HALO

digital video, color, 5’ 55”, 2016, United States

Created by Cassie McQuater

Originally commissioned by Electric Objects

Special thanks to Luca Miranda

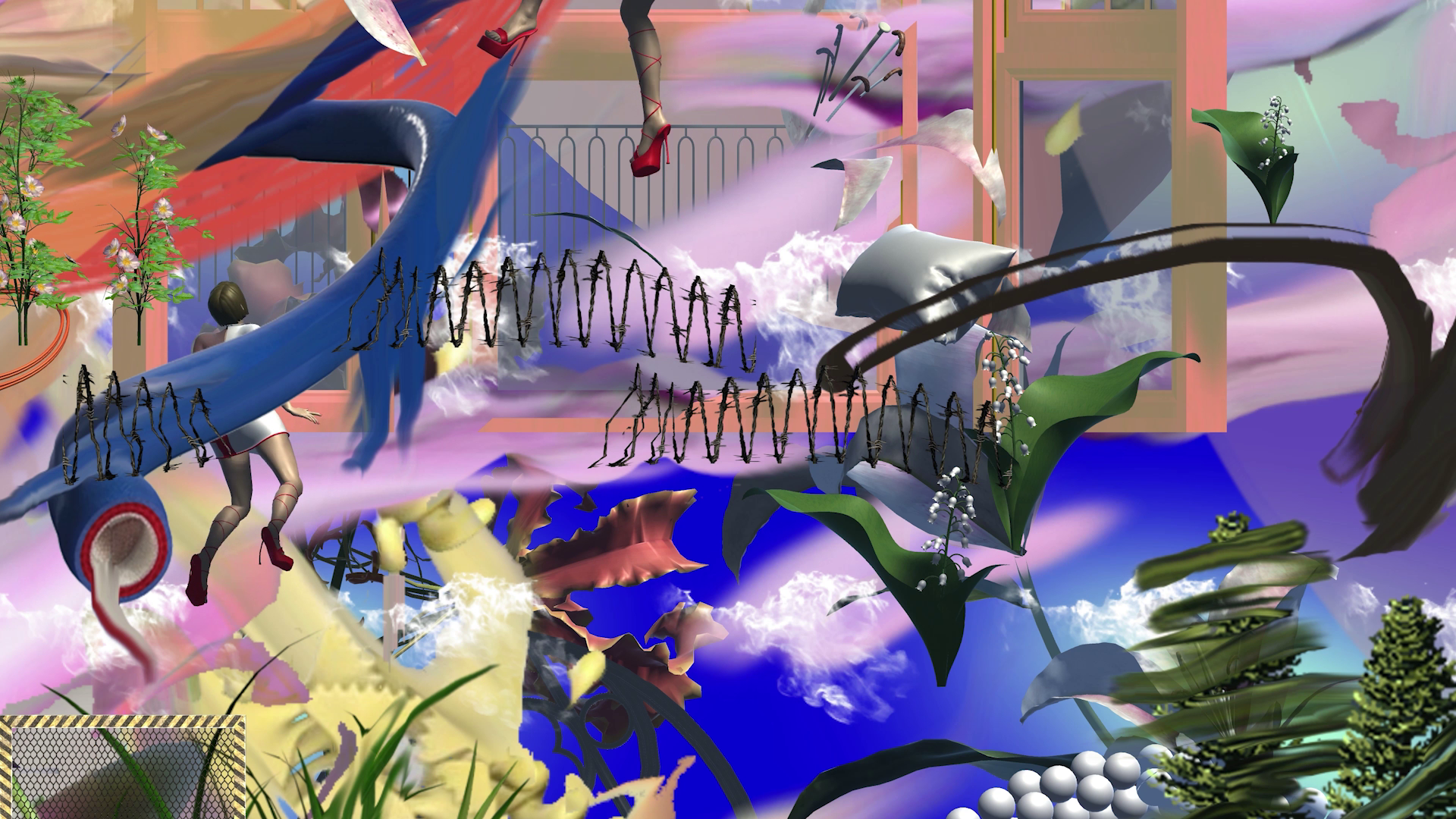

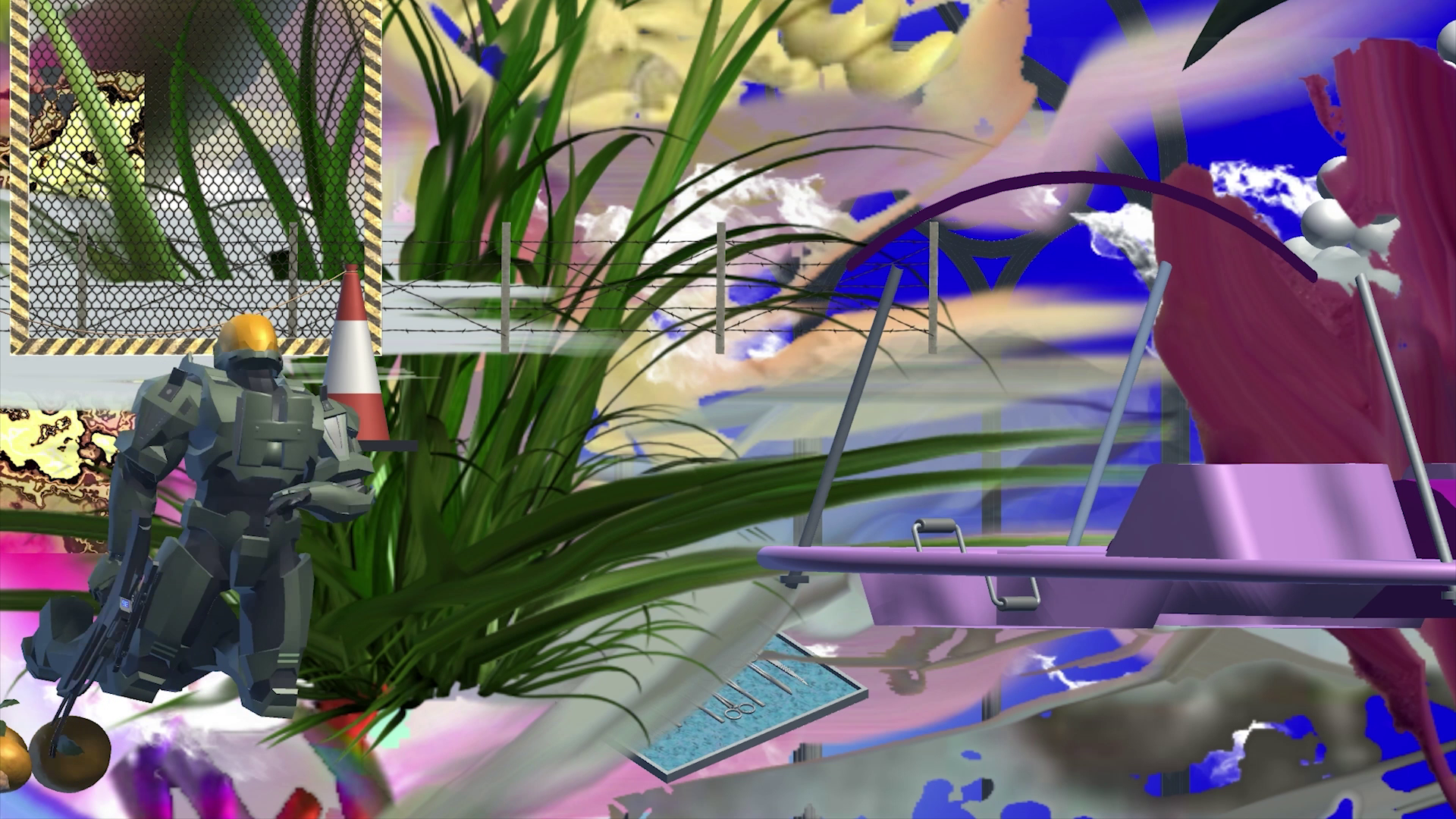

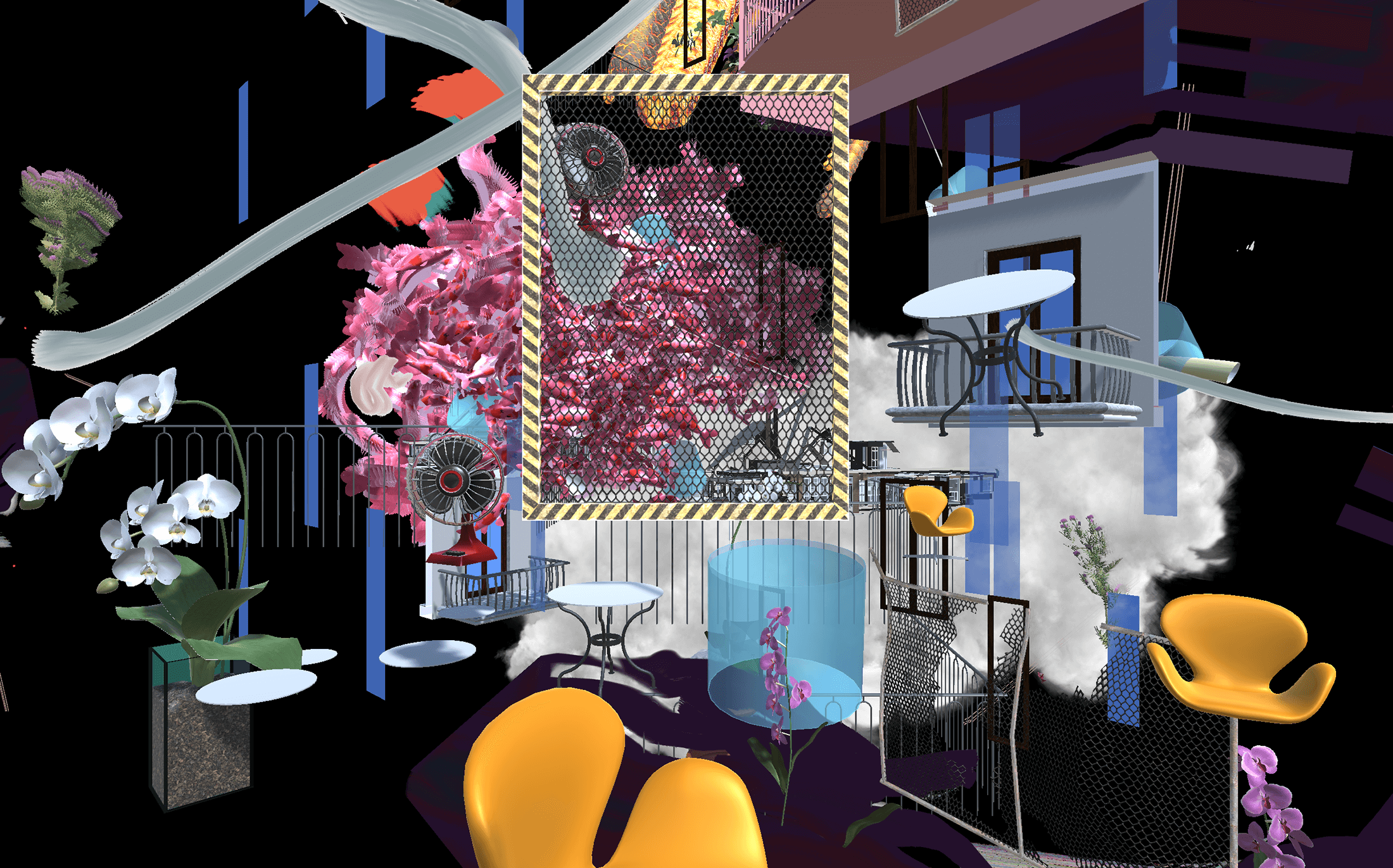

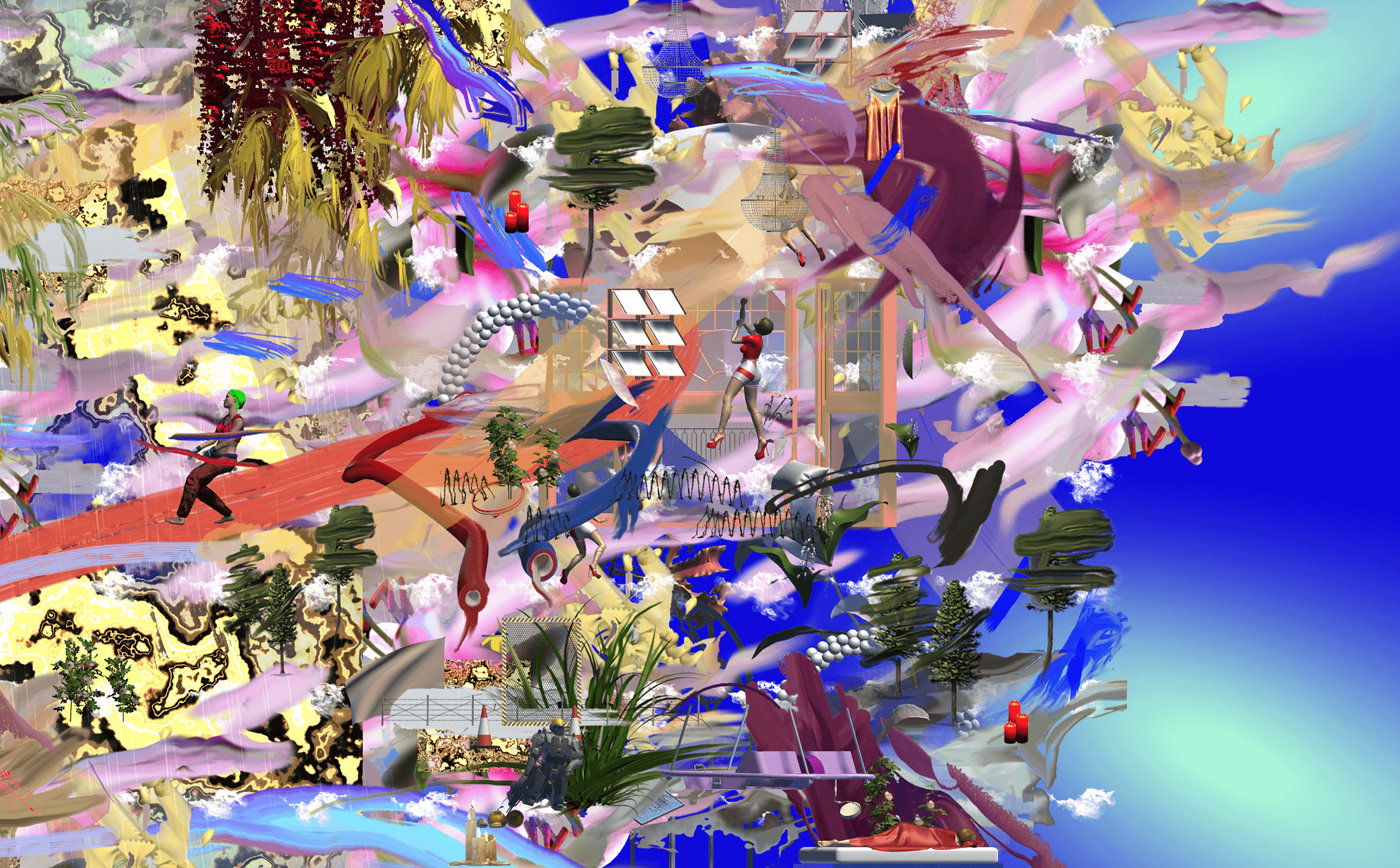

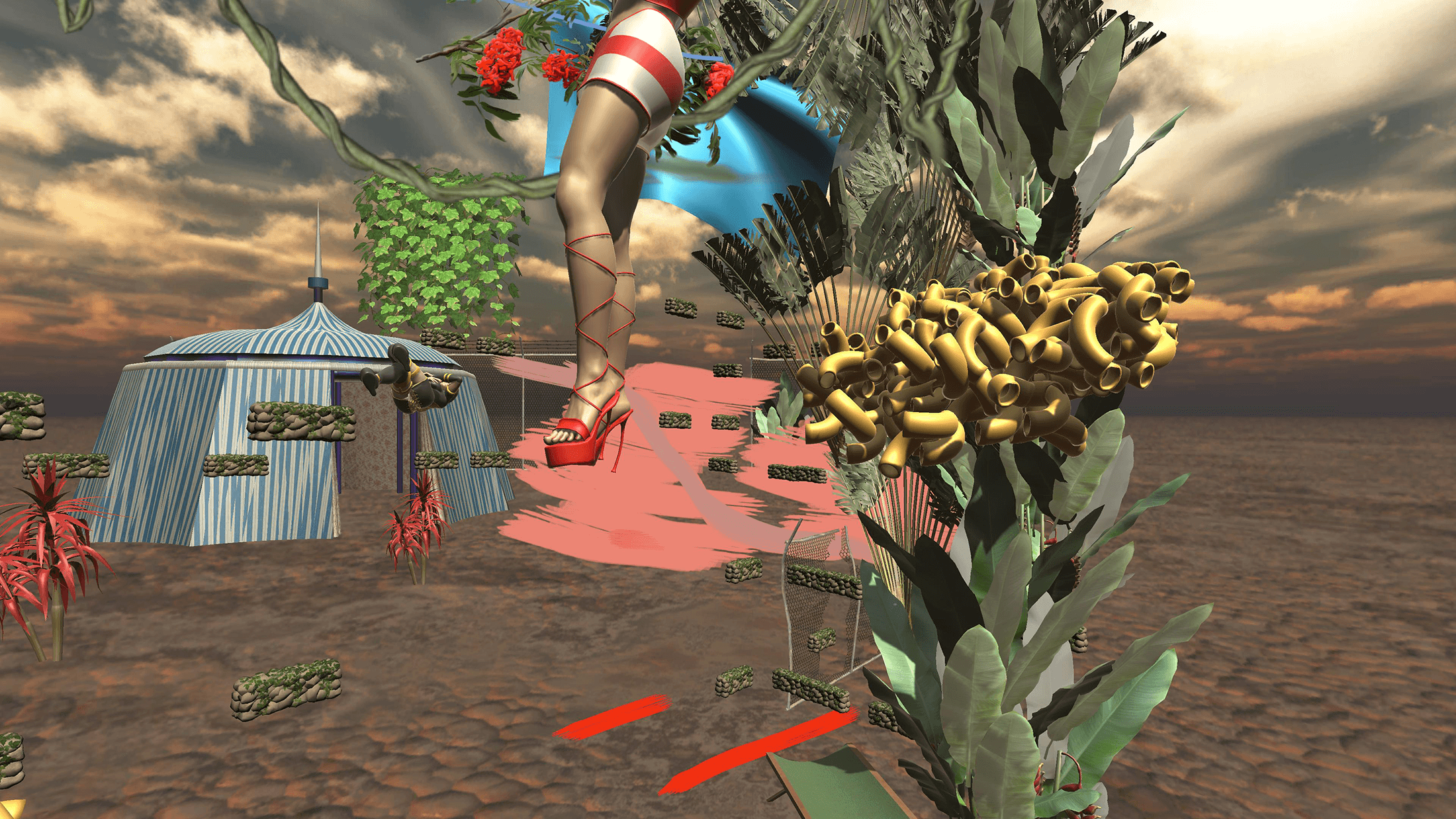

In these six animated paintings presented as a single channel video, the artist reenacts situations and motifs from the first-person shooter series Halo and the erotic videogame Dream Stripper. Conceived as a dynamic, virtual collage, HALO shows short stock animation loops of characters dying over and over, with koi, dining chairs, asteroids, guns, flowers, torches, pinball machines, candles, and discarded pillows floating around them, creating a hypnotic motion.

