KELLY RABBACHIN

BAD TALES

MARCH 21-27 2022/21-27 MARZO 2022 (ONLINE)

Introduced by/Introdotto da Matteo Bittanti

THE RABBIT HOLE

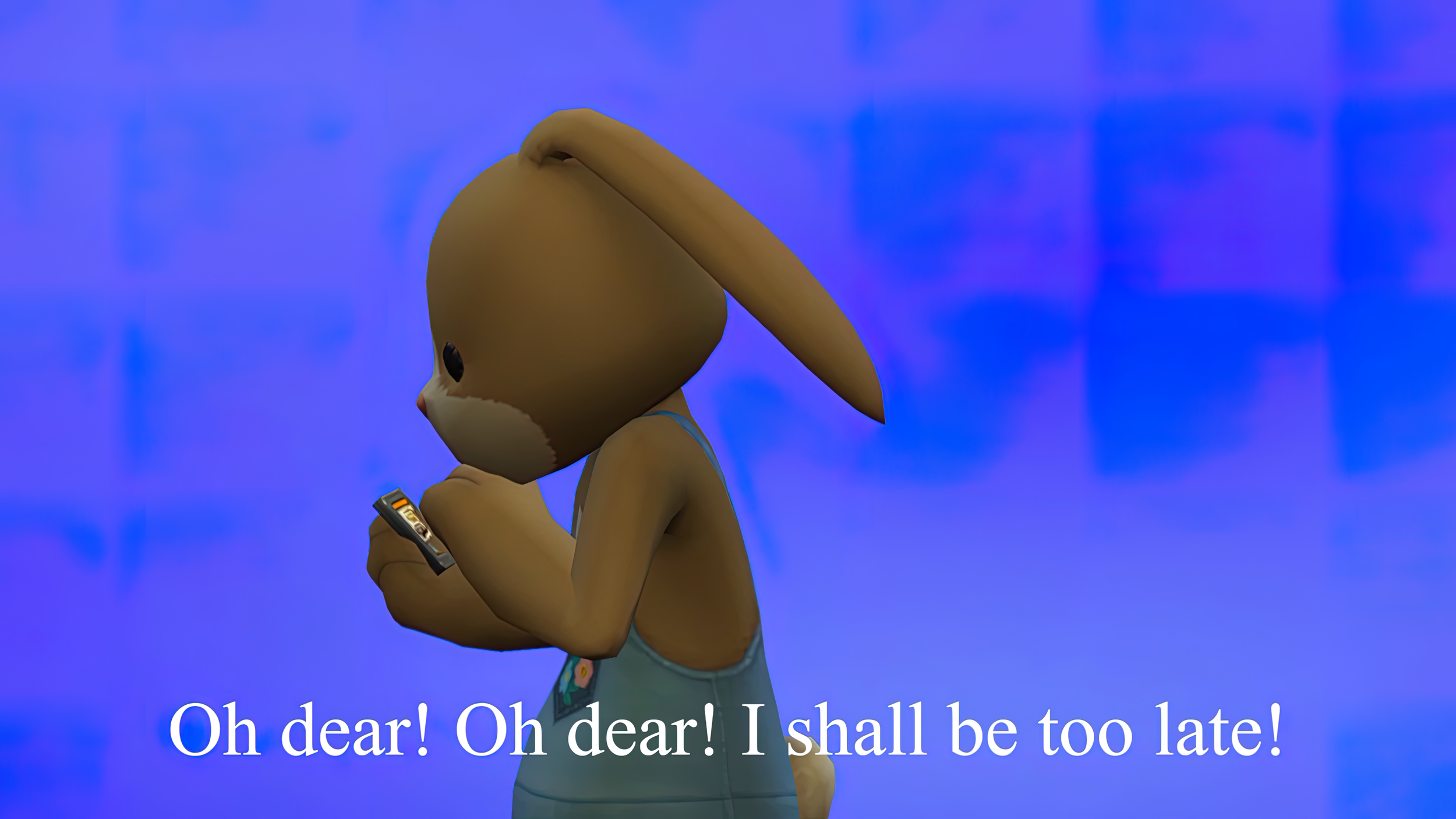

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 9’ 50”, 2021, Italy

For an optimal experience, we strongly recommend a desktop browser and fullscreen mode on.

