PHIL RICE

THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE AI

MARCH 21-27 2022/21-27 MARZO 2022 (ONLINE)

Interview by/Intervista di Luca Miranda

OBIT

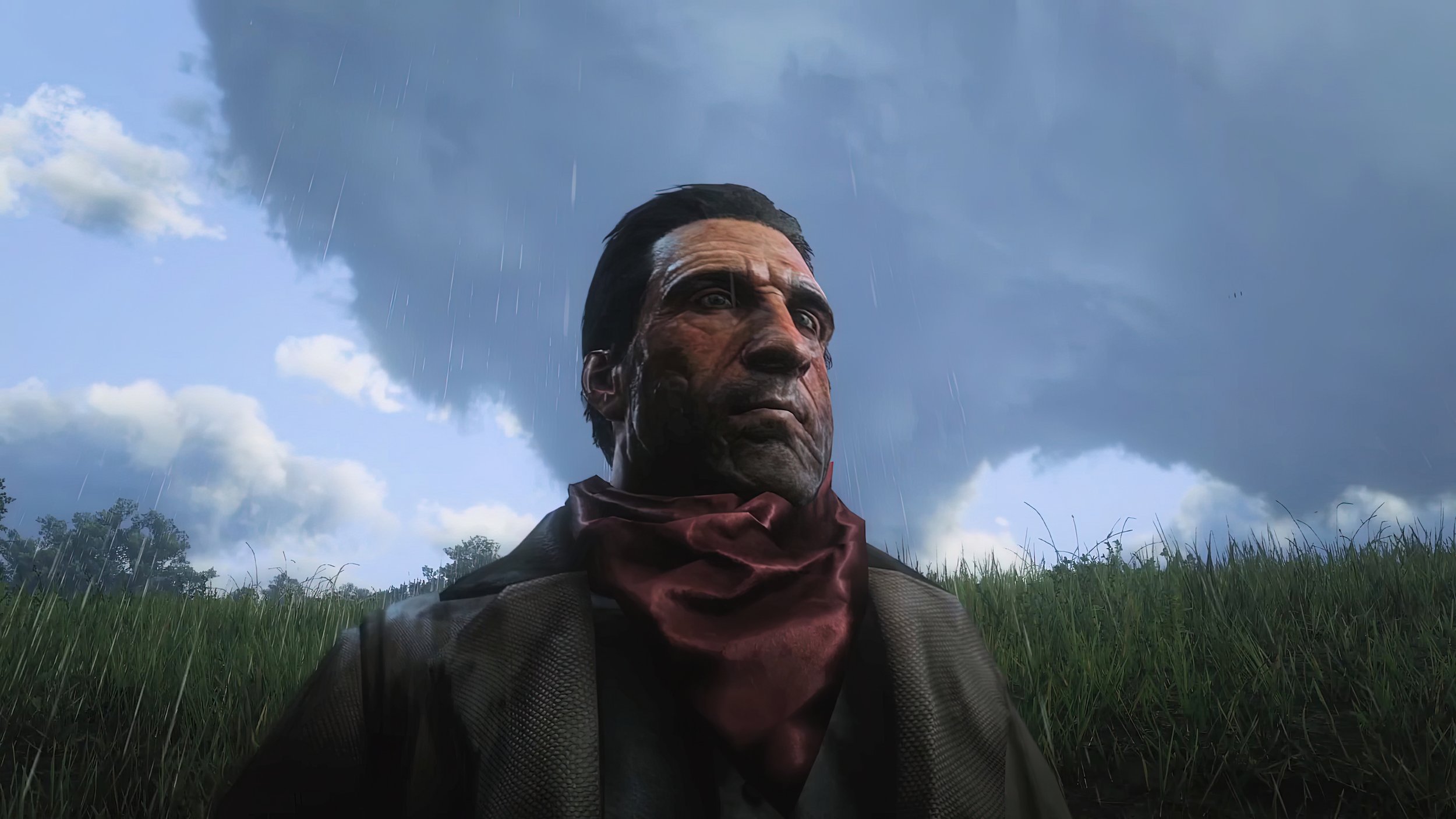

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 13’ 41”, 2021, United States

