Ice Cream President

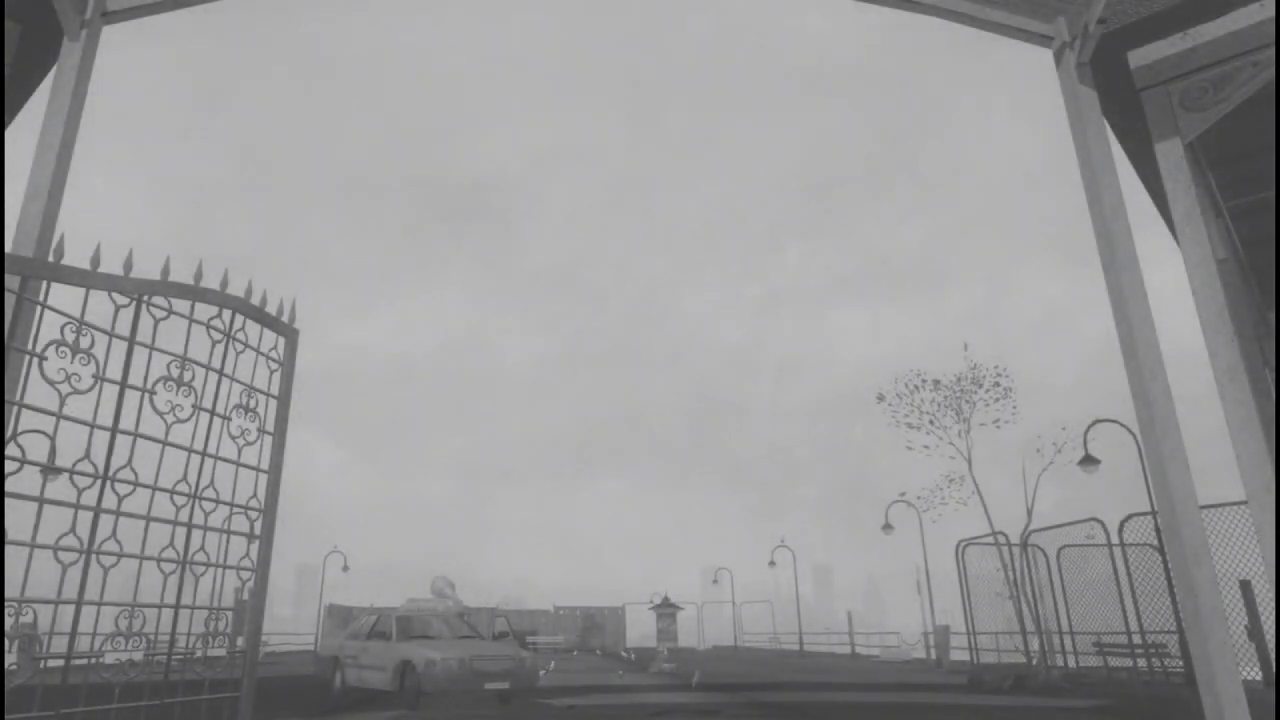

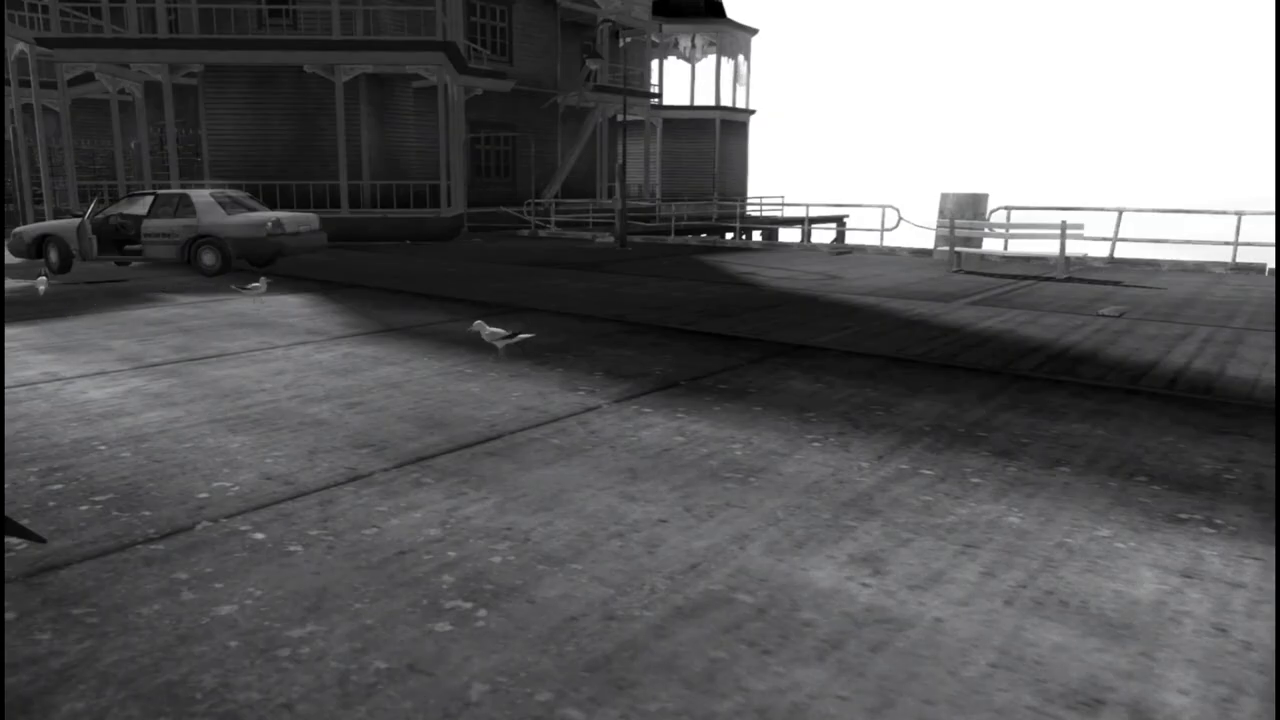

digital video, black and white, sound, 06’ 37”, 2020, United States

Created by Kent Sheely

Fifteen years after its release, the Hitman: Blood Money’s disarming yet lethal ice cream truck returns in this bleak machinima that focuses on another kind of tragedy. What happens when the video game imaginary breaks the fourth wall and enters the so-called “reality”? You may get two scoops of Ice Cream President.

Kent Sheely (b. 1984, United States) is a new media artist based in Los Angeles. His work draws both inspiration and foundation from the aesthetics and culture of video games, examining the relationships between real and imagined worlds. Much of his work centers around the translation and transmediation of symbols, concepts, and expectations from game space to the real world and vice versa, forming new bridges between simulation and lived reality.

Matteo Bittanti: How are you these days? How did the pandemic affect your personal life in the last twelve months? And how did you manage to make art under lock down?

Kent Sheely: I’m doing okay! During the pandemic, like many others, I was working from home and not seeing very much of the outside world. I struggled quite a bit with finding the creative energy to make art over the last year but managed to channel what I had into making some pieces that reflected the way I was feeling about the state of the world. I found that the tone of my work during that time shifted noticeably to a darker one from my generally more tongue-in-cheek, darkly humorous outlook, which I think was completely appropriate, all things considered.

Matteo Bittanti: Speaking of sinister symbols, Ice Cream President features — somehow unsurprisingly — an ice cream truck, which I automatically associate with one of the most brutal scenes in John Carpenter’s Assault on Precinct 13 (1976). More recently, on The American Conservative, Addison Del Mastro called the ice cream truck a true symbol of Americana, arguing that “you shouldn’t worry about the death of Western civilization so long as the average suburban American neighborhood still has ice cream trucks.” I’m not sure if I agree with that diagnosis. Speaking of “civilization”, in 2014 NPR reported on the racist meaning of the original ice truck song, which is not surprising per se given the context that Del Mastro alludes to, but dispiriting nonetheless. In your machinima, the ice truck is more than dead… It’s a fossil… Can you describe the genesis of Ice Cream President? When did you first come up with the idea? And what do you make of these ambiguous connotations?

