KINGDOM OF SHADOWS

Recording of live animation performance, sound, color, 11’ 20”, 2021, Israel

Created by Amir Yatziv

Actors: Neta Shpigelman, Eliya Tsuchida

Computer graphics: Yuliya Bogonos

Courtesy of the Artist and Galleria Laveronica

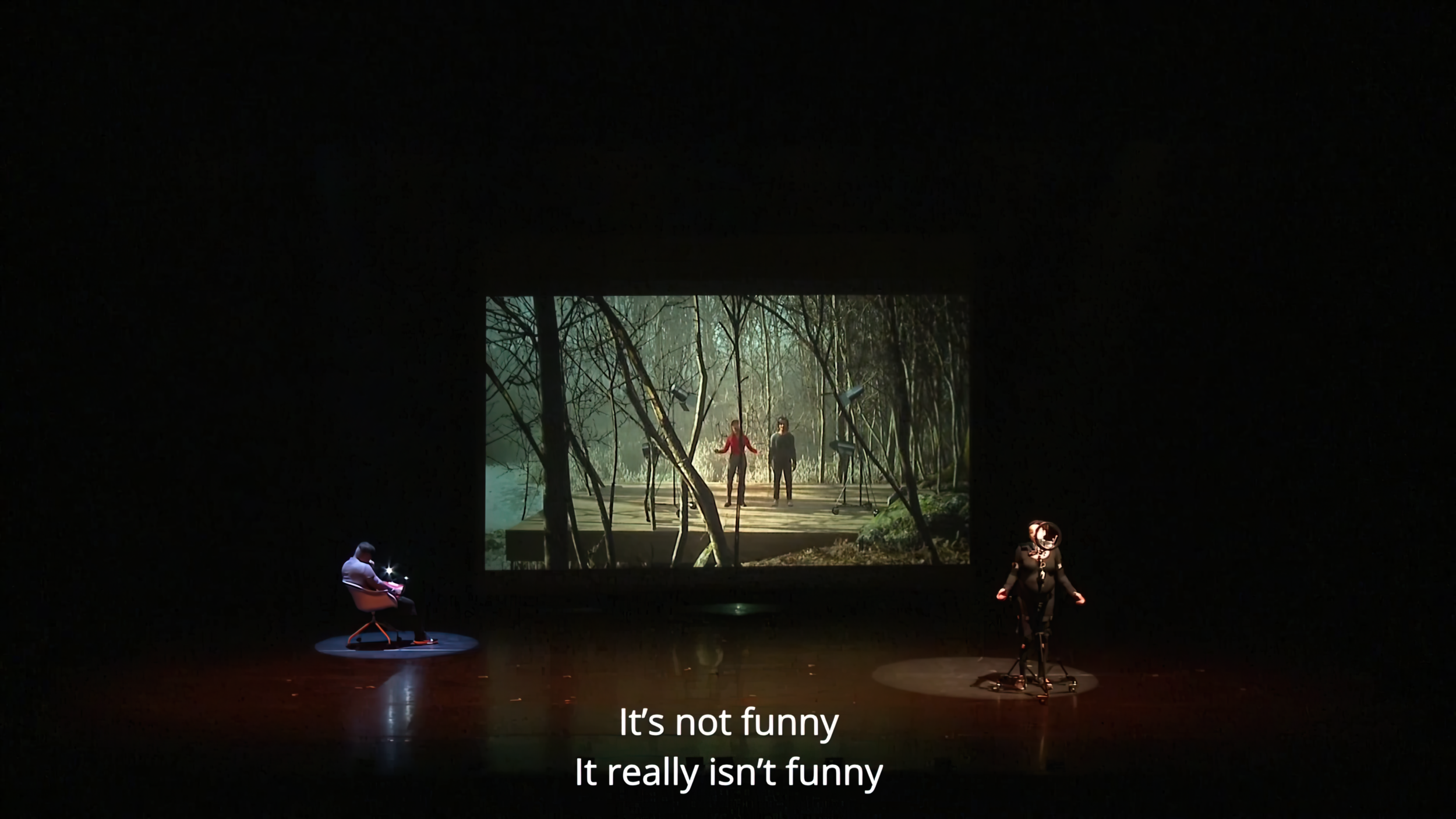

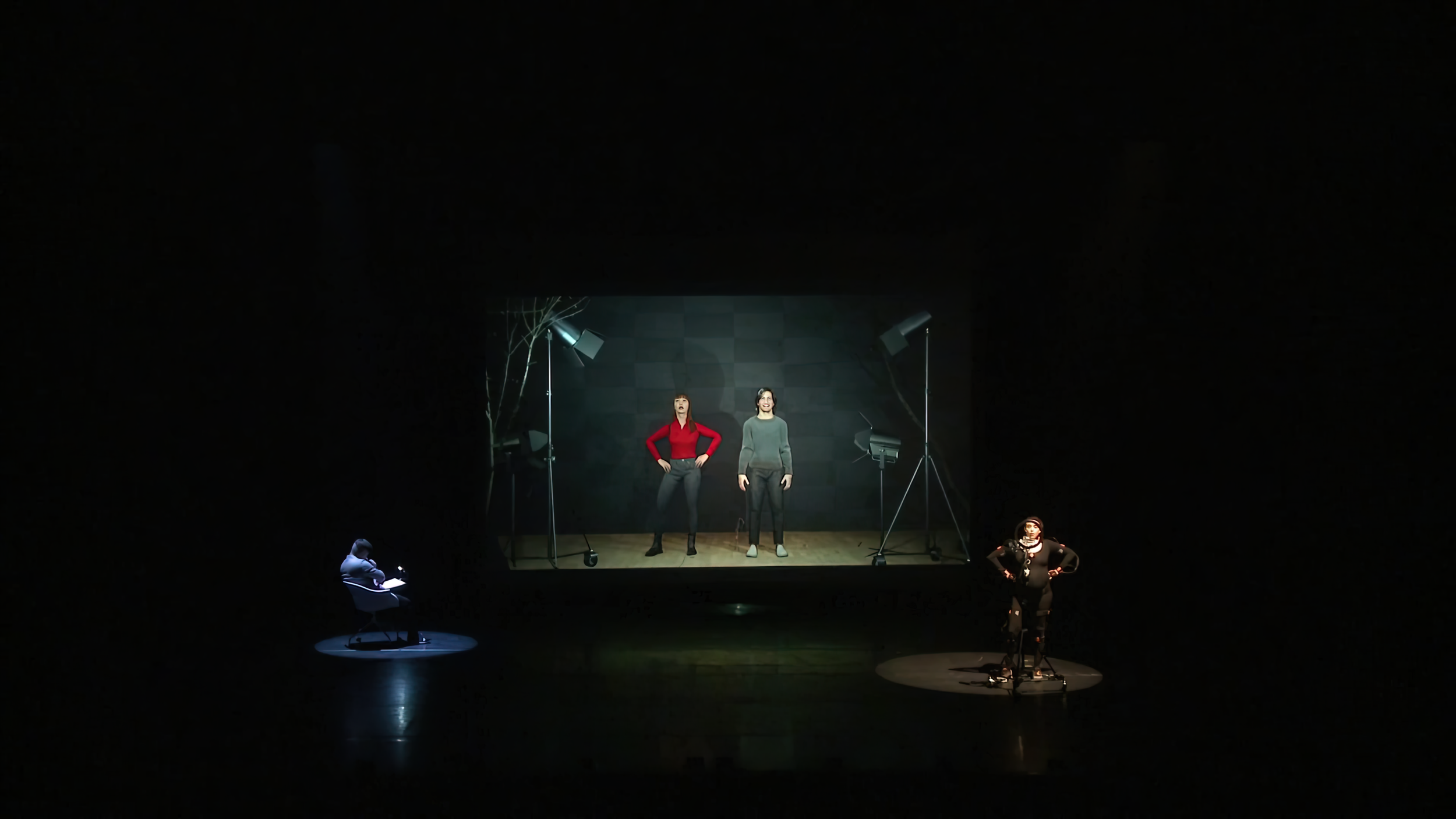

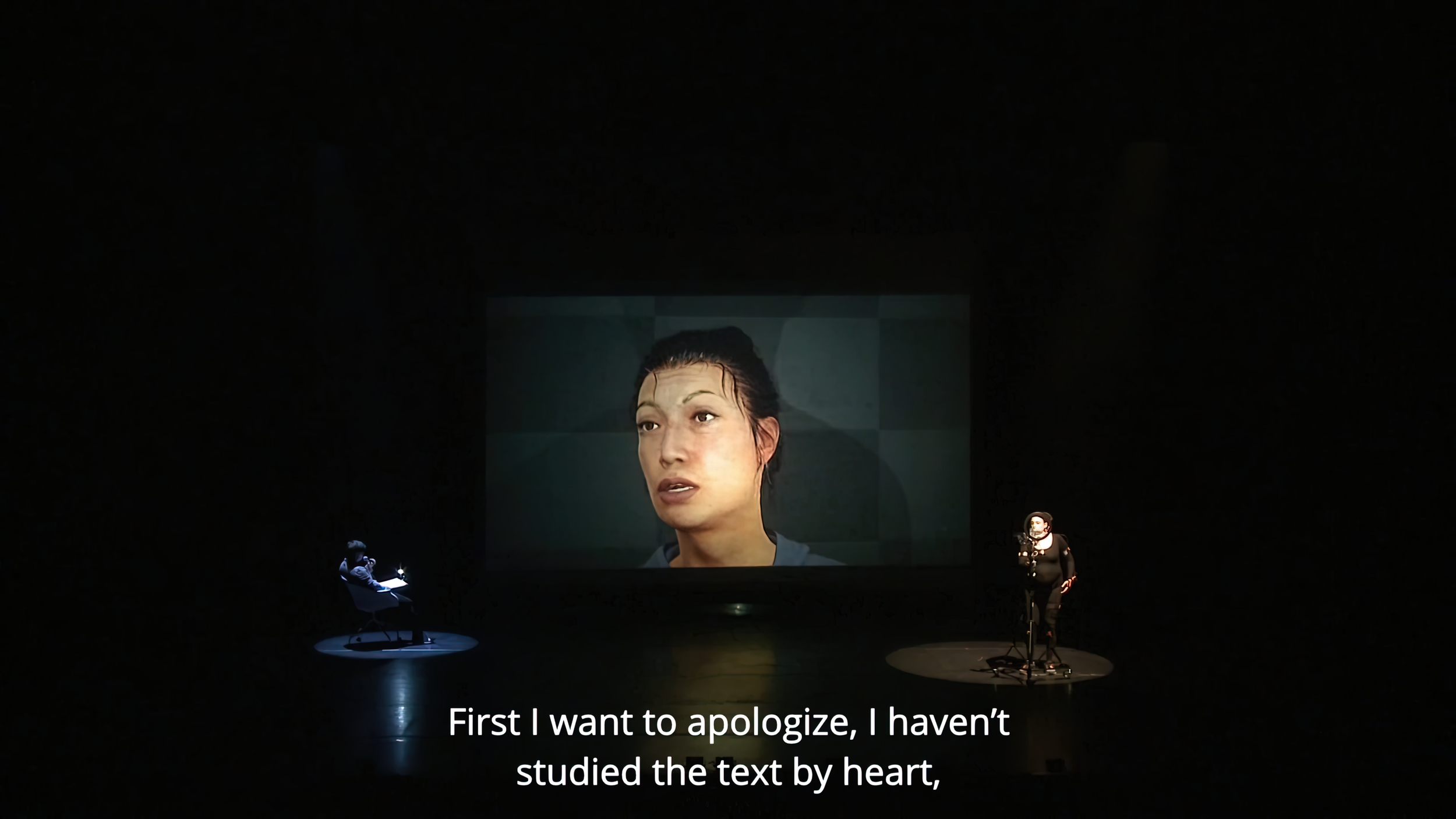

Three avatars are auditioning for the role of a video game character under the vigilant eyes of a Japanese game designer. A human actor, wearing a motion-capture suit, executes a set of actions in real life that are simultaneously performed by her virtual counterpart on a giant screen. Spectators see both. Conceived and produced by Amir Yatziv, this live performance blurs the lines that traditionally separate theater from digital gaming and invites viewers to consider the porosity between reality and simulation. Inspired by the romantic encounter of two characters in an episode of Final Fantasy, Kingdom of Shadows investigates changing notions of identity, performance, and communication in a screen-based world.

