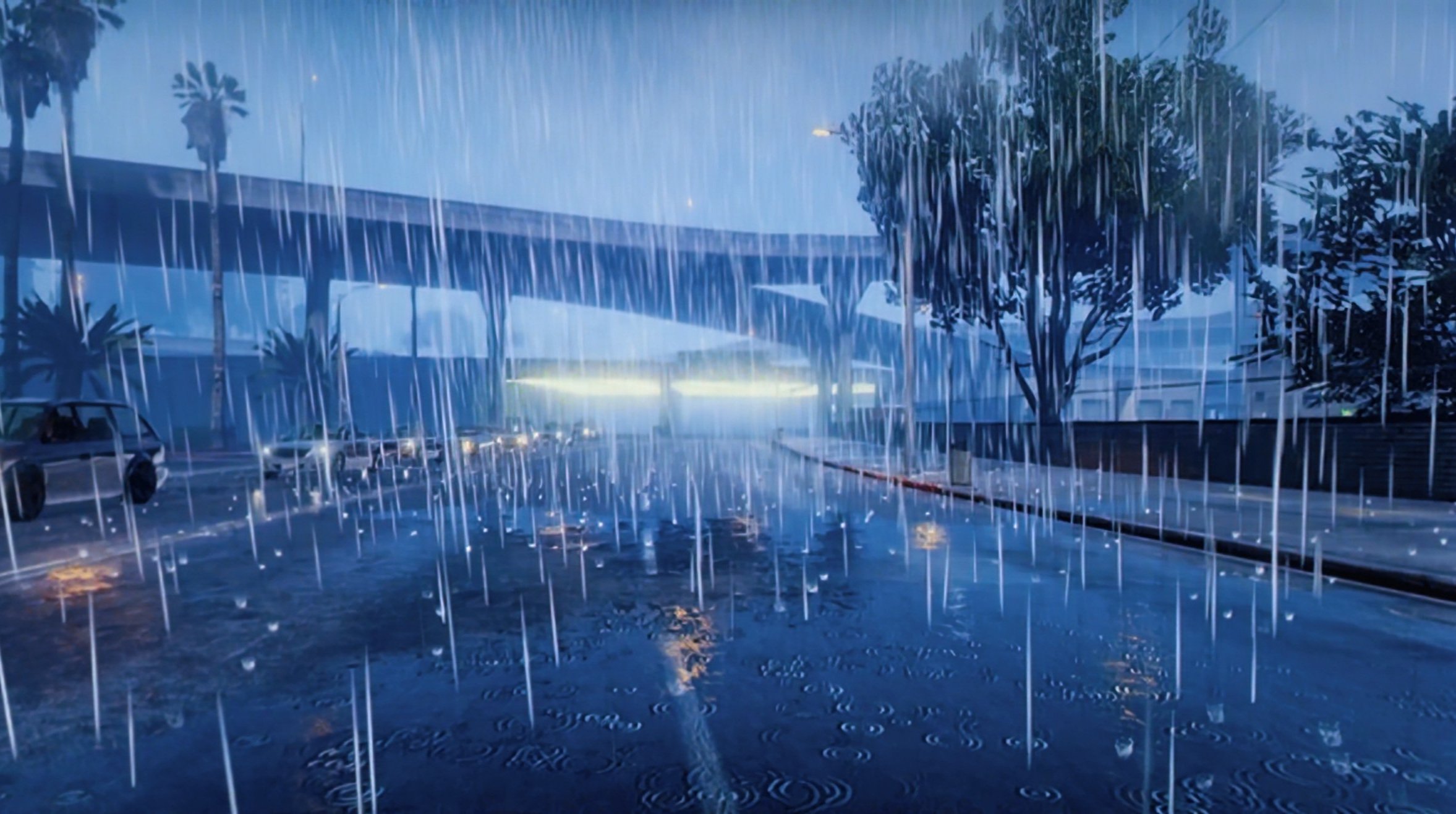

HYPER TIMELAPSE GTAV (CROSSROAD OF REALITIES)

