JAKE

digital video (1680 x 1050), one channel, color, sound, 6’ 46”, 2023, Canada

Created by Benjamin Freedman

WORLD PREMIERE

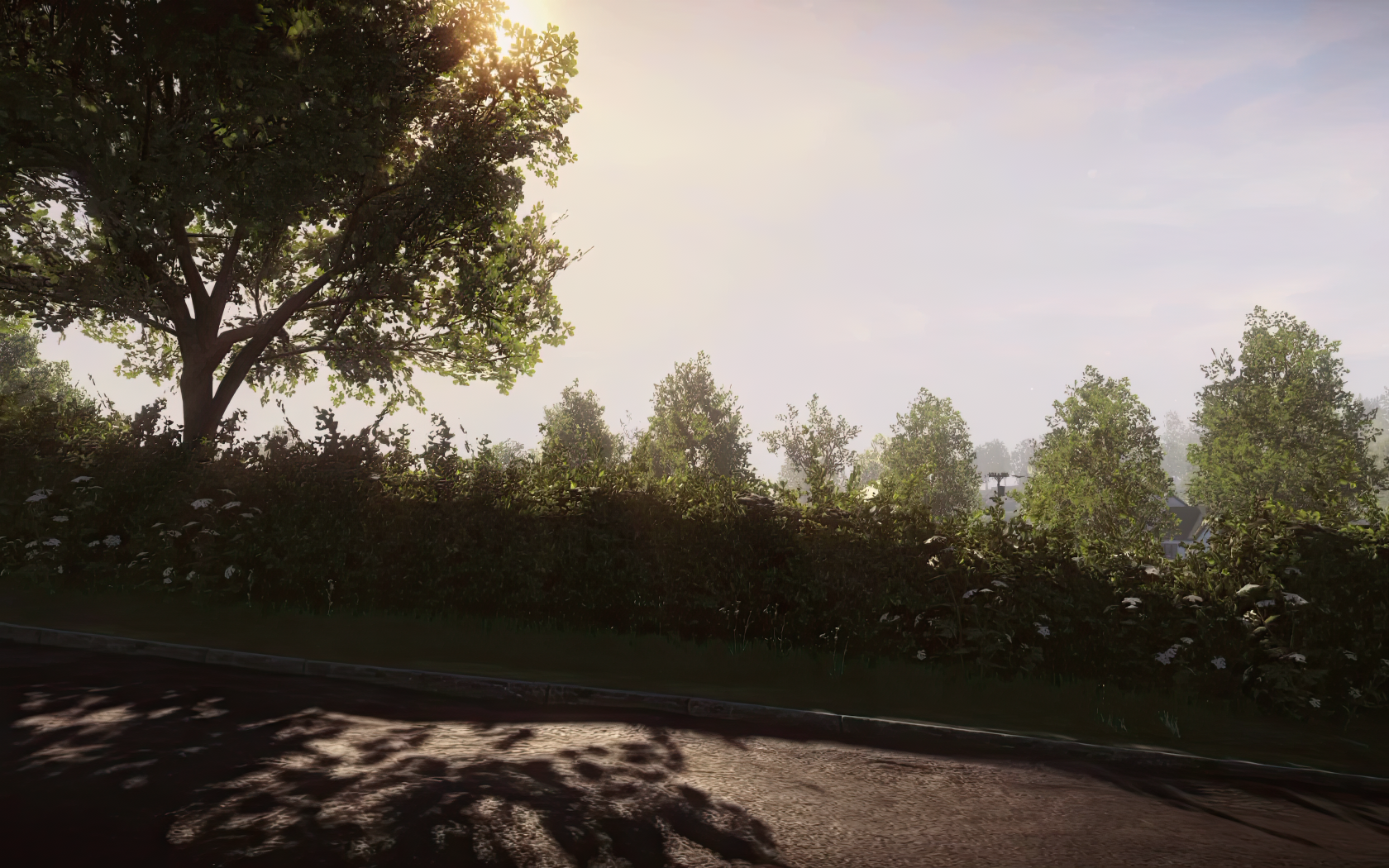

Jake is an experimental film that explores simulated environments and the inherent artificiality and fallibility of memory. Composed of footage captured in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture, a videogame set in a post-apocalyptic small town, the film presents semi photorealistic views that alternate between natural and domestic environments. Despite an effort towards realism, the footage remains uncanny as a disembodied voiceover of a young man plays overtop. Expressed in first person, the young man reminisces on his childhood memories that involve his family, the town itself and in particular, his first love named Jake. Written using OpenAI’s ChatGPT technology and recounted by a human actor, the narration eventually acknowledges that in spite of the town being simulated, like the nature of his memories of Jake, there is truth to the liminal space that divides reality and fiction.

