LORENZO ANTEI

SONG TO SONG

MARCH 21-27 2022/21-27 MARZO 2022 (ONLINE)

Introduced by Matteo Bittanti

CLOUDS

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 2’ 08”, 2021, Italy

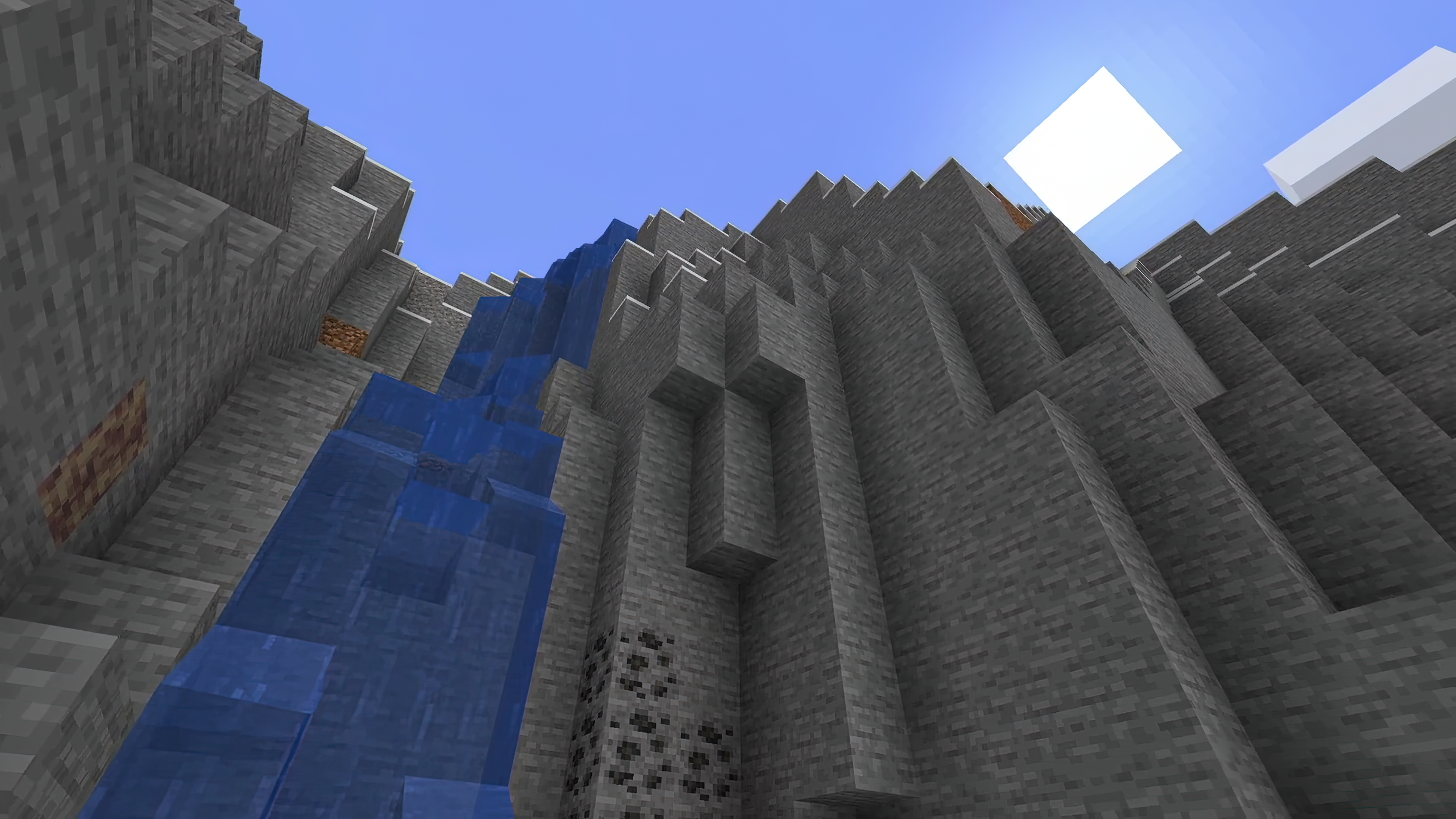

Clouds è un video musicale basato sulla canzone “Le nuvole” di Fabrizio De André realizzato con Minecraft.

Clouds is a music video based on Fabrizio De André’s song “Le nuvole” created with Minecraft.