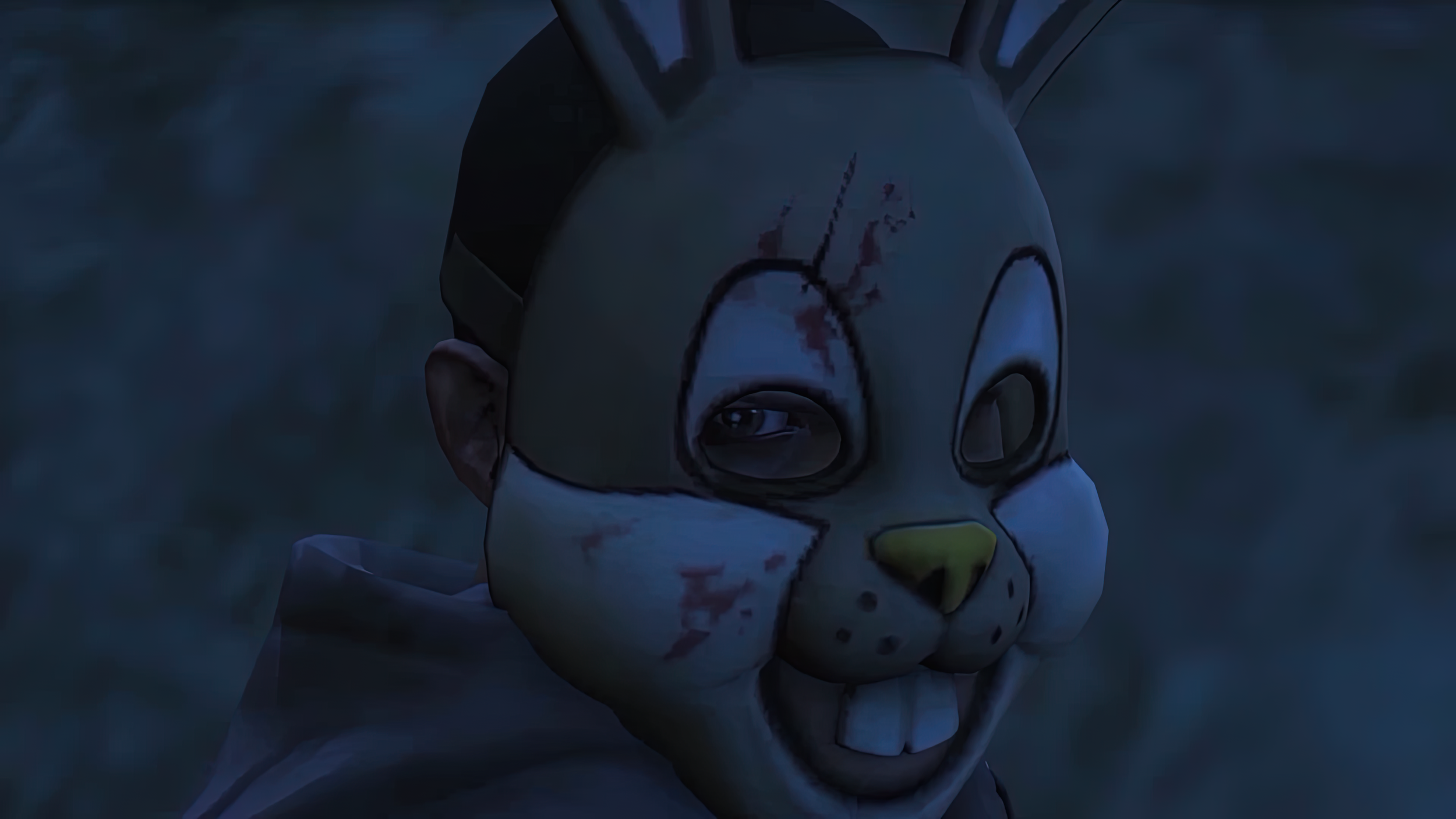

Un bambino solitario in cerca di avventure scorge un coniglio gigante. Inseguendo il misterioso roditore nella sua tana, si ritrova intrappolato in un mondo desolato e minaccioso. Dopo una serie di incontri inquietanti, si rende conto di aver lasciato il paese delle meraviglie per sempre. Questo remake sui generis del racconto di Lewis Carroll è stato creato con/in Grand Theft Auto V e The Sims 4.

A lonely child looking for adventure sees a giant rabbit. Chasing the mysterious rodent down the rabbit hole, he finds himself trapped in an desolate, sinister world. After a series of increasingly unsettling encounters, he realizes that he left Wonderland for good. This remake sui generis of Lewis Carroll’s story was created with/in Grand Theft Auto V and The Sims 4.

L’ARTISTA

THE ARTIST

Kelly Rabbachin è una giovane creativa la cui pratica include media come la fotografia, il video, il design grafico e l’illustrazione. Esplora le convenzioni specifiche e l’estetica di ogni medium per capire come rappresenta — spesso reinventa — la realtà come la conosciamo. Rabbachin si è laureata con lode in Nuove Tecnologie dell’Arte presso l’Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, Milano.

Kelly Rabbachin is a young creative whose practice spans different media including photography, video, graphic design, and illustration. She is interested in exploring the specific conventions and aesthetics of each medium to see how they represent — often reinvent — reality as we know it. Rabbachin received a B.A. cum laude in New Technologies of Art from the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera, Milan.

INTERVIEW

Matteo Bittanti: The Rabbit Hole was originally developed as part of your thesis project at the Academy of Fine Arts of Brera. In other words, you learned about machinima by making machinima, which is perhaps the most effective approach. Can you describe your process?

Kelly Rabbachin: I “discovered” machinima as a new expressive and creative tool in a rather ironic way: during the first wave of Covid-19 and the following months under lock down, I began to pay attention to Twitch.tv, and its plethora of live-streaming channels hosted by amateurs, where in most cases, video game performances are presented in real time. As I was exploring this new territory — new to me, at least — I came across a quite peculiar live-streaming of Grand Theft Auto V: the streamer, who was off screen — which is quite rare within this platform — was playing a role, as if he were an actor, together with other players who were doing exactly the same. Such manner of playing struck me as peculiar: users had agreed to play as actors in a movie or a play, disregarding the intended narrative: in short, they had turned their avatars into performers and the game world into a stage.

I remember watching the broadcast for a few hours, completely enthralled and yet without understanding if what I was witnessing was a scripted performance or the result of skilled improvisation. What I did not know back then is that this style of playing is part of the mod GTA RP, or a modified version of GTA Online where users perform through role play, that is, they adhere to a clearly defined role in specific dedicated servers, and follow strict rules shared by all players, under penalty of a perma-ban if they violate such agreement.

