Chain-link

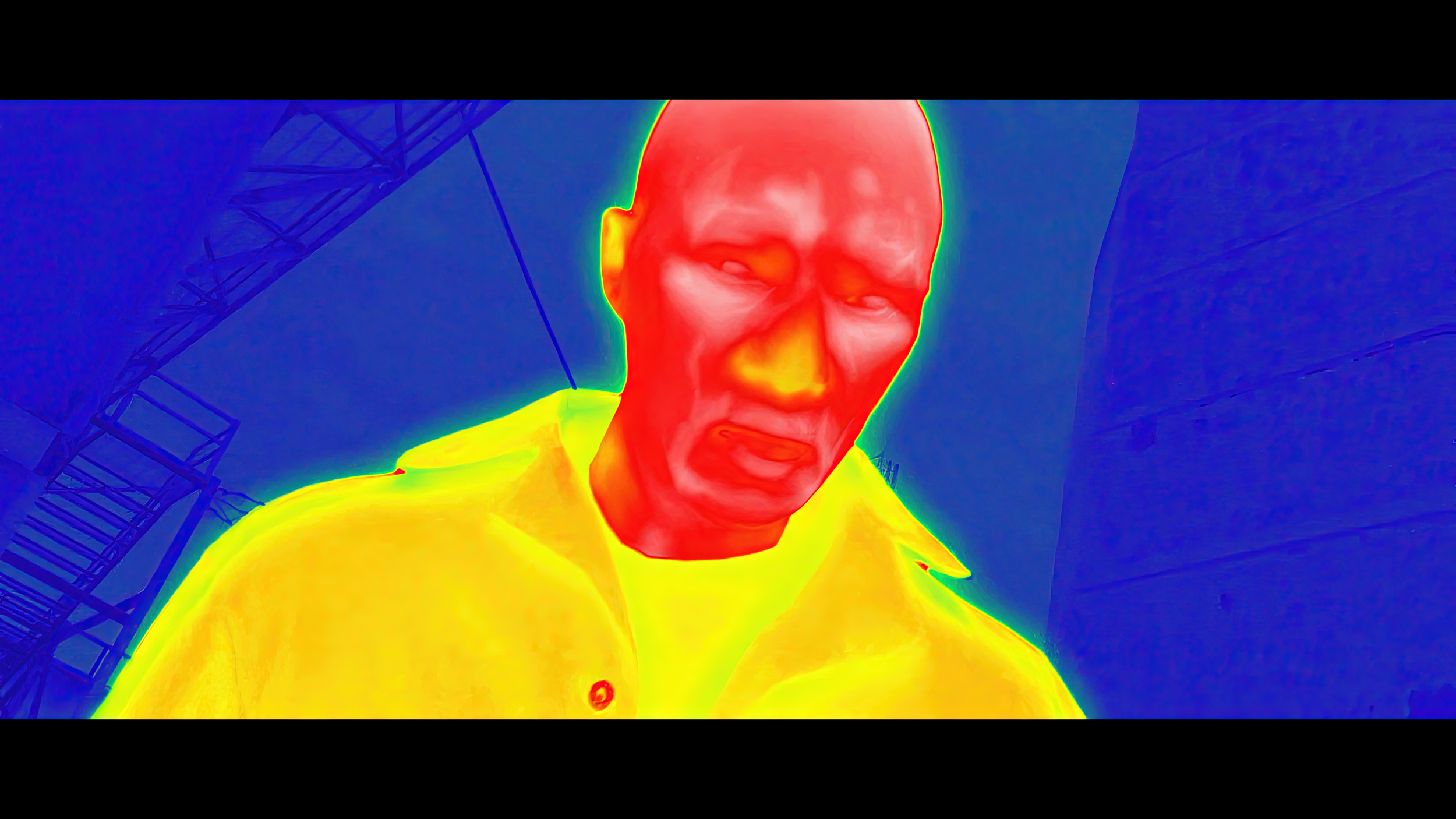

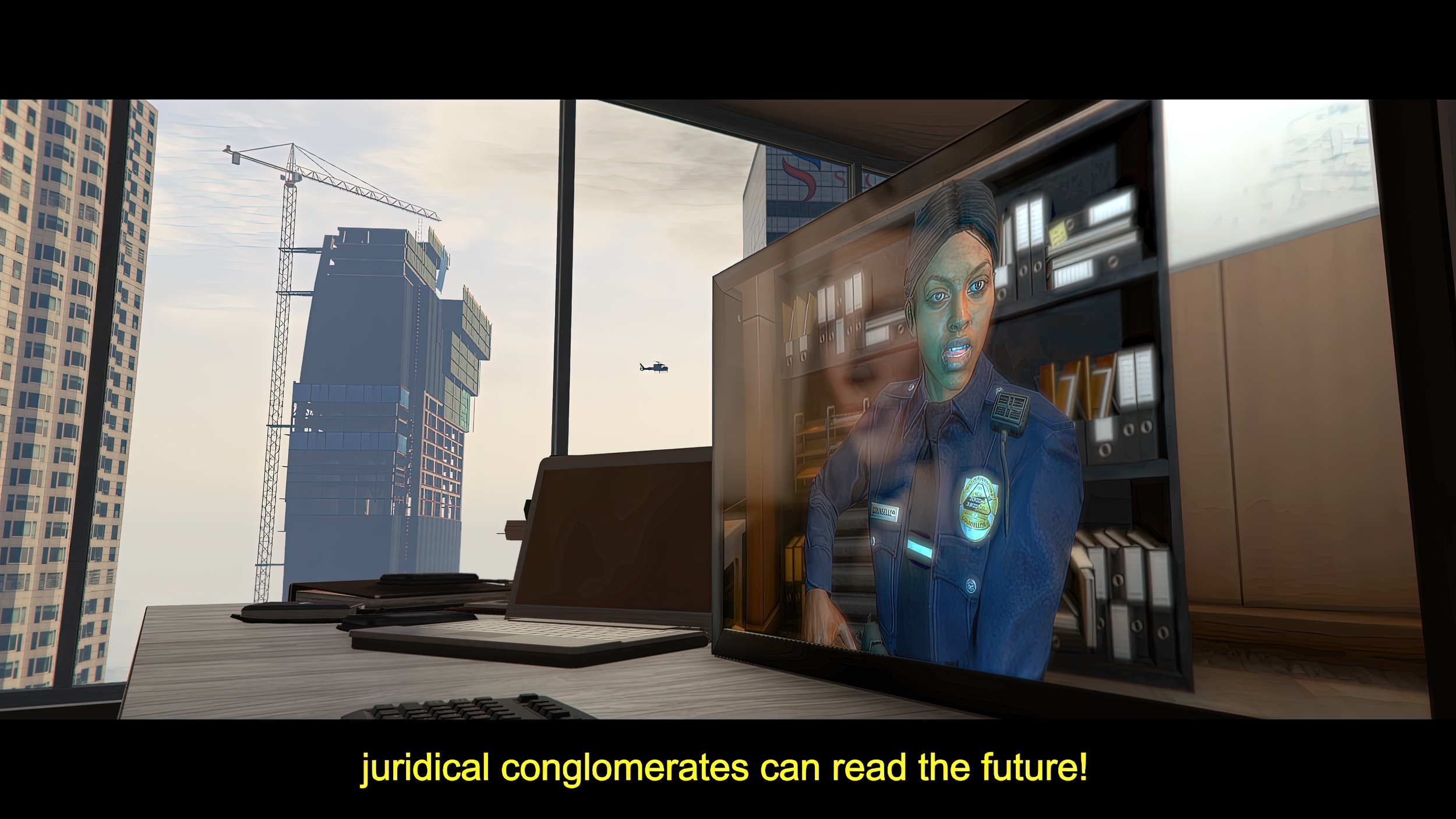

single-channel HD video (1920 x 1080, MPEG-4 AAC, H.264) comprising machinima, 3D animation, and found footage with sound, 90’ 1”, 2022, Canada

Created by Steven Cottingham

WORLD PREMIERE

Bruce Sterling famously stated that the future is “old men, in cities, afraid of the sky”. In Steven Cottingham’s cyberpunk masterpiece filmed with/in an unrecognizable Grand Theft Auto V, Chain-link, the future is even scarier: pervasive surveillance, carceral capitalism, and techno-feudalism.

