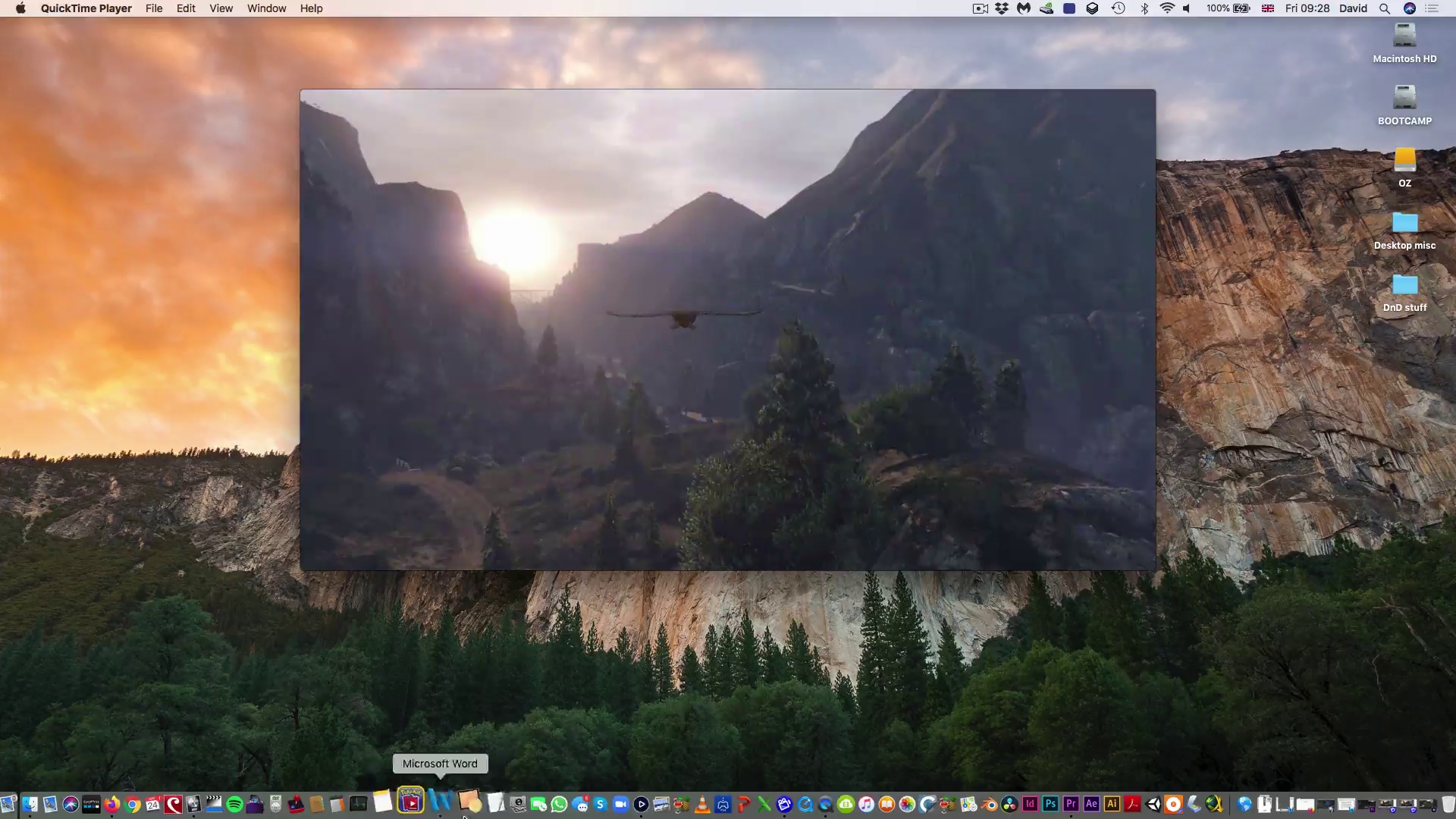

Originally commissioned by John Hansard Gallery in the United Kingdom and exhibited in May 2020, How to Fly uses the format of online video tutorials to explore ideas about life, nature, and technology. Created during the most intense months of the Covid-19 pandemic in Europe, How to Fly begins with the artist providing detailed information on how to make a short video about flying using the tools available on a computer, such as the Rockstar Editor, a popular video editor embedded in Grand Theft Auto V. “Hi guys. I’ve been thinking about making a film about flying,” the artist calmly tells the viewers in voiceover, before illustrating the process step by step. The entire procedure takes place on a computer screen: flying is enacted with the touch of a few strokes on the keyboard and experienced virtually. But How to Fly is not an ironic commentary on the state of the world. It is not earnest either. So, what is it, exactly? You decide.