I was fascinated by the idea of giving an avatar a persistent — and yet completely made up — role as if their identity was fixed. I was interested in the emergent gameplay generated by such a decision. Suddenly, a light bulb went on in my head. All I wanted to do was to make a movie within a video game, where the avatar would be my leading actor. I would be calling the shots, like a fully fledged director. Imagine that! A groundbreaking project! [laughs] I genuinely believed that no one had ever done such a thing. All it took was a quick Google search to realize that my “original” project had a long history. This format had already been experimented by several experienced gamers and artists working in the field of experimental cinema and video art. It even had a name: ma-chi-ni-ma. I was floored.

Around the same time, I began researching for my thesis in the program of New Technologies of Art at the Academy of Art in Brera, Milan. Clearly, I wanted to investigate the practice of machinima. In my thesis, I discuss its origins and development, examining both the amateur practice within the culture of modding, that is, the first narrative machinima created by appropriating popular first-person shooters such as Quake, but I also discuss the more explicitly artistic practice within the field of machinima. I talk about artists that used this emerging medium to investigate the relationship between the real world and simulated reality. In order to situate machinima within the current media landscape, I examine the process behind the creation of machinima, a mix of remediation — in Bolter and Grusin’s sense — and appropriation. I write how, within the hypermediated environment of Web 2.0, users create new content by picking and choosing assets from an ever expanding online digital archive. With the advent of YouTube and Twitch.tv, social media, and blogging, the idea of passively consuming media content became obsolete. Users became co-producers of the same products they once consumed passively. In doing so, they became active forces within the web. Machinima has been examined as a paradigmatic example of user generated content, in line with the technological evolution of the digital media landscape: the video game is no longer simply a product of the entertainment industry, but has become a creative tool in the hands of skilled filmmakers. My take is that it is currently difficult to imagine a future in which machinima will achieve the same kind of cultural legitimacy as previous media such as cinema and digital animation. After all, it is still “an emerging medium”. However, I believe that the technological progress made by video games and the evolution of the concept of simulated reality in general will provide new insights into machinima, and will allow for the development of new artistic forms within a Web 2.0 — and beyond — context: I predict that digital places and simulated worlds will become more and more popular, highlighting the fact that the boundaries between real and virtual have never been more porous. Artists will find fertile ground to experiment within these new spaces. They will investigate the relationship between real and simulation through novel creative processes; only then, perhaps, machinima will be finally recognized as an autonomous medium.

Matteo Bittanti: I feel like we’re living in the early Zeroes again: I’m having a deja vu. The recent brouhaha about the metaverse brought back themes that many thought anachronistic. Never underestimate the Zuck’s hype machine, I guess. Having clarified your role as a new practitioner of machinima, can you discuss your relationship with the video game medium?

Kelly Rabbachin: I’ve been playing video games pretty much forever. Over the years, I’ve tried most, if not all, the genres: from triple A titles to indie games and art games. I spent an inordinate amount of time with retro gaming. I play for fun, but also to test my abilities: video games require very specific skills such as concentration, patience, problem solving, memory, perseverance, ingenuity, and hand-eye coordination. I believe that the skills that I develop by playing video games can also be useful in real life. Video games that emphasize exploration over destruction, such as the Grand Theft Auto series, are my favorites: in addition to having to complete a series of missions, goals and side quests scattered around the game map, I like to wander around and take photographs, discovering hidden areas, Easter eggs, bugs and so on. I find it relaxing to drive across San Andreas, without feeling that I must complete a mission. I just drive around aimlessly hoping to run into some place that I have not yet seen. To me it’s like traveling to another world, with the advantage of having more resources. I do not deny that at times I used video games as an escape from reality. They are a safe place to me, a place where the problems of everyday life can be momentarily suspended. But even in these situations, I am aware that game worlds are — in fact — places that fully exist, they are real and not just a mere background for the actions of the avatar: the player really does enter into a fully functional world and does become, in most cases, its semi-god. The time and dedication that we put into playing video games makes us gradually more capable and skilled, more aware of the rules and limits of the virtual dimension; similarly, we face the same learning curve in the so-called real life: we face challenges and we must choose our paths. You win some, you lose some. I am fascinated by the relationship between the real world and simulated reality, between the player and the avatar. In some ways, it might seem like a dangerous relationship, but I believe that finding a balance between these two dimensions is essential to grow and evolve, to better understand the world we live in today.

Matteo Bittanti: In this work of appropriation and reinterpretation, you chose a fairy tale to hybridize different narratives. Why this format?

