Shadows:ULTRA

digital video (1500 x 1080p), color, sound, 09’ 30”, Germany

Created by Thomas Hawranke

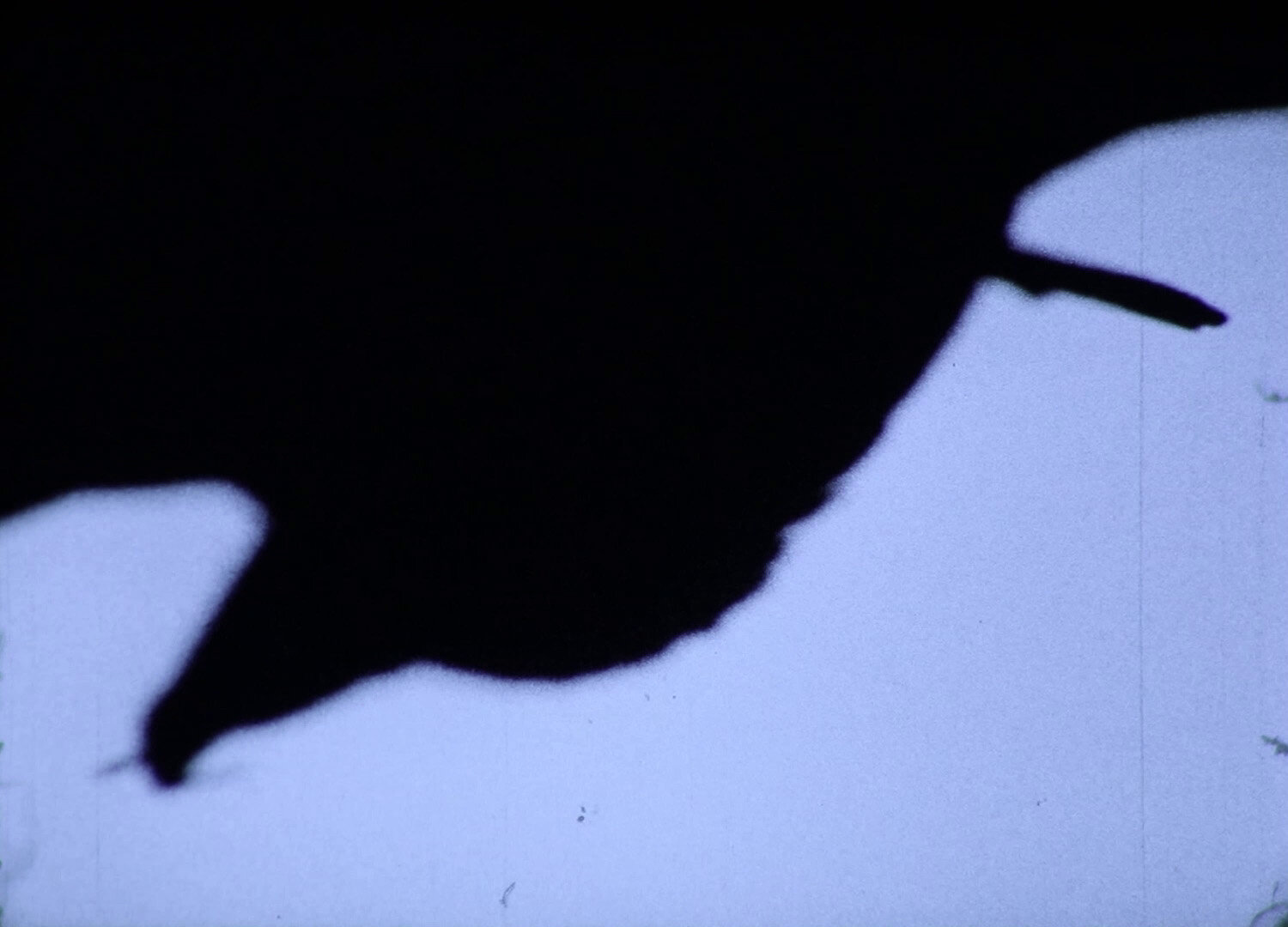

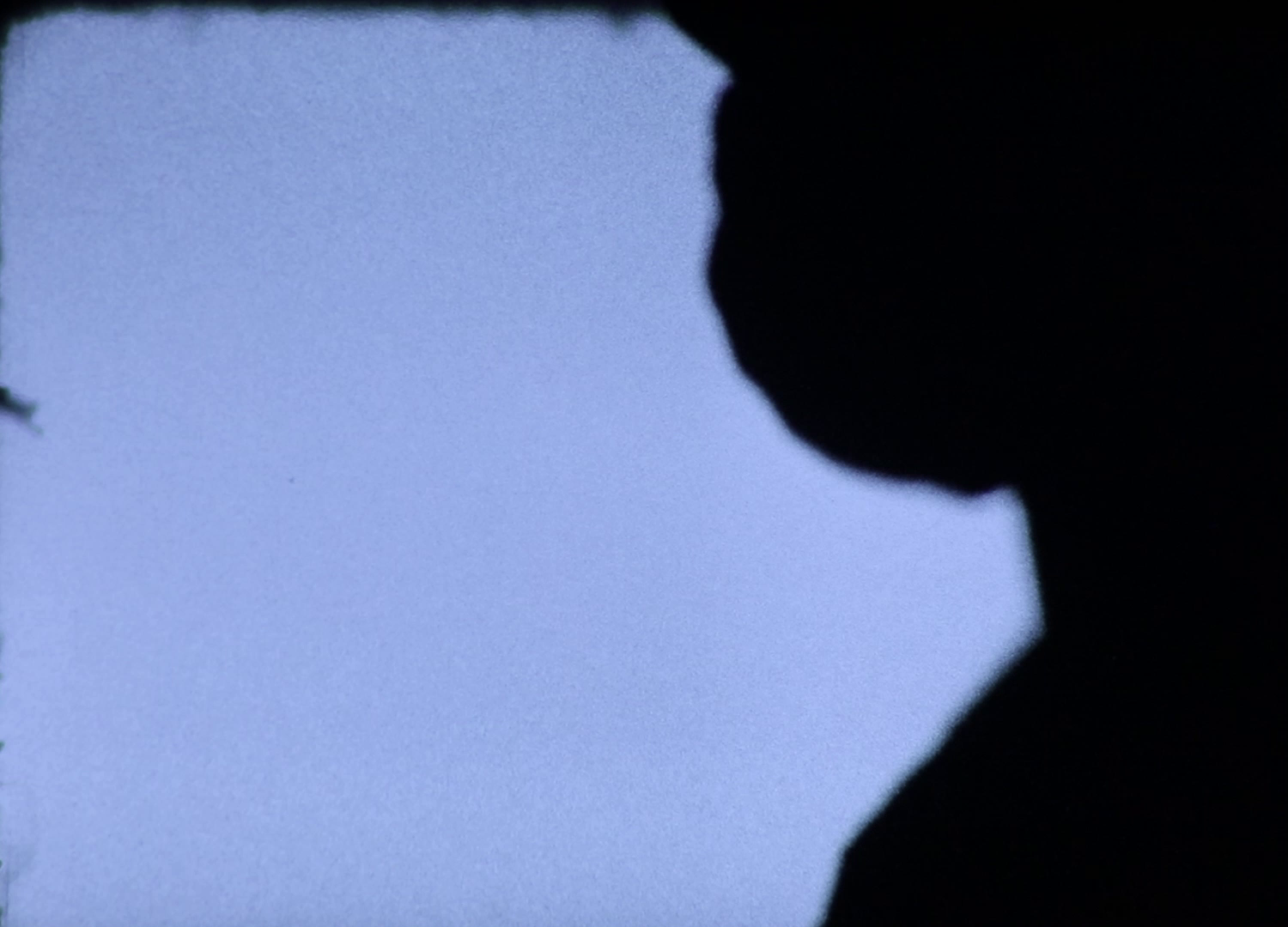

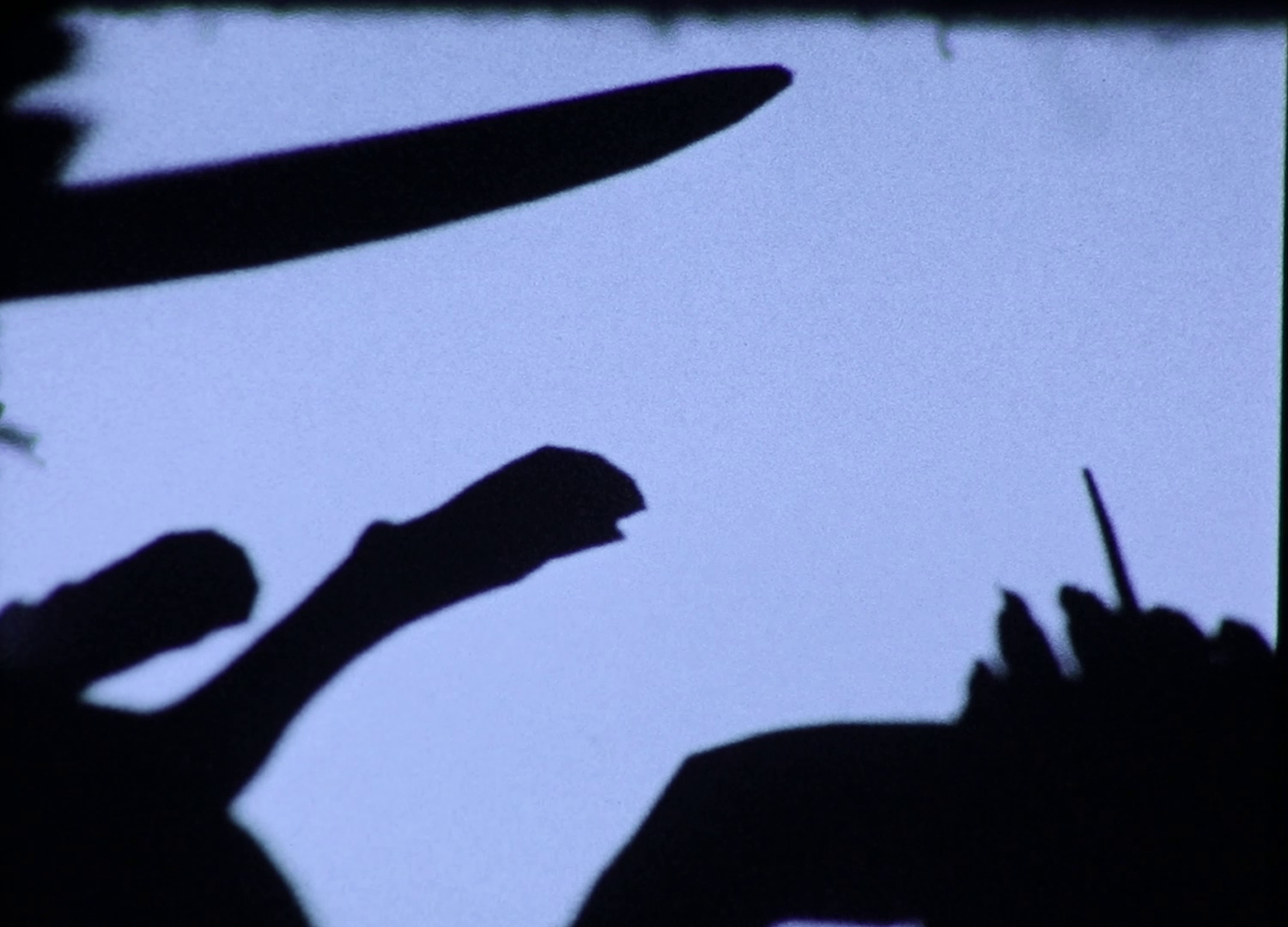

Shadows:ULTRA shows in different shots the overlapping animal shadows within the Dunia game engine, a software fork of CryEngine designed by Kirmaan Aboobaker while working at Crytek. Thomas Hawranke filmed the individual images from the monitor with a Kodak Tri-X 7266 eight millimeter camera, and subsequently exposed, cut, and again digitized the film material. The limited resolution of the shadow maps within the game engine is negated by the grain of the film material. The soundtrack was created by assembling various field recordings created in the late 1930s by Ludwig Koch, a musician and animal voice collector.

Born in 1977 in Bergisch Gladbach, Germany, Thomas Hawranke is a media artist and researcher whose practice focuses on the influence of technology on society and the impact of computational logic onto human relationships. In his projects, Hawranke operates at the intersection of performance and video art: one of his key concerns is bringing to light the ideologies underlying everyday life. Hawranke graduated in Media Art at the Academy of Media Arts Cologne and is currently finishing his practice-based PhD at the Bauhaus-University in Weimar, Germany, with a dissertation on the modification of video games, also known as modding, as a method for artistic research. Since 2005, he has been a member of Susigames, an independent art label founded in 2003 that investigates alternative gaming’s approaches, and he is the co-founder of the Paidia Institute in Cologne. His works have been presented at several exhibitions and festivals, including the Next Level Festival in Essen and the Weltkunstzimmer in Düsseldorf. Hawranke lives and works in Cologne, Germany.

