Rapid Transit: Preface

digital video, color, sound, 13’, 2020, Venezuela/USA

Created by Victor Morales. Music: Daniel Dobson. Voices: Modesto Jimenez and Christine Schisano. Written by William Burns.

World premiere

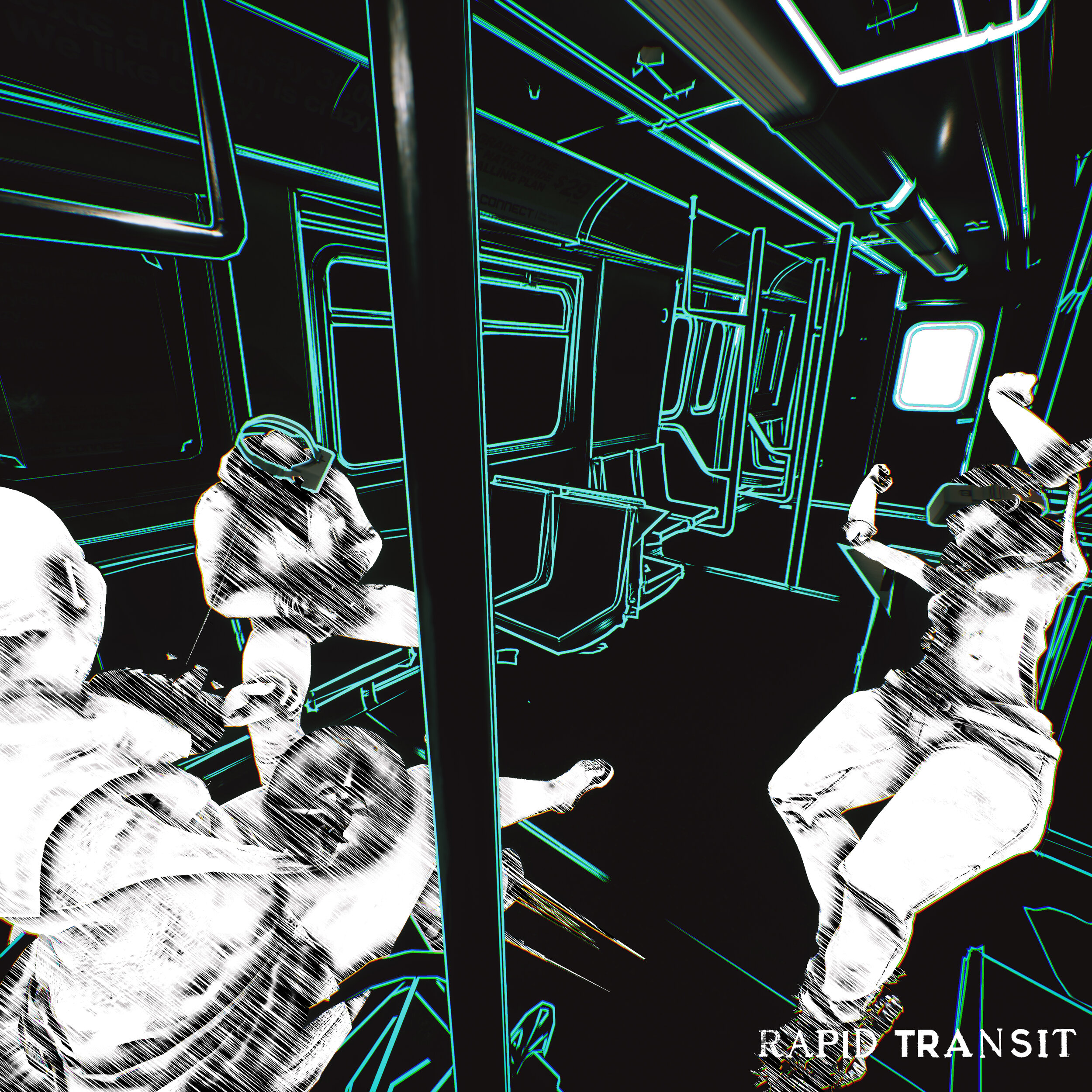

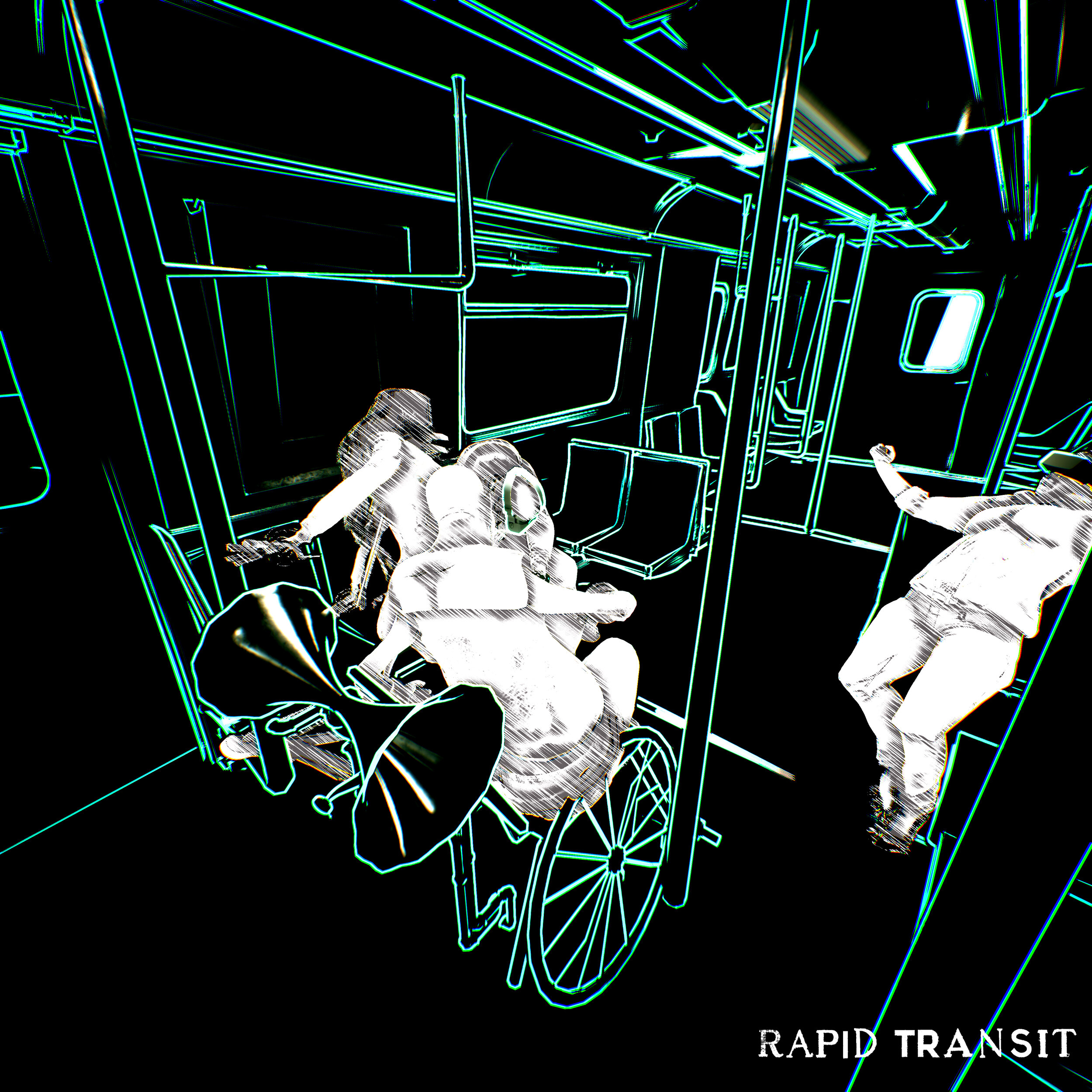

What is it like to ride the New York City subway thirty years from now? Victor Morales predicts that most travellers will wear VR/AR displays combined with electric stimulants or lectrics. But the subway itself has not changed much nor its rituals: passengers ignore each other while dancers perform to rhythmless soundtracks interrupted by beeps and synthetic shouts popping out of devices like rings and bracelets featuring holograms with hovering capabilities. On a late weekday night, a rider under the influence boards the train, unbeknownst to what is about to happen.

