Hey Plastic God please don’t save the Robotic King, Let him drown in Acidic Anesthetic

single-channel digital video, color, sound 5’ 33”, 2023, Iran/Greece

Created by Babak Ahteshamipour

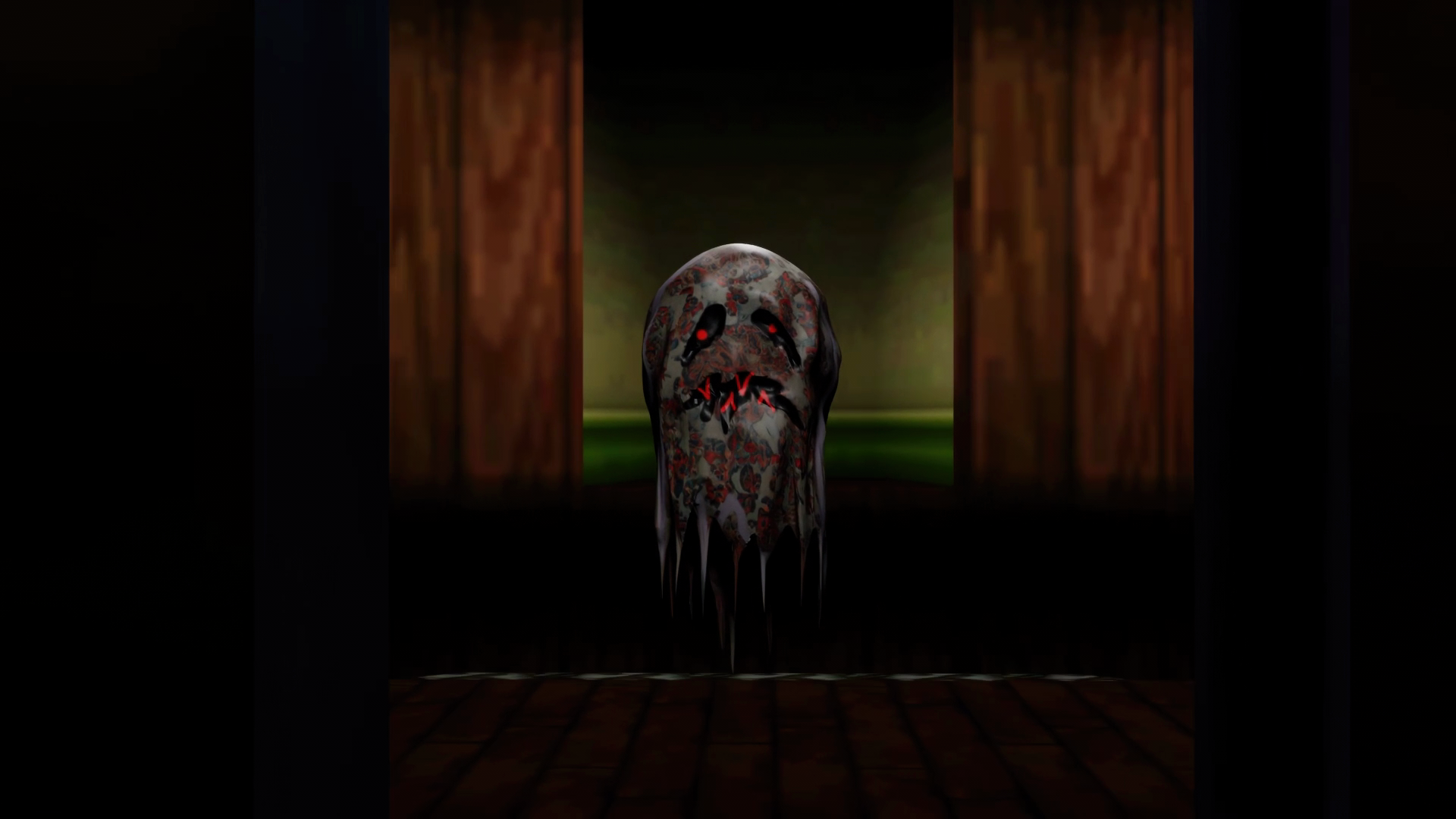

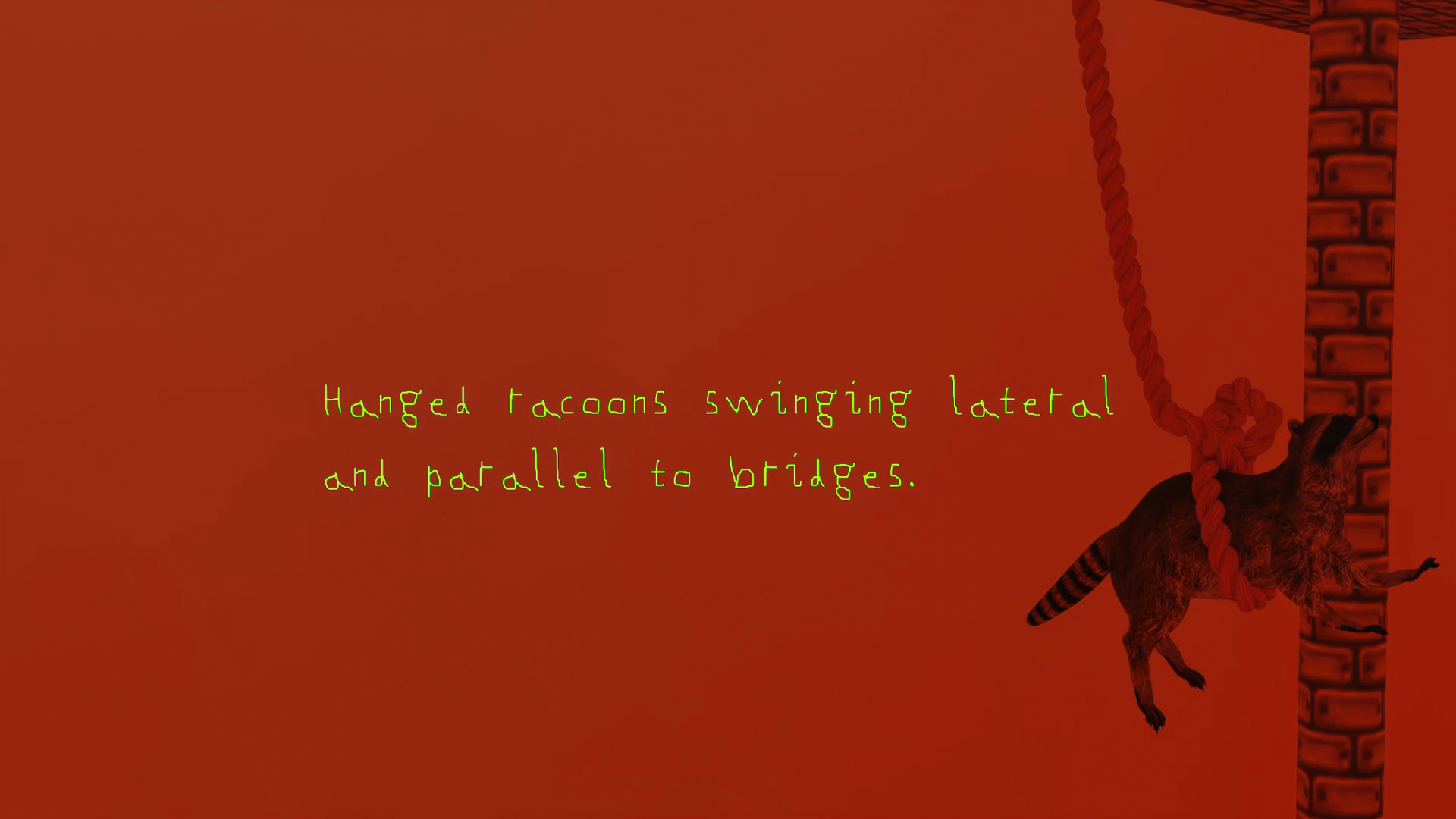

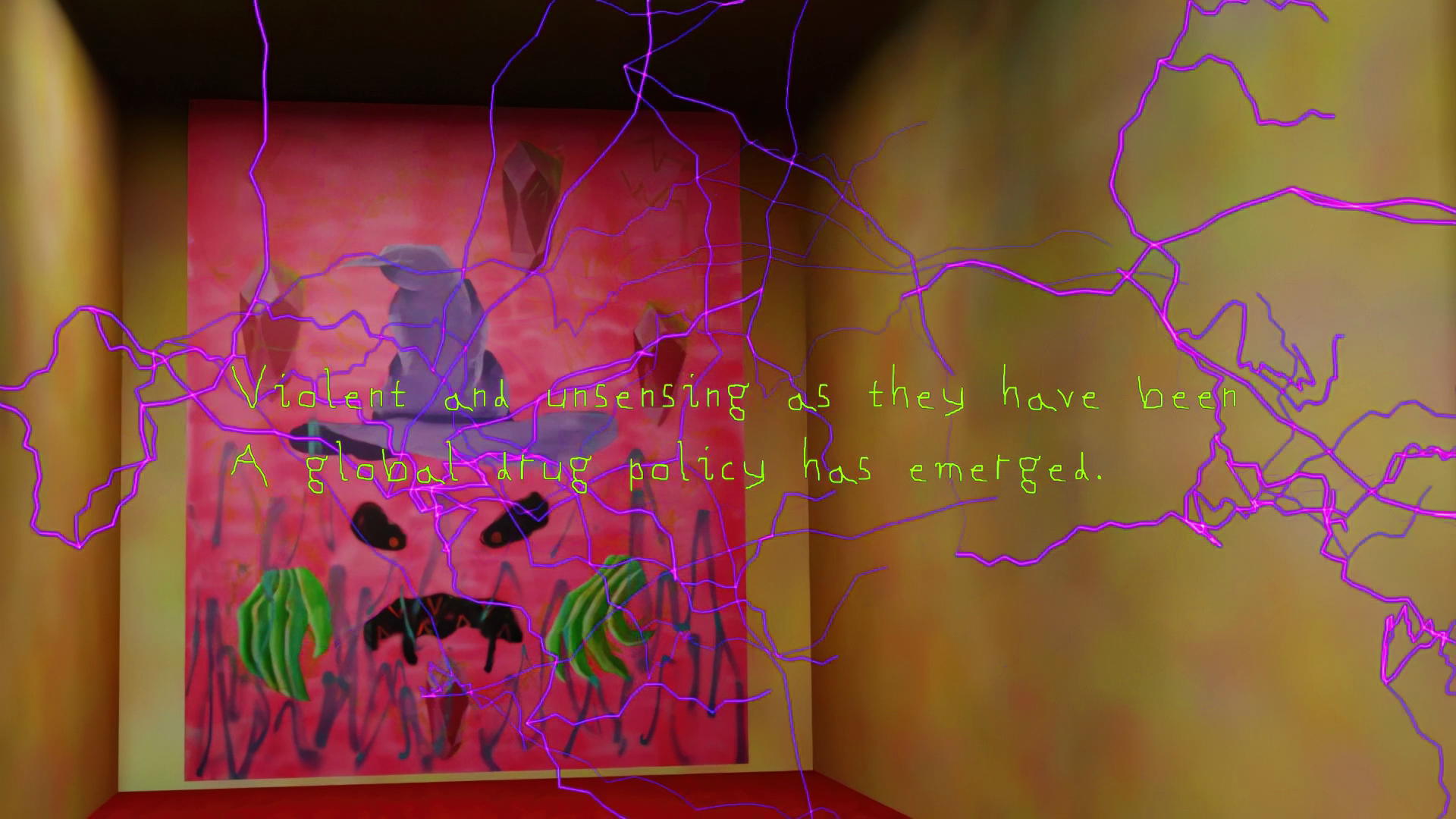

Hey Plastic God please don’t save the Robotic King, Let him drown in Acidic Anesthetic explores the mental disintegration of a cyber-king plagued by hallucinations fueled by narcissism, megalomania, and a relentless desire for power and grandeur who finds himself spiraling into a self-created abyss. The video juxtaposes Ahteshamipour’s real-life paintings with digital landscapes from Super Mario 64 and Super Mario 64 DS video games, thus blurring the lines between physical and digital realities. This artistic choice symbolizes the ever-growing influence of digitalization on our daily lives and challenges the separation between these two realms, and the predominant androcentric narratives in gaming culture.