Benjamin Freedman’s artistic practice spans multiple mediums, encompassing sculpture, video, photography and computer generated imagery with a marked interest in complex histories and the restorative potential of photographic research. Through his lens-based work, Freedman artfully reinterprets and disrupts the past, navigating the relative truths and deceptions inherent in the medium. Of particular note is his embrace of science fiction and horror visual vocabularies to expand his documentary projects, compellingly challenging the boundaries of the genre. Notably, Freedman self-published his first photography book in 2015, and has since exhibited extensively throughout the Greater Toronto area, including at Pumice Raft Gallery, Stephen Bulger Gallery, Ryerson Image Centre, 8eleven Gallery, Art Gallery of Mississauga, and Division Gallery, as well as internationally at the prestigious Aperture Foundation in New York City. Beyond his individual artistic pursuits, Freedman has also made significant contributions to the Toronto arts community, serving on steering committees for the Toronto Art Book Fair and SNAP! Live Auction, and as an artist advisory committee member for The Patch Project. He is currently pursuing a Master of Design, Photography at the École cantonal d’art Lausanne (ECAL) in Lausanne, Switzerland.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the origins of Jake? What is your relationship to the video game Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture? What drew you to this particular text as a source of inspiration, and how did it inform your creative process? What is your take on machinima? How did you first encounter machinima, and what attracted you to this genre of game-based video art? In what ways do you envision its potential for artistic expression, autofiction or meta-gaming, if any?

Benjamin Freedman: I started working on this project in October 2022 when I was interested in the photo realistic qualities of video games, specifically, how they have the potential to engross and implicate players in new worlds using immersive, photo realistic environments and assets. I’ve played videogames since the mid ‘90s, watching the evolution of the medium to what it has become today, so I was excited to blend my passion for art making with gaming. Originally, I was specifically focused on the use of sunlight in videogames. The sun is an essential ingredient in the making of photographs in the physical world, and while it is all around us, we cannot look directly at it. The sun’s presence is mostly ornamental in the context of a videogame but is an essential ingredient for the sake of realism and in these digital environments, we can stare directly at it without any physical repercussions. This interest served as a starting point for my research and I immediately selected Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture due to the quality of the lighting and environments. I’ve always been a big fan of The Chinese Room since they released Dear Esther when I first played it in 2012 and was excited to play Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture when it was released in 2015. The story itself revolves around memory which is rendered as light spectres throughout a small town that the player is instructed to interact with. The game is set in the aftermath of a mysterious apocalyptic event and the town is void of any humans aside from their personal belongings left behind and these memory spectres. Already I was thinking about the game’s inherent connection to the medium of photography which is so intrinsically linked with concepts of memory, the passage of time and the flattening of space. It was only after replaying it for this film did I come to realize that the rapturous event in the videogame was due to a kind of otherworldly presence that is referred to as “The Pattern,” and it travels through electronic devices. It’s a strange technological deity that dematerializes the townspeople which I thought reflected the current paranoia surrounding A.I. models.

The concept for the film naturally developed as I started creating static video portraits of the many environments found in the game. They’re so atmospheric and haunting and it inspired in me a deep sense of nostalgia – an emotion I’ve explored in many of my other projects. In early December, I started playing with the newly released ChatGPT. I discussed with it my project and asked it what it thought of simulated spaces. Throughout the course of the exchange with ChatGPT, I started to experience a suspension of disbelief. Our conversation felt natural and uncannily real – feelings I so often feel while playing videogames. It became only natural to try and weave these two elements together and that is how Jake came to be.