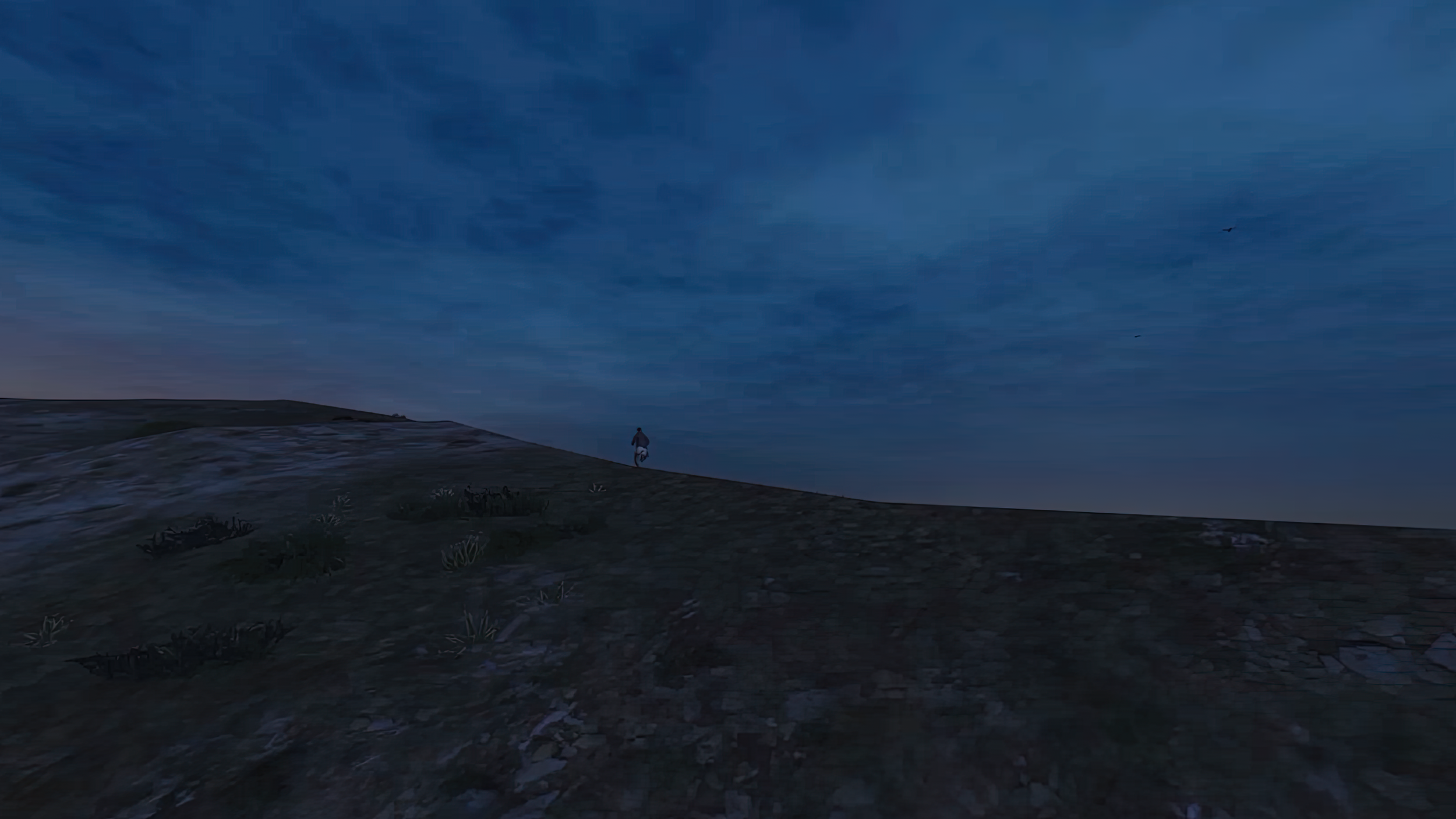

Kelly Rabbachin: I could list several reasons why I remediated Alice in Wonderland for my machinima. First and foremost, Lewis Carroll’s literary work is extremely popular: almost everyone knows the original, or at least a version of it. By repurposing this tale, I could therefore assume an audience already familiar with the tropes and characters. Recontextualizing Carroll in video game form saves me a lot of work when it comes to characterization and storytelling. Secondly, a machinima based on Alice in Wonderland felt like the perfect story for the video games that I appropriated, The Sims 4 and Grand Theft Auto V: in the original Alice goes down the rabbit hole and ends up in Wonderland. Meanwhile, the protagonist ofThe Rabbit Hole finds himself in a new world, literally, a new game world, which I hoped would create a sense of cognitive dissonance in the viewer. Since this was my first attempt at machinima and having to present it as the final project of my thesis, The Rabbit Hole had to clearly communicate all the key features of the medium: in addition to 3D environments generated by game engine, I had to make sure that the committee would understand how machinima strongly relies on the practice of appropriation and remediation both technically and narratively. In order to stress the notion of remediation, instead of creating a story from scratch, I recycled and updated an existing script, taking only the elements that were useful for my narrative goals, and then I deliberately manipulated them to create something else. In fact, the original narrative is disrupted when my character is catapulted into the world of Grand Theft Auto. A fantastic adventure in Wonderland suddenly turns into a nightmare. I created such contrast to build a tense, unnerving atmosphere, and in a way, to evoke a specific kind of mood in the viewer. To create The Rabbit Hole, I diverged from the original story as much as from the video game text itself, removing the intense action and steady pace from the latter, shooting empty, desolate environments, relying on long, fixed camera shots. I was inspired by Phil Solomon’s poetic machinima, by Ruben Ostlund’s cinematic style and by Gus Van Sant’s laconic films, especially Last Days, which I openly quoted in the opening shot of my machinima. In short, I wanted to create a story with feelings rather than plot twists. I was not interested in a multi-layered narrative. All I wanted to do was to visualize a sense of disappointment, alienation, escapism, friendship, loneliness and violence just by relying on editing.

