BEATRICE CARPINA

THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE AI

MARCH 21-27 2022/21-27 MARZO 2022 (ONLINE)

Interview by/Intervista di Luca Miranda

loneliness of the machine

machinima/digital video, color, sound, 10’ 00”, 2021, Italy

Creato con/in Red Dead Redemption 2, Loneliness of the Machine racconta la storia di un'intelligenza artificiale che diventa completamente senziente. Ora consapevole di sé, The Machine cerca un senso in un mondo simulato apparentemente criptico. Testando i limiti del mondo ludico, l’avatar cerca una risposta. Può il giocatore fornire un feedback utile?

Created with/in Red Dead Redemption 2, Loneliness of the Machine tells the story of an artificial intelligence that becomes fully sentient. Now self aware, The Machine seeks for meaning in a simulated world that appears cryptic. By testing the limits of the game world the avatar looks for answer. But can the player provide any kind of useful feedback?

L’ARTISTA

THE ARTIST

Nata a Pisa all’inizio del nuovo millennio, Beatrice Carpina (pron. Càrpina) studia all’Accademia di Belle Arti di Carrara, Italia. Loneliness of the Machine è il suo primo machinima nonché la prima partecipazione a un festival internazionale. Carpina vive e lavora a Pisa.

Born in Pisa at the beginning of the millennium, Beatrice Carpina (pron. Càrpina) is currently studying at the Academy of Fine Arts in Carrara, Italy. Loneliness of the Machine is her first attempt at machinima at the first submission to a festival. Carpina lives and works in Pisa.

INTERVIEW

Luca Miranda: On a visual level, Red Dead Redemption 2 remediates the style and conventions of cinema: the game’s artistic direction emphasizes the mood, atmosphere, and iconography of a recognizable genre. The direction of your work emphasizes the player’s point of view, using the virtual camera placed behind the avatar with sporadic aestheticizing interventions, for instance, in the sequence of the clouded sky. Why did you choose a visual style that closely mimics the source text, i.e., the video game?

Beatrice Carpina: The simplest answer — which informs my artistic direction in this machinima — is that such perspective perfectly mirrors the experience of how the player interacts with the video game. Therefore, the point of view I used can be perceived as more “natural” to the viewer. It also encourages the player to identify with her avatar, the ideal subject to whom the voice-over is addressed to, and this provides the possibility to see both points of view — that of the player and that of the entity staring at him — through the combination of video and text. The reshuffling of identities — a theme that I highlight in Loneliness of the Machine — is a commentary on the function that we assign to technology, and I believe that closely following the player’s point of view is conducive to this effort. The spectator identifies with the avatar, he is part of the game, but, as a spectator, he is not actually playing the game: thus, he can appropriate the external vision that belongs to the speaking entity because he is observing the player exactly as the latter operates within the game’s spaces. In a sense, this vision shows what the text doesn’t tell, in a way that a different point of view could not.

Luca Miranda: The narrator describes the simulated world — created specifically for the player/avatar/machine — as perfect, idyllic. The virtual environments of Red Dead Redemption 2 are among the most vivid and detailed in recent times. Did you select this specific game to create your machinima after producing a working script or was Red Dead Redemption 2 itself that stimulated a reflection about the meaning of artificial intelligence?

Beatrice Carpina: I selected the video game after writing a script, although I must admit that I had Red Dead Redemption 2 in mind from the very beginning as a setting for a possible machinima. The script was influenced by this possibility, at least in part: during the writing process, I was inevitably thinking of RDR2 lush landscapes, to the point that the virtual scenery concretely influenced my writing style. When I finished my script, the choice was somehow inevitable, because what I was looking for was exactly a video game that would convey a feeling of pastoral peace and immersion within the virtual world. Had I chosen a different video game, the contrast would have been perhaps more striking.