David Blandy’s practice consists of in-depth investigations into the pop cultural forces that he experienced throughout his life, from hip hop and soul, to computer games and manga. His works slip between performance and video, reality and construct, using references sampled from the wide, disparate sources that construct and constantly reassemble his sense of self. David Blandy’s films are distributed through LUX. The artist is represented by Seventeen Gallery in London. Blandy’s work has been shown at numerous public institutions including Tate, London, UK; FACT, Liverpool, UK; BALTIC Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK; INIVA, London, UK; Künstlerhaus Stuttgart, Germany; Spike Island, Bristol, UK; Turner Contemporary, Margate, UK; Nouveau Musée National de Monaco, Monaco; Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art, Helsinki, Finland; Serpentine Gallery, London, UK; Witte de With, Rotterdam, Netherlands; Modern Art Oxford, UK; Kölnischer Kunstverein, Cologne, Germany; Site Gallery, Sheffield, UK and Focal Point Gallery, Southend-on-Sea, UK. Blandy lives and works in London.

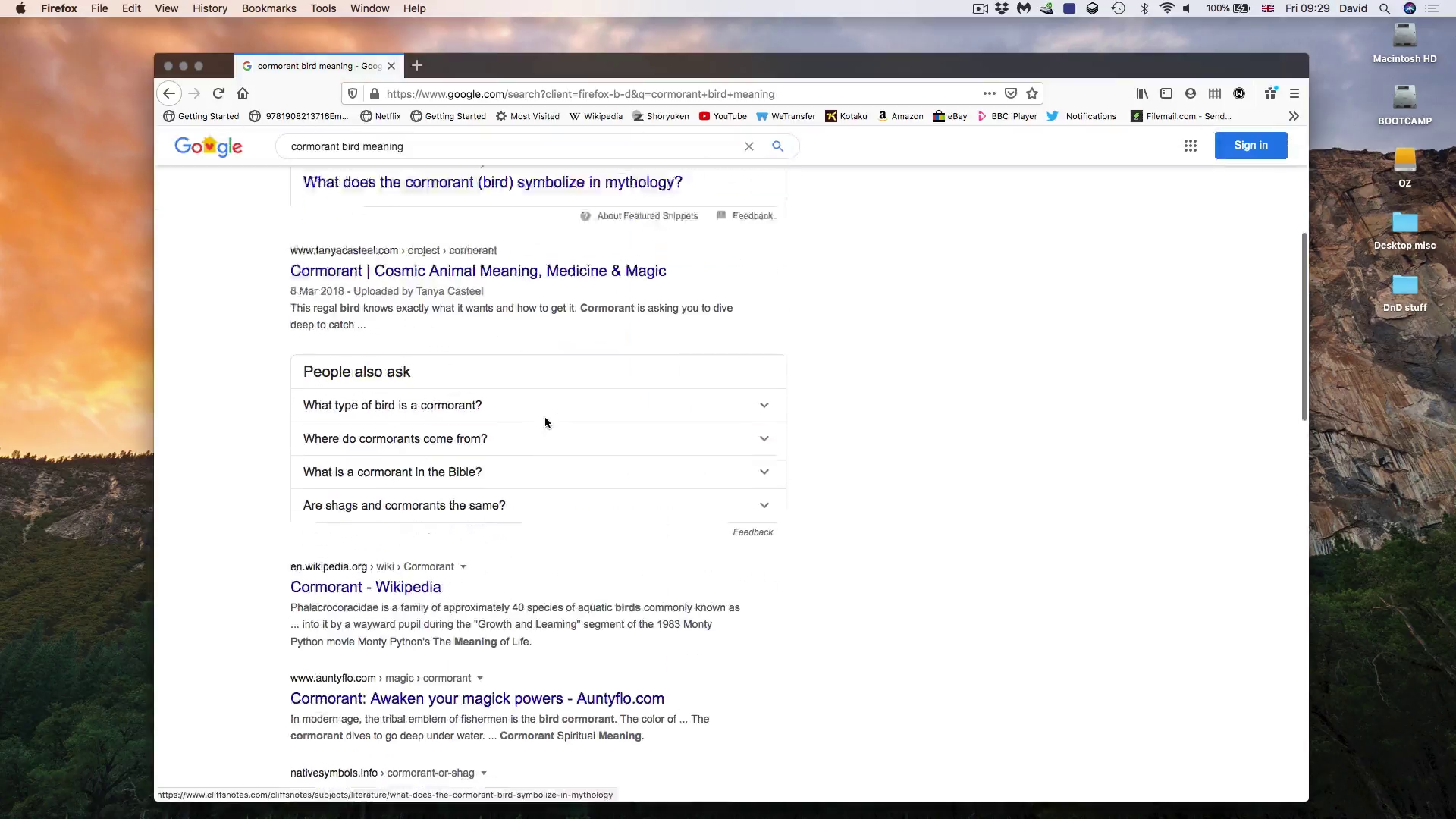

Matteo Bittanti: Film scholar Salomé Aguilera Skvirsky calls the tutorial an example of the process genre, a transmedial format that includes anything from step-by-step fabrication of objects, IKEA assembly guides, cooking videos, and factory tours. She argues that what these films really show is not content per se, but rather the aesthetic of labor, a sequence of acts that result in a desired outcome, the exhibition – not necessarily ostentation – of a craft, a set of skills. In How to Fly, we witness the creation of an entire world through the aid of several tools – from GTA V’s Rockstar Editor to Google, from Logic Pro to Adobe Premiere Pro. In short, is thus the “fly” considerably less relevant than the “how to”?

David Blandy: In How to Fly I was trying to find that balance between deconstruction and the sublime, to take apart what you’re watching while making you want to believe it anyway. As with many things, we know it is a fiction, but it’s hard not to give yourself over to the fiction anyway, for it affects you despite the breaking of the fourth wall. So I wanted the “fly” to be an equal counterpoint to “how to” and vice versa. The aesthetic of labour is there, but it’s only half-remembered once you enter into the flying section. This creates the tension in the work, forcing you to constantly choose whether to suspend your disbelief. Despite it all, I still believe in the emancipatory potential of video games, and indeed art, and I think the cormorant encapsulates all that.