Born in Israel, Amir Yatziv lives and works in Tel Aviv. After receiving a B.A. in Computer Science at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya in Israel, he studied Arts at the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. He directed several short films which were often exhibited as art installations as well. Among his solo exhibitions are This is Jerusalem Mr. Pasolini, Petah Tikva Museum of Art, Israel (2013), This is Jerusalem Mr. Pasolini, Galleria Laveronica, Modica, Italy (2012), Antipodes, Ramat-Gan Museum of Art, Tel-Aviv (2010). Group exhibitions include Too early, too late. Middle east and modernity, curated by Marco Scotini, Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna (2015), Space Oddity, A capsule exhibition, Kunstverein Nürnberg, Germany (2014), La guerra che verrà non è la prima, 1914-2014, MaRT, Rovereto (2014), Recalculating Route, 4 Mediations Biennale, Poznan (2014), CounterIntelligence, Hart House, curated by Charles Stankievech, University of Toronto, Canada (2014), Time Pieces, Nordstern Videokunstzentrum, curated by Marius Babias and Kathrin Becker, Gelsenkirchen, Germany (2014), Measure for Measure, curated by Drorit gur-arie and Hila Cohen-Schneiderman, Petah Tikva Museum of Art, Israel (2014), Give Us The Future, curated by Frank Wagner, n.b.k Berlin, Germany (2014), Artists’ Film International, Whitechapel Gallery, London, United Kingdom (2014), Multiplicity, NURTUREart, curated by Marco Antonini and Hila Cohen- Schneiderman, New York (2014).

Matteo Bittanti: You studied computer science at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya in Israel and subsequently joined the Bezalel Academy of Arts and Design in Jerusalem. This makes you a member of a relatively small – but growing – cadre of artists who can also code. In several ways, you represent the prototypical Renaissance man who can overcome what C.P. Snow called the “two cultures” schism. You also fully grasp the idiosyncrasies of linear fiction, such as cinema, as well as those of interactive fiction. For instance, in 2017, you directed Another Planet, an animated documentary about the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp and created a live simulation called The Fox and the Crow. The former is a scripted, self-contained narrative whereas the latter is an endless, generative work that, by definition, exceeds the ability of the viewer to fully experience it, that is, from beginning to end. Formally, they could not be more different. I am very interested in their underlying logic. What were your original intentions in creating Another Planet and The Fox and the Crow? Could you imagine developing a live simulation based on Another Planet or a “closed” narrative based on The Fox and the Crow or the very nature of these artworks makes such an endeavor futile? In your practice, is the medium also the message, to paraphrase McLuhan?

Amir Yatziv: In both cases, I chose a medium which allowed me to better develop the original concept or answer the questions that I was trying to ask with the artwork, with the content or with the narrative. Another Planet was originally conceived as a meeting of... An interview, let’s say... Better yet, a documentary based on a series of interviews with different people, all connected by a single thread: they were trying to recreate the Auschwitz concentration camp in a 3D environment, as a 3D application. Although their motivations differed in nature, they were all equally interested in creating a virtual replica of Auschwitz. Thus, my original project – making a documentary about these six individuals – was preserved in the sense that instead of interviewing them in their office, home or elsewhere, I decided to put them into the virtual concentration camp they developed. So I literally asked them for the code or for the open source version of their simulation. Then, when I went back to my studio, I opened the application, that is, the same virtual camp. I inserted and subsequently staged their avatars, dubbed the interview, and produced the full documentary. As for the second project that you mentioned, The Fox and the Crow, obviously, it is not based on an historical event, but it’s a fairy tale rich in metaphorical content. Basically it’s a children’s story, but I was not really interested in making a traditional adaptation, so to speak. Instead, I wanted to give it a new kind of interpretation, by using the medium of live simulation. This basically means that this artwork is driven by an artificial intelligent engine which continuously generates new situations. So, unlike the original children’s story, you never know how this version is going to end, how long it is going to take, and what it will eventually look like. That’s the reason why I chose a live simulation for that children’s story.

Matteo Bittanti: In this exhibition we are presenting Kingdom of Shadows, i.e., a recording of a performance created with a live simulation engine that was originally attended by a live audience. As a curator and media scholar, I am very interested in reception theory. Do you believe that the display mode of an artwork is somehow prescribed in/by the artwork itself – and thus by the artist – meaning that a work meant for screening could not be shown as a video installation without betraying its original intent, or do you believe that the artwork’s meaning is relatively fluid and adaptable? If so, how does the context in which a work is experienced influence, or even alter, the artwork’s content?