Matteo Bittanti: The Rabbit Hole combines two different machinima: The Sims and Grand Theft Auto, probably the most used videogames to create non-interactive audiovisual narratives. In both cases, the respective developers have encouraged the creation of machinima by inserting tools and editors directly into the video games. However, this facilitation represents the exception to the norm. Today, in fact, developers seem to have favored the logic of the photo mode and therefore of the recreational photo over that of the movie editor in the most recent video games. and therefore of the machinima How do you explain this paradigm shift? Why the emphasis on still images instead of moving images?

Kelly Rabbachin: In my opinion, nowadays developers prefer not to include video recording tools because they are aware that widely available, dedicated programs are considerably more powerful: if we take as an example the video recording tool integrated in The Sims 4, it’s obvious even for a neophyte that the resulting video does not have the same image quality of the actual gameplay. It is therefore more efficient to use external tools to record game sessions, such as OBS Studio or the Xbox Game Bar in Windows; this is especially true for users who mostly play video games on PC, a segment of the market that has been steadily growing in the past few years. Compared to the editors embedded within specific games or platforms, these dedicated tools allow the player to record long sessions without compromising the quality of the outcome. Besides, most of the users who play video games are not that interested in recording their game sessions, thus these tools are useful only for a limited numbers of power users; an exception is the replay recording tool and the” share button”, which are used by gamers to store particularly striking events on their hard drive or in the cloud and then circulate them on social media. In short, I believe that developers — who are generally very attentive to the demands of the fanbase — are aware that external recording tools are more flexible and powerful than those embedded within video games or consoles. They are well aware that dedicated tools are easily accessible to skilled users who want to create gaming related content, so developing them from scratch makes little economic sense. The Rockstar Editor embedded in Grand Theft Auto V is the proverbial exception to the rule: this tool is incredibly advanced. Players can apply a variety of special effects to their recorded sessions, change their shots, edit various sequences. This tool uses the same format and functions of a standard video editor and the learning curve is relatively low. In addition, Rockstar Games provides an ad hoc space for hosting and sharing videos created with its Editor, thus encouraging the creation of this kind of content. An immense game map, a plethora of environments, the impressive diversity of venues, the open world nature of the game, are all factors that make Grand Theft Auto V the ideal game to make machinima and Rockstar Games is well aware of it. I mean, this game is still selling like hotcakes almost a decade after its introduction. I don’t see why developers would want to discourage video recording in favor of a mere photographic tool. At any rate, inserting a tool that allows players to take a screenshot is much easier and cheaper than providing a useful app for video recording, which probably explains why photo modes are proliferating.

Matteo Bittanti: What is the perception of machinima at the Academy of Fine Arts in Milan? Do you think there is an avant-garde machinima community in Italy?

Kelly Rabbachin: Funny you ask. When I first mentioned machinima as a topic for my thesis to potential advisers, no one actually knew what I was talking about. They repeatedly turned me down for that reason. Others openly and firmly rejected my idea, stating — without much knowledge, dare I say — that machinima lacks artistic value; “It’s stuff for nerds”, which does not bode well for an art school environment... To be honest, this kind of feedback did not surprise me, because even today video games are not valued for their artistic value, unlike previous media such as film and video art, which rely on an older and more conservatice audience. Luckily, I was able to find some professors willing to assist me in my quest to explore machinima as a new experimental medium. In my view, machinima does represent a new technological evolution within the art context. After extensive research, I learned about the work of Marco Cadioli, a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts in Brera, who has made several machinima throughout his artistic career, which centers on digital art. I came to the conclusion that even today machinima is understood and appreciated only by a niche comprising mostly artists and scholars. It lacks the aura of a medium in its own right, and it is still too often associated within the larger group of video art and net.art: for these reasons, I do not think there is today an Italian community dedicated to machinima as an artform, save rare exceptions. One can find small spaces within larger platforms or communities, which are international in nature rather than local: I’m talking, for example, about the subreddit r/Machinima, where users from all over the world upload their videos, discuss their practice, share tips and suggestions. However, it is a far cry from the now defunct Machinima.com network, which back in the day was extremely popular in the United States and played a key role in broadening the appeal of machinima within the mainstream. In my opinion, machinima today is experiencing some kind of stagnation: video sharing sites are overwhelmed with vernacular machinima which tend to be self-referential and shamelessly promotional. The audience of such content is mostly the same people who play the games. This is not a bad thing per se: after all, video games are a dominating force within popular culture and are, in many cases, more successful than cinema. However, for machinima to become a true artform, what is needed is more experimentation and creativity. Machinima must decisively go beyond gaming and cinema.

INTERVISTA

Matteo Bittanti: Come e quando hai deciso di cimentarti con il machinima? La tua opera integra e insieme espande il tuo progetto di tesi. Cosa hai appreso svolgendo la tua ricerca teorica e pratica su questa forma di video arte?

Kelly Rabbachin: La scoperta del machinima come nuovo strumento espressivo e creativo è avvenuta in modo abbastanza ironico: durante la prima ondata di Covid-19 e i conseguenti mesi di lockdown, ho iniziato ad interessarmi alla piattaforma Twitch.tv, il network digitiale che racchiude al suo interno canali in live-streaming condotti da utenti amatoriali, dove nella maggioranza dei casi, vengono riprese performance videoludiche in tempo reale. Esplorando la piattaforma mi sono imbattuta in una live-streaming di Grand Theft Auto V abbastanza particolare: lo streamer, che non appariva nella schermata della trasmissione — cosa abbastanza rara all’interno della piattaforma —, stava recitando una parte, come se fosse un attore, assieme ad altri giocatori che facevano lo stesso. Questo modo di giocare in multiplayer mi ha immediamente colpito: degli utenti si erano messi d’accordo per giocare in modo insolito, non previsto dal titolo originale: in breve, avevano trasformato i loro avatar in attori e il mondo di gioco in un teatro.