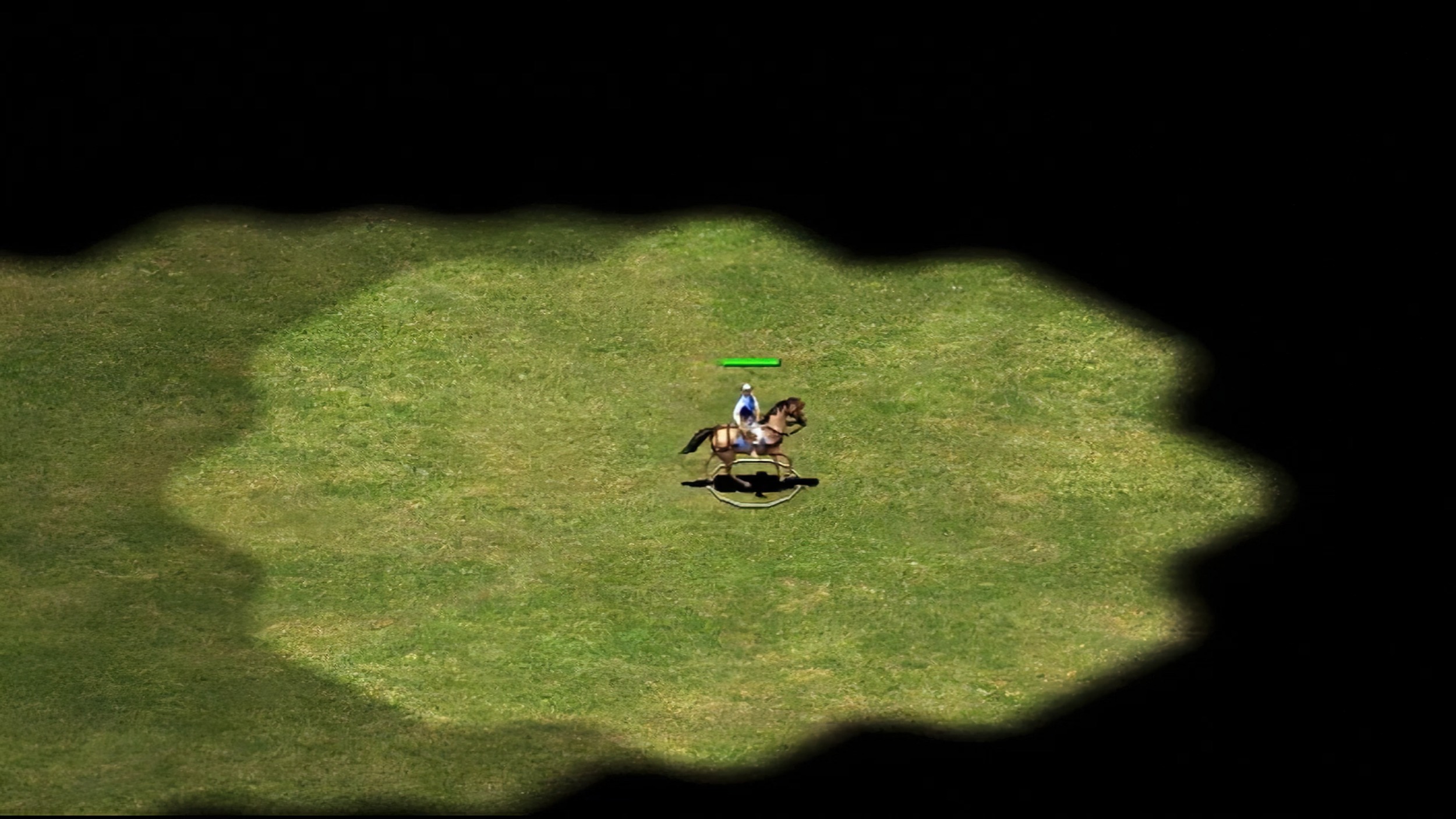

Luca Miranda: At one point, you switch to a second video game. Which game is it? And why did you include an isometric view?

Beatrice Carpina: That’s Age of Empires II. To be precise, it’s the 2013 HD remastered version, because the original CD-ROM that I bought in 2000 wasn’t working. I picked this game because I wanted to present an alternative perspective from that of the gamer, the “objective” vision of the video game, so to speak, the God’s eye view that discerns a series of recognizable patterns, producing a map with established boundaries, which if reduced to the bare minimum is nothing more than an empty plane.

Luca Miranda: In this section, you highlight the limits that characterize and define the video game experience: a procedural world that emerges in the darkness of the digital space when the player sees its limits and inevitably perceives its imposing force. What do these artificial-and-yet-non-negotiable boundaries mean?

Beatrice Carpina: Boundaries are an integral part of the world and of reality at large: the world we inhabit, IRL, is extremely limited and limiting. Nonetheless, it is only natural to look beyond the boundaries of what is allowed, and, in a sense, the digital world allows us to transcend some of these obstacles. I believe that limits and constraints are always present in any context. In Loneliness of the Machine, the limit per se is not what triggers the monologue. Rather, it is the over ambitious search of a player who should know better, a player wandering aimlessly, striving to assign some kind of meaning to his relentless journeying. This is, after all, the assumption from which the entity’s words begin: the certainty that the player always wants something more, something that he/she will not find within the video game because even the digital is finite. That said, I think it is appropriate to distinguish what the border represents in the world of video games from what the border means in the virtual reality in which we immerse ourselves every day: in a digital world now largely determined by algorithms and rules — “limits”, if you will — that are becoming increasingly narrow and precise, we must understand which are the real limits of an experience and which the fictitious ones that are imposed arbitrarily, for purposes that go beyond our knowledge.

Luca Miranda: Do you think that it is possible to use a perspective that looks at the player’s experience as an imperialist and colonialist History of video game spaces?

Beatrice Carpina: I don’t know how much the player’s experience can be compared to an imperialist and colonialist History: rather, the video game is an environment created as a simulation of reality, and the player acts in this environment as if he/she were the only protagonist. The “conquest" of new territories does not actually presuppose the revolutionary aspect of the game in ways that had not already been foreseen: we could say that, therefore, the player is another character in the story, and that his/her moves are programmed, taken into account, by the game world itself. Like a pawn, the player moves by doing what he has to do, exploring as much as he is allowed to: this is the deal, take it or leave it. When he/she moves in non-predetermined ways, he ends up going beyond the game, becoming the creator of his own path and goal, and consequently he/she no longer belongs to the world that has been designed as a container for his/her experience.

Luca Miranda: It struck me that the voice-over in your machinima can potentially assume different roles: it’s the voice of the artist (player and narrator), or of the avatar, or of the ethereal entity that accompanies the player and the avatