For the best viewing experience, we recommend watching the video in full screen mode.

Platform

digital video (1920 x 1080, Arri Alexa), color, sound, 16’ 20”, color, sound, 2021, Germany.

Created by Steffen Köhn

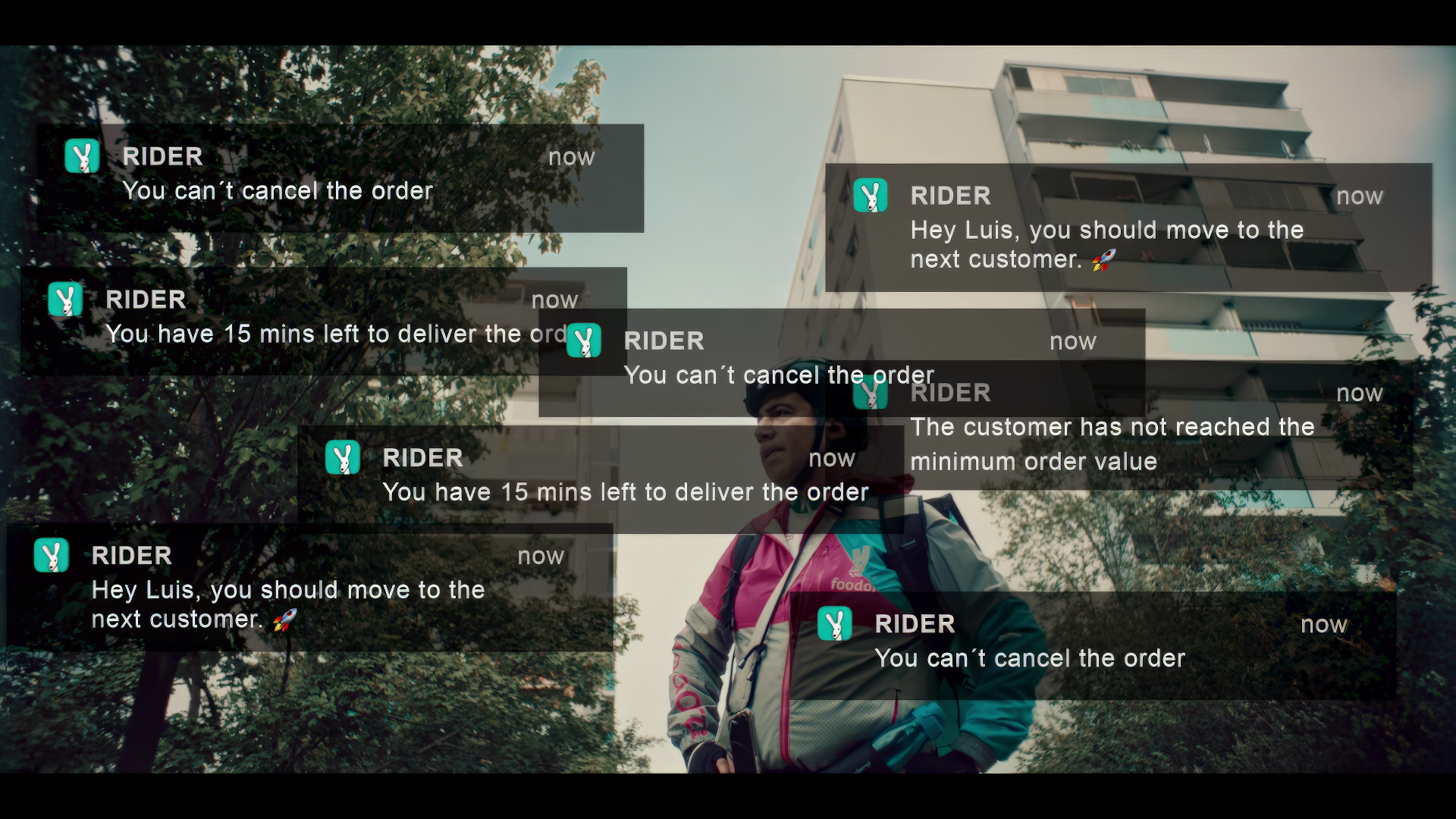

Platform draws from documentary interviews with freelancers on online delivery platforms, weaving their real-life experiences with elements from Neal Stephenson’s seminal 1992 cyberpunk novel, Snow Crash, which has gained iconic status in Silicon Valley. The film examines how the dystopian capitalist visions depicted in the novel mirror current capitalist dynamics. The narrative seamlessly blends the true stories of the research participants with fictional scenarios inspired by Snow Crash, creating a cyclical storyline that blurs the lines between documentary and fantasy. This technique plunges viewers into the complexities and paradoxes of modern work environments. Departing from traditional documentary styles, the film stages the drivers’ stories within a sci-fi framework, portraying their daily work struggles, prerogatives, and aspirations. Platform utilizes machinima to juxtapose live-action footage with video game based animations. This stylistic choice not only highlights the fading distinction between work and leisure but also prompts a deeper reflection on immaterial labor and value creation in today’s digital economy.

Steffen Köhn is a filmmaker, video artist, and assistant professor of multimodal anthropology at Aarhus University. He utilizes ethnography to delve into contemporary socio-technical landscapes. Köhn is the author of Mediating Mobility. Visual Anthropology in the Age of Migration (Wallflower Press, 2016). In his video and installation works, Köhn collaborates locally with gig workers, software developers, and science fiction writers to probe alternative models of technological access and power distribution. His works have been exhibited at prestigious venues including the Warsaw Biennial, Academy of the Arts Berlin, Kunsthaus Graz, Vienna Art Week, Hong Gah Museum Taipei, Lulea Biennial, The Photographers’ Gallery, and the ethnographic museums of Copenhagen and Dresden. Additionally, his films have been featured at major international festivals such as the Berlinale, Rotterdam International Film Festival, and the World Film Festival Montreal.

Matteo Bittanti: In developing Platform, you integrated video game graphics to craft an additional narrative layer. Could you discuss your collaboration with Alexander Bley? What motivated the initial choice to use machinima as a storytelling method, and how do you think it enhances the film’s depiction of the gig economy? Additionally, are you planning to further explore this medium in upcoming projects?