digital video (1280 x 720), sound, color, 2’ 20”, 2014, Canada

Created by Benoit Paillé

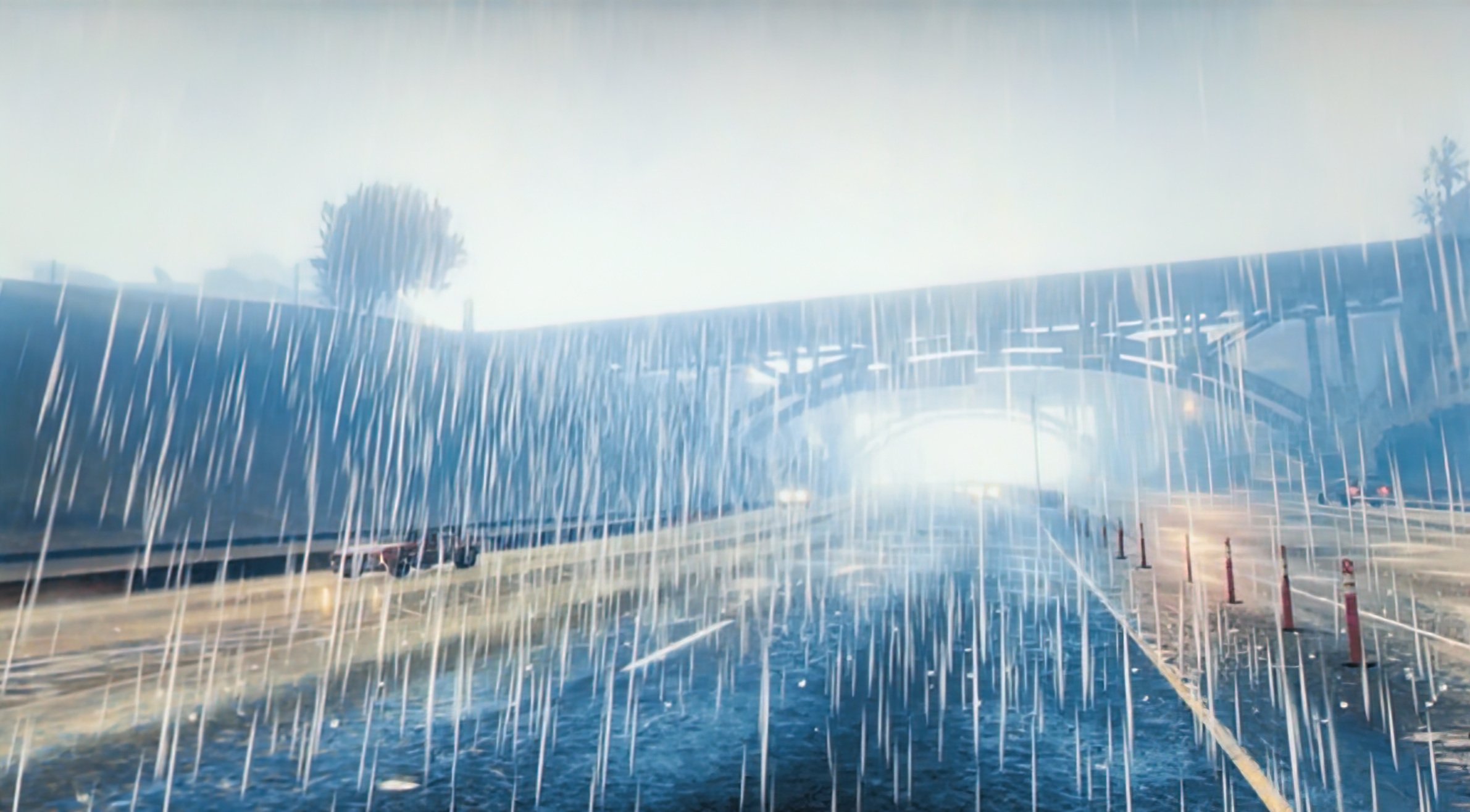

A time-lapse is a creative filming and video editing technique consisting in the active manipulation of the frame rate, that is, the number of images, or frames, that appear in a second of video. In most videos, the frame rate and playback speed coincide. In a time-lapse video, however, the frame rate is stretched out far more: when played back at average speed, time appears to be sped up. In 2014, Benoit Paillé created a seminal video time lapse of Grand Theft Auto V, as part of his investigation of photographic practices in video games, Crossroad of Realities. The result is a breathtaking taxi ride accompanied by an intense jazzy score.