Cassie McQuater is an American artist working with digital media, developing and designing video games and other interactive pieces and installations. Her practice involves hours of surfing the net, mining for digital artifacts, and repurposing them as a way to reflect on and reinvent our relationship with interactive storytelling. McQuater won the Nuovo Award (plus an honorable mention for Excellence in Design) at the 2019 Independent Games Festival for her browser-based game Black Room. Her work has been exhibited internationally. McQuater lives and works in Los Angeles.

Gemma Fantacci: Visually, HALO is an eclectic assemblage. It features avatars from the Halo video game series as well as characters from Dream Stripper. This juxtaposition is striking, but it also brings to the foreground some of the dominant cultural tropes and motifs of videogame culture: the trivialization of death on the one hand and the depiction of the female body as a sexualized object, a trophy for the player’s fantasies, on the other. These avatars are not only subjected to the male gaze, but also partake to an endless loop of life and death, pleasure and domination. Can you describe the making of HALO, from conceptualization to execution? Why did you decide to mix these two different, yet contiguous video games to create your machinima series? How did you choose the elements that populate your video collages?

Cassie McQuater: Before starting HALO in 2016, I had recently finished a short, web-based chat bot game called Eliza. In Eliza, the titular character moves through her world stuck in T-pose. I was very new to animation and game making in general, and the idea of T-pose, which is the pose characters take before they are rigged and animated, with their bodies standing straight and their arms extended out to the sides, felt alien and almost sad to me – a reminder that these animated characters are just vessels for their animators in a sense. When you look at models in T-pose, you’re looking at something frozen in time – something about to happen, but not happening yet. I think I related to that on some kind of mental level, the feeling of being stuck, locked in place, and there was a certain touch of uncanny valley to it.

Stock animations can be purchased or downloaded for free, through sites and apps as Mixamo, and I found myself spending a lot of time looking at these animations, looping over and over, and thinking about what the actual crafting of various stock animations of things like “Idle,” “Dying,” “Female Sitting,” ect. says about how we perceive these actions in real life. There are so many death animations in video games. After a while they all looked the same, and watching the same animation loop over and over again (like a gif) made the action feel exponentially more mundane and trivial as it went on.

I became particularly interested in the stock animations labeled as “female” on these websites and apps, and particularly with the differences between the “male” and “female” poses. Most of the time they were obviously sexist, often to a comedic degree. In “Female Laying Pose,” for example, the human puppet is shown laying on her arched back, her leg extended in the air with the foot/toe pointed. It’s a completely unnatural pose, and yet someone decided that this pose would be popular enough to include as stock animation. Looking through these animations reminded me of the sometimes more subtle versions of sexism we consume in games – the poses, and actions, the animations, all reveal the way the characters’ bodies are tied to these tropes.

I explored that dynamic in HALO by combining, side by side, the overly-macho expression of the military science fiction game Halo with the uncomfortable gaze of Dream Stripper, their animations looping together forever in death, dodging, sitting, idling.