Luca Miranda: I’m really fascinated by your creative process but also in some technical aspects. For example, why did you use the Dunia game engine to create this artwork? Is it because such a tool was specifically developed for games featuring complex “natural” environments, like Far Cry 2? On other words, was your choice primarily motivated by technical reasons, was it an homage to a specific work or something else altogether? Can you recall a particular episode, text, film, or artwork that inspired Shadows: ULTRA?

Thomas Hawranke: The Dunia Game Engine is based on the CryEngine that was sold to Ubisoft after the original Far Cry. At this time the CryEngine was known not for rendering dark, enclosed spaces but rather sunny open spaces, with a special focus on plants, trees, water, and other natural elements. Whereas the Unreal Engine worked by subtracting things from a mass, CryEngine used an additive method in building a simulated world. I am very interested in how the CryEngine simulates flora and fauna. In 2008 I built a level so that a plant with sensors could play against its virtual brothers and sisters.

In 2013 I focused on the AI system and its underlying codes. The CryEngine and I share a long history. Key reasons for using the CryEngine can be summarized as follows: as an artist, I could use such a tool for free. Moreover, Far Cry has a vast modding community. In other words, I chose this tool for three reasons: access, that is, it’s a free and readily available resource; use, as it focuses on the representation of plants and animals, and support, because it can rely on a flourishing online community with vast knowledge on tool creation.

Shadows:ULTRA was influenced by a variety of sources. First, the photography of animal locomotion by Eadweard Muybridge and a variety of videos about animal behavior from the Encyclopedia Cinematica. The sounds you hear are a collage of early animal field recordings conducted by Ludwig Koch for the BBC in 1938. When I created Shadows:ULTRA I also read The Play of Animals, written in 1896 by Karl Groos. I love each and everyone of these things and they have been a part of my life for quite some time.

Luca Miranda: You first experimented with 8mm shooting with 8mm Coyote Test. That work reminded me of the early films by the Lumière brothers. It also reminds me of the aesthetics of found footage. Are you deliberately referencing these sources in your films? Are you using the documentary format to investigate the tension between reality and virtuality? Is machinima, therefore, an inherently self-referential medium?

Thomas Hawranke: For 8mm Coyote Test I experimented a lot with analog technology. It is cranked by hand; the camera had some technical issues and the material was very old. I did a lot of testing with the time for exposure and with the chemical processing of the material. Then again I had some situations created within Far Cry, Grand Theft Auto V and within the CryEngine Editor that I wanted to test out with the analog material. This is definitely an investigation into both the analog and the digital. As I love found footage as a format – especially for machinima – this phase of experimentation was rather grounded. I tried to provoke different kinds of aesthetic effects from the material layer and to get a deeper understanding of the processes of transformation between the analog and the digital. For me, machinima is not necessarily self-referential, because it can often touch broader phenomena, like human-animal relationships, materiality of the digital, other media forms and their underlying philosophies, for example photography, video/film, sound etc.

Luca Miranda: Shadows:ULTRA reminded me of Ingrid Bergman’s Persona – specifically, the opening scene, which shows the inner working of a camera and old chinese lanterns. In your practice, the mechanic – here somehow ironically remediated through digital technology – becomes a crucial concern. Can you describe the genealogy of Shadows:ULTRA? Is this specific work a commentary on the materiality of media, their mechanical elements?

Thomas Hawranke: In my work, the interpretation of data by machines is important and this includes the underlying mechanical processes of these machines. I always try to reflect the inner life of the apparatus. It drives the order in which I show the content, it influences the rhythm of image sequences or the interplay between sound and video. I am a huge fan of Reynold Reynolds’ work because for me many of the things he shows are a meditation on mechanical processes that are mediated. I really love his camera work.

Luca Miranda: The juxtaposition of images and sounds engender a persistent atmosphere of eeriness. It is as if you are explicitly telling the viewer that what we are experiencing is not real but – at the same time – that it may as well be a record of some sort, a document. How do you construct such a peculiar relationship between what we see and what we hear in Shadows:ULTRA?