Amir Yatziv: Kingdom of Shadows was originally created for a live performance on stage. The main motivation behind the project was the idea of creating an avatar, which is a character controlled in real time by a human being on stage. Obviously, the only way to show this process was to stage a live performance, because, in this example, the medium I used – that is, live performance – is mixed with the screening of the avatar. So, you could say that the medium of Kingdom of Shadows is part of its message, part of the content... Kingdom of Shadows is trying to ask questions about the nature, the soul of this character. Is it human? Is it a human being? An avatar? Or something in between? In other words, with this work I was posing a series of questions about the gap that separates machines from human beings. I was also trying to create some kind of hybrid creature, a cyborg. To achieve such a goal, I could not but use the medium of live performance, having an actor on stage performing as an avatar.

Matteo Bittanti: Within the field of game studies – the academic discipline that investigates video games – there’s a vibrant tradition that connects digital gaming to puppetry rather than cinema or other media. Some scholars like Michael Nitsche and Mary Flanagan for instance argue that the performative aspect of digital play – which involves a player using a controller or body movements to control a virtual alter ego which becomes an extension of themselves – makes manifest the fact that, as an activity, video game playing is all but a remediated, updated version of doll play or, indeed, puppetry. In Kingdom of Shadows the performative aspect of play, hereby understood both as a ludic activity and acting, plays a key role, no pun intended. How did the project come into being? What came first, the technology or an intent, a desire to question the very notion of performance?