Steven Cottingham is an artist based in Vancouver. His work concerns the politics of visualization. Recent exhibitions include Natalia Hug Galerie (Cologne, 2022), Artists Space (New York, 2022), The Polygon Gallery (North Vancouver, 2021), and Catriona Jeffries (Vancouver, 2021). From 2018 to 2021, Cottingham co-edited the art theory periodical QOQQOON, and in 2021–2022 he participated in the Whitney Independent Study Program. Chain–link (2022) is his first feature film.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe your encounter with machinima as a video art genre?

Steven Cottingham: Machinima, for me, constitutes a diverse array of creative practices. In some ways, it is like working with found footage, accepting certain parameters at the level of content while totally reworking its form through editing and sound work. It also bears a strong relationship to choreography or puppetry: whereas conventional animation allows the filmmaker to keyframe every pose and dial in every simulation, machinima requires making room for (mis)interpretation. But of course its definitive element is found in repurposing an existing virtual world, playing a video game against the grain without regard for scores, quests, or narrative. I like Jeffrey Bardzell’s writing on “machinimatic realism, describing how reality can be depicted either with recourse to cinematic naturalism, engaging with the game world as if through a movie camera, or by portraying the totality of the game interface and its artificial point of view (this is the realism of streamer footage). Artists like Harun Farockior Sondra Perryryhave made use of video game footage in an observational capacity: their intervention is not overly palpable in the shots themselves but in the way they recontextualize the footage to make broader points about culture and labour. And then there are artists like Hito Steyerl or Martine Syms who privilege the glitchy qualities of game aesthetics to produce imagery that feels like machinima, even if it was derived through other means. As games occupy an increasingly central position in the culture industry, their unique modes of perception become commonplace depictions of the real.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you discuss the origins of Chain–link and its main themes? You describe this work as a “cyberpunk jailbreak machinima”. Is the recent revival of cyberpunk as a literary and cinematic genre the proof that the fictions and fantasies of the 1980s have become 2020s reality?

Steven Cottingham: Despite beginning as an exploration of surveillance systems and the use of AI in prisons, Chain–link, for me, is primarily concerned with the dialectic of creativity and constraint. This tension drives the narrative as characters grapple with their own limitations and desires, and it also describes the very craft of machinima, where restrictions in the mode of production constantly necessitate creative workarounds.

Initially I wanted to flesh out some anxieties around surveillance capitalism and data leaks by putting characters into circumstances where these anxieties would be actualized, seeing how they might navigate a corrupt judicial system and a penitentiary devoid of any privacy. I was also drawing from heretical medieval sects like the Cathars and Waldensians and descriptions of how they navigated a world purportedly under omniscient surveillance by an ambivalent God. I had lots of ideas for speculative world-building, but in order to produce a coherent narrative experience, I also felt the need to incorporate familiar genre conventions to give the story some structure. Although the virtual reality depicted by cyberpunk is in practice an inconvenient way to navigate virtual space, it still serves as an adequate visual metaphor for incomprehensibly vast servers and data fields—not to mention the constant juggling of virtual/actual worlds through an array of screens and surfaces. And, of course, the notion of a renegade hacker or data smuggler has some overlap with the open source modding communities whose software proved indispensable to the production of this film.

Matteo Bittanti: Among other things, Chain-link is a stunning technical achievement. You made your entire machinima with/in Grand Theft Auto V using dozens of mods and add-ons. How long did it take? Can you describe your process? What role did Liljana Mead Martin play? What were the hardest challenges that you faced?

Steven Cottingham: The entire project took eight or nine months. I was doing a residency with the Whitney Independent Study Program in New York and had some grant funding to cover my subsistence for the year, so I was really able to take on a large scale project. Liljana is my partner, and she was an invaluable part of making this film. She contributed a lot to the characters’ arcs and the narrative’s emotional tenor, helping all of the disparate elements find cohesion. Throughout the project, she would offer feedback on script drafts and rough cuts. I couldn’t move forward on a sequence without showing it to her first!