Gemma Fantacci: The peculiarity of your intervention is underlined by elements that are absent in the contexts of the respective sources. In these chaotic yet beautifully choreographed tableaux, we see flower petals falling from the sky, pinball machines, plants, furniture, abstract shapes and so on. And yet, even in this alternative reality, the avatars seem able to regain control over their bodies, grafting themselves into a completely different narrative. Are they finally free from the control of their puppet masters? Is machinima, then, the only way for video game characters to avoid top-down manipulation?

Cassie McQuater: I like the term you used here, grafting, which involves attaching a foreign object to another, in the hopes that the two will grow together and produce something new. I do think that removing these characters and their animations from their regular, in-game context has a way of freeing them, in a sense. By removing them from their context, they are allowed to be viewed in a more neutral state. You can see the absurdity of their animations, costumes, poses, more clearly. The masculine avatars are all constantly dying, while the avatars from Dream Stripper are constantly performing more active combinations. Instead of dancing though, they are dodging, they are swimming, they are diving, they are dreaming and staring at the sky. It’s a different dance.

Gemma Fantacci: GamePedia describes Dream Stripper in these terms: “the player controls the dancer. One decides how she dances, what she wears. […] As she dances, one can watch her expressions change, pause the dance, move the camera to watch from any angle, and change or remove her outfits.” Although this is nothing compared to some extremely degrading comments that can be found on online forums or in the comment section of YouTube videos, what strikes me is that the allure of the game is the ability of owning the female body. The player is given complete control of the object of his desideres. Unfortunately, this logic goes beyond the boundaries of videogames and permeates IRL as well. In a conversation with Valerie Amend about your browser-based “feminist dungeon crawler” Black Room (2019) you mentioned “the anxiety and fatigue of looking at hundreds of very sexulized women sprites daily”. In your ongoing investigation of the representation of female characters in games, did you identify turning points or specific patterns that have been normalized and accepted as “natural”?

Cassie McQuater: Yes, there are too many tropes to count, with varying degrees of sexism displayed in each. One of the most consistent and violent tropes I encounter in my work, I think, especially when I was working with vintage sprites in Black Room, is the female character’s dying or KO (Knockout) poses. When knocked out, women characters often collapse with legs spread open, backs arched, arms raised above their heads, and, especially in fighting games from the 1990s, their undergarments exposed. These poses, while the women characters are in an unconscious state, are sexulaized to a degree I still find startling, even after having seen hundreds of them.

There’s a character who I think illustrates a lot of these tropes succinctly: Yuri Sakazaki, from the Art of Fighting/King of Fighters series. She starts off as a damsel in distress in the first game of the series, and eventually becomes a fully playable character in the following games. She has a wide variety of sexist dying/KO poses, as expected — when she’s knocked out with a special move, her top is often torn off, exposing her bra. But what’s particularly tragic, to me, is that her winning poses use this effect too. In Capcom vs SNK 2, to quote from the SNK wiki: “...when Yuri finishes a fight with a “Finest KO” (finish with a super move as a counter to an opponent’s special or super move), she will attempt to tie her gi tighter. However, the belt becomes completely undone and her top opens, revealing a semi sheer undershirt. Yuri will then blush in total embarrassment and immediately cover herself.” Even when she wins, she loses.

A more subtle example of sexism that I encountered often in fighting games, specifically, can be found in the “character’s stats” or “about” sections. In more than one example, the age/weight categories for women fighters are left with things like: “???” or “No One Knows!” These very fit women characters, then, are still tied to the sexist trope of caring about their weight and age to an impossible degree. I have never seen this attribute in a male character's stats. Ever.

Gemma Fantacci: Your artistic production involves a variety of media, including digital images, video, video games and machinima. I am very interested in your relationship with video games. What are video games to you? Also, what makes you choose one medium over another in your investigation of a topic, a theme, or a trope? And why are you so fascinated by retrogaming, ludo-nostalgia, and sprite-based characters?