L’ARTISTA

THE ARTIST

Lorenzo Antei è nato a La Spezia nel 1994. Si è laureato in Economia e Commercio all’Università di Pisa. Da studente si appassiona alla fotografia dopo uno stage a RadioEco, la radio universitaria per la quale realizza diversi servizi su eventi musicali. Dopo l’iscrizione all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara (NTA), inizia a lavorare con i media digitali, compresi i videogiochi. Filmmaker indipendente e montatore video, Lorenzo collabora spesso con istituzioni come teatri, locali musicali e musei

Lorenzo Antei was born in La Spezia in 1994. He received a B.A. in Economics and Business from the University of Pisa. As a student, he became fond of photography when interning at RadioEco, the college radio for which he produced several stories about music events. When he joined the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara (NTA), he began to work with digital media, including video games. An independent filmmaker and video editor, Lorenzo often collaborates with institutions such as theaters, music venues, and museums.

INTERVIEW

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe your relationship with video games in general and with Minecraft in particular? What attracted you to this video game and why did you use it to create Clouds?

Lorenzo Antei: I have a very intimate relationship with video games, which began at the turn of the century with a Game Boy Color, and was then followed by a personal computer — I disrupted my dad’s working sessions so many times — and by a Super Nintendo. During my childhood and early adolescence, I spent most days collecting and exchanging pirated games, taking part in countless LAN tournaments and reading magazines about gaming — things were so magical before websites became popular.

I have always been fond of cheating, not so much as a technique for gaining unfair advantage in video games— I hardly ever complete a game before abandoning it — but as a tool for deeper engagement with the game itself.

As I grew up, what I was looking for in games changed considerably. What originally was just a playful, escapism experience for me, the video game has now become a creative, meditative, exploratory practice. It is as if the game were a blank canvas, a space in which we can experience whatever we desire, whether it be orderly or chaotic, functional or useless, creative or destructive.

Today I spend less time on video games compared to other activities — at least, less than I really want to — but that short amount is much more intense than before. Over the years, the video game medium has undergone a significant evolution that has both positive and negative implications. To me Minecraft looks like the epitome of the medium’s potential for creativity. It made me (re)discover the pleasure of exploration in a world that can be endlessly reconfigured.

I chose Minecraft to create my machinima because it gives players the ultimate freedom: it is not a game that one plays to complete but an endless experience. It’s about living in a world where one can easily get lost. The pixelated world of each user is procedurally generated but random. Experiences within this game are governed by chance, the same chance that seems to govern the movement of clouds in our atmosphere.

Matteo Bittanti: What is machinima for you? A medium, an aesthetic, a format, or something else? How did you get to know this experimental practice? Do you think you will try again with machinima in the future?

Lorenzo Antei: Machinima began as a narrative medium. The original idea was to tell a story using video game assets. But nowadays, it has become something much more profound. It is a fully fledged artform, with its own conventions and iconography. I first encountered machinima when I was studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara (NTA). My “first time” was Jon Rafman’s Woods of Arcady and since then, I never looked back. I have developed several small projects and I am working on new ideas as we speak.

Matteo Bittanti: Can you describe the origins of Clouds? Why did you choose a song/poem by Fabrizio De André?

Lorenzo Antei: De André’s music has always been part of my upbringing. The singer-songwriter from Genoa, inspired by Aristophanes’ eponymous play, compares the clouds to the arrogance of the powers that be and that are “clouding” society, so to speak. In my interpretation, the clouds represent all those who denigrate the video game as an artform and label it as puerile form of entertainment. Obviously, I believe that the game medium is much more than mere escapism.

Inside Minecraft, through the use of meta-dialogue, two entities compare the video game experience with the everyday experience. Both contexts can teach us important lessons about life and are therefore both valuable.

The music and images animate the poem, which is narrated by a neural voice synthesizer. The images consist mainly of wide open views from Minecraft that extend to the horizon. The music echoes the original soundtrack, creating a lo-fi atmosphere that sounds both familiar and somber. The original tracks are by C418.

Matteo Bittanti: Is there anything you would like to add?

After the beginning of the pandemic, I started practicing in-game photography by exploiting the maps offered by sandbox games like Garry's Mod. That’s what I am exploring these days.

INTERVISTA

Matteo Bittanti: Puoi descrivere la tua relazione con i videogiochi in generale e con Minecraft in particolare? Che cosa ti ha attratto di questo videogioco? Perché lo hai utilizzato per realizzare Clouds?