I also relied very heavily on YouTube tutorials – whanowa’s work on GTA V machinima techniques is absolutely crucial. Because of him and many other modders, I was able to use GTA V basically as a piece of software. Finally, I probably read Hugh Hancock and Johnnie Ingram’s Machinima for Dummies about a dozen times. It’s such an inspiring introduction to DIY filmmaking, and a deeply engaging picture of a certain period in machinima’s history.

Unlike in conventional filmmaking workflows, I worked on the film in a chronological fashion, and would edit scenes together almost as soon as they were shot. Having never done something like this before, this workflow allowed me to maintain a sense of what the finished product could be, and also let me see very quickly whether or not certain approaches would work. The script was constantly reworked as I discovered limitations in the game engine or animation library. Sometimes I could circumvent these with the use of VFX – I would often pull models out of the game and reshade or reanimate them in Blender, and then composite the results together. Definitely the hardest part was trying to elicit empathetic performances from the characters. I really had to find emotion in the cinematography, editing, and music, as GTA lacked any animations to convey intimacy, and it was extraordinarily difficult to even get the characters to make eye contact with each other. Also, without any budget for actors, I used AI text-to-speech voices – convincing myself that this could at least work as a sort of Brechtian theatre. In the end, I think the voices are serviceable in the context of a highly-surveilled prison, where everyone is deeply guarded about what they reveal of their inner lives.

Matteo Bittanti: Chain-link incorporates several found footage videos. Your mixing of different kinds of video sources seems to indicate that, in the digital age, images are just bits and there’s no qualitative difference between the various types…

Steven Cottingham: The thing about machinima is, you are always looking at two works of art at once. There is the work of the artist or filmmaker and the narrative they have constructed, and then there is the game world which huge studios have built – all of it deeply art-directed to service their own (now displaced) narrative. So, in this way, I felt that the machinima elements were already multi-textural, and adding news footage, satellite scans, or action from other video games enhanced the film world’s sense of realism rather than detracted from its coherence. There is of course a qualitative difference in these textures – some derived from cameras and others constructed with computers – but in the context of the film I felt I was able to use found footage whenever the film’s perspective became so macro it left the realm of fiction or speculation to become more grounded in our own (highly mediated) experience of reality.

Matteo Bittanti: At one point during Chain-link, a character states, somehow apodictically, that “Data speaks louder than words”. As an artist, what is your take on data-driven art? What becomes of human ingenuity in the age of AI-generated artworks? What kind of agency do artists have today?

My research into data harvesting and AI-generated content has taught me the importance of historicizing these technologies. Scientific management, statistical predictions, and “labor-less” images all date back a hundred years and more. Ultimately “any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic”, and historical cultures actually have a lot to say about magic. Magic’s importance comes from how it augments social relations, if it is used in good or bad faith, and its appropriation in power hierarchies. So, in this sense, I don’t feel the need for a new ontology to make sense of what we now call AI. I respond instead from an economic perspective. There remains, I think, a societal need for artistic creativity that extends beyond mere images and encompasses a playful criticality of concepts, signs, and events. That this societal need is rarely remunerated is unfortunate but not the fault of competition from AI-generated content. Artists are obliged to creativity as much as they may be drawn to it: artistic agency begins with that which is already at hand. Supply chain interruptions and technocratic prerogatives have changed what kinds of resources are readily available for creative interpretation. The difficulty is in overcoming inherited (and systemic) preconceptions about what art should look like.

InPhostphotorealism (2022), you investigate the political dimension of images and the ideologically charged gaze of the bodycam. You argue however, that deception, manipulation, and fakery have always accompanied the history of the image. So, is there anything new in the development of the technologically constructed domain of “the visual”? If power, rather than realism, is what really matters today, is technology altering in any way the status quo or simply ratifying existing hierarchies? Does sousveillance as a bottom up tactic represent an alternative to surveillance?