Thomas Hawranke: Shadows:ULTRA is part of an experimental practice, where in order to find out what could be the materiality of the virtual, media content is translated from the digital to the analog and back. Shadows:ULTRA tries to hide its digital origin through the analog process. This is achieved, for instance, by dropping the frame rate or by transforming compression artefacts to the grain of the analog film material. I really like the idea that we take some perfection of real-time away and that this reduction results in a more ‘realistic’ perception of what we see.

Luca Miranda: Mark Rothko once said: “It came a time when none of us was no longer capable of using a figure without mutilating it”. In the accompanying statement of a work of yours, you mention a kind of wilderness “domesticated by the programming code”. Non-human animals feature prominently in your practice, and such a theme is all the more striking considering our hypermediated society. I am thinking about Tiger PHASED and the code’s computational logic, but also about Grand Ape Town and Play as Animals where we witness two sides of Los Santos. How do video games represent non-human animals? How do anthropocentric notions inform the design of playful simulations? When did you first become aware of the underlying issues relating to this process?

Thomas Hawranke: I think that there is a long history for the representation of animals in video games, which derived from the animals shown on tv, cinema or photography. Animals can be anthropomorphic heroes, ferocious enemies and often just objects. They foster the idea of liveliness for the game environment and become part of the ornament. They are killed and they are played. Besides this representational aspect there are also many different ideas and concepts about the relationship between humans and animals created through game mechanics: Baiting, taming, bonding, breeding, etc. And of course gaming communities talk about these things, how for example being a vegetarian influences the interaction with in-game animals.

The starting point for me were scripts I found within CryEngine. They facilitate animal behavior, for example the movement of flocks of birds. Within those files I found notes from the programmers, in which aspects of animality were commented. This was the point where I understood that every design is tainted and that the idea of what animals are is part of a very complicated socio technical network between production and consumption of video games.

Luca Miranda: Somehow related: in your work, you often apply modding as a subversive practice to pursue gender-swapping and species-swapping, replacing male characters with female characters and human animal characters with non human animal characters, such as chimpanzees. Is it in such malleability – which is the outcome of an artistic intervention upon an otherwise stereotypical game – that the utopian potential of machinima ultimately lies? If not, what do modding and machinima represent, to you?

Thomas Hawranke: Modding is very important for both the industry and the community. When I create machinima, I also mod: both practices are entangled with each other.

To link this to the representational aspects of animals in my work I would say modding is not only a utopian practice but also a practice of resistance: As Espen Aarseth puts it, all these transgressive forms of interaction within video game space ultimately deal with the issue of reclaiming control over something that controls us so deeply*. When for example modding communities and the industry fight over copyright infringements, the community answers with machinima. These movies become an important tool for the protest and sometimes they are the protest.

When I mod a chimpanzee into GTA V it is not only an utopian fantasy that I want to show. It is about putting the animals into the center of the game; into the center of attention. Because we need to refocus on those who are at the margins of our shared world.

Luca Miranda: Video games are often a portal to bizarre universes. They allow us to experience weird situations and encounter otherworldly characters. Virtual worlds seem somehow related to the so-called beyond. What is your relationship with the strange, the weird, and the eerie?

Thomas Hawranke: I love it! To see something that is in a way not streamlined, that catches me by surprise and that challenges my way of thinking enriches me. Of course there is a huge variety of things you can witness and sometimes they are offensive. But in the end video games are such heterogeneous spaces that I found my way of dealing with that.

* “These marginal events and occurrences, these wondrous acts of transgression, are absolutely vital because they give us hope, true or false; they remind us that it is possible to regain control, however briefly, to dominate that which dominates us so completely.” [Aarseth, Espen J.: I Fought the Law: Transgressive Play and The Implied Player, in Digital Games Research Association (Hrsg.): Proceedings of DiGRA 2007 (p.133)]

Shadows:ULTRA

digital video (1500 x 1080), color, sound, 09’ 30”, Germany

shot on Kodak Tri-X 7266 (8mm), 18FPS. Scanned on 1920 x 1080, 25 FPS

Created by Thomas Hawranke, 2019

Courtesy of Thomas Hawranke, 2020

Made with Dunnia engine (Ubisoft, 2008-)