Born in Venezuela and based in New York City since 1991, Victor Morales is a director, performer, and designer. His practice includes theater direction, video design, animation, text, sound design, and digital puppetry. He collaborated on a variety of projects with Chris Kondek (Berlin), Joseph Silovsky (NYC), Jim Findlay (NYC), Findlay/Sandsmark (Norway), and Wolfgang Mitterer (Austria). Since the early aughts, Victor has been using video game engines to create interactive and non-interactive artworks. His multidisciplinary project Esperpento was selected for the Sundance 2019 New Frontier program and received the “Best Immersive and Time Based Art” award at the B3 Biennial at the Buchmesse in Frankfurt, Germany.

Matteo Bittanti: After virtually resurrecting Francisco Goya with Esperpento, you returned to New York and took us for a ride on a near-future subway system that looks suspiciously similar to our own. How did Rapid Transit: Preface come to be?

Victor Morales: Rapid Transit started out of my interest in science fiction. I wanted to work on something about the future, but predicting changes in technology, culture and behavior is never easy. So I decided to do something without indulging in mad speculation. Since the beginning, I knew that it had to be about the near future, not one hundred years from now, but maybe thirty years or so. One day, while I was on the subway, I realized that I have been riding these cars for approximately the same amount of time, since the early Nineties. In that time frame, the subway has not changed much. The cars are a bit more modern and people have replaced their walkmans for smartphones, but they’re still in their bubbles. I can imagine the future thirty years from now by looking at the past three decades of this very controlled environment. This is a space that reflects the inequalities and kinks of the city, shuffling its people around. I am also very intrigued by the challenge of telling stories inside the subway, a fragmented, almost anti-social place. The full project, Rapid Transit, is still being developed as we speak.

Matteo Bittanti: What is the relationship between Rapid Transit: Preface and the larger project? Was Rapid Transit originally conceived as a large-scale, interactive projection platform featuring immersive installations and VR technology, like Esperpento? If so, what should we expect next?

Victor Morales: I started working on Rapid Transit last summer. I played with looks, re-hashed some mocap files from Esperpento and previous projects, then wrote a script and a description of New York City in 2050. I also produced a lot of video screen captures and hours of live streaming. Preface is the outcome of these experiments, or rather a Frankenstein-like monster byproduct of those early explorations. Rapid Transit is a VR multi-user art installation: A “ride” is experienced by five or six people simultaneously inside a subway set. The “players” can see each other as avatars, “passively possess” the main characters featured in each ride. Up until now I have worked with a very small team: Modesto Jimenez (writer) and Daniel Dobson (musician) are my core collaborators for the project. I am in the process of finding funds to expand the team and create one of the six rides this summer.

Matteo Bittanti: What were the most difficult challenges that you faced while making Rapid Transit: Preface?