Kent Sheely: The idea for Ice Cream President was born during my revisitation of Hitman: Blood Money (2006), and I was immediately drawn to the abandoned pier and defunct ice cream truck in the game’s first mission. The focus on the truck itself in the piece was absolutely intended as a grim reference to American culture, but even more so in this case it represents former President Trump and his reported obsession with ice cream, which is why his speech is being blasted out of the truck’s loudspeakers. I was working on it during the zenith of the pandemic and the sunset months of an unchecked fascist regime, and I think my anxiety about the state of the world and outlook on the future of our country informed the bleakness of the piece. The setting is meant to feel post-apocalyptic, as if the inertia of those in power had resulted in the complete breakdown of society and the end of human contact, the only remaining evidence of the former world being this recording of our President delivering a hollow, self-aggrandizing speech that is gradually drowned out by a lilting, dirge-like version of patriotic orchestral music. It’s intentionally devoid of optimism.

Matteo Bittanti: Perhaps the problem is bigger than you think. In fact, mainstream media are currently debating if President Biden is perhaps an even bigger fan of ice cream. What do you make of this gelato conspiracy?

Kent Sheely: First, it’s really funny to me that ice cream has been such a prominent theme in politics in the last years! When discussing politics (especially with strangers), it’s common to hear things like “Oh, so you didn't like Trump? Well, here’s something the OTHER guy did that’s also terrible! What do you think of that?” That’s the problem with the two-party system in which we’re perpetually locked; every election for a lot of people involves choosing between the lesser of two evils, so some just refuse to vote entirely because they will never feel truly represented. That’s the issue: We’re not, and, unfortunately, that’s by design.

Matteo Bittanti: It’s remarkable how the United States went from outstanding incompetence in handling the pandemic – Alex Gibney’s documentary Totally Under Control provides an effective, albeit depressing summary about everything that went wrong during the (first) Ice Cream President regime – to one of the leading countries in the world for vaccination rates - although that too reached a plateau. But the irrational, nihilistic forces that brought the country to the brink of civil war have not disappeared. On the contrary, they may retake the White House in the next election cycle, not to mention the House and the Senate. The United States seems to be stuck in a vicious cycle: every step forward is followed by two steps back. What does it feel to live in a society whose political class is even more deranged than the fictional lawmakers depicted in Grand Theft Auto V? I mean, when a President proudly says things like “I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn’t lose voters,” how can you tell the difference with Liberty City’s fictional gangsters? Tim Murphy argues that the entire GOP hasbecome a party of trolls, shitposters, and cosplayers. Do you ever feel that the Imaginary, in Lacanian terms, is now exhausted, i.e., unable to keep up with lived reality?

Kent Sheely: I think the simple answer is that fiction is created with structure and purpose. The characters have believable motivations informing their decisions, which ultimately leads to some kind of satisfactory resolution. There are heroes and villains to serve as focal points, around which the narrative can be crafted. The real world, on the other hand, has far more moving parts to have been planned and orchestrated. Even the most outlandish parodies of true situations are designed to make sense and serve a narrative, to speak truth and provide context to the chaos we see in our real world. There are no heroes or villains for us, because real human beings are too complicated to be described in bullet points outlining their motivations and the backstories. Fiction is idealized by design, or it would be just as much of an unpredictable mess as our own reality.