Creato con/in Red Dead Redemption 2, Obit racconta la storia di un solitario cowboy in viaggio verso casa con il suo fedele cavallo, per dire addio. Tuttavia, giunto a destinazione, le cose non vanno come previsto…

Created with/in Red Dead Redemption 2, Obit tells the story of a lonely cowboy who travels home on his trusted horse, to say the last goodbye. However, things don’t go as expected as he reaches his destination.

L’ARTISTA

THE ARTIST

Phil Rice è un regista di lunga data specializzato nella produzione di film digitali grazie all’appropriazione e modifica dei videogiochi. Tra il 1998 e oggi, Phil ha prodotto circa cinquanta cortometraggi in una varietà di generi e con diversi strumenti. Inoltre, ha curato il sound design e il soundtrack di numerosi progetti. Le sue opere sono state presentate a festival cinematografici e mostre internazionali. Tra i lavori più noti di Phil spicca Male Restroom Etiquette, uno dei machinima più visti di tutti i tempi. Male Restroom Etiquette è stato usato come ausilio didattico nelle classi di psicologia delle università di tutto il mondo, è citato dal Guinness World Records, ed è stato proiettato in oltre venti festival cinematografici in dieci paesi. Phil cura un popolare podcast sul machinima, e fa parte di uno studio di gaming/modding chiamata CalusaMC e dello studio musicale Mad Hominem. Vive e lavora a Estero, in Florida.

Phil Rice is a veteran machinima artist who creates digital movies by appropriating, repurposing, and modifying video games. Between 1998 and the present, Phil has produced approximately fifty short films in a variety of genres and with multiple tools. Additionally, he has done sound design and musical score for dozens more. His work has been featured at international film festivals and exhibitions. Among Phil’s best known works is Male Restroom Etiquette, one of the most watched machinima of all time. Male Restroom Etiquette has been used as an instructional aid in college Psychology classrooms around the globe, earned an entry in the Guinness World Records, and has been featured in over twenty film and animation retrospectives in ten countries. Phil is the host of a popular machinima podcast and is part of gaming/modding venture CalusaMC. He is also a singer/songwriter for Mad Hominem. He lives and works in Estero, Florida.

INTERVIEW

Luca Miranda: You began experimenting with machinima in 1998, when ‘machinima’ was not even a word. You’ve seen this medium or format or genre evolve and change throughout the years. What is machinima to you, today? Do you feel that machinima’s potential as an art form has been fulfilled? If not, what’s missing? How do you explain the extreme popularity of photo modes within video games vs. the relative paucity of movie/machinima editors in recent triple A productions?

Phil Rice: Good grief, what a question! (laughing)

We can’t talk about machinima without acknowledging it as a cultural phenomenon. Machinima first emerged out of a community of artists, writers, hackers/modders, and programmers who all happened to play certain types of video games, and saw a potential for artistic expression and/or social commentary using the platform of those games. And for the most part, that is still the heart of machinima today. Sure, the fact that many games today include built-in filmmaking tools has helped lower the barrier for entry into the craft, but the best machinima work still ultimately relies upon someone altering the game to make it do something it wasn’t designed to do.

For me, the draw has always been a pragmatic one. Machinima’s big appeal, from a production standpoint, has always been speed... or more precisely, ease. Machinima enables one, generally speaking, to get more done – and faster - than conventional filmmaking and certainly conventional 3D animation techniques, with less personnel, and with less cost. That doesn’t mean it’s not difficult, by any means. But relatively speaking, it’s just faster. Because of the real-time element of the animation rendering, because of the ability to leverage the work (game content) of professional graphic artists, character designers, and world builders.