Ricordo di essere rimasta a guardare la trasmissione per qualche ora, incantata, senza capire se quello che stavo guardando fosse una performance sceneggiata oppure improvvisata. Ciò che ancora non sapevo è che questo modo di giocare faceva parte della mod GTA RP, ovvero una versione modificata di GTA Online, dove gli utenti giocano attraverso la modalità role play, ossia interpretando in tutto e per tutto un ruolo, all’interno di specifici server dedicati con regolamento ben preciso a cui attenersi, pena il ban dal server.

L’idea di guidare il proprio avatar interpretando un ruolo e l’utilizzo imprevisto del mondo di gioco mi hanno affascinato al punto da stimolare un’idea: volevo creare un filmato registrato interamente all’interno di un videogioco, dove l’avatar sarebbe stato il mio attore protagonista da dirigere a mio piacimento. Credevo genuinamente che nessuno avesse mai fatto una cosa del genere. Mi è bastata una veloce ricerca su internet per capire che ciò che volevo fare era già stato sperimentato da decenni (!) da diversi videogiocatori esperti e da artisti che operano nel mondo del cinema sperimentale e della videoarte, e che questo processo aveva persino un nome (!): machinima. Mi si è letteralmente aperto un mondo.

Nello stesso periodo iniziavo il mio percorso di ricerca e studio per la tesi di laurea in Nuove Tecnologie dell’Arte: ho capito immediatamente che il machinima sarebbe stato il tema della mia tesi che volevo e l’argomento da approfondire. Nella tesi ripercorro la storia del machinima, prendendo in esame sia la pratica amatoriale nata dal fenomeno del modding, dei primi machinima che utilizzano gli sparatutto in prima persona come base delle loro narrazioni, sia gli artisti che si sono cimentati con il machinima per indagare le relazioni tra mondo reale e realtà simulata. Per inserire il machinima nell’attuale panorama mediale, tratto i processi alla base della creazione machinima, ovvero di rimediazione e appropriazione, di come, all’interno dell’ambiente ipermediato del Web 2.0, i singoli utenti sono chiamati a realizzare contenuti disponendo di materiali provenienti dalla totalità dei medium digitalizzati. Infatti, la creazione di canali YouTube e Twitch, i social network, i blog, rendono obsoleta la concezione di una fruizione unicamente passiva dei contenuti: gli utenti sono ora i creatori degli stessi prodotti che fruiscono, partecipando attivamente e proponendo nuove forme di contenuti all’interno del web. Il machinima è un esempio paradigmatico di user generated content, perfettamente in linea con l’evoluzione tecnologica del panorama mediale attuale: il videogioco non è più unicamente un prodotto dell’industria dell’intrattenimento, ma diventa in questo caso uno strumento creativo. Trattandosi di un medium emergente, in fase di definizione, ho concluso che è difficile stabilire ora come ora un futuro dove il machinima abbia un vero e proprio posto legittimo all’interno del panorama mediale, al pari dei media del passato come il cinema e l’animazione digitale. Credo però che il progresso tecnologico dei videogiochi e l’evoluzione del concetto di realtà simulata in generale potranno offrire nuovi spunti di riflessione sul machinima, spiegare lo sviluppo di nuove forme artistiche che in futuro si svilupperanno all’interno del Web 2.0: i luoghi digitali, i mondi simulati, prenderanno sempre più spazio, assottigliando il confine tra reale e virtuale. L’arte troverà terreno fertile per sperimentare nuovi processi creativi e raccontare la relazione tra reale e simulazione; forse, solo allora, il machinima verrà riconosciuto come medium autonomo, dotato del proprio statuto.

Matteo Bittanti: Mi sembra di vivere di nuovo nei primi anni Zero: Sto avendo un deja vu. Il recente clamore sul metaverso ha riportato in auge temi che molti ritenevano anacronistici. Mai sottovalutare la macchina dell'hype di Zuck, credo. Avendo chiarito il tuo ruolo di nuovo praticante di machinima, puoi parlare del tuo rapporto con il mezzo videoludico?

Kelly Rabbachin: Gioco ai videogiochi da sempre e negli anni ho esplorato un po’ tutti i generi: dai titoli tripla A fino agli indie games e agli art games, esplorando in lungo e in largo il retrogaming. Gioco per divertirmi, ma anche per mettere alla prova le mie abilità: i videogiochi in generale richiedono capacità ben specifiche quali concentrazione, pazienza, problem solving, memoria, costanza, ingegno, coordinazione. Trovo che le abilità che sviluppo nei videogiochi possano essermi utili anche nella vita reale. I videogiochi che privilegiano un approccio esplorativo, come la saga di Grand Theft Auto, sono i miei preferiti: oltre ad avere una serie di missioni e obiettivi sparsi per la mappa di gioco, mi piace gironzolare alla scoperta di scorci da fotografare, aree nascoste, easter egg, bug, ecc. Mi rilassa ad esempio girare in macchina per la mappa di gioco di Grand Theft Auto V, senza il bisogno di affrontare missioni, semplicemente guidare senza meta sperando di imbattermi in qualche luogo che non ho ancora visto. Per me è come viaggiare in un altro mondo, con il vantaggio di avere maggiori risorse; non nego che in certi periodi abbia usato i videogiochi come fuga dalla realtà, trovando in essi un luogo sicuro dove i problemi della vita di tutti i giorni svanivano. Ma proprio in queste situazioni sono giunta alla conclusione che i mondi di gioco sono di fatto luoghi realmente esistenti, che non sono mero sfondo alle azioni dell’avatar: il videogiocatore entra realmente per il lasso di tempo della sessione di gioco a far parte di quel mondo e a diventarne, nella maggioranza dei casi, il sovrano. Il tempo e la dedizione che investiamo nel videogiocare ci rende man mano più capaci e abili, più consapevoli delle regole e dei limiti di una certa dimensione; allo stesso modo, affrontiamo la vita reale, che ci pone davanti a delle sfide e delle scelte durante la nostra crescita, imparando durante gli anni come affrontare sfide sempre più difficili. Mi affascina la relazione tra il mondo reale e la realtà simulata, tra l’uomo e l’avatar. Per certi versi potrebbe sembrare una relazione pericolosa, ma credo che trovare un equilibrio tra queste due dimensioni sia fondamentale per crescere ed evolverci, per capire meglio il mondo in cui viviamo oggi.