Benoit Paillé is a self-taught French-Canadian photographer who lives and works in Québec, Canada. After studying biology for three years in a CÉGEP (a publicly funded college providing technical, academic, vocational or a mix of programs in Québec), he turned to the visual arts and decided to explore photography. According to his bio, Paillé sees himself as “a hyper realist painter” whose photographs document “an altered state of mind”. His work has been exhibited in Canada, Japan, Los Angeles, Barcelona, Moscow, and Ukraine. Among other things, he photographed speculative fiction writer William Gibson for the New Yorker magazine.

Matteo Bittanti: I read that one day you decided to drop everything, leave your home, and drive around in a camper. You said that this experience completely redefined your priorities: “It changed my life in the sense that it killed all notions of time and schedule for me. Before I used to go to school and have a regular job, but now, my time is open”. How’s your nomadic life nowadays?

Benoit Paillé: I’m still living in my camper. Unfortunately, I had an accident last winter. I was driving on a logging road in New Brunswick, Canada when I crashed my twelve tons truck in the ditch. All my stuff got trashed. So I have spent the last two months rebuilding my camper.

Matteo Bittanti: How did the pandemic affect you?

Benoit Paillé: Not so much, to be honest. I spent three to four months at a friend’s place. Otherwise, I am alone in the woods. I tend to avoid the city, if I can. So I was kind of removed from the action, so to speak.