Cassie McQuater: Video games, to me, are a vehicle for storytelling. They ask the player to enter the medium, or story, as an active participant instead of a static viewer. There’s a kind of intimacy to that which I’m drawn to. It often feels like I’m taking an emotional risk, letting the player into something I’ve created.The work becomes as much about the player and their actions/reactions to the video game world as it is about my narrative or design. It’s a collaboration, then, between me and the player, the player who I will probably never meet IRL. To me, it feels like the most honest and personal way I can connect to my audience, my viewers, which is my goal as a storyteller.

Gemma Fantacci: In your practice, you often subvert pre-established narrative models within the game context, repositioning elements belonging to the game space or characters set aside or even objectified – e.g see the avatar from Dream Stripper in HALO. In doing so, you are unleashing the narrative potential of such elements and giving them a new status and, above all, a new space. Do you consider video games a new kind of folklore? Or more like a new kind of religion? (see next question)

Cassie McQuater: I do consider video games a kind of folklore. In games, we can learn about morals, about our perceived ideas of right vs. wrong, and about how our actions affect the (game) world around us. Fairy tales and folklore occupy a similar role, as they often have a contextual morality component to the narrative. I think this connection, at least to me, is perhaps most potent in JRPGs, which often use references to mythological figures and beasts, and feature a lot of elemental magic and weapons – the harnessing of the elements (fire, wind, water, ect) being another common theme in fairy tales. Playing Secret of Mana, a game where [spoiler!] the main protagonist is eventually revealed to be the son of a tree, feels a lot like reading a fairy tale to me.

Gemma Fantacci: The term “halo” has strong religious connotations, as it refers to the disk of light surrounding the heads of sacred figures, such as saints, in religious paintings. The same applies to the term “icon”, which is a representation or picture of a sacred or sanctified Christian personage, traditionally used and venerated in the Eastern Church. Your mesmerizing dioramas look like modern-day icons. Is my decoding “aberrant” or do religious elements are indeed present in this work and in your oeuvre tout court?

Cassie McQuater: The duality of the word “halo” in this work was the starting inspiration for me, and the theme of its duality was very intentionally explored. I liked the idea of “halo” being tied to both an extremely popular military science fiction video game franchise and as an aura of light surrounding a holy figure’s forehead. It’s a duplicity of meaning, a balance of hard and soft, which is reflected in the appearance of the characters – the heavily armored soldiers moving alongside the thinly clothed women. I suppose I think of the women characters as the heavenly figures in this scenario. In one scene, I have arranged a woman character with a golden ring (from the Sonic the Hedgehog series) floating over her head, a more direct reference to a halo.

Gemma Fantacci: Lastly, I would like to ask you about the role your grandmother played in your approach to video gaming. In several interviews you mentioned that she suffered from insomnia and that you kept her company while she played video games at night. It sounds like video games acted as a bridge, as a kind of intergenerational social bonding. A bit like fairy tales, but interactive. Is your artistic practice a way for you to rework these narratives with a critical eye, highlighting their influence on our lived life, now that you fully understand their logic and ideology?

Cassie McQuater: My grandmother did suffer from insomnia, and would stay up all night playing Zelda as a way to cope with it. We would have sleepovers, and there really wasn’t anything better as a small child than staying up all night, eating ice cream, and watching grandma beat the tough baddies for me. As a child, I wasn’t allowed to have a game console of any kind. Eventually, my parents capitulated and allowed my younger brother to get a GameCube. So, in a sense, he was allowed to have access to video games as a young child in a much more direct way than I was ever able to – I could only access video games through my grandmother. This set of interactions shaped my relationship with video games, and influenced my emotional attachment to them as a way of storytelling, and specifically as a woman who plays games. I love video games – but it’s important to be critical of the things you love, to allow them to grow and reach the potential you know is there.

HALO

digital video (1920 x 1080), color, variable lengths, 2016 (United States)

Created by Cassie McQuater

Originally commissioned by Electric Objects

Special thanks to Luca Miranda