Steffen Köhn: The idea to mix machinima and real-life footage emerged early on in the project as we were very interested in the gamification aspect that all major gig-working platforms employ. In the course of our research, it became clear to us how much the operators of these platforms use aesthetic and organizational elements from the world of computer games to make repetitive work feel like a big competitive game. Such gamification elements can already be found in the design of the Uber or Deliveroo Rider app, which represents the riders with a small car or bike icon on a city map on which they then have to fulfill various orders. With the Amazon Flex app, the work shifts are offered to all riders at the same time and only the rider who accepts the job first by swiping gets the job. This is why the workers have developed “ninja-swiping” techniques in which they hold their smartphone like a game controller to accept shifts as quickly as possible.

Matteo Bittanti: Your observations echo the themes explored in Sarah Mason’s perceptive essay for LOGIC magazine, Chasing the Pink, where she recounts her experiences with Lyft. In her narrative, gamification emerges as a dystopian force, transforming seemingly harmless interactions into something far more ominous and oppressive. It’s ironic that several influential game designers were among the biggest proponents of gamification back in the day… For instance, Jane McGonigal depicted games primarily as tools or instruments to accomplish specific goals, rather than valuing them for their inherent qualities. This utilitarian approach underscores a troubling trend where the playful elements of gaming are harnessed to advance a hyper-capitalist agenda, imbuing the practice with a deeply opportunistic and cynical undertone, masqueraded under the same, empty Silicon Valley rhetoric about “changing the world” through technology. Ian Bogost famously dismissed gamification as bullshit, yet Byung-Chul Han offered a more nuanced perspective, aptly describing it as an insidious and pervasive ideology…

Steffen Köhn: …And yet while work is becoming more and more like a computer game, more and more computer games that simulate boring and repetitive tasks are coming onto the market. For many years, games like Euro Truck Simulator or Railway Construction Simulator were among the best-selling computer games. A mutual overlapping of work and play that we found fascinating.