Matteo Bittanti: In the recently published book Norms Under Siege. The Parallel Political Lives of Donald Trump and Silvio Berlusconi (2021), Edoardo Fracanzani convincingly argues that political support has morphed into a new form of fanaticism and hooliganism. A significant size of the electorate worships the “Strong Man” as if he were a messiah. Meanwhile, politics, which was already highly performative, has degenerated into a carnivalesque spectacle which feeds on heightened polarization that often produces real violence. This new “Strong Man” exploits white resentment and recycles vernacular imagery – memes, empty slogans, and iconic images – to cement his base. Why do you think that gaming subcultures are especially attracted to the figure of the autocrat, the irreverent, and transgressive Joker? This phenomenon is, by no means, limited to the United States, but on top of my head, I can’t think of another country where a “hive mind” responsible for a highly orchestrated hate campaign like Gamergate was able to install a meme-President into the White House. If you look at the Italian counterpart, Silvio Berlusconi, social media and gaming played a marginal role…

Kent Sheely: For a long time, the “gamer” subculture was associated with feelings of being shunned by society at large. That has changed in recent years as video games have become more ubiquitous, which I think caused a lot of the people who had been wearing that label as a badge of honor to be insulted by the shift and look for new ways to express their rejection of what they consider to be mainstream. This gradual change coincided with the cultural zeitgeist leaning toward more progressive ways of thinking and treating individuals, or “political correctness,” which many people entrenched within the group considered to be a violation of their freedom of speech. It’s no coincidence that so many gamers are also members of other counterculture groups like 4chan, who have long believed that free speech is the only hill worth dying on.

Cut to a few years ago when Donald Trump first started running for the Presidency. Here was a political candidate who wasn’t afraid to say things that made people angry, who openly mocked the society that they felt had rejected them and had the power to roll back the wave of change that was making them feel like they were being further ostracized and forced into a corner. I’ve spent enough time playing video games online to see the similarity between the people who voted for Trump and those who have spent years fighting for their right to do absolutely anything they want on the Internet, even if it brings harm to other people.

Matteo Bittanti: It’s interesting that you call 4chan “counterculture” rather than “subculture” (What would Angela Nagle say?). Video game narratives and mechanics often introduce possible futures. In a sense, they bring into the realm of possibility - they presentify — what may happen next, as Richard Grusin’s evergreen theory of premediation (hereby hyper-simplified, admittedly) suggests. In another recent book titled The End of the End of History (2019), the authors argue that the implosion of the neoliberal dogma led to the rise of anti-politics, a mix of populism, online histrionics, conspiracy theories, and good old propaganda. If you were to predict what comes next – that is, what comes after the End of History – based on your great expertise with video games — an oracular medium — what should we expect?

Kent Sheely: Thanks to the unchecked evolution of the internet, the world has shrunk to the size of a smartphone, and the media we consume is also being compressed into an increasingly smaller space. Everything that happens is captured on video, shared, written about, and is open for heated debate. Comment sections are filled with political discourse, no matter how unrelated, and politicians reference pop culture as a way to sway voters to their side. Brand integration in all entertainment spaces has become numbingly commonplace and will likely only get more egregious as time goes on. The weird corporate-sponsored reality of science fiction is quickly becoming our reality, and we seem to be okay with that.

What happens next? As our planet runs out of resources and heats to the point that it can no longer support life, the people who created this weird future for us will strike out for Mars and leave the rest of us numbing ourselves with our digital opiates, ordering pizza without taking our eyes off the latest Netflix series. But at least artists will have plenty of material for the years to come!

I’m being grim and a bit hyperbolic here, but honestly it does feel as though the choke hold capitalism has on our daily lives is only going to tighten as we go forward, unless of course we can collectively find a way to retake control of the wheel from the greedy hands of corporations and government.

Matteo Bittanti: In the seminal Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business (1985), Neil Postman argued that in a society in which entertainment has become both the catalyst and necessary outcome of every activity — from politics to education, from journalism to art — the dystopian turn is a matter of when rather than if. In one the most fascinating chapters, “The Huxleyan’s Warning”, Postman argues that we already live in a dystopia, but not in Orwell’s 1984. We live in Huxley’s Brave New World, a world in which people medicate themselves into bliss and adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think, thereby voluntarily sacrificing their rights: distracted by their electronic gadgets and endless stimulation, people simply become bored of democracy. In the 1980s, Postman saw television as “the drug of the nation”. Today, social media and video games play a much bigger role in our lives than TV, even though the “stupid box” remains the most popular medium in the US as of today. As an artist you are a “man of integral awareness”, to quote McLuhan, somebody who sees the contingent moment with uncommon clarity. What role does technologically-driven entertainment play within our culture? Is Postman’s warning still valid today?