Matteo Bittanti: How to Fly (2020) is part of an ongoing series of tutorials sui generis, which debuted in 2014 with How to make a short video about extinction and continued in 2016 with How to make a short video about ideas. The key concern of the first two works was epistemological: the increasing inability to distinguish between reality and simulation. However, How to Fly – and the same applies to its companion How to Life – seems more concerned about learning. In a sense, knowledge is cast as one possible way out of today's impasse. Tutorials are a staple of internet culture and especially video game culture but in this case what’s really being taught is the act of teaching itself. In a sense, How to Fly seems to reverse engineer the very act of creating the now pervasive How to video. By incorporating the “making of” rather than eliminating redundancies, mistakes, and incongruities, you are deconstructing the genre. You also highlight the underlying artifice in the act of storytelling. The first part of How to Fly, thus, feels self-referential and hypermediated, to use Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin’s term. The “final product”, on the other hand, showcases a tendency toward immediacy: by switching from the multiple windows display to full screen view, the viewer is invited to suspend her disbelief and fly like a cormorant in some kind of animated movie, “fully living in the moment” and experiencing “the digital sublime". And yet, knowing what came before – including the bird’s “sudden death” – abandoning ourselves to the fantasy and “believing the magic” is hard. Likewise, the message about stoicism and patience sound somehow hollow. Are you suggesting that bathos is the inevitable byproduct of digital culture? Has time finally come to denounce the deceit and to reject the technological promises of “empowerment”, “freedom”, and “agency”?

David Blandy: I think that there is a bathos in the digital, the nagging knowledge that all that you accomplish or learn is fundamentally illusory. But the experience is real. The relationships that you make through virtual platforms are real. The emotional impact of the space, such as when Aeris dies in Final Fantasy VII, is real. I think that there is a similar issue with any media form, but I think that the interactivity aligned with immersive worlds complicates our relationship to these spaces, attributing more agency to ourselves than is actually possible. Like in GTA V, it feels like anything is possible, I can walk anywhere I can see. But I can’t hop, I can’t itch my nose, and all these buildings are just textured boxes with no interiors. We know all this, but still want to believe.