I first encountered machinima through the work of Skawennati, a Mohawk multimedia artist based in Montreal. She had an exhibition at my Alma mater, Toronto Metropolitan University, at The Image Centre. Her research is primarily focused on indigenous histories and she uses Second Life as a vehicle to re-enact, revisit, and recode the past, which I found incredibly moving. In my own practice, I’ve always been interested in using photography as a pseudo archeological tool to explore hidden histories’ and fictions’ unique ability to emphasize and re-explore the past. This framework plus my studies at ECAL really guided me towards exploring machinima in my own practice. More specifically, using games to explore memory was useful to think about the universality of these themes. To repurpose environments that other humans have made allows for a different reading of the work in so far as the work is inherently co-authored. I am not working in a vacuum. By recontextualizing existing visuals, I’m able to highlight a shared experience that is not mine alone.

Matteo Bittanti: Appropriation and recontextualization are two of the main features of machinima, indeed. Although video game images may seem cartoonish on the screen, they evoke complex meanings. As a lens-based artist with a keen interest in the complexities of photographic research, you have delved into various forms of visual media in the past decade. With the increasing prevalence of video games as a medium for artistic expression, there has been a burgeoning interest in the art of in-game photography, a practice that utilizes game engines and virtual environments to create works that blur the boundaries between photography and digital art. As an artist who works extensively with photography, what is your take on this phenomenon, and how has it influenced your practice? When did you first encounter in-game photography, and what drew you to explore its artistic potential? Would you say that, with its unique blend of real-world photographic techniques and digital manipulation, in-game photography presents an intriguing challenge to traditional photography practices, opening up exciting new avenues for creative expression, or is it just an experiment, or, worse, a gimmick?

Benjamin Freedman: I often liken myself to a chameleon. Depending on what I’m interested in, I enjoy assuming new roles. Photography is such a slippery medium, so perspective means a lot to me and shapeshifting has been a helpful strategy to dig into the subject matter and play. I’ve been a scientist, a botanist, a monster, a sculptor, a child, to name a few. The medium allows me to become anyone I need to be, but it is also a skeleton key that grants me access to many unique environments. Videogames function similarly. You’re thrust into the headspace of a character who might have completely different origins, motivations, interests than your own and yet, to succeed at the game, you are forced to inhabit them for a set amount of time. You must surrender to their perspective.

I come from a relatively traditional photographic education. I completed my Bachelors in 2013. In “photo years,” a lot has happened from then till now! My work was all shot on film in large and medium formats. I was trained to take photographs in a traditional way. I believe my interest in this mode of image making will always stay with me, however, through the encouragement of my professors at ECAL (in particular Marco De Mutiis of Fotomuseum Winterthur) my understanding of what photography is, and most excitingly, can be, has broadened. Photography, thankfully, is not one thing but many. It has become a language that slips into many key areas of modern life and it is important that I evolve with it.

At the risk of sounding trite, my interest in photography is to better understand myself and the world at large. My mother is a cognitive psychologist and I have engaged in many conversations with her about how our brains filter and interpret the infinite stimuli of the world that continually bombard us. The world can be processed and understood as a collage of symbols and codes. With videogames, we can go deeper. They are crafted by humans to reflect the human condition. Not to draw an exact parallel here but I think of the collage works by neo Dadaists like Robert Rauschenberg who remixed printed ephemera made by others to explore the collective unconscious. This is also how I would classify machinima. Photography was useful to the Dadaists and I think videogames can be useful to photographers. We don’t need to restrict ourselves to only the physical world – we are making new worlds in the form of the videogame and I don’t think in-game photography should be viewed as a challenge – surely traditional modes of image making aren’t going anywhere anytime soon. In-game photography is just another avenue to explore the same fundamental questions all artwork ultimately aspires to answer.