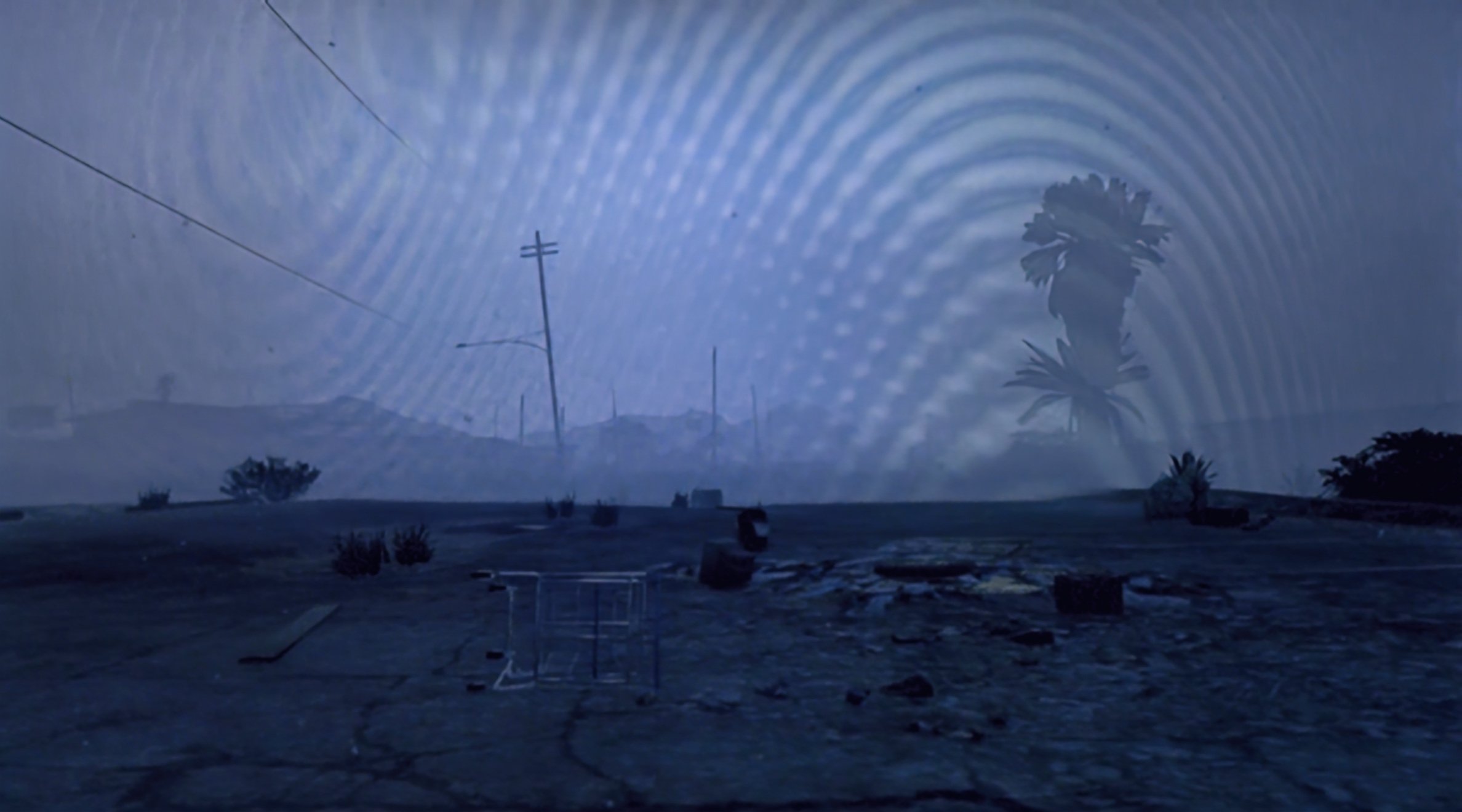

Matteo Bittanti: Crossroad of Realities is a landmark project for many different reasons. It was among the first to shine a light onto the artistic potential of photographic practices with(in) video games. But it was, above all, a commentary on the function and meaning of photography, as a medium and practice, after the so called digital turn and the rise of video games. It is clear from the very title your work emphasizes the idea that images, representation and simulation all constitute a “reality”, but what truly matters is the act of crossing, traversing, and eventually reaching a different layer. In other words, Crossroad of Realities is less about the “depicted reality” and more about the reality of seeing, and capturing realities through mechanical/digital means. Am I completely off track?

Benoit Paillé: Ah. Well, I need to provide some contextual information that may illuminate some aspects of the project. You see, at the time, I began smoking weed. And when that happened I started to ask myself a question. I was obsessed by trying to understand what kind of influence the virtual had on the so-called real life, that is, how the virtual influenced IRL, how simulacra — simulation of life — were becoming indistinguishable from life itself.

Ok, so, your question is very interesting. Because when I began my inquiry, I decided to investigate the crossroads of realities. It is exactly this crossing what interested me in the first place. So it’s not like you asked me why I used a DSLR to photograph video game images… For me, it was about questioning the very meaning of reality. As I mentioned before, when I was working on this project, I began experimenting with weed. I was like 28 years old. I was also going through a bad depression. I was kind of locked in my cave, so to speak, and I was not spending too much time out in the wild. That project took place in this kind of strange reality. So I asked myself: What is influencing reality nowadays? What are the effects of these simulacra on us? To answer these questions, I decided to go for a deep dive and I immersed myself in the world of San Andreas for days, actually weeks. I mean, that’s a world that feels almost real. And I was more interested in the space itself rather than the stories someone else wrote for me to experience. I started to pay attention to the details, like the lighting in the sky, which seemed like a glitch. I really wanted to look at that sort of things.

And you’re probably thinking, well, it’s impossible to look at the environment, how do you capture a moment without a camera? As you may remember, the PlayStation 3 version did not have a fully developed camera functionality, I mean, there’s an iPhone-like mode in the game, but it is very limited. Plus, you need an account [to Rockstar Games’ Social Club] to be able to take photos and then share them, so I decided to pursue a different strategy. For me it was much more interesting to create a time lapse by photographing the screen because when you photograph the screen, chromatic aberration and artifacts become evident, especially if you print them on a large canvas. I was really interested in documenting the hyperreal world through the mediation of the screen and through the lenses of a DSLR, among other things.

Matteo Bittanti: When did you first become interested in digital gaming? And how did you decide to bring your passion for photography into the virtual world?