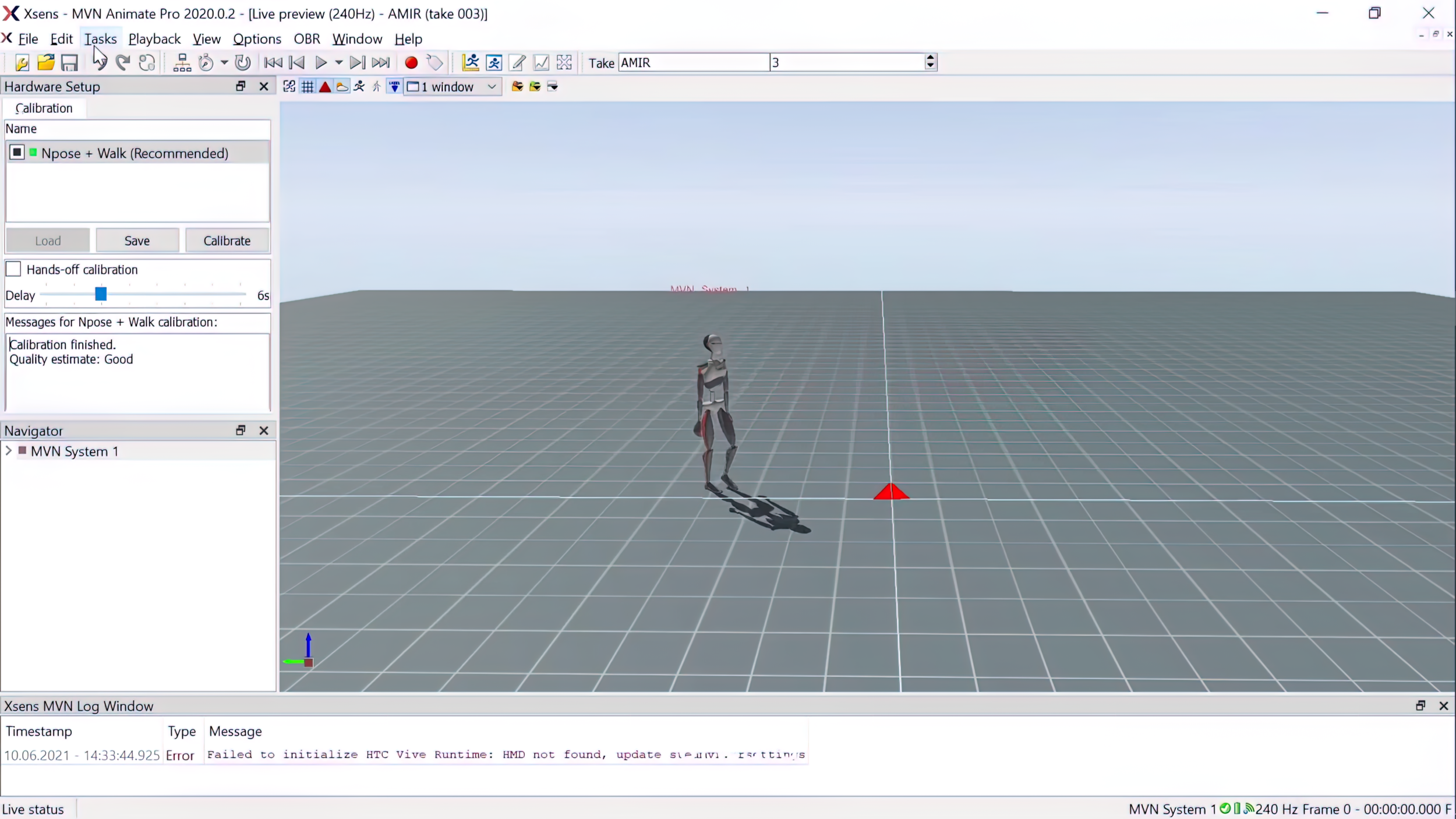

Amir Yatziv: Kingdom of Shadows originally began with the technology itself. Obviously, I was fascinated by the opportunity of creating an alter ego and controlling it in real life and on stage. But unlike gaming, I was much more interested in connecting these two poles, not the gamer but rather an actor from theater, a classically trained actor so to speak. Basically, I was very interested in the controller. So, to investigate the relationship between an actor who is trying to become a different character and the avatar itself, we were trying various ways to control it, to simulate realistic, convincing facial expressions. I was interested in finding the limits of an artist’s expression. I was interested in making him feel something, like sadness or happiness. In short, the fundamentals of acting, which were very complicated for the human actor we worked with. This, in short, is the process that we followed for this project. The idea is that this actor is coming in for an audition and we watch her perform and act as an avatar on stage.

Matteo Bittanti: Several scholars argue that the quintessential quid of digital gaming, is interactivity. However, it seems to me that what makes them so different, so fresh, so appealing is iteration. In other words, video games constantly change both at a diegetic level – as the actions performed by the player allow for some kind of emergent gameplay, that is, unscripted situations and unexpected outcomes – but also at a technical level, as the very code of games is constantly updated, revised, and implemented through patches, fixes as so on. In a sense, games “improve” or at least “change” over time, unlike other media, like film and literature. In regard to Kingdom of Shadows, how do you plan to present this specific artwork over time? Will it evolve and iterate, like code itself? Is this project akin to a generative matrix that can churn out several different narratives or fictional situations? In short, is Kingdom of Shadows many different kingdoms? The performance at Artport Tel Aviv, for instance, features both a prologue about automation and a coda with a singing performer, book ending the audition in a very interesting way...

Amir Yatziv: This is a good question. Kingdom of Shadows is many different shadows, in the sense that we show different iterations each time. As of now we had two different shows and I guess that the next one will also be a bit different as well. I felt that the show had to be a little bit different because we are literally playing with a medium, gaming, which can reinvent itself every time you experience it, in the sense that not all your actions are scripted, ple-planned as you were saying. So, in that regard, I think that each show will differ slightly from its predecessors. We’ll introduce different segments in the new versions, organically.

Matteo Bittanti: The notion of performativity is strictly connected to identity and gender, as Judith Butler has cogently argued. Erving Goffman, on the other hand, stressed that we all perform a version of ourselves for all kinds of audiences – including for our own selves, as one of the characters auditioning for the part seems to allude when she refers to “smiling as therapy”. In other words, we are always performing even when we are alone. What does digital technology, especially gaming technology, add to this already complex nexus of endless performance?

Amir Yatziv: To answer this question I must provide some contextual information. I should clarify that the game we chose for the project was Final Fantasy X. When I was researching this game, I found out that one of the most interesting features was a love story between the characters. That’s when I had this idea of recreating a scene from this specific game, and thus re-enacting the romance. There’s a love story between a young man and a young woman, and we are recreating this specific scene in the audition. We are doing a part of the scene where she’s explaining how to smile, how to reproduce the original smile. I think this is where the gaming component came into being, that is, where the gaming technology or gaming medium came into the performance. I don’t know if I answered your question, perhaps it’s a different way of looking at it.