Why is ease important? Well, for one, our time as humans is finite. The less time it takes to produce something, the more of that thing we can make. Same goes for the financial elements... our budgets are finite. Suddenly, filmmaking isn’t just a thing which can only be done by wealthy corporations who function thereby as the cultural gatekeepers deciding which stories will get told. Anyone who is willing to put in the work can make a film, and put it before a worldwide audience. Mind you, machinima emerged in a time before the iPhone, before YouTube and Twitch, before TikTok. Or virtual worlds like Second Life. There is now a whole universe of rapid ways to make a film, even a really good film. Many of them, admittedly, much easier than machinima, and without machinima’s legal ambiguities. (Who owns Obit?)

And then there are the emerging platforms which leverage the advantages of real-time animation, unencumbered by the intellectual property issues tarpit which machinima lives within... Unreal Engine, Unity 3D, and so on. So, many of the things which made machinima wholly unique in its infancy are no longer its exclusive purview. So it’s no wonder that activities like “photo mode” have such a draw – ease is always a big draw. Ease can mean efficiency. Ease can allow for spontaneity and experimentation. I don’t think machinima’s potential as an art form will ever be fulfilled, as long as engaging video games are being created. There is always the possibility that a future Paul Thomas Anderson will stumble upon machinima, and innovate tomorrow in ways we haven’t even thought of today.

Luca Miranda: The story that you tell with Obit is inspired by events that took place in your own life. Why did you choose Red Dead Redemption 2 to recreate this specific episode, rather than The Sims or Grand Theft Auto? Is there something inherent to the Wild West that you found particularly appealing?

Phil Rice: The decision to tell this story in movie-form at all was relatively sudden. I keep a file of story ideas and review it regularly... some ideas don’t survive the test of time and get eliminated, others (hopefully the best of the bunch) live on. I’ve been doing this distillation process for years, recognizing that I only have so much time on this earth, only so many stories I can possibly tell given that time. So what I do spend time on, it had better be worthwhile.

But this story, while based on an experience that happened to me decades ago, had never found its way into that idea file. If I’m remembering the dates correctly, the decision to tell this story, and the entire production of it, all occurred within the calendar year of 2021. It hit me out of nowhere.

RDR2 has a remarkably diverse and beautiful setting, combined with highly expressive animated characters. It’s the first time a game convinced me I could tell a compelling, meaningful story with very sparse dialogue, leaning heavily on non-verbal communication. A silent protagonist only works if he/she can communicate without speaking. It was an exciting challenge to undertake.

It wasn’t necessarily important for this story to be a Western... but the story just seemed to “click” well with that setting.

Luca Miranda: Among other things, Obit is a story about grief, loss but above all, meaning (or the lack of thereof). It is about coming to terms with a painful, if not traumatic, experience and to chastise a patronizing voice. I feel that the challenges that you encountered in the production were not only technical, but also (especially?) emotional. Did you find the process - that is, creating a narrative through a video game that incorporates a specific cinematic understanding of the Wild West, with all its tropes and conventions - cathartic? Was this experience ultimately helpful, on an affective level? Did you find some kind of closure afterwards?

Phil Rice: Oh, very much so, yes, a catharsis. Storytelling, for me, is many times a form of therapy. The Wild West setting let me tell this story in a stripped-down manner, in a simpler time when everything moved a bit slower. This was the second-most emotionally challenging real story I’ve endeavored to tell using machinima (the first being Nine Inch Nails: Only from 2007). There are bits of me sprinkled throughout all my work, a breadcrumb trail of catharsis, but Obit is certainly one of the most direct and deeply personal works I’ve attempted. For me, the challenge isn’t the fact that I’m emotionally affected by the story or content – I mean, that’s the motivator to do this. To face a fear, to confront a ghost, to process a feeling that won’t let go. The challenge is trying to find a way to tell that story which will emotionally affect those who watch it.