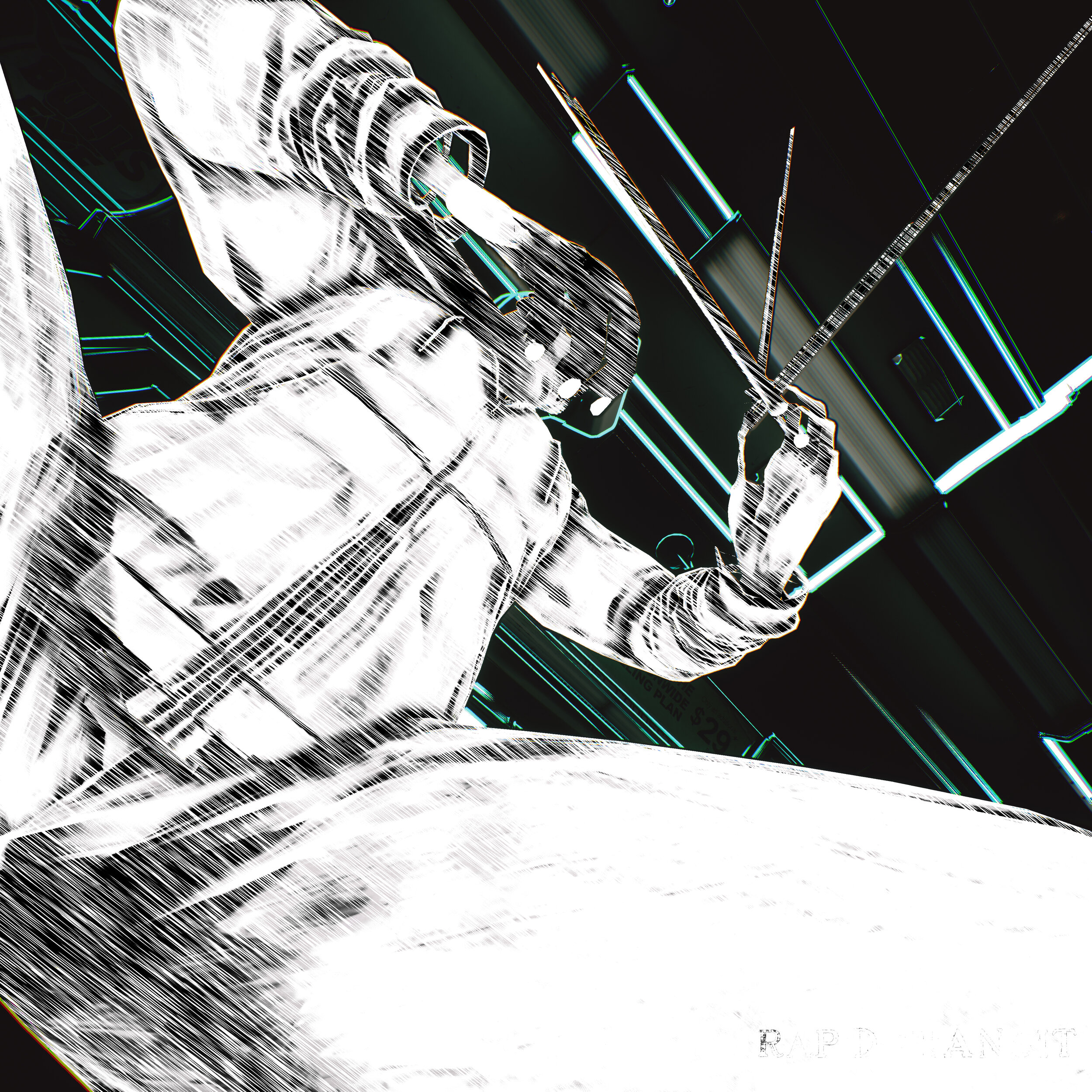

Victor Morales: After many years working with video game engines, I have developed a process, a pipeline, a practice where the main goal is not to aim at a preconceived image or idea but to actively look for it. I do not use storyboards and the script is always evolving. I generally run a series of improvisations around POVs, text, movement and/or a sound. Rapid Transit: Preface – like most of my work – is not rendered frame by frame, like an animated movie. It is played or, rather, puppeteered in real time while the screen is captured. We shoot many takes and control/change different variables like sound, animation, camera angles and movements, by using MIDI controllers, gamepads and mocap systems. Then, after stitching the things we like, we produce a little movie like Rapid Transit: Preface.

Matteo Bittanti: You’ve been working with video game engines for almost two decades now. How did they change? What is still missing, if anything?

Victor Morales: Fifteen years ago, the only way to work with these engines required hacking the actual video game and/or using the modification tools of games like Far-Cry, the first two episodes of Half-Life, and Warcraft III. Back then, I spent a lot of time just on the hacking side of things; always adapting the game assets to the project and, vice versa, adapting the project to the assets. My process is an outcome of such history. I am still re-hashing, mixing, “doing things the wrong way”, finding interesting glitches and “making” meaning while “stitching” like a modern day Dr. Frankenstein.