Matteo Bittanti: Indeed. Are you familiar with Enjoying It: Candy Crush and Capitalism? His author, Alfie Bown, suggests that leisure activities, including playing games, are not just forms of rest or escape. Instead, they become another form of labor. Games demand time, attention, and often money, transforming leisure into an activity that has productivity and consumption values akin to work. According to Bown, digital games are especially effective at conditioning individuals to accept a work-like routine in their leisure, reinforcing and naturalizing the capitalist ethos of continuous productivity and achievement. This makes the capitalist work ethic pervasive, extending even into how individuals spend their free time, as Adorno and Horkheimer advanced in the 1940s. This phenomenon is prevalent in both compulsively addictive games like Candy Crush, which distract us from the mundane realities of many 'real' jobs we voluntarily undertake, and in games like Football Manager, which offer compensatory rewards, effectively an alternative career and thus an alternative identity—for those mired in what David Graeber defines as bullshit jobs. Far from merely providing escapist fantasies, digital games are intricately woven into capitalist structures. How, then, does machinima integrate into this dynamic?

Steffen Köhn: Machinima is also very much related to what is called “fan labor.” The makers of these films usually share their work online in the fan communities of a particular game, and the rights holders increasingly see this “labor of love” as a free and highly effective marketing tool. Thus, we hope that Platform not only explores the increasingly blurred boundary between work and leisure but also raises broader questions about the transformation of labor and value in the digital realm. As for the collaboration with Alexander Bley, he is a very experienced gamer and he came up with the idea of “modding” games like GTA V to create the cyberpunk world we wanted to portray. All the glitches he had to fight with in the modding of the game finally resulted in the last scene of the film… An idea we didn’t yet have when we were writing the screenplay.

Matteo Bittanti: When conceptualizing Platform, what were your primary inspirations beyond Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash? Were there other literary, cinematic, or academic influences that helped shape the film? The title itself suggests a connection to the academic field of platform studies, which examines the interplay between computing platforms and their cultural and societal impacts, focusing on both the technological and socio-economic dimension, themes your film directly addresses. I was wondering if you were familiar with non-fiction books like Platform Capitalism by Nick Srnicek, The Platform Society by José van Dijck, Thomas Poell, and Martijn de Waal, Platforms and Cultural Production by Brooke Erin Duffy and Thomas Poell? If so, how have these texts influenced your understanding and portrayal of platforms in your film?

Steffen Köhn: These books on platform operations were indeed a crucial source of inspiration that deepened our understanding of how these services function. However, our project truly began to take shape when Amazon, one of the most valuable companies in the world thanks to a business model that has engendered a new class of precarious delivery workers, invested $575 million in the food delivery company Deliveroo, aiming to eventually dominate this sector. Concurrently, Amazon’s entertainment division acquired rights to adapt Neal Stephenson’s Snow Crash into a TV series, a project that still appears to be stuck in development limbo. The irony was stark: the very company contributing to precarious working conditions now sought to dramatize these issues as entertainment. My fascination with the cyberpunk genre has been long-standing, dating back to my teenage years. The foresight of cyberpunk authors like William Gibson, Pat Cadigan, Bruce Sterling, and Stephenson, whose works are all set in the 2020s but were penned during the 1980s and 1990s, prompted us to question how much of their speculative futures have actually materialized. Today, the internet – or cyberspace, as envisioned by Gibson – has thoroughly infiltrated our daily lives, with virtual reality (Stephenson’s Metaverse) poised to merge even more deeply into our consciousness. The immense power of transnational corporations, the widening socioeconomic divides, and the dual-edged sword of artificial intelligence all very much reflect the dystopian elements these authors predicted.