Luca Miranda: The main character — the cowboy on horseback at the beginning of the film — is basically silent for the entire duration of the story - save for a nervous cough that barely hides’ his anger - setting a meditative, somber mood interrupted by an emotional explosion. All the pent up rage is suddenly released and an intense beating ensues. Was this climax based on your personal experience as well, or is this outcome something that you really wanted back then but did not act upon it? is Obit a manifestation of l’esprit d’escalier as a machinima? I understand that this may be a sensitive question and I apologize in advance if it sounds inappropriate.

Phil Rice: No, that’s such a great question. My personal experience did not involve a physical, or even verbal, confrontation. Over the years, I’ve alternated back in forth in my interpretation of that fact – was it cowardice, or wise restraint? I still don’t know. I cannot say I’ve spent a lot of time fantasizing about a physical response I could have undertaken. I suppose I buy into the saying that he who takes a verbal argument to physical territory has declared himself the intellectual inferior. Or maybe that’s just a coward’s excuse. That conflicted sense of what I “should have” or “could have” done is, I think, the primary reason this story, and the memory that fuels it, still persist to this day. I mentioned “confronting a ghost” earlier – that is how I tend to think of these formative experiences that hang on so tenaciously. They are ghosts that will continue to haunt until exorcised.

So I suppose telling this story in this way is an attempt at that exorcism. It’s worth noting (SPOILER ALERT) that the intense beating in the film, well let’s just say, it isn’t what it first appears to be. In fact, it could be said to be the main character’s own l’esprit d’escalier. (And so, in a sense, mine.) The original cut of the film did not include the shots which reveal the existence of a “fantasy sequence.” That wasn’t part of the original plan. I actually went back and reshot those scenes to give that effect because the film wasn’t “saying” what I wanted to say when the beatdown was real.

Luca Miranda: Splendid vistas and sublime spaces are contrasted to the appalling lack of tact and arrogance of the Preacher. Meteorological changes reflect the character’s mood and state of mind. The beauty of (simulated) nature is juxtaposed to the sheer mediocrity of Man. The lonely cowboy immediately leaves town after the confrontation with the Preacher. It's clear that he prefers the company of his own horse and the wilderness to the meaningless chatter of the civilized world. Is misanthropy the only legitimate choice in a social context where superstition is used as an instrument of power and control?

Phil Rice: It certainly feels that way sometimes, but no, withdrawal cannot be the only choice or we are doomed. At some point, superstition must be faced down, warred against, and killed. But there’s no way to do this without hurting people, emotionally or otherwise. And most people don’t want to hurt other people, or be hurt themselves. And the people who are benefiting from those systems of power and control don’t want to let go. So it’s complicated.

Perhaps in the time in which this film was set, the cowboy could get away with fleeing. He would just be postponing the inevitable, but the world was small enough, I suppose, to let it slide. In our modern world, there are fewer and fewer places where one can go to get away from civilization. Ultimately, civilization needs to be worked on. It needs to cope with its inherent “ills” – and that’s going take more people being engaged in that task, not fewer.

Luca Miranda: The score is almost like a character in Obit. Can you describe your collaboration with Marco Simone, who composed the soundtrack of your machinima? At which point of the production did you have a score? Before or after writing a script?

Phil Rice: The script came first, and the general idea for the score came during production. I had found some music by an experimental guitar artist named Tashi Dorji on the Free Music Archive. I desperately wanted to use his music, and actually composed an early edit of the film with Tashi’s music as the score. Tashi’s music on FMA was licensed Creative Commons with No Derivatives, meaning I needed to get his permission to use it for my score. I formally requested his permission through every contact method I could dig up, but after waiting in vain for two months for a reply, I was left wondering what in the world I was going to do.

I then hired Italian artist Marco Simone from Fiverr.com’s gig network, and I was up front with him about the situation. Marco’s demo really impressed me, and he seemed to understand what I was looking for. I even shared with him the Tashi Dorji edit, but told him not to try to imitate Tashi but do his own thing in keeping with the timing of the edit.

Marco was incredible. Most of what you hear in the film are his first takes, done over a period of just a few days. I only had to make miniscule adjustments to the video edit. When I later learned that I was actually the first person to hire Marco on Fiverr, I could hardly believe it. Such a talent.