Babak Ahteshamipour is an interdisciplinary artist, writer and musician based in Athens, Greece with a background in mining and materials engineering. His practice is based on the collision of the virtual vs the actual, aimed at correlating topics from cyberspace to ecology and politics to identity, exploring them via gaming, online and pop subcultures with a focus on themes of coexistence and simultaneity. Ahteshamipour’’s work has been presented at festivals, venues, galleries and spaces, museums and institutes such as Centre Pompidou, New Art City, The Wrong, Neo Shibuya TV, University of North Texas, The Networked Imagination Laboratory (McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario), Biquini Wax ESP, Experimental Sound Studio, Milan Machinima Festival, [ANTI]MATERIA, ArtSect Gallery, and Ametric Festival. Ahteshamipour has released music on the independent cassette label Industrial Coast and on the cassette label Jollies. His music has been played on radio stations such as Fade Radio, Radio Raheem, and Radio alHara. He has performed and shared the stage with artists such as HELM, Zoviet France, The Nam Shub of Enki, Gaël Segalen, Sister Overdrive, and Kiriakos Spirou. He has created video clips for artists such as Fire-Toolz, Digifae, and B.MICHAEEL. His work has been featured on magazines such as CTM Festival’’s magazine, KIBLIND, VRAL (Milan Machinima Festival), und. Athens, Our Culture Magazine and ATTN: Magazine.

Matteo Bittanti: I would like to begin by asking you a few questions about your recent essay “Misplaced and Displaced, but Never out of Place” exploring the nature, use, and symbolism of portals in video games and more linear narratives. You write how portals usually represent transition, demarcation, and access between worlds, dimensions, timelines, or planes of existence. At the same time, you connect the appeal of multiverses to contemporary pessimism, conspiracy theories, and end-times narratives. What are the potential risks or downsides related to this kind of multiversal thinking? Is it memetic and contagious, like a virus?