Today we have Unreal Engine 4, Unity, Cry Engine and many other kinds of software which are basically full tool-sets for the creation of video games. This is way more democratic: anyone could spend some time learning these tools and make a piece of interactive art, a video game, a machinima, a full blown animated movie, without having to invest so much in figuring out how to move a virtual camera or how to extract an animation. Today, there are marketplaces for assets and almost all the 3D software can easily export assets to these engines. That said, I do not think these engines are easy to master, but compared to fifteen years ago, the process has become much more intuitive, and artists have almost total creative freedom.

Matteo Bittanti: In Preface, the characters are floating in space, like astronauts on a spaceship. Are you suggesting that the passengers are somehow unhinged, as if any sense of personal balance has been replaced by a spatial uncertainty that may reflect broader societal displacement?

Victor Morales: Being in the subway, in transit, is a kind of dead time. People do not want to be in the subway. Thirty years ago people used to hide their faces in books or in the Village Voice. Today we hide ours in smartphones. Most people displace themselves on the subway, ignoring fellow travellers, just waiting to get out at their stop. The subway is a metaphor for social displacement.

Matteo Bittanti: In the second segment, a female character is struggling to breath in a quasi-empty wagon. We hear her coughing repeatedly and although we are physically removed from the scene, it is hard not to feel a sense of uneasiness and anxiety. Is this the new normal? What’s going to happen to public transportation in the age of social distancing?

Victor Morales: The other day I rode the subway - it was the beginning of this year’s lockdown in New York City - for research purposes, so to speak: it was almost empty. The few “passengers” were scared, myself included, all wearing masks and gloves, not knowing how to deal with this new etiquette. I hope this won’t become the new normal, but it may as well be for the foreseeable future.

Matteo Bittanti: In the future that you imagine, most passengers on the subway are wearing VR displays, their own filter bubbles protruding from the face. Do you expect that this technology will ever catch on in public spaces and become pervasive like the walkman in the 1980s and AirPods today?

Victor Morales: In theory, smartphones will be replaced by wearables within the next two decades. The script of Rapid Transit mentions BandanaX, an innovative new company, like Google twenty years ago, which produces a kind of cloth-based XR system that can do everything a smartphone can offer, plus public privacy while wearing it over your face. And considering what’s going on these days, it is likely that the BandanaX in Rapid Transit will also offer some kind of health protection. Fact is: our reality is way harsher than the fiction I imagined. In Rapid Transit: Preface, BandanaXs are the VR goggles; they act like Frankenstein-like pieces posing as BandanaXs.

Matteo Bittanti: Most of the characters that we encounter in Preface are ranting, repeating the same sentences as if they were stuck in a loop. If language is a virus, are communication acts comparable to glitches? If language is a virus, are communication acts comparable to glitches?

Victor Morales: These repetitions are also part of the process: the scenes are recorded live. The actor/avatar is in a loop, which is also the kind of repetitiveness typical of mental illness, which sadly, is a condition that abounds in the NYC subway.

Rapid Transit: Preface is a machinima, and in the true spirit of machinima, it demands imperfection. A kind of unfinished quality is its staple. I want to believe in a kind of beauty born out of the imperfect, the defective, the subnormal, the discriminated, the glitched.

One very important premise of this project is that the camera (the POV) is always filtered, and this means that the audience is seeing the scene through a XR system (BandanaX) that can affect the perception of reality like an hallucinogenic drug would do. That is another important feature of the BandanaXs: they are both an XR system and a therapeutic system, they can electro-stimulate the brain so the user can feel excitement/energy or relaxation or even hallucinate out of wearing them.

Matteo Bittanti: Any concluding thoughts?

Victor Morales: The history of art is as important as its future, techniques, motivations, and hallucinations of the past are key to understanding what is coming. Masters like Francisco Goya or George Clinton have already seen it and painted it, heard it and sang IT.

Rapid Transit: Preface, 2020

digital video (1920 x 1080), color, sound (stereo), 13’, 2020, Venezuela/USA

Created by Victor Morales, 2020

Courtesy of Victor Morales, 2020

Music: Daniel Dobson

Voices: Modesto Jimenez and Christine Schisano

Written by William Burns