Matteo Bittanti: Jake is about many things, but perhaps above all, false memories. According to psychoanalytic theory, false memories are a type of unconscious defense mechanism called repression. Repression involves unconsciously pushing unacceptable thoughts, feelings, or memories out of conscious awareness to protect oneself from emotional pain or anxiety. False memories may occur when repressed thoughts or memories are recalled, but are not entirely accurate, and are often distorted or fabricated because of unconscious processes such as fantasy or wish fulfillment. These memories may arise to fill in gaps or inconsistencies in memory or to defend against feelings of guilt, shame, or anxiety. Interestingly, you used found footage - in the form of video game scenes and gameplay - to re-construct a memory that may be or may be not “true”, so in a sense, the memory is not just false, but perhaps counterfeited or entirely fabricated. I find myself often reminiscing about vivid experiences that I had inside the virtual worlds of games, while sometimes I struggle to remember what happened to me just a few days ago, in the so-called IRL. This apparent paradox informs one of my all-time-favorite game-based video artworks, that is, A Man Digging (2013) by Jon Rafman. If memories are simulations, are video games ludic réveries, or perhaps lucid dreams? Is this why you picked Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture to create Jake?

Benjamin Freedman: Yes, that’s correct. For the past year, I’ve been very interested in this notion of false memories through my experimentation with CGI technology. I’ve been creating numerous photographs that are entirely constructed in a computer to recreate my own memories in an uncanny yet semi photo-realistic fashion. Memories are foundational building blocks for our identities and provide a framework for how we operate in the world. My mother’s PhD thesis discussed the phenomenon of positively distorting memories as a healthy strategy for effectively coping and she would argue that we don’t only distort memories that are traumatic. Sometimes the falsification can be relatively inconspicuous, applied to multiple events throughout the day.

Recently, I started reading Tim Carpenter’s newest book entitled To Photograph is to Learn How to Die and in the very first chapter, he discusses the relationship between the mind and the world saying “If we deceive ourselves by longing for (and believing in) invented worlds, we are also bound to misrepresent the world we actually inhabit. Because we must rely entirely on internal capacities to generate meaning, our selves are basically the sum of the ever-changing relationships between mind and world. Our challenge is to observe and know these representations–without delusion–even if this scrutiny necessarily reopens the tender underlying wound.” (Carpenter, 19). This is the role of the artist to parse out the distinction between the inner and outer world. Our memories have immense power over who we become but they are immensely susceptible to a kind of psychic erosion. Alternatively, we are also capable of remedying our internal feelings and attitudes to the external world on a biological level thanks to neural plasticity. While Carpenter is referring to general misreading of the world through our imagination, it is interesting to re-read this passage through the lens of videogames. In Jake, the memory is entirely fabricated. I collaborated with ChatGPT to write a script that recalls specific memories that involve romance, childhood, family drama. I wanted to play with the language model and construct a narrative that, despite its fiction, alluded to real emotional experiences while embracing clichéd notions of love – an experience that is (hopefully) highly relatable to audiences. In this way, the film triggers viewers to reflect on their own memories, their own past and consider memory itself as a kind of simulation. With regards to our own memories, regardless of whether-or-not they happened, it’s the way we remember them that counts. I believe this becomes even more complicated for highly visual people who experience memories as images. Given the image saturated world we are currently living in, I sometimes wonder if it is easier to accidentally misremember. For example, I’ve had moments where I reflect on a memory and wonder if it truly happened to me or if I’d seen it in a movie. Ultimately, does it actually matter?

Some of my fondest childhood memories took place in virtual environments. I played a lot of World of Warcraft back in 2004 and built a vibrant social community online through it. I think play can be a potent agent in the construction of memory, especially when it comes to video games whereby to play one must first understand the rules. It is not a passive experience. It involves both the body and the mind which could explain why memories formed while playing videogames are so ‘sticky’. Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture feels very emotionally sticky and through its use of natural light and detailed interiors, it activates a nostalgic part of my brain and I hope that it does the same for others as well.

Matteo Bittanti: In his book New Dark Age, which was recently reissued in a new edition, James Bridle shares a vision for the future of human-computer interactions inspired by the concept of “centaur chess,” the idea that humans and computers work collaboratively rather than antagonistically to achieve unprecedented levels of success. While computers have proven themselves to be unbeatable in games like chess, former world champion Garry Kasparov has developed a counter-strategy that leverages the unique strengths of both humans and computers to defeat even the most advanced AI opponents. Drawing on this example, Bridle argues that a new paradigm of “guardianship” could emerge, in which humans and machines work together to solve a variety of issues. Can we extend this metaphor to art making? Your machinima Jake is the outcome of a collaboration between humans (namely you, Benjamin Freedman, Charles Hutching, and Chris Berry) and machines (above all, ChatGPT). Going forward, do you see this kind of convergence as inevitable or as an exception, an anomaly? How instrumental was ChatGTP in the making of this work?