Babak Ahteshamipour: I don’t think we should speak in terms of downsides or upsides, each person or collective interacts dissimilarly with it, sometimes it is memefied, other times it gets absorbed and has the potential of becoming parasitic. I believe these multiversal discourses are connected to escapism, which is the point of the essay and through these short-term escapes each person finds a moment of solitude, tranquility and connection that could help them out with the real world — something underscored also in my work In Search of the Banned Dictionaries that contain the Words for the Things You Wish you could Express but You are Unable to With Common Words, escaping to virtual worlds while reality falls apart. When these escapist fantasies become fetishized online — or offline — subcultures, they predominate one’s identity. An offline example could be live action role playing games where one merges with their fictional identity. This over-identification is excessively common among hardcore gamers or role players when they get obsessed over their virtual avatars or online personas and they become more like their avatar rather than themselves. Now take this and convert into a dark, twisted underground online subculture or a hub of internet subculture like incels and 4chan where they resort online to expose parts of themselves that hide in plain sight in real life (RL). Or take the example of online personas such as cosplayers, e-girls, fembois, waifus or influencers which have become one with their online identities, something indicated by Xleepyfay & Aemmonia: The Xenofeminist Hauntology. Their online identities have penetrated into their offline life to a degree that they cannot distinguish reality from virtuality. They would spend hours per day over their phone or having discussions about online personas or looking forward to getting back in front of a screen and entering their cyber-kingdom. Cyberspace, social media and online communities provide shelter, trust, a safe zone and a strong community through which a person can either be more themselves or can find new identities and ideologies that make sense to them and feel connected to. But that doesn’t mean that there aren’t darker paths either, as mentioned. After all portals lead to all sorts of otherworldly dimensions, some of them have demons, some dragons, some fairies and others just trees. What remains essential is the magnitude to which a person’s critical thinking, common sense and defense mechanisms can be sculpted, manipulated and hammered by propaganda, conspiracy theories and extremist ideologies. Good or bad, correct or wrong are subjective constructs. Instead there are different agendas that try to force their will on others since each one’s truth is only truth: the emergence of post-truth. But in reality what works best and respectfully may be conversation. From my observations lately these multiverses have shut down their gates, there’s no internal discourse criticizing their own dogmatism and are in no position to approach other communities or political agendas to have conversations.

Matteo Bittanti: In the same essay, you describe how portals between the lands of the living and dead are represented by ghostly sounds in games. There’s a long tradition of associating (once) emerging technologies with opening portals to the supernatural, like spiritualist photography or films like Poltergeist, not to mention the most recent ‘desktop cinema’ horror subgenre. Do you think this supernatural symbolism around portals and mediums still resonates in modern technologies, including digital games, vr, and ar? Is the association with the supernatural related to our tendency to connote advanced technology as a form of magic, to paraphrase Arthur C. Clarke?

Babak Ahteshamipour: I wouldn’t say there is anything magical about technology in terms of black magic, sorcery or occult. Perhaps futuristic. In my opinion the way advanced technology is being received and depicted in mainstream media is the opposite of supernatural. It’s purely technocracy and advanced science. There is bold anthropocentrism at play, especially with AI. Anything technological that has the potential of having autonomy from a printing machine to an advanced AI are doomed and haunted by anthropocentrism, their gazes are based on the human gaze. The machine gaze has not yet been liberated from the human gaze. They are undead entities brought to life based on how humans perceive and make sense of reality. They are trained based on anthropocentric symbolic constructs, languages, biases, material creations, scientific knowledge, culture, aesthetics and so on. The machine’s gaze has boundless potentials, can provide an assemblage of alternatives, forge juvenile pathways and perceive reality from unconventional angles. This is reminiscent to the vague, blurry and blunt images that AIs such as DALL·E generated when firstly released. Those murky and puzzling results were the machine’s gaze forging new assemblages of narratives. But of course over the course of years AIs such as Midjourney have been enslaved and trained to generate hyperrealistic crystal clear images that succumb to technocapitalism and production: AI as just another tool. This is something that I explored with a recent work of mine entitled In Defence of the Undead where I had an AI generate low resolution images inspired by Otaku culture. Through its production process I investigated the hyper-sexualization perceived in Otaku culture and fetishization of machines. The images were purposefully created in collaboration with AI, since I perceive a gap between the machine's gaze and the operator's gaze that generates a parallel dimension where their gazes are in conversation. How I perceive their differentiations and contradictions is through a term coined by Slavoj Žižek, the parallax gap or minimal difference: “The paradox is here a very precise one: it is at the very point at which a pure difference emerges — a difference which is no longer a difference between two positively existing objects, but a minimal difference which divides one and the same object from itself — that this difference “as such” immediately coincides with an unfathomable object: in contrast to a mere difference between objects, the pure difference is itself an object. Another name for the parallax gap is therefore minimal difference, a “pure” difference which cannot be grounded in positive substantial properties.” Thus the only magical depiction of technology that I find relevant is super-advanced technological devices depicted in games or cinema such as a particle sucker, a black hole generator, a hologram, a time machine or an autonomous AI, rendered free from anthropocentrism.