Matteo Bittanti: I have seen a couple of terrific documentaries about the gig economy, including Shannon Walsh’s The Gig is Up (2021), which primarily utilize traditional documentary techniques. What inspired you to blend ethnography, political economy, sociology, and science fiction in Platform? How did you achieve these seamless transitions between documentary and fictional elements within the film? Could you share some of the significant challenges you faced when integrating documentary interviews with digital storytelling, and how you addressed them? Additionally, how does the depiction of drivers’ stories within sci-fi contexts enhance the portrayal of the darker realities of gig work, and what impact do you hope this hybrid approach has on the audience?

Steffen Köhn: As a visual and multimodal anthropologist, I have always been fascinated by documentary approaches that venture into the speculative and the imaginative, a filmmaker such as Jean Rouch would be an obvious example. When doing ethnographic fieldwork, I find it important to also account for people’s imaginative horizons. And I want to portray the world not only as it currently is, but also as it could be. I would even argue that this is one of the major strengths of anthropology: to show us that there are alternatives to the given. That people in different times and at other places have organized their affairs very differently, and thus that even the most ossified arrangements of power can be changed. During our interviews, many gig workers not only described their oppressing work conditions. They also shared their strategies to circumvent algorithmic control and discussed emerging forms of labor organization in this new work environment. Their stories, contrasting sharply with the broader narrative of technological dominance, added a profound layer to our understanding and inspired our approach to the film. Employing science fiction as the medium was a natural choice, aligning perfectly with our goal to faithfully represent these insights. In the end, the film tilted more toward fiction than documentary. Initially, we aimed to cast real drivers for the roles and conducted several casting sessions, but we ultimately chose mostly professional actors – though several had personal experience with gig work or precarious employment. Nevertheless, our screenwriting process was deeply influenced by what we learned during our interviews

Matteo Bittanti: I read somewhere that “dystopian fiction is when you take things that happen in real life to marginalized populations and apply them to people with privilege”. What are some of the critical assumptions about the gig economy that you wanted to challenge or highlight through this film?

Steffen Köhn: I guess we wanted to give faces and stories to this mostly invisible workforce and show what strategies of resistance are possible within these highly surveilled work conditions.

Matteo Bittanti: Platform addresses themes of accelerationism, techno-optimism, and the Californian Ideology, which essentially views technology as a religion in Silicon Valley. This theme recur in another recent machinima using Cyberpunk 2077, Andy Hughes’ Inner Migration. How do you perceive these ideologies influencing the future of work and technology, particularly in the context of the narratives you’ve depicted?

Steffen Köhn: I believe these ideologies, which continue to influence many Silicon Valley business ventures and have taken an even darker turn in the apocalyptic escape fantasies of tech billionaires that Douglas Rushkoff documents in Survival of the Richest, have been extensively critiqued in recent scholarly and artistic works. I concur with these analyses. While I do not subscribe to accelerationism’s social and political agendas, I do see its value as an aesthetic framework. The traditional aesthetics of critical distance and analysis, in my view, no longer effectively address our deep entanglement with the algorithmic overkill of late capitalism. That’s why we wanted to tell our story at a speed that keeps up with the current social media-driven attention economy.

Matteo Bittanti: FLEXPLOITATION, another collaboration with Johannes Büttner, merges sculptural installation with a literary event series at Literaturhaus Berlin, embodying a monstrous drive-in cinema. This installation not only serves as a viewing environment for Platform, but also as a forum for readings, video screenings, and discussions. Could you elaborate on how the physical design of the installation and the choice of activities contribute to the exploration of themes such as algorithmic management, shifting forms of value creation, and new social organizations in the digital economy?

Steffen Köhn: An integral component of Platform is its unique screening environment – a sculptural spatial installation designed to draw viewers even deeper into the video. The seating is crafted from parts of a plaster cast of a car wreck, which we modified to emphasize futuristic elements: the engine protrudes from the hood and the dashboard is augmented with additional levers, switches, and buttons. Instead of traditional car seats, viewers sit in gaming chairs – used by professional gamers – evoking the feel of racing car seats and we even installed “body shaker” – speakers under the seat so they vibrate with the bass of the sound design and the score. Besides maximizing immersion and underscoring the work’s cyberpunk themes, this installation again alludes to the “fan labor” around Snow Crash as the design draws inspiration from fan art and forums like DeviantArt, where enthusiasts reimagine the delivery vehicle from the novel, as well as films like Mad Max that depict a dystopian future of societal breakdown and survival struggles. We also used the space, however, as a dynamic public forum during the exhibition. This allowed us to engage with workers, grassroots unionists, writers, and social scientists in regular lectures and discussions about the future of work in digital platform capitalism. Our goal was to broaden public engagement and address current political and social issues beyond traditional art discourse, turning our sculptural installation into a platform for debate that fosters common interests in our increasingly fragmented public sphere.