Lorenzo Antei: Ho un rapporto decisamente intimo con i videogiochi. La relazione ha avuto inizio attorno al 2000 con un GameBoy Color a cui hanno fatto seguito un personal computer — ho rubato infinite sessioni di lavoro a mio padre — e un Super Nintendo. Durante la mia infanzia e prima adolescenza ho avuto il periodo più intenso dove le giornate si riempivano con lo scambio di copie pirata, le partite in multiplayer locale a schermo condiviso e le speculazioni leggendo magazine sul mondo videoludico (prima della diffusione delle webzine era tutto più magico).

Ho sempre trovato affascinante il cheating, non tanto come tecnica che facilita il completamento del gioco — difficilmente completo un gioco prima di abbandonarlo — bensì come strumento di esplorazione più profonda.

Crescendo è cambiato ciò che cercavo nei giochi. Da semplice esperienza ludica, il videogioco sta diventando per me uno sfogo creativo/libero/esplorativo. È come se il gioco fosse un canvas, in cui noi siamo liberi di rappresentare ciò che desideriamo, che sia ordinato o caotico, funzionale o inutile, creativo o distruttivo.

Oggi dedico meno tempo al videogioco — o almeno, meno di quanto vorrei realmente —, ma quel poco racchiude molta più qualità. Negli anni, il videogioco ha subito un’evoluzione che comprende sia elementi positivi che negativi. Minecraft ha il merito di rappresentare una di queste caratteristiche positive, facendo (ri)scoprire il piacere dall’esplorazione, in un mondo creato a nostra misura.

Ho scelto Minecraft perché offre la massima libertà: non è un gioco da completare ma un’esperienza da vivere in un mondo in cui ci si può perdere. Il mondo pixellato di ciascun utente è generato in modo procedurale ma randomico. Le esperienze all’interno del gioco sono regolate dal caso, lo stesso caso che sembra regolare il movimento delle nuvole nella nostra atmosfera.

Matteo Bittanti: Cos’è il machinima per te? Un medium, un'estetica, un formato, o qualcos’altro ancora? Come hai conosciuto questa pratica sperimentale? Pensi di cimentarti nuovamente con il machinima in futuro?

Lorenzo Antei: Ritengo che il machinima, partendo dal semplice pretesto di raccontare un videogioco, si sia codificato ed evoluto in qualcosa che va oltre, determinandosi in una forma d’arte autonoma dotata di una sua estetica.

Ho formalmente conosciuto il machinima con l’ambiguità grossolano/epica dell’opera di Jon Rafman, Woods of Arcady durante gli studi all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara (NTA).

Ho già realizzato qualche esperimento e sto sviluppando ulteriori progetti.

Matteo Bittanti: Puoi descrivere le origini di Clouds? Come descriveresti la relazione tra suono e immagine? Perché hai scelto un brano/poesia di De André per realizzare la tua opera?

La musica di De André fa da sempre parte del mio bagaglio culturale. Il cantautore genovese, ispirato dall’omonima commedia di Aristofane, paragona le nuvole alla prepotenza dei potenti, che oscurano la società nella nostra indifferenza. Nella mia interpretazione, le nuvole rappresentano tutti quelli che denigrano il videogioco e lo emarginano a puro intrattenimento infantile.

Proprio all'interno di Minecraft, attraverso un meta-dialogo, due entità cercano di paragonare ciò che viviamo all’interno di un videogioco con ciò che viviamo nel quotidiano, in quanto entrambi sono contesti capaci di farci vivere delle esperienze (positive o negative) che plasmano la nostra esistenza.

La musica e le immagini accompagnano il testo della poesia, narrata da un sintetizzatore vocale neurale. Le immagini sono costituite prevalentemente da ampie vedute aperte che si estendono fino all’orizzonte. La musica riprende la colonna sonora originale, creando un’atmosfera lo-fi tanto familiare quanto austera. I brani originali sono di C418.

Matteo Bittanti: C’è qualcosa che vorresti aggiungere?

Dopo l’inizio della pandemia, ho iniziato a praticare l’in-game photography sfruttando le mappe offerte dai giochi sandbox come Garry’s Mod. Questo è lo spazio che sto esplorando oggi.

CLOUDS

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 2’ 08”, 2021, Italy

Created by Lorenzo Antei

Courtesy of Lorenzo Antei

Director, editor: Lorenzo Antei

Text: Fabrizio De André

Music: C418

Made with Minecraft (Mojang Studios, 2011)