Matteo Bittanti: With your latest video work, you’ve remastered an earlier piece of video art. I find the concept of an artist remastering or reinterpreting their own past work to be really fascinating. Could you discuss more about what motivated you to revisit this earlier artwork and remake it? Were you hoping to reach a new audience, gain a new perspective on the themes, or simply experiment with translating the visual language into a new form? More broadly, do you see artistic self-remastering or remaking your own creations in new or at least different media as a vital part of your practice?

Babak Ahteshamipour: What made me revisit this piece is that during the past year I’ve worked on some video clips for musicians such as Fire-Toolz, Digifae and B.MICHAEEL and the 3D movie Click Esc to Exit the Data Based Molecular Prison called Existence in collaboration with Aggeliki Germakopolou that resulted in developing my 3D skills. Hey Plastic God… was the first 3D clip I did and I hated how it looked, so I wanted to update it since I love the concept of it and it was the first track of my first album. I tried to keep the some lo-fi qualities from the original version but in an furnished sense. It now connects to me in more profound ways. I’ve always had this approach as an artist. I would create things that had an interesting concept, be it a painting or a video or a text or musical composition that I felt something was off about it. I’d leave it and get back to it to put the finishing touches in the future. I see artistic creations, photos or clothes as stratified marks in space-time that become statements or artifacts that reflect a part of our then Self. I haven’t painted for the past two years and going back to these paintings made me nostalgic and sentimental. Evolving is an ever-changing procedure and visiting the past can be a reminder of who one was, is and can potentially be.

Matteo Bittanti: In your latest video work, you still juxtapose physical paintings with digital game spaces from Super Mario 64, obsessively framing and re-framing the artworks across mediums. This interplay between physical and digital representations is an ongoing exploration in your practice. How do you view the relationship between the tangible painting and its digital rendering in the game world? Rather than asking which is more “real” (they both are, obviously), I’m curious about how you see these different instantiations interacting, informing and perhaps completing one another. Is it a parallel co-existence, a blurring of boundaries, or something more complex? Your framing devices point to a constant oscillation between physical and virtual that I’d love for you to unpack further. Perhaps this contextualization could be helpful: I have been reading ebooks for many years but I still feel the need to purchase a physical copy of specific text: the authors I venerate, a graphic novel, an art catalog. The printed book becomes a sculptural object, a monument, the idealized package of information that I have consumed on an ebook reader or tablet The physical book occupies physical space, has some weight, it exists outside of a screen, whereas the ebook (or the audiobook, for that matter) is a file that I consume, highlight, incorporate into another text, a school lecture, an essay, an artist statement, and so on. Going back to my original, and frankly convoluted, question: can you discuss the relationship between the physical artifact you produce, be it a painting, a sculpture, an installation, and its virtual counterpart?

Babak Ahteshamipour: Honestly whenever I think of a possible work or project, I have no clues whether it will end up being an image, a 3D or music, they are all entangled in my mind. What is important for me is the universe behind it and what it represents. For these specific paintings it’s very funny since they are already inspired by video game characters or entities that I ended up creating in 3D! When I see the painting next to the 3D I really cannot decide which I prefer, the painting or the 3D, but I know that I cannot imagine one without the other, they complete each other. This initial idea of creating these 3D renditions for these paintings came to life when me and Nathan Harper started discussing the creation of the virtual exhibition The Lost Woods, where some of these characters and paintings occupy the space. To complete this circle me and Nathan intend to revisit The Lost Woods to remaster it and update my characters with their latest versions that appear in the remastered version of Hey Plastic God… and Click Esc to….