Matteo Bittanti: Your project PakeTown (2021) is an ethnographic mobile game that documents and simulates the operations of El Paquete Semanal, an offline, informal media distribution network in Cuba that circulates digital content like movies, TV shows, music, and games through physical media such as USB drives and hard disks due to limited internet access. PakeTown not only reflects on the media distribution but also invites players to engage actively and directly with the material, and is somehow complementary to your expanded cinema project Memoria. Could you elaborate on the challenges and insights gained from integrating real biographical interviews with paqueteros into the game’s development? Additionally, both Platform and PakeTown integrate digital technologies into their storytelling to explore economic realities within specific cultural contexts. Could you discuss how the choice of medium – that is, film and machinima for Platform and interactivity for PakeTown – affects the way audiences perceive and engage with the socio-economic themes you are presenting?

Steffen Köhn: PakeTown is an ethnographic video game that I developed together with Cuban media artist Nestor Siré. It delves into the history of Cuba’s unofficial media circulation networks, a theme that I have been exploring as an anthropologist through long-term ethnographic fieldwork for many years. Spanning five decades, the game invites players to experience the evolution of the informal Cuban media sector in the format of a business simulation game. Players step into the shoes of small entrepreneurs who run illicit media rental stores from their homes. They must also efficiently manage their resources by paying attention to the inventory of products, the provision of new content and the maintenance and updating of equipment. I have also produced more traditional ethnographic research articles about my research into Cuban offline practices but at some point, I wanted to create something that would be meaningful first of all for a local audience, which is why I turned to interactive gaming. Conceptually and aesthetically, PakeTown is therefore inspired by the genre of tycoon games such as Pizza Syndicate, FarmVille, and Resort Tycoon, which enjoy immense popularity among El Paquete Semanal consumers across the island.

Matteo Bittanti: Could you elaborate on the development process of PakeTown? How did you circumvent political as well as technological constraints imposed on Cuba by the US?

Steffen Köhn: The game was developed by ConWiro, one of the island’s pioneering independent game studios. The team at ConWiro consists of several programmers who honed their skills as members of Havana’s grassroots community computer network SNET (Street Network) and therefore have a natural connection to the game’s content and subject matter. Collaborating with them provided invaluable insights into how they overcome the complex technological and political constraints on the island. Therefore it became a kind of research strategy in itself. As the economic embargo imposed by the United States limits Cubans’ access to Google Play and Apple App Store, we made PakeTown freely available on the island via Apklis, the national app store run by the state. It was further distributed through El Paquete Semanal, the very medium it portrays. So compared to Platform, which is maybe a more associative, artistic rendering of its subject matter, PakeTown was meant as an intervention into the local context. We organized several public presentations in Cuba and even organized a tournament to find our local audiences.

Platform

digital video (1920 x 1080, Arri Alexa), color, sound, 16’ 20”, color, sound, 2021, Germany.

Cast

Roberto Anjari Rossi

Kumar Muniandy

Boris Dikelo

Tyrone Raymond

Yasmin El Yassini

Jan Koslowski

Lola Abrera

Crew

Director: Steffen Köhn and Johannes Büttner

Screenwriter: Steffen Köhn and Johannes Büttner

Director of Photography: Patrick Jasmim, Phillip Kaminiak

Editor: Gines Olivares

3D Artist & VFX Supervision: Alexander Bley

Producer: Paola Calvo, Patrick Jasim, Phillip Kaminiak

Music: Johannes Klingebiel

Sound Design: Lorenz Fischer

Made with Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013)