Matteo Bittanti: In an age of perpetual economic crisis, constant uncertainty, and ongoing ecological catastrophe, has the tutorial become the defining cultural form, rather than the unboxing, as James Bridle suggests in his book New Dark Age? Is the How to genre a defense mechanism against the growing chaos of the world we inhabit, perhaps our last resort? “Follow these instructions and everything will be ok”... But what happens when the How to video becomes just another instrument of disinformation and manipulation? After all, its aesthetics are certainly conducive to induce a state of “passive indoctrination”: the soothing but authoritative voice, the direct address, the breaking of the fourth wall, the colloquial tone... In a sense, these videos are both cathartic and hypnotic…

David Blandy: Unboxing is pure fetishisation, a manifestation of the seductive nature of consumerism, somehow made more perfect by being witnessed through the screen, intangible, sealed off from you. Tutorials are about self-improvement, and range from simple tools (do this to get this effect) through to far more elaborate and intricate series, following the development of a meta in a trading card game, discussing techniques for running table-top roleplaying games, exposing a little-known glitch in a video game. The voice found in these spaces has an immediacy and intimacy, speaking to you personally in a way that TV never does. The home-made aesthetic helps this, the appearance that it is just one person and their computer, indulging a passion by relaying some information to you. In some ways the How To videos that I've made were a way to examine the function of voice in the online space, how the informality can draw you in to becoming receptive to a different kind of information with a change in vocal register. I suppose we all want there to be an answer out there, to feel like there’s someone who “knows”, and that compulsion has led to some very dark places.

Matteo Bittanti: “There’s lots to choose from, but I feel some kind of affinity with the cormorant”, you say while choosing your avatar from an apparently endless virtual bestiary. Like the cormorant, we are all “stuck in between spaces”: we’re simultaneously sheltering in place and travelling everywhere on our screens, alone together, always on, zooming in, zooming out. As the world literally implodes before our eyes, politicians and corporations deliver platitudes, if not outright lies, about our ongoing climate emergency. Institutional and corporate inertia creeps and dissenting voices, like Greta Thunberg’s or the fine folks behind Extinction Rebellion, are ridiculed and marginalized by the most powerful forces on Earth. When nature completely disappears and the desert of the real takes over, will non-human animals only survive in our digital fantasies, in our interactive postcards (“an undulating river, dirt road and a landscape of mountains and trees”)? In other words, is the digital cormorant akin to the robotic owl in Blade Runner, a simulacrum? Are “vast” “natural” “landscapes” possible only as a simulation?

David Blandy: I made this work very much in reaction to lockdown, of being confined, housebound, for most of the day, dreaming of landscapes and vistas. But yes, this is a very real risk that “nature” may only be accessible as an app, a robotic sheep slowly malfunctioning. Nature as simulacrum is nothing new, from the 18th century fantasy gardens of Europe to the intensely man-made landscape of farmed land or the cultivated wild spaces of national parks. As a species we seem to love the feeling and appearance of nature, while it is accessible and fundamentally safe. I went to the Grand Canyon once, and standing on the edge of it, feeling like I was looking at a fractal infinite distance of fissures and rock faces, it felt so distant. I wanted to get close to it but it just seemed to get further and further away. Nature is unknowable.I want to believe that we can turn things around, that we can somehow ease our pillaging of the planet and avert the imminent apocalypse. I’ve been thinking about it a lot through my table-top Role play game, The World After. The conclusions in the game are that humanity, per se, may not survive, but life will.

Matteo Bittanti: In your practice, you’ve constantly questioned the influence of culture in shaping someone’s worldview. Video games and anime create experiences that are perceived by individuals not simply as meaningful, but as crucial. And yet, rather than being spaces of alienation, perversity, and isolation, digital fantasies can also provide a context for new kinds of socialization, unexpected epiphanies or even intergenerational connections (I’m thinking about your Background project (2013), for instance, but also the Finding Fanon (2015-2017) series, which in its Gaiden (2016-2017) spin-off became a participatory, collective endeavour that you and Larry Achiampong created with the collaboration of paperless migrants and prisoners). What role did popular culture, and especially video games, play in your evolution as an artist? Is the role of the artist to highlight the tendency of entertainment, alongside politics, to normalize ideologies such as misogyny, racism, colonialism? How can art dispute the dominant narratives?

David Blandy: Video games were integral to my development as an artist. I grew up playing games, often far too obsessed with these virtual worlds. I suppose I’ve always been fascinated by systems, by how particular spaces work, and trying to find out how to break them. Trying to find that one move in a fighting game that has no reply, the item that guarantees victory in Final Fantasy VII (I spent a lot of time breeding Chocobos in order to get the best summon, Knights of the Round). My primary experience of video games was personal, or just with a few friends, so when I worked in a videogame shop for a couple of years in the centre of London, it was a revelation to discover the whole community around them, that there were hundreds of others even more intent on breaking these systems than I was. Absolute masters of fighting games and RPGs, who formed a tight community around these virtual spaces. Communities formed that crossed boundaries of race, religion, gender and sexuality. It was not without its problems and internal rivalries, blatant sexism and homophobia, but it seemed like there was a possibility there for a different model of society and connection, working together towards a common goal. It was this possibility that was part of Background, bringing my virtual life to my Dad and seeing what he made of it, and of the FF Gaiden series, creating a space for people to examine and talk about their world through the virtual landscape of GTA V.