Matteo Bittanti: Digital play and video games recur in several of your artworks both as themes and as tech. In a sense, this fascination for playful media operates like a connective tissue. What is your relationship to video games? Why do they occupy such a prominent space in your practice?

Amir Yatziv: I have never been a “real gamer”. I never played a lot of video games, but I have always been fascinated by the opportunity to simulate and to encounter different moments inside games. I remember that when playing a game, I was interested in the idle moments between intense action. So let’s say that you are fighting a character and then it’s over and afterwards there are a few seconds in which nothing happens. You know, the trenches of the trees are still being moved by the wind in the distance, the characters are waiting and breathing heavily because the idling routine suddenly kicks in… So there are these few seconds after an intense section of the game where nothing special happens. And I was fascinated by these idle moments for reasons that I cannot rationally explain. But I think that this is why and when gaming entered my artistic practice. I think it allowed me to observe a different world, in a delicate, subtle way. A wonderful way of questioning the rules that inform that particular world.

Matteo Bittanti: Another recurring theme in your oeuvre is the idea that history is a narrative that gets continuously updated, rewritten, expanded, amended, and erased. Thus, the notion of historical truth is, at best, an oxymoron. In many ways, Kingdom of Shadows is a reminder that we are still stuck in Plato’s cave: our narratives are literally determined by the media – or the contingent situation – that define our condition. Susan Sontag used Plato’s fable to describe an epistemology based on the photographic in On Photography (1977). You evoke the notion of shadows to address a world in which video games – both as a technological ecosystem and metaphors – proliferate. Is there something intrinsic to digital gaming that makes your “cave” different from Plato’s – and Sontag’s?

Amir Yatziv: Actually, I was not thinking of Plato’s Cave at all. Perhaps it’s helpful if I explain where the title of this work came from. So the origins can be traced back to a text written by Maxim Gorky around 1896, shortly after the “invention” of cinema... Gorky, the Russian writer went to the movies for the first time in his life. He was fascinated by the new medium and wrote an article for a newspaper, titled [Last night I was in] “The Kingdom of Shadows”. But he was somehow disappointed that the movies he saw were silent – in fact they would not have a proper soundtrack for thirty more years or so – and spectators could only see black and white images projected onto a screen. Gorky called these projections “the kingdom of shadows”. He thought that cinema was disappointing when compared to the art forms of his age, like theater, and other media. I decided to name my artwork after Gorky’s article because I see it as a new medium, this kind of live performance of avatars onstage. That’s the reason the shadows came into the title.

Matteo Bittanti: In a sense, an audition is structured like a game, because there are rules to follow, competing goals among all parties involved, and clear outcomes: the candidate can either get (“win”) the part, or not (“lose”). Although the conversation makes clear where the power resides – the director, Eliya Tsuchida, is in control, while the performer, Neta Shpigelman, is being evaluated –, the exchange is illuminating insofar as it brings to the foreground a sense of alienation and frustration in all the characters. I was wondering if Kingdom of Shadows could be also understood as a commentary on the many pitfalls of language, on the gap between communicating and understanding – matters of coding and decoding as Stuart Hall would put it – an issue that machines and algorithms not only have not been able to address yet but, in many cases, made even worse...

Amir Yatziv: I think Kingdom of Shadows is also about translation. Throughout the performance, we witness a constant conversion from one language into another. I deliberately decided that the director, Eliya Tsuchida, would only speak Japanese while the actor, Neta Shpigelman, would only respond in Hebrew. There are subtitles on screen, live, which makes the whole experience a bit weird, since subtitles are usually a feature of cinema, they are common to the “offline image” rather than to real time events, live performances, something we know from theater. Anyway, I think all of these elements, languages, and live subtitles highlight the complexity of the translation: viewers understand that they are witnessing a communicative process that they do not fully understand. How is it possible that the director speaks Japanese and she answers in Hebrew? I think that this choice alludes to the task of converting data from one context to another.