When I heard Marco’s score, I got inspired to add some dayereh drum myself. A dayereh is a hand made drum, of Persian origin I believe, played by hand. It’s like this big, beautiful tambourine with a really distinct sound and has a wonderful dynamic and tonal range. I received a dayereh as a gift several years ago and had been looking for an excuse to use it in a score.

I could not be happier with how it all turned out. Marco was very happy with the film as well, and I’m glad, because his contribution really elevated the film.

Luca Miranda: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

PHIL RICE: I’m so grateful to have my work be part of MMF. I’ve been following the festival since its inception, and am always excited to view your selections each year, inevitably discovering something new and exciting going on in machinima. Thank you very much.

Luca Miranda: Thank you so much for your time and consideration.

INTERVISTA

Luca Miranda: Hai iniziato a sperimentare con il machinima nel 1998, quando il termine “machinima” non era ancora stato coniato. Hai visto questo mezzo/formato/genere evolversi e cambiare nel corso degli anni. Cos’è il machinima per te, oggi? Ritieni che il potenziale del machinima, come forma d’arte, sia stato pienamente raggiunto? In caso contrario, secondo te cosa manca? Come spieghi l’estrema popolarità dei photo mode (modalità fotografiche) nei videogiochi alla luce della relativa scarsità di editor video/machinima nelle recenti produzioni tripla A?

Phil Rice: Santo cielo, che domanda! (ridendo)

Non possiamo parlare di machinima senza riconoscerlo come fenomeno culturale. Il machinima è emerso dapprima nel contesto di una comunità di artisti, scrittori, hacker/modder e programmatori che si dedicavano a un certo tipo di videogiochi, e hanno colto il potenziale espressivo e/o di commento sociale usando come materiale proprio quei videogiochi. Questo aspetto costituisce tuttora il fulcro del machinima, per la maggior parte dei casi. Certo, il fatto che molti titoli al giorno d’oggi includano strumenti di ripresa incorporati ha contribuito ad abbassare la soglia d’ingresso per chi vuole cimentarsi con questa pratica, ma le migliori opere machinima sono ancora basate su un soggetto che altera il videogioco, per fargli fare qualcosa che non è stato progettato per fare.

Per me, la fascinazione è sempre stata una cosa pragmatica. La grande attrattiva del machinima, dal punto di vista della produzione, è sempre stata la velocità... o, meglio, la facilità. Il machinima permette, in generale, di fare di più — e più velocemente — rispetto al cinema convenzionale e certamente delle tecniche convenzionali di animazione 3D, con meno personale e con meno costi. In ogni caso, ciò non significa che non sia difficile. Ma, relativamente parlando, è sicuramente più veloce. Grazie alla natura in tempo reale del rendering dell’animazione, a causa della capacità di sfruttare il lavoro (contenuto del gioco) di grafici professionisti, character designer e world builder.

Perché la facilità è un’aspetto importante? Beh, per prima cosa, il nostro tempo in quanto esseri umani è limittao. Meno tempo ci vuole per produrre qualcosa, più possiamo fare con quella cosa. Lo stesso vale per tutti gli aspetti economici... i nostri budget sono limitati. Tutto ad un tratto, il cinema non è una cosa che può essere fatta solo da grandi studio che agiscono come veri e propri guardiani culturali, in grado di decidere quali storie che verranno raccontate. Chiunque abbia voglia di sporcarsi le mani con il digitale, può realizzare un film e proporlo a un pubblico mondiale.

Intendiamoci, il machinima è emerso in un’era precedente all’iPhone, prima di YouTube e Twitch, prima di TikTok. E prima dei mondi virtuali come Second Life. Oggi c’è un intero universo di modi rapidi per fare un film, anche un film di qualità. Molti, è vero, sono molto più comodi del machinima e senza le ambiguità legali che lo contraddistinguono. (Per esempio, chi possiede Obit?)