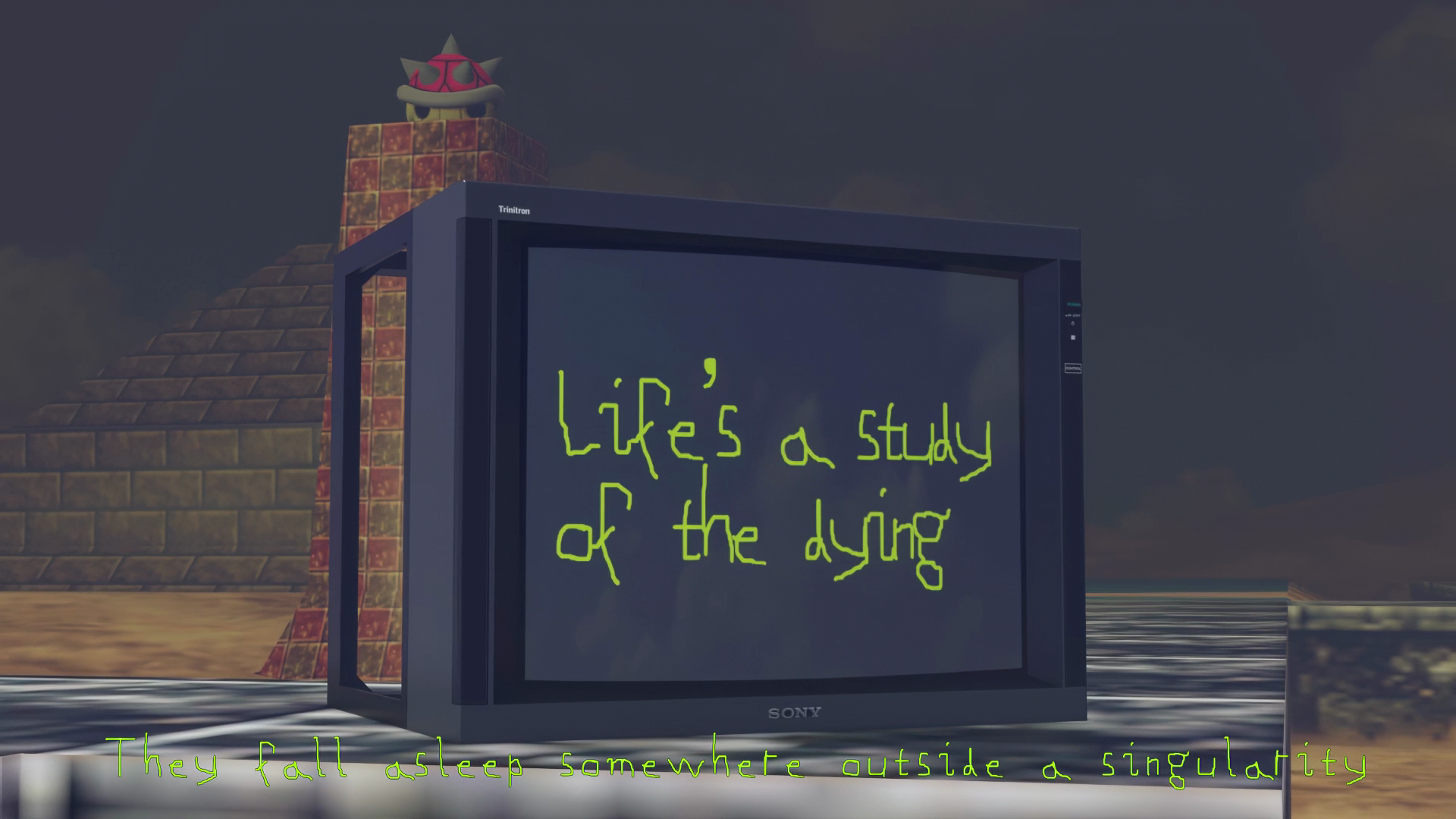

I have a terrible relationship with material objects. I sold all my musical gear last year and switched to softwares. I only buy books that I know I need and will read them. I do extensive research before buying a book and become attached before even purchasing it. After a while that connection is gone, I give it away to a friend or a library and download it as an ebook. This references to what I said earlier about evolving and moving on from past obsessions, relationships and interests. I feel like my goal in life is to find myself and keep along some material objects and creations that will trace to those past segments of myself that I still feel connected to. I even give away, sell or gift my paintings or prints after a certain time. I sometimes keep a few material objects from the past that I still adore and am attached to since how I perceive these stratified fragments of space-time is as if they are traces of a past self. Occasionally these forged material relationships are inevitable and bring one closer to their inner truth in order to reach their potential self — as long as it’s not zombified consumerism. I recently did a series of posters entitled Stimulated Simulations with loading screens from video games to criticize new age lifestyle and matras provided by capitalism regarding finding meaning while one’s life force is being sucked by the fangs of capitalism. Meaning is absent in this context, one can be stuck forever in transition. To quote Mark Fisher: “Capital is an abstract parasite, an insatiable vampire and zombie maker; but the living flesh it converts into dead labor is ours, and the zombies it makes are us.”

Matteo Bittanti: The cyber-king protagonist of your latest video work descends into narcissism, megalomania, and addiction to personalized attention. Do you see this phenomenon as a broader commentary on how online media impacts individuals’ perceptions? Are video games used here as a metaphor for the gamification of communication and performance in the dying age (hopefully) of social media? Is a technology-dominated existence a doomed existence?