Steven Cottingham: Of course the technological form of mediation changes – at a seemingly ever-more rapid pace – and likewise societal expectations of imagery changes with it. In many ways, the verisimilitude or believability of an image is indebted to the acuity of its rendering. But it is a somewhat separate question of what kinds of representation resonate within dominant culture. Right now, many industries – film, art, and video games included – are increasingly attentive to diversity and making efforts to include racialized or other historically marginalized perspectives. This is a new development within the Western worldview, but it is arguable how much this has to do with technology – perhaps the ability to capture abuses of power on smartphones has changed how our society pictures itself – but the problem remains that no image is self-evident. The circulation and repetition of images is what lends them their realism, and context plays the biggest role in the suspension of disbelief. Cultural shifts owe a lot to technologies of context, like social media, news, and publishing platforms, and we are seeing those leveraged for both coercive and emancipatory means.

Matteo Bittanti: You also argue that “We live in an era where photography no longer enjoys a privileged relationship to realism – a status made even more tenuous by the proliferation of photoreal computer-generated images, deepfakes, and cameras that record inhuman perspective”. So what does it feel and mean to make art in the age of simulacra?

Steven Cottingham: In some sense, the end of the photographic paradigm has allowed imagery to return to the interpretive and illustrative role it always possessed. In fact, I would go so far as to say that imagery derived from virtual reality possesses a higher degree of verisimilitude than photography ever had! In part this is because the image can no longer purport to be an objective documentation of an actual event, but more than that, it is because all imagery carries an intrinsically virtual function. Especially in our current paradigm of surveillance and simulation, image-based data is gathered not necessarily for the purposes of observation, but to generate patterns and make predictions. And sometimes, these predictions become self-fulfilling, which opens up a very different kind of relationship to the real than the indexicality of photography. Hyperreality or not, I tend to follow the Russian Formalist school of thought which argues that the realist capacity of any representation is measured not by its relationship to empirical sensation, but by its resonance with cultural beliefs and reigning ideological worldviews.

Steven Cottingham, Surveil/simulate immerse/repulse, 2022, Inkjet print, 24 x 18 in. (Courtesy of the Artist)

Matteo Bittanti: Can you discuss your diagrammatic artwork Surveil/simulate immerse/repulse? I find your categories and their interaction very interesting, especially when it comes to the incorporation of SimCity as the quintessence of simulation.

Steven Cottingham: This is from a series of work that attempts to provide loose taxonomies for the multi-textural imagery of our current media landscape. My goal was mostly to move beyond binaries of real/fake or human/nature, instead finding less ideologically-charged categories to use for evaluating image grammars. For instance, one work focuses on imaging technologies, making a distinction between “captured” and “constructed” images, while also incorporating a spectrum with human vision on one end and machinic modes of perception (thermal, x-ray, wireframe, etc.) on the other. Another more culturally-oriented work proposes a differentiation between “hallucination” and “verification” on one axis, acknowledging that even esoteric experiences have a place in the fabric of reality, and “alienation” and “acculturation” on the other, illustrating that some realities may be at odds with the dominant cultural narrative. In the work Surveil/simulate immerse/repulse, I collage different pictures of crowds so that each image occupies a quadrant delineated by the eponymous binaries. The upper left zone, where both surveillance and immersion are at their extreme, is occupied by a protest. I was thinking about immersion as a mode of representation, a kind of hyperreal metonymy, and also thinking about what overlap exists between political representation (in the sense of democratic institutions representing the people) and aesthetic representation. SimCity occupies the lower right zone, where simulation and repulsion are at their extreme. Repulsion, for me, functions as a sort of analogue to mediation, albeit with different connotations. It is a form of retreat, whether into the bubbled individuality depicted in the traffic jam, or to the virtual fantasy of the video game. And yet, there is the qualitative content of the image, which depicts a redlined neighborhood, resonating with the race and class-based tensions represented in the protest. So the retreat is curtailed because, in a sense, every mediation is itself mediated by the greater context of power, social hierarchies, and inherited abstractions.

Chain-link

digital video/machinima (1920 x 1080, MPEG-4 AAC, H.264), color, sound, 90’, 2022, Canada

Created by Steven Cottingham, 2022

Courtesy of Steven Cottingham, 2022

Made with Grand Theft Auto V (Rockstar Games, 2013)