Matteo Bittanti: In questo lavoro di appropriazione e di reinterpretazione, ha scelto il formato della favola per ibridare differenti narrazioni. Perché la fiaba, in particolare?

Kelly Rabbachin: Ci sono diverse ragioni per cui ho utilizzato la favola di Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie per il mio machinima. Innanzitutto, l’opera letteraria di Lewis Carrol è un racconto praticamente universale, noto a tutti, o quasi. In questo modo, il machinima prende avvio da una base narrativa chiara e comprensibile alla maggior parte del pubblico e ciò crea un’aspettativa di carattere narrativo. In secondo luogo ho voluto utilizzare proprio questo racconto perchè era perfetto per mescolare i due differenti videogiochi che ho utilizzato, The Sims 4 e Grand Theft Auto V: come Alice, cadendo nel buco del Bianconiglio, è catapultata nel Paese delle Meraviglie, allo stesso modo il personaggio di The Rabbit Hole, si ritrova in un nuovo mondo, in questo caso un nuovo mondo di gioco.

Inoltre, trattan dosi del mio primo vero e proprio machinima e dovendolo presentare come progetto finale di tesi, The Rabbit Hole doveva possedere al suo interno tutte le caratteristiche essenziali di un machinima: oltre all’utilizzo di ambientazioni create dal motore grafico 3D, i concetti che dovevo mettere in evidenza erano quelli dell’appropriazione e della rimediazione di medium precedente in favore di un racconto inedito. Invece di creare un racconto del tutto nuovo, per rafforzare il concetto di rimediazione, ho voluto sfruttare un racconto già esistente, prendendo solo gli elementi che mi erano utili ai fini della trama, per poi stravolgerlo. Infatti, la narrazione originale si interrompe nel momento in cui il mio personaggio viene catapultato nel mondo di Grand Theft Auto V, deludendo scena dopo scena la promessa di un’avventura fantastica nel Paese delle Meraviglie. Creare una tale discrepanza mi è stato utile per evocare un’atmosfera tesa e snervante nello spettatore e guidare in un certo senso le emozioni e le riflessioni che intendevo suscitare attraverso il machinima. In The Rabbit Hole, infatti, ho deciso di allontanarmi dal racconto letterario originale tanto quanto dal testo videoludico stesso, eliminando da quest’ultimo l’azione e i ritmi frenetici, riprendendo ambientazioni vuote e silenziose, utilizzando spesso lunghe riprese a camera fissa. Ispirandomi largamente ai machinima di Phil Solomon e alla sua poetica, al cinema di registi come Ruben Ostlund e Gus Van Sant (in particolare il suo film Last Days, di cui cito anche la scena iniziale nel mio video), ho voluto imprimere nel mio machinima un’impronta che prediligesse l’osservazione e l’evocazione di precisi sentimenti, piuttosto che la ricerca dell’azione o la costruzione di una trama avvincente. In questo modo ho potuto parlare di crescita, delusione, alienazione, voglia di fuga dalla realtà, amicizia, solitudine e violenza senza il bisogno di seguire una trama incalzante.

Matteo Bittanti: The Rabbit Hole combina due differenti machinima: The Sims e Grand Theft Auto, probabilmente i videogiochi più utilizzati per creare narrazioni audiovisive non-interattive. In entrambi i casi, i rispettivi sviluppatori hanno incentivato la creazione di machinima inserendo tool ed editor direttamente nei videogiochi. Tuttavia, questa agevolazione rappresenta l’eccezione rispetto alla norma. Oggi infatti gli sviluppatori sembrano aver privilegiato la logica del photo mode e dunque della fotoludica rispetto a quella del movie editor nei videogiochi più recenti, e dunque del machinima. Come spieghi questo cambio di paradigma? Perché oggi il videogioco enfatizza l’immagine fissa anziché quella in movimento?