Matteo Bittanti: Kingdom of Shadows reminded me of Pirandello’s plays about the plight of the cinematic actor, who laments that the camera is producing alienating effects. In his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Technical Reproducibility”, Walter Benjamin quotes Pirandello to illustrate the difference between the auratic, situated, in situ acting of theatrical actor and the machinic/mechanic acting required by cinema. How would you define the “acting” of the avatar within a video game/simulation? Is it the ultimate form of alienation?

Amir Yatziv: To me, the live performance indicates that the avatar, which is an agent controlled by a human being, is embodying the best of the human and the best of the machine. This is something new for me, but I look at this work as an experiment. What I am trying to do is to combine the strengths of these two agents, the machine and the human being.

Matteo Bittanti: We live in a world where socially distanced interactions are becoming more common. The proliferation of viruses and climate change render physical traveling more of a burden on an environment which is already on the brink of systemic collapse. The schizophrenic nature of video game performance – i.e. one subject playing multiple avatars – is bound to become more common as Big Tech billionaires such as Mark Zuckerberg try to sell the “metaverse” to the masses. In this sense, Kingdom of Shadows seems a prefiguration of things to come. What role does art play in a world where the screen has become the de facto standard interface to access any kind of “content”?

Amir Yatziv: I think that in my work, I’m not really going into that direction, but I rather make a comment on that imagined metaverse where multiple characters can become one person, because I think that, ultimately, it is somehow a failure in my piece, there is kind of a leak between the virtual and the reality. The leak is the love story, which was in the past, maybe between the actor and the director, something that cannot be in a real world, but something happened there that broke the system, of the boundaries, the veil of the virtual and the real, there was something there that disrupted the scene because there was something between the character and the human being. And maybe that’s in a way I comment on that, or maybe it’s a critical point of view on that future that you mention.

Matteo Bittanti: Multiple characters converging into one person… This reminds me of Being John Malkovich, the ultimate video game movie... Speaking of games, motion-capture suits are very common in game development and movie production these days. By making visible the invisible, and yet embodied relationship between the “puppet master” and the avatar, you simultaneously nullify the uncanny valley effect of the simulation and stress its significance in constructing the “reality effect” that allows viewers to willingly suspend their disbelief and immerse themselves into the fantasy. Do you believe that the massive popularity of video games is inherently connected to their ability to photorealistically reproduce “reality”? Or is their artificiality inevitably manifested in the form of glitches or weird animations, for instance in the Airport Tel Aviv prologue, when the speaker repeatedly turns his head and his face looks distorted?

Amir Yatziv: I’m not sure that photorealism is what makes video games so popular. Rather, I think that the virtual space is calling for surprises. It’s calling for an interruption, it’s calling for glitches, and you are in some kind of different state than in reality. And I think that’s what attracts us when we immerse ourselves into a virtual space or a virtual environment. We experience situations that are so different from those that we encounter in reality. And that’s why gaming opens our mind in different ways. It’s calling for a different way of thinking, it opens up a different state when we are in this zone.

Matteo Bittanti: A central theme of Kingdom of Shadows is the idea of translation, or rather, mediation, which is a crucial concern of media philosophers such as Vilém Flusser and Friedrich Kittler, but also of artists such as Harun Farocki and Hito Steyerl. As you write, “using a motion-capture suit, the movements of the human actor are translated into those of the on-screen image, which for the spectators actually represents the ‘real’ actor, much like a digital text of ones and zeroes is commonly perceived as the representation rather than the origin of the moving computer image.” This epistemological confusion – our inability to comprehend the very nature of what Flusser calls “the technical image” – is so common that we must rely on works of art to be reminded of its profound effects. Do you believe that the highest purpose of art is pedagogical – that is, its ability to reveal something about the world that we have not properly understood or perhaps forgotten – or is that assessment too didascalic?

Amir Yatziv: I’m not sure if what you mention is the ultimate purpose of art. I think art is above all about asking questions. The artist asks questions. The viewers ask questions as they experience the artwork or after seeing it. At least, that’s the purpose of my artistic practice.

A CLOSER LOOK AT KINGDOM OF SHADOWS

KINGDOM OF SHADOWS

Recording of live animation performance, sound, color, 11’ 20”, 2021 (Israel)

Created by Amir Yatziv, 2021

Courtesy of Amir Yatziv and Galleria Laveronica, 2021

Actors: Neta Shpigelman, Eliya Tsuchida

Computer graphics: Yuliya Bogonos