Benjamin Freedman: Absolutely! I understand the current existential dread that AI has inspired in us. It is scary to be at the beginning of a paradigm shift but ultimately, these are all just tools. At least in the case of making Jake, while the text was created using ChatGPT, I was heavily involved. Not only was I prompting the language model, I also heavily edited the text. ChatGPT gathers text from countless online sources and the way I view it, presents a kind of text-based collage or rather a portrait of our collective unconscious. Why shouldn’t I involve myself as I’m already implicated in the dataset. For the most part, the responses ChatGPT provided me were interesting but it became highly repetitive and superficial. I continuously re-fed it prompts, questions, clarifications and that’s where the real value of the process was. I couldn’t just copy paste the answers, I needed to think of it as a tool to play with.

After the text was finalized, I fed it through an “A.I.” text to voice program for the voice over but the results were unconvincing and not interesting. The voice was uncanny but easily discernible as a computer-generated voiceover which completely removed the element of suspended disbelief that I think is vital to the work. I decided to work with a voice actor to return that element to the film. Thinking about how an actor can embody the text, generated through ChatGPT, was very interesting. An actor, while being aware of the fiction, needs to disregard this knowledge and sell the lie. When we recorded the narration together, we did so in a professional sound studio in a famous Canadian television broadcasting building which immediately felt synchronistic. We were in a building that is responsible for the telling of stories, of sharing images, ours just happened to be written by a language model with footage provided by a videogame, constructed by humans. I don’t think this kind of robot/human collaboration is an anomaly but is simply a new way of working and it excites me more than it scares me. I think a lot will develop over the next two years so hopefully I’m not wrong!

Matteo Bittanti: The playful and imaginative nature of toy culture has long been a subject of fascination for many artists, and your work certainly reflects this sensibility. From the intricate dioramas of Spectral Geographies to the game-based video art of not to mention the surrealist game par excellence, Exquisite Corpse, your oeuvre is marked by a ludic aesthetic. At the heart of this approach is a deep engagement with the possibilities of play, which allows you to explore complex themes and ideas in ways that are both accessible and engaging. How do you see this dialogue between the artist and the ludic, which was discussed, among others, by Walter Benjamin?

Benjamin Freedman: I think humans are inherently wired to play, therefore, art making is a kind of play for me. While I enjoy the theoretical and contemplative dimension of art making, what makes me inspired to wake up and want to work is the promise of play. As an artist, I believe it’s my role to look at the world as if I’m hanging upside down on monkey bars. My father is almost in his 80s and still maintains a childlike perspective on the world more than anyone I know! I think it’s his sense of curiosity for learning that gives him his youthful spirit and now inspires him to paint and write poetry. I believe he gave me a little of this. I think looking at the world as a child is a helpful way to make art and, as you pointed out, has become a distinguishable style of mine. More obviously in my new work made in CGI and photographed from the perspective of a child, I’m very interested in the aesthetic of this perspective. How the world physically looks at a reduced height where scale is strange and uncanny. What children choose to look at. Everyone remembers what it was like to be a child but sadly we forget how to think like one. I use art production as an excuse to think like a child and to learn something new. Whether that’s about me, about the world, or more plainly – just about learning a new skill. I think that sense of curiosity is attractive to audiences because it involves them in a game of discovery.

JAKE

digital video (1680 x 1050), one channel, color, sound, 6’ 46”, 2023, Canada

Created by Benjamin Freedman

Directed, produced, written by: Benjamin Freedman

Voice by Charles Hutchings

Audio by Chris Berry

Script created collaboratively with OpenSource, ChatGPT

All videogame footage captured in Everybody’s Gone to the Rapture (The Chinese Room, 2016)

VRAL would like to thank Marco De Mutiis