Benoit Paillé: I began playing video games when I was very young. As a child, I was diagnosed with ADHD, Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder, and I found video games really captivating. When I was six or seven years old, I played Zelda on the Game Boy and got hooked. It’s not like I consciously decided that I was going to do a project with photography and video games or that I was going to do graffiti in the virtual world. It all really started like an experiment. I began looking around and that’s what I found. One thing led to another. For instance, if you start to take a photo of the screen, then you can do something else, like a time-lapse. It was an organic process. After that, I found myself super-immersed in the game. And I realized that it functions very differently from the real world, or rather, I was behaving very differently from how I operate in the real world… Within the game, my approach was… antithetical to work, antithetical to capitalism, if you know what I mean. It’s important to me that in the video game I would not replicate what I do in the real world where I go around, I take pictures, then I sell my pictures because selling pictures is how I make a living and so on. There needs to be a spark for me to take a picture. There was this conflict in me at the time. So, when I made this project, I was super immersed but at the same time I was not playing the game. I was more like playing with the game. I was just going around, looking for glitches and interesting things. I don’t know if I answered your question, LOL, but that’s what I was thinking at the time.

Matteo Bittanti: With the emergence of MMOs in the late Nineties, video games stopped being texts or artifacts and became more like persistent experiences that kept changing and evolving even when the player was not logged in. In the text accompanying your Crossroad of Realities project, you mention that you would often return to the same “places” and take photographs at different times of the day, using Adobe Lightroom to “develop” the resulting images. Video games became “open worlds”, spaces to traverse and navigate rather than stories to be “read”. It only made sense that people began to document their experiences with their virtual cameras… However, you went a step further, using “analog” means such as your DSLR camera or other tangible devices, like the cameras embedded in smartphones, tablets, and even portable consoles. Why was it so important for you to use analog means, among others, to document the digital?

Benoit Paillé: Yeah, it was really important to me to bring the analog inside the digital world. Or rather, not inside, but close… I mean, it’s like… The analog looking at the digital… Photographing the digital with the technologies and tools of the analog, in the studio, capturing images under a certain light, you know? My original plan was to print and enlarge the background, to produce a very large scale print of the photo I took in the game — call it a “screenshot” if you will — and I would re-photograph the printed screenshot with an analog camera, and then a Game Boy camera, but replicating in the studio the same light condition of the game, in order to ask a question: What is real? What is real now? Virtual worlds are becoming more real than real worlds. The real world is influenced by the virtual. Or perhaps, today the real can only be seen through the framing of the virtual… I don’t know… But these were the questions I was asking myself at the time. Maybe they sound a bit naive today, after all, I was so young back then… All I wanted to do was to bring the digital into the analog, to create an intersectional space where such a conflation was possible. Again, I was very high on weed, I was obsessed with Jean Baudrillard, and I thought I had created the perfect simulacrum…

Matteo Bittanti: Has photography, as a medium and art form, become obsolete? Is photography a dead medium, a mere fossil in Bruce Sterling’s archive of “novelties” from an anachronistic age? After all, many people born in the smartphone age think that photography is an “app”... What is the difference between a screenshot and a photograph in a fully digital world to you? And why was it so crucial to photograph the screen (and the hand holding the “camera”) rather than grab a screenshot of the virtual world when you were working on Crossroad of Realities?

Benoit Paillé: I wanted to foreground each ‘layer’ of reality before merging it with another, before lighting it up and setting up the real world, that is situating my hand and camera in front of the screen. Also, as I mentioned before, I made the project with the PlayStation 3 version of Grand Theft Auto, which had a very limited in-game camera mode, so it left some artifacts of the HUD game on the screen, a trace.

Matteo Bittanti: Your images are the result of an assemblage, culminating with the deliberate presence of hands and fingers within the frame. After all, digital comes from digitus, Latin for number but also finger. And yet, you cite Jean Baudrillard’s notion of simulacra in the opening statement of Crossroad of Realities. Are video games the quintessential example of simulacra? Is your finger not pointing at the moon, but rather at the act of pointing itself? Or are you giving the finger to those who naively speak about an “objective” reality that the camera is supposedly able to grasp and preserve forever?

Benoit Paillé: The paradigmatic example of simulacra is not the video game per se, but the influence of the video game onto the analog world. When the video game — which is a capitalistic form of entertainment centered on profit making — became an integral part of the gamer’s identity then the simulacra was fully enacted in real life, in the way people interact with each other.