E poi ci sono le piattaforme emergenti che sfruttano i vantaggi dell’animazione in tempo reale, svincolate dai problemi di proprietà intellettuale in cui vive il machinima... Unreal Engine, Unity 3D, e così via.

Così, molte delle cose che hanno reso il machinima del tutto unico nella sua infanzia non sono più di sua esclusiva competenza. Quindi non c’è da meravigliarsi che attività come il photo mode oggi esercitino una tale attrazione — la facilità è sempre una grande attrazione. La facilità può significare efficienza. La facilità può permettere la spontaneità e la sperimentazione.

Non credo che il potenziale del machinima come forma d’arte verra mai pienamente realizzato, finché verranno creati videogiochi coinvolgenti. C’è sempre la possibilità che un futuro Paul Thomas Anderson si imbatta nel machinima e innovi il domani in modi a cui oggi non abbiamo ancora immaginato.

Luca Miranda: La storia che racconti con Obit è ispirata a eventi realmente accaduti nel corso della tua vita. Perché hai scelto Red Dead Redemption 2 per ricreare questo episodio specifico, piuttosto che The Sims o Grand Theft Auto? C’è qualcosa inerente al selvaggio West che hai trovato particolarmente attraente?

Phil Rice: La decisione di raccontare questa storia in forma di film è stata relativamente improvvisa. Mantengo un archivio di idee di storie e lo riesamino regolarmente... alcune idee non sopravvivono alla prova del tempo e vengono eliminate, altre (le migliori del gruppo, almeno si spera) continuano a vivere. Ho proseguito con questo processo di distillazione per anni, riconoscendo che il mio tempo su questa terra è limitato, come dicevo prima, pertanto c’è un tot numero di storie che posso raccontare nel lasso di tempo che mi è concesso. Quindi, è per me importante didicarmi appieno solo ai progetti a cui credo davvero.

Ma questa storia, pur essendo basata su un’esperienza che mi è accaduta decenni fa, non aveva mai trovato la sua strada in quel file di idee. Se ricordo bene le date, la decisione di raccontare questa storia, e l'intera produzione, è avvenuta nell'anno solare 2021: è stata come un’epifania. All’improvviso, ho deciso che era arrivato il momento giusto per realizzarla.

RDR2 ha un’ambientazione straordinariamente varia e bella, con l’aggiunta di personaggi animati molto espressivi. È la prima volta che un videogioco mi ha convinto cxhe fosse possibile raccontare una storia avvincente e significativa con un dialogo molto scarno, sfruttando la comunicazione non verbale. Un protagonista silenzioso funziona solo se può comunicare senza parlare. È stata una sfida eccitante da intraprendere.

Non era necessariamente importante che questa storia fosse un western... ma la storia sembrava “combaciare” bene con quell’ambientazione.

Luca Miranda: Tra le altre cose, Obit è una storia sul dolore, sulla perdita ma soprattutto sul significato (o la sua mancanza). Si tratta di fare i conti con un’esperienza dolorosa, se non traumatica, e di castigare una voce paternalista. Percepisco che le sfide che hai incontrato nella produzione non sono state solo tecniche, ma anche (soprattutto?) emotive. Hai trovato questo processo — ovvero creare una narrazione attraverso un videogioco che incorpora una specifica concezione cinematografica del selvaggio West, con tutti i suoi tropi e convenzioni — catartico? Questa esperienza è stata alla fine utile, a livello affettivo? Hai raggiunto una specie di conclusione, di chiusura, al termine del lavoro?

Phil Rice: Oh, molto, sì, una catarsi. Per me, lo storytelling è spesso una forma di terapia. L’ambientazione del selvaggio West mi ha permesso di raccontare questa storia in modo essenziale, senza fronzoli, in un’era più semplice in cui la vita scorreva un po’ più lentamente.

Questa è stata la seconda storia reale emotivamente più impegnativa che ho cercato di raccontare usando il machinima. La prima è stata Nine Inch Nails: Only del 2007. Ci sono frammenti della mia identità sparsi in tutto nelle mie opere, una scia di briciole di catarsi, ma Obit è certamente uno dei lavori più diretti e profondamente personali tra tutti quelli in cui mi sono cimentato.