Kelly Rabbachin: A mio parere, gli sviluppatori preferiscono non inserire tool per la registrazione video perchè sono consapevoli che programmi esterni sono più performanti: se prendiamo come esempio il tool di registrazione video integrato in The Sims 4, notiamo che il video che ne risulta non ha la stessa qualità di immagine del gameplay effettivo. È molto più semplice e performante utilizzare programmi esterni ottimizzati per la registrazione di sessioni di gioco come ad esempio OBS Studio o strumenti come Xbox Game Bar di Windows; questo per quanto riguarda gli utenti che giocano ai videogiochi su PC, settore in costante crescita nel mondo del gaming degli ultimi anni. Questi programmi, rispetto a software integrati all’interno dei singoli titoli o delle console, possono effettuare registrazioni senza limiti di tempo, con il vantaggio di pesare meno sul carico di lavoro del processore. Inoltre, la maggior parte dell’utenza che gioca ai videogiochi, non è così interessata alla registrazione di sessioni di gioco, rendendo nella maggioranza dei casi questi tool ridondanti; fanno eccezione gli strumenti di registrazione replay, ovvero quei tool che registrano gli attimi immediatamenti precedenti a una certa azione di gioco, che vengono utilizzati dai videogiocatori per memorizzare eventi particolarmente eclatanti e magari condividerli sui social media. Quindi credo che gli sviluppatori — sempre più attenti alle richieste e all’opinione dell’utenza — siano consapevoli che strumenti di registrazione esterni sono più immediati e performanti di quelli che integrano i videogiochi o le console, hanno appreso che i software esterni sono facilmente accessibili a utenti capaci che vogliano creare contenuti relativi al gaming. Il Rockstar Editor di Grand Theft Auto V è un’eccezione da questo punto di vista: questo perchè permette, una volta registrata la sessione di gioco interessata, di applicare effetti, cambiare inquadrature, montare differenti sequenze assieme, utilizzando le funzioni di un editor video standard. Inoltre, la stessa Rockstar mette a disposizione uno spazio ad hoc per la pubblicazione dei filmati creati con il Rockstar Editor, incentivando la creazione di contenuti di questo tipo. L’immensità della mappa di gioco e le differenti ambientazioni, la cura grafica degli elementi visivi, la natura di gioco open world, rendono Grand Theft Auto V il terreno perfetto dove ambientare machinima e sperimentare con il video editing di sequenze videoludiche, e probabilmente Rockstar lo sa. Non credo quindi che gli sviluppatori vogliano disincentivare la registrazione video dei videogiochi in favore di strumenti di cattura immagine: semplicemente inserire uno strumento che consenta di fare uno screenshot alla schermata di gioco sia molto più semplice e meno invasivo che non implementarne uno per la registrazione video, che in molti casi verrà snobbato in favore di un programma esterno, nella maggioranza dei casi più flessibile e potente.

Matteo Bittanti: Qual è la percezione del machinima all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Milano? Secondo te esiste una comunità del machinima d’avanguardia in Italia?

Kelly Rabbachin: Ricordo che quando ho iniziato a proporre il machinima come argomento di tesi ai vari professori, nessuno sapeva effettivamente che cosa fosse. Mi sono vista più volte rifiutare il progetto per questo motivo, oppure è stato snobbato per l’apparente mancanza di valore artistico: “roba da nerd”, insomma. Mi aspettavo un responso del genere, in quanto i videogiochi in generale non hanno ancora oggi un valore artistico al pari dei medium del passato come il cinema o la videoarte, per quanto riguarda un pubblico più maturo e conservatore. Per fortuna, ho poi trovato dei professori disposti a seguire il mio percorso di tesi, interessati a voler approfondire il machinima come nuovo medium sperimentale. D’altra parte il machinima è effettivamente una nuova tecnologia dell’arte. Solo dopo ricerche approfondite, sono venuta a conoscenza del lavoro artistico di Marco Cadioli, professore all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Brera, che ha realizzato diversi machinima durante la sua carriera artistica, incentrata sulla realizzazione di opere di digital art. Questo mi ha fatto capire come il machinima sia effettivamente ancora legato ad una nicchia di utenti ed artisti molto ristretta, ancora non è stato legittimato come medium autonomo, dotato del proprio statuto, ma è ancora troppo spesso fatto rientrare nel macrogruppo della videoarte e della net art: per questo non credo esista oggi una community italiana legata unicamente al machinima. Esistono dei piccoli spazi di aggregazione all’interno di piattaforme più grandi, che uniscono però utenti da tutto il mondo: sto parlando, per esempio, del subreddit r/Machinima, dove utenti da tutto il mondo caricano i loro filmati, utilizzando il network come vetrina per i loro lavori. Siamo però infinitamente lontani dal defunto network Machinima.com, che grazie all’enorme successo che aveva riscosso grazie al canale YouTube, aveva fatto scoprire a milioni di utenti, principalmente americani, cosa fosse il machinima. A mio parere, il machinima è in una fase stagnante: vediamo troppo spesso machinima cosiddetti “del vernacolare”, ovvero che offrono sì narrazioni differenti rispetto al racconto originale, ma che finiscono però sempre per avere riferimenti al mondo videoludico nei quali è ambientata la narrazione. Questo non è un male: i videogiochi sono ora più che mai protagonisti della popular culture e hanno, in molti casi, maggiore successo del cinema, ma per emergere e legittimare questa pratica dovrebbe elevarsi a tematiche meno comiche e citazionistiche, sperimentare nuovi linguaggi e narrazioni, che vadano al di là sia del videogioco che del cinema.

THE RABBIT HOLE

machinima/digital video (1920 x 1080), color, sound, 9’ 50”, 2021, Italy

Director, Writer, Producer: Kelly Rabbachin

Sound: Flanagan & Allen, “Run Rabbit Run”, 1932

Made with The Sims 4 (Electronic Arts, 2014) and Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013)