Babak Ahteshamipour: From the way I perceive the situation, I would say yes. This phenomenon has been a topic of research and criticism for a long time now. It has been said that social media affects an individual's brain, like having a short attention span. From my viewpoint there is a connection between media and accelerationism, everything is running at high speed, antagonism, profit and technocracy is accelerating at unimaginable speed. The rapid development of AI, the normalization of war, the funding of the arms industry, and the polarization, wokeness, cancel culture and identity politics predominating on social media are a few examples of this. Individuals feel a pressure to be quick learners, have opinions faster, take detours to acquire knowledge in haste, as if a reaper is hunting them. The use of gaming to approach this topic references Alexander R. Galloway’s viewpoint Gaming: Essays on Algorithmic Culture: that underlines how gaming is action-based. “Short attention spans, cultural fragmentation, the speeding up of life, identifying change in every nook and cranny — these are neuroses in the imagination of the doctor, not the life of the patient” are part of gaming and digital generation, as he writes. While playing games you are in constant adrenaline, aware and focused. When will the next zombie appear? What obstacle to dodge next? What spell to cast to survive? Where should I position my avatar? There is a conversation between the operator and the machine. RL has been gamified as well, something I point out in my essay Misplaced and displaced… There is a vampirism to it, being aware when the next scandal comes out of the fog, who will be next canceled, which corporation will be blamed for feud and the destruction of a biome or in which new commodified polarization one has to attend online.

Matteo Bittanti: In your latest video work, you depict the downfall of a cyber-king/edgelord figure as a way to challenge the predominance of hero-centric, patriarchal narratives in gaming. His downfall is therefore meant as a gesture that undermines traditional power dynamics in digital games. I’m curious whether you see the downfall of this kingly figure as actively subverting the traditional power dynamics reinforced by many popular games, or if it functions more as wishful thinking or fantasy in a market that still tends to reward continuity over progress when it comes to narrative tropes. More broadly, do you think the aesthetics and storytelling of mainstream games are shifting substantially to undermine hero-driven ideologies, or does big structural change still feel largely aspirational at this point?

Babak Ahteshamipour: Games are trying to do better in this area actually, introducing more inclusivity, gender-fluid characters, free roaming camera modes, much more cultivated storylines that showcase the complexities of the relationships between characters, terrains and truths. Of course there are some ingredients such as heroism, violence and machismo that stay intact. White heterosexual men still dominate gaming communities. An interesting example of this is in Overwatch studied by Tanja Välisalo and Maria Ruotsalainen in “Sexuality does not belong to the game” — Discourses in Overwatch Community and the Privilege of Belonging” where the two queer characters Tracer and Soldier: 76 were received both positively and negatively by the community, but mostly negatively. Although video games have always had a conversation with queer theory, as noted by Bo Ruberg in Video Games Have Always Been Queer: “Queerness and video games share a common ethos: the longing to imagine alternative ways of being and to make space within structures of power for resistance through play.” This longing for alternatives within video games is specified by Nick Dyer-Witheford and Greig de Peuter in Games of Empire: Global Capitalism and Video Games as well: how modding and corrupting, machinima, counter-gaming, roleplaying and in-game communities provide growth and space for the multitude, which according to Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri consists of singular and unique social subjects that cannot be reduced to just entities enslaved to bare survival.

Matteo Bittanti: What role does music production play in your practice? Is it the fulcrum, the catalyst, the point of departure, or just one of the mediums you employ? How do you approach the tension between the aural and the visual? What comes first, the sound or the image?

Babak Ahteshamipour: Music production plays a major role in my practice since I am a musician and I got involved in visual art because I was fascinated by video clips and album covers. I don’t always employ music in my works but music always plays in the background during work. When it comes to order, it’s random, sometimes the visuals come first and then the music or vice versa. For Hey Plastic God… the music came first and then the clip. The texts play a role as well, they are always written separately and at different occasions, mostly when I am experiencing desperation, anxiety, anger and sadness. When I’ve finished a piece and want to add text to it, I will just go through my writings and see what seems suitable.

Matteo Bittanti: In both Hey Plastic God… and Post-Coded Thoughts…, you appropriate and remix elements from classic video games like Super Mario 64 and The Sims to construct surreal, psychologically charged spaces. Specifically, you insert darker dreamlike paintings into the familiar 3D environments. Can you walk me through your artistic process for hijacking and repurposing these game worlds? How do you go about selecting specific structures, angles, and snippets of gameplay, images, characters, tropes to disrupt?