Matteo Bittanti: In the fora dedicated to video game-based photography, artists and practitioners often debate the question of intellectual property. Legally speaking the “photographers” do not own the images taken in the virtual worlds: the companies are the legitimate owners of anything that players do in “their” games, “photographs” included for the same reason that taking a photograph in a shopping mall is explicitly forbidden and actively discouraged: it’s a private playground. After all, the players do not even legally “own” the games, they are simply “renting” them. Although almost nobody reads the End User License Agreements, players are legally bound to the whims and wishes of game companies. You do raise the question of ownership in your own work. To you, is there a qualitative difference between photographing a “concrete” desert in Arizona and a simulated desert in San Andreas? Would you say that you own the “photograph” you “shot” in the latter? Is game photography above all an act of appropriation?

Benoit Paillé: That was one of the key questions that prompted the project in the first place, and the fact that I shot the picture with a DSLR mechanical process, forced me to reflect more about the nature of my photo, but I am not sure. Fun fact: Epic Games made a feature about my project back then on their blog. The post received a million views or so, so it looks like they didn’t care much about copyright after all… I feel that the photograph of the simulated desert is real, not because I own it, but because I used a mechanical process to capture it. So, Crossroad of Realities was part of a larger project. My goal was to question the notion of the digital, the real, the digital within a Western cultural frame, and how these concepts influence each other. In other words, for me, those bits are all mine. And at the same time, they became like a memory. And when something became a memory, it’s yours. I mean, it’s your eye after all, even if they make you sign a user license agreement and blah, blah, blah, NDA agreements, and all that crap. I don’t know why, but I personally feel that I own the result of my work, but I understand the legal implications you are alluding to. That itself, may become a big game in the future. Say that I want to sell my project and now it’s value is two million dollars. And the company that made the game sues me for copyright infringement. I will go to court, but no, I won’t hate the company for that. I guess it’s just how things work. I own the idea of the project. Game photography can be an art of appropriation, but I thought that, because many were shooting as a documentary, a memory, a documentation of their in-game experience, they attached some kind of affective, emotional meaning. Frankly, the main difference between photographing the real desert and the simulated desert in San Andreas is that the latter was much easier to capture. In fact, when I began taking photographs of the screen, I was barricaded in my basement.

Matteo Bittanti: I would love to know more about the origins of Hyper Timelapse GTAV, which is also part of Crossroad of Realities. How is machinima related to your photographic practice? Did you make any other machinima after that?

Benoit Paillé: As I mentioned, the project was mainly about looking. It was also about recording a way of looking through photographic means. But not with the crappy camera that’s available within the game. I wanted to do all sorts of things that are very complicated in the game. How do you remove a character from the frame? That was just one of the issues that I faced when I made my time-lapse. I needed to figure out all sorts of things. For instance, where do I put the camera? How can I achieve my goal? I need to hold my controller firm, otherwise the result will look wrong in the next frame. Finally, I think I got it right, but it took so much work… And no, that was my first and last machinima to date. I don’t even know exactly what a machinima is, to be honest. The word is a bit alien to me. Afterwards, I went fully IRL, so to speak.

Matteo Bittanti: Interestingly, the jazz soundtrack that you chose for Hyper Timelapse GTAV — also known as GTA V Photographic Performance — was equally reviled and celebrated by the viewers, who debated its merits (or lack thereof) on Vimeo. Can you explain the rationale behind your music choice, i.e., Flat Earth Society’s “De Zoekactie”?

Benoit Paillé: Oh, that’s simply the kind of music I love. I thought it fit well. There’s no grand, rational explanation, to be honest. I still listen to this kind of music today. For this specific project, I thought the sound and the image went very well together. The rhythm perfectly accompany the sequence I made: the camera sometimes stops suddenly and the movement is a bit jerky, so to speak, likewise the music seems to stop and then start again.

HYPER TIMELAPSE GTAV (CROSSROAD OF REALITIES)

digital video (1280 x 720), sound, color, 2’ 20”, 2014, Canada

Created by Benoit Paillé

Music by Flat Earth Society, “De Zoekactie”

Special Thanks to Benoit Le Rouzès Ménard, Mary Lee St-Pierre, Daniel Delisle