Per me, la sfida non è il fatto di essere emotivamente colpito dalla storia o dal contenuto — intendo dire, questo è il motivo per cui lo faccio. Affrontare una paura, confrontarsi con un fantasma, elaborare un sentimento che non vuole lasciarsi andare. La sfida è cercare di trovare un modo per raccontare quella storia che colpisca emotivamente chi la guarda.

Luca Miranda: Il personaggio principale — il cowboy a cavallo all’inizio del film — mantiene un austero silenzio per tutta la durata della storia — salvo un colpo di tosse nervoso che nasconde a malapena la sua rabbia — creando così un’atmosfera meditativa e cupa, interrotta da un’inattesa esplosione emotiva. Tutta la rabbia repressa viene improvvisamente liberata. Ne coinsegue un violento pestaggio. Anche questo climax era basato sulla tua esperienza personale, oppure è un qualcosa che desideravi all’epoca ma che non hai messo in atto? In altre parole, Obit è una manifestazione dell’esprit d’escalier sotto forma di machinima? Capisco che questa possa essere una domanda delicata e mi scuso in anticipo se è inappropriata.

Phil Rice: No, questa è un’ottima domanda. La mia esperienza personale non ha culminato né in uno scontro fisico né in uno verbale. Nel corso degli anni, ho alternato più volte la mia interpretazione di questo fatto – è stata codardia oppure saggia moderazione? Ancora non lo so. Non posso dire di aver passato molto tempo a fantasticare su una risposta fisica che avrei potuto intraprendere. Suppongo di aver seguito il detto che colui che porta una discussione verbale in territorio fisico si dichiara l’intellettualmente inferiore. O forse è solo la scusa di un codardo.

Questo senso conflittuale di ciò che “avrei dovuto” o “potuto” fare è, credo, la ragione principale per cui questa storia, e il ricordo che la alimenta, persistono ancora oggi. Prima ho parlato di “affrontare un fantasma” — è così che tendo a pensare a queste esperienze formative che restano aggrappate così tenacemente. Sono fantasmi che continueranno a perseguitare finché non saranno esorcizzati. Quindi suppongo che raccontare questa storia, in questo modo, rappresenti un tentativo di esorcismo.

Vale la pena notare che il furioso pestaggio nel film, beh, diciamo solo che non è quello che sembra a prima vista. In effetti, si potrebbe dire che è l'esprit d'escalier del protagonista (e quindi, in un certo senso, il mio). Il montaggio originale del film non includeva le inquadrature che rivelano l’esistenza di una “sequenza di fantasia”. Non faceva parte del piano originale. In realtà sono tornato indietro e ho rigirato quelle scene per conferire quell’effetto, perché il film non “diceva” quello che volevo esprimere nel momento in cui il pestaggio era reale.

Luca Miranda: Splendidi panorami e spazi sublimi si contrappongono alla spaventosa insensibilità e arroganza del Predicatore. I cambiamenti meteorologici riflettono l’umore e lo stato d'animo del personaggio. La bellezza della natura (simulata) è giustapposta alla pura mediocrità dell’uomo. Il cowboy solitario lascia immediatamente la città dopo il confronto con il Predicatore. È chiaro che preferisce la compagnia del suo cavallo e la natura selvaggia alle chiacchiere senza senso del mondo civilizzato. La misantropia è l’unica scelta legittima in un contesto sociale dove la superstizione è usata come strumento di potere e controllo?

Phil Rice: Certamente ci si sente così a volte, ma no, il ritiro non può essere l’unica scelta, o siamo condannati. Ad un certo punto, la superstizione deve essere affrontata, combattuta e uccisa. Ma non c’è modo di farlo senza ferire le persone, emotivamente o in altro modo. E la maggior parte delle persone non vuole ferire altre persone, o essere ferita a sua volta. E le persone che stanno beneficiando di quei sistemi di potere e controllo non vogliono lasciarli andare. È complicato.