Babak Ahteshamipour: The reason I’ve chosen to hijack these games firstly was that I played them as a kid and have nostalgic attachment with them. Secondly they have some discourses inherited in them that I have my head wrapped around as well, such as the hyper-capitalist consumerism culture in The Sims or the helpless female waiting for the hero to come and save her in Super Mario. For Post-coded Thoughts… I started by designing and decorating a house that I liked, making myself, importing my paintings and music and then just recording the avatar doing what I’d do in my everyday life. It took me a lot of shots to get what I wanted. I also made a life for him so that I’d enjoy the process and feel connected to him. I could actually live the life he did live!

For Hey Plastic God… I dug into archives of ripped game models, found some that I liked from Super Mario 64 and its remastered version Super Mario 64 DS, decided which paintings would make sense to be positioned and at which spaces. Then I started creating the 3D models of the paintings, imported them into the spaces, animated them and rendered them. After rendering or shooting, post-production starts with putting the footage together, doing a bit of color correction, adding some effects, the text and the music above it. Eventually it’s putting pieces of the puzzle together, things always change during creation, there is a vague idea that is coming into life through extended improvisations.

Matteo Bittanti: I’m also curious about what draws you to working with games like Mario and The Sims as source material. They both have an air of zany playfulness on the surface that you seem to delight in warping and distorting. Is it partly the contrast between the cheerful appearances and deeper anxieties that makes them appealing canvases and video art? More broadly, do you feel a sense of nostalgia for these games from your childhood, or are they primarily useful as cultural symbols and tools to remix? Hey Plastic God also appropriates LEGO and toy soldiers, highlighting the more sinister themes embedded in children’s toys, which I also consider pervasive and unsettling.

Babak Ahteshamipour: Well, all the above! I felt nostalgic towards these games. A lot of my friends they’ve also noticed that the games I choose to implement in my art have a lot of similarities to my aesthetics, so I guess unconsciously their elements and visual appearances have penetrated into my work. It’s interesting that you mention LEGO and toy soldiers. A notion I am interested in is that of play. Play can be a universal language that all species use to become intimate, friendly, gain trust and deal with anxiety. From my viewpoint, playing deterritorializes symbolics structures, norms and history, in an attempt to reterritorialize them, forge new connections, discover new perspectives, reconsider narratives and resolve tensions as Derrida stressed out in Structure, Sign and Play. “Playing is itself Therapy” Winnicott pointed out, while playing one enters a twilight zone outside of space-time where enjoyment, curiosity, thoughtfulness and engagement take place. War, militarization and colonial narratives, sexism, racism and other obscure, violent, disturbing and brutal themes have been commodified and normalized into innocent and playful toys that happen in the imaginary realm of play. The same goes for video games as discussed and underlined in Games of Empire: how racial capitalism has been normalized in games such GTA, how war has been banalized in games such as Full Spectrum Warrior and Call of Duty and how U.S.A.’s military has been deeply entangled with creation of video games besides the famous example of America’s Army, which aimed to recruit individuals in the army. U.S.A.’s military has now moved on to the gamified reality by recruiting e-girls to promote militarization through hypersexualized Otaku inspired cosplays, something punctuated by Günseli Yalcinkaya in “How E-girl influencers are trying to get Gen Z into the military”. Play provides opportunities for alternatives to appear, a hope against capitalism realism that oftentimes gets degraded into a commodity and reappropriated for advertisement.

Matteo Bittanti: Both the album Specter, Spectrum, Speculum and your video Hey Plastic God… are described as critiquing the narcissism and “power fantasies” enabled by digital culture and gaming. How do you see your music and visuals acting as a “cautionary tale” about the mental health impacts of digital addiction (and pharmaceutical addiction) and delusions of grandeur?

Babak Ahteshamipour: My works never intend to be pedagogical, rather than food for thought. They are purely self-explanatory and just an expression of my own fears, anxieties and obsessions. As far as I can tell this particular piece would not prevent anyone from becoming addicted to any sort of digital or pharmaceutical addiction but I don’t promote the contrary either.

Matteo Bittanti: What’s next for you?

Babak Ahteshamipour: Right now I’m working on the artwork of my third album, which is to be released in 2024, along with three video clips for three tracks of the album and a possible virtual world. Additionally, I am slowly developing other ideas such as an essay about normalization of animal cruelty, commodification of digital bodies and extractivist activities in video games. There’s also a curatorial project that I’ve had my head wrapped around which is about virtual vs RL forests inspired by dungeons & dragons rituals and black metal theory. It aims to critique the institutional and commercial demand for hyper-realistic video games and digital art, that eliminates spiritual and fun aspects of artistic practices and creations. Lastly I am planning to remaster In Search of the Banned Dictionaries…

Hey Plastic God please don’t save the Robotic King

single-channel digital video, color, sound 5’ 33”, 2023, Iran/Greece

Created by Babak Ahteshamipour

Courtesy of Babak Ahteshamipour