Kent Sheely: A decade ago, I wouldn’t have agreed with such an outlook and would have described it as “technophobic,” because the technologies we enjoy still do have their very valid positive uses. For example, during the pandemic, lots of people (including myself) were able to maintain connections with friends and family and even spend time together in digital spaces. However, this power comes with a price, and the companies who control these systems are deliberately using them to manipulate us despite our awareness that it’s happening. Social media was a gigantic tipping point in this direction; once we gained the ability to see the whole world all at once, it became an all-consuming addiction, and every idea became intentionally polarized. The internet, media, entertainment, and all of their offerings are now a homogeneous slurry that we can’t stop drinking. Don’t get me wrong; I still don’t think entertainment technology is entirely corrupt and dangerous, but we all need to maintain a sense of perspective and keep ourselves in check.

Matteo Bittanti: Artists play games differently than most players. They often play against games, as Peter Krapp suggested. And yet, there is some overlap between artistic forms of counterplay and vernacular practices. Consider, for instance, pacifist runs in extremely violent games, like first-person shooters. You attempted two pacific runs in Call of Duty in 2016 and 2019. Reflecting on your original run, in 2016, you wrote: “What began as a superficial challenge in (a) game otherwise intended for escapism turned into a deeply philosophical experience for me, and I think the outcome is worth scrutinizing. I refuse to accept that there is any form of interactive media that is not worth exploring and pushing to its limits, even if that means taking the exact opposite approach and just stepping back to let things play out as they will.” Did “replaying” this experiment three years later led you to new insights and surprises, or did it just corroborate what you had already discovered?

Kent Sheely: The 2019 reboot of Modern Warfare that I played last year feels like a much different game than the one from 2007 in both its tone and intentions, and playing through the newer one as a staunch pacifist did not give me the same satisfaction by any stretch. Between the two playthroughs I learned a lot more about the process through which big-budget games like that are produced, and understanding that the US military has been advising the developers for years left a sour feeling in my stomach that I couldn’t overcome. This is certainly noticeable in the direction the story takes, but the publisher has also publicly stated that their game is not political, an assertion that is absurd and laughable even without knowing any of the details of the game’s plot. There are choices made in the writing that make me furious, like the historically revisionist take on the infamous “Highway of Death,” the site of a war crime committed by Coalition forces against Iraqi military and civilian refugees who were attempting to retreat from Kuwait. In the game, this atrocity was committed by the Russian military, the adversary these games frequently prop up as an “acceptable” target for the player. In a series of flashbacks, the player’s character is a young girl from a fictional Middle Eastern country who is forced to watch her parents executed, again by the Russian military, shifting focus away from the United States’ own atrocities committed in that part of the world. Modern Warfare is certainly not the only game recognizable as blatant propaganda (America’s Army is literally a recruitment tool) but the way they’ve tried to dodge responsibility and declare it to be “just a game” is sickening. It took me a long time to figure out how to finish that series, and in the end I ultimately decided to make my disgust the focus of the piece and end the final video by refusing to even proceed, closing on a static shot of a white flag and symbolically giving up on the whole endeavor.

Matteo Bittanti: In many ways, Ice Cream President is in dialogue with a previous machinima of yours, Aspect(2014), whose main theme is the notion of projection. In the latter, we see the shadow of a soldier from Arma II projected on the ground as M.L. von Franz describes the function and meaning of projection in Carl Gustav Jung’s theory of psychology. In A Man and His Symbols (1964), von Franz states that “projections of all kinds obscure our view of our fellow men, spoiling its objectivity and thus spoiling all possibility of genuine human relationships” (p. 172). Jung — von Franz argues — connects the shadow, which we unconsciously project to others, to political agitation, because it represents “the opposite side of the ego” and embodies “those qualities that one dislikes most in other people.” Video game avatars are, in many ways, shadows: an expression of our repressed desires, aspirations, anxieties or dreams. The soldier-shadow is a recurrent figure in your work. What does he represent to you?