Forse, nell’epoca in cui questo film è ambientato, il cowboy potrebbe cavarsela fuggendo. Avrebbe solo rimandato l’inevitabile, ma il mondo era abbastanza piccolo, suppongo, da poter lasciar correre. Nel nostro mondo moderno, ci sono sempre meno posti dove si può andare per fuggire dalla civiltà. In definitiva, la civiltà ha bisogno di essere rifinita. Ha bisogno di far fronte ai suoi “mali” intrinseci — e questo richiederà più persone impegnate in questo compito, non meno.

Luca Miranda: La colonna sonora risulta quasi come un personaggio in Obit. Puoi descrivere la tua collaborazione con Marco Simone, che ha composto la colonna sonora del tuo machinima? A che punto della produzione avevate elaborato una partitura? Prima o dopo aver scritto la sceneggiatura?

Phil Rice: La sceneggiatura è venuta prima e l’idea generale per la colonna sonora è soggiunta in fase di produzione. Avevo trovato della musica di un chitarrista sperimentale di nome Tashi Dorji su Free Music Archive. Volevo disperatamente usare la sua musica e, in effetti, ho elaborato un primo montaggio del film con la musica di Tashi come colonna sonora. La musica di Tashi su FMA aveva una licenza Creative Commons No Derivatives, il che significa che dovevo ottenere il suo permesso per usarla nella mia colonna sonora. Ho richiesto formalmente il suo permesso attraverso ogni metodo di contatto che sono riuscito a trovare, ma dopo aver aspettato invano una risposta per due mesi, sono rimasto a chiedermi cosa avrei potuto fare.

Ho quindi assunto l’artista italiano Marco Simone attraverso Fiverr.com, e sono stato sincero con lui sulla situazione. La demo di Marco mi ha davvero impressionato, e sembrava comprendere quello che stavo cercando. Ho anche condiviso con lui il montaggio di Tashi Dorji, ma gli ho detto di non cercare di imitare Tashi bensì di fare le sue cose in linea con il tempo del montaggio.

Marco è stato incredibile. La maggior parte di ciò che si sente nel film sono le sue prime riprese, fatte nell’arco di pochi giorni. Ho dovuto fare solo minuscoli aggiustamenti al montaggio video. Quando più tardi ho saputo che ero stata la prima persona ad assumere Marco su Fiverr, non riuscivo a crederci. Un tale talento.

Quando ho sentito la colonna sonora di Marco, ho avuto l’ispirazione di aggiungere io stesso qualche tamburo dayereh. Un dayereh è un tamburo fatto a mano, di origine persiana credo, suonato a mano. È come un grande e bellissimo tamburello con un suono davvero distinto e ha una meravigliosa gamma dinamica e tonale. Ho ricevuto un dayereh come regalo diversi anni fa e stavo cercando una scusa per usarlo in una partitura.

Non potrei essere più soddisfatto per come è andata a finire. Anche Marco era molto contento, e ne sono felice, perché il suo contributo ha davvero contribuito a impreziosire il film.

Luca Miranda: Vorresti aggiungere qualcos’altro?

Phil Rice: Sono grato che il mio lavoro faccia parte del Milan Machinima Festival. Ho seguito il festival fin dall’inizio e sono sempre entusiasta di vedere le vostre selezioni ogni anno, scoprendo inevitabilmente qualcosa di nuovo ed eccitante nel contesto del machinima. Apprezzo molto la vostra dedizione.

Luca Miranda: Grazie a te per il tuo tempo e la tua considerazione.

OBIT

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 13’ 41”, 2021, United States

Director, Writer, Producer: Phil Rice

Cast: Phil Rice as “Preacher”

Music composer: Marco Simone

Editor: Evan Ryan

Made with Red Dead Redemption 2 (Rockstar Games) and several mods including Map Editor 0.6.1 by Lambdarevolution

See movie credits for full list of mods