I came around to thinking about games for my practice while I was thinking about the spaces that I inhabit, and I realised I’d been ignoring one space that was very important to my life but somehow felt outside of art. This was at art school in the late ‘90s, and most of the tutors were pretty skeptical that there was anything of value to be found in the videogame space. I suppose I was always aware of the absurdity of my fascinations, wanting to be a virtual kung fu master or adventurer, so ended up mocking myself, attempting Tekken moves in real life as a performance video, or imagining myself rendered in the Mario 64 universe. But I also saw the sublime in these ridiculous spaces, from the city of lights in Wipeout to Yoshimitsu’s Forest stage in Tekken 2.

Art can subvert forms, taking them apart and revealing the cogs that make them work. Using GTA V like we have has changed my relationship to that space. But it’s still primarily a horrific space, used for gunplay, pretty low-grade satire, and casual misogyny, as that’s what it was programmed to be. I think the role of the artist is to encourage analysis and self-awareness, to encourage reflection on our function in the systems that we live in, and try to show that that function is changeable, and that the system is too. So much is made to appear natural when it is anything but that.

Matteo Bittanti: As a corollary: video games provide escapism, a sense of mastery over the environment, illusory power, and a sense of agency. As the world becomes increasingly violent, hostile, and dangerous, are video games becoming a new kind of “gated playgrounds”, a place to enact fantasies of control and domination within often idyllic, pastoral spaces? Is escaping-into-a-screen-inside-your-own-room-and-fly-like-a-cormoran the only alternative to a dire reality? Is there something inherently wrong in experiencing the world only through a screen?

David Blandy: This form of escapism is a part of video-games experience, but video-game space is also a space to find and create new communities. Inside these virtual worlds, formed in the crucible of capital, new alliances can be made. Video games communities have been the foundation of incredibly reactionary forces, Gamergate and 4chan, but they have also forged alliances and friendships across cultures and nations. I would argue that the world is not becoming more violent, hostile and dangerous; it’s just that the violence of colonialism is now being enacted on the citizens of the old empires, not just their colonies. The violence is becoming more visible to the Global North, as national states have become colonised by corporations and the global elite.

Matteo Bittanti: Among other things, you’ve elevated Grand Theft Auto V’s director mode to an artform, transforming a game into a tool to create stories and situations. In your practice, the Rockstar Editor is not just a tool, but rather a tactic that you use to ask questions about incredibly complex situations, rather than providing easy answers. How do you think the practice of creating video art with video games will evolve as technology becomes more powerful and versatile in the next few years?

David Blandy: I think that artists will continue to make work that exploits the newest spaces created, using each new coat of digital veneer to examine digitality and the world around us. But I also think, as digital worlds become more ubiquitous, that there will be a growing cohort of gamer artists who both explore older videogame aesthetics and abandon the digital world altogether, seeking the real world communality found in table-top roleplay and LARPs. There is a large appetite, particularly now after the zoomification of life during the pandemic, for physical presence, wherever it is safe to do so.

Matteo Bittanti: What’s next in the How to series?

David Blandy: I think that these are my last How to's for a while. It was emotionally draining to make the two new ones during lockdown, but they felt very necessary to complete at the time. Any new one would have to be a new start for the series in some way.

Matteo Bittanti: Is there anything you’d like to add?

David Blandy: I just wanted to thank you very much for your support over the years. Art is a solitary activity on the whole, and it has meant a lot to have such genuine interest in where my practice has been going. We stand at a precipice right now, with fascism on the rise across the world. It’s imperative that we work together to fight this hate, and work towards a communal vision for humanity where we have a chance to avoid the worst outcomes of the climate crisis. Extractavist capital has fed on fear to control vast swathes of the world. Somehow we have to show people that hope is possible.

How to Fly

digital video (1980 x 1080), color, sound, 6’ 23”, 2020, United Kingdom

Created by David Blandy, 2020

Courtesy of David Blandy, 2020

How to Fly was originally presented by John Hansard Gallery in Southampton as part of the Digital Array programme supported by the Barker-Mill Foundation.

Made with Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar games, 2013)