Kent Sheely: I’ve often made the connection between video game avatars and the Jungian idea of the “shadow self,” as the player is encouraged to act on impulses that they never would, or could, in the real world. In the most basic manifestation of the idea, the shadow makes its appearance any time we find joy in committing acts of fictional violence on simulated characters, or even on the avatars of friends and strangers alike in brutal competitive games. That’s the version I had in mind when putting myself into the boots of the shadow soldier from Arma II as seen in Aspect. It’s not just about indulging those power fantasies, however. The shadow self in video games also provides a safe space to engage with concepts that cause us anxiety without being physically exposed to those realities. I see that transference in almost every game-based work I create, simply because the act of capturing those moments requires me to act within those fictional situations. In the case of Ice Cream President, I think the shadow represents my quiet, selfish acceptance of the world’s end. Perhaps that version of myself even welcomes that bleak but eerily calm future in a way, as it would certainly mean the hastened arrival of a dreaded inevitable outcome, like ripping off a bandage.

Matteo Bittanti: In the United States, you will be fined by the police if you walk outdoors with an open can of beer. At the same time, in most states, it is perfectly fine to walk around with a machine gun, thanks to the ever expanding “open carry” laws. One of the side effects of the pandemic is that more guns are being bought by more Americans than ever before. In fact, according to Pew Research, today the number of guns vastly surpasses the population. Your fascinating 2013 project Open Carry — not to mention the equally poignant Ready for Action series — seems now eerily, if not tragically, prophetic. How do you explain the fascination for weapons of mass destruction in a nation that is always eager to export “democracy” and “freedom” to other countries, from the Middle East to South America? And how do video games contribute to propagating these “values”?

Kent Sheely: Our country’s fixation on guns is not a new development at all; we were always heading toward this situation. Thanks to an unfortunate lack of foresight by the people who wrote our country’s constitution — though to be fair, I don’t know how they would have predicted the invention of the assault rifle —, there are a lot of people here who see owning guns as an integral part of their rights as an American, forever. The rampant propagation of guns and proud obsession with ever-increasing firepower seems to be a microcosm of our amassing of nuclear weapons as a deterrent, both an extension of our government’s long-held complex about being both self-sufficient and superior. It feels like a domestic arms race that only gets more intense when politicians start talking about setting restrictions on what kinds of weapons ordinary citizens are allowed to have.

Matteo Bittanti: Lastly, I wanted to ask your take about in-game photography. You were among the very first artists to critically investigate photographic practices within video games with a series of innovative projects such as DoD (2013), World War Redux (2009), and First Person (2013). Originally, in-game photography was a relatively niche activity, one that often required modding or hacking, but nowadays it is literally integrated in the hardware, both in consoles (think the SHARE button of the PlayStation controller) and PCs (think Nvidia Ansel/GeForce Experience in most GPUs). As someone who has not simply engaged with this practice but clearly demonstrated its artistic potential, do you think that game photography can still evolve in interesting, unexpected ways now that it has been (almost) completely co-opted by the industry?

Kent Sheely: The appropriation of art, and the technology used to create it, for commercial purposes has always been part of the equation, especially given the pace at which the latter advances now. Screenshots have become something akin to vacation snapshots for those who take them, and game developers include the feature primarily for use on social media – it’s free and self-generating advertising! The practice of making art with screenshots is still viable, it just takes more effort now to say something interesting with it since the basic idea of taking a screenshot is no longer novel.

Art should always be evolving; artists should always be tasking themselves with figuring out how to push it to new places.

Ice Cream President

digital video (1280 x 720), black and white, sound, 06’ 37”, 2020, United States

Created by Kent Sheely, 2020

Courtesy of Kent Sheely, 2021

Created with Hitman: Blood Money (IO Interactive/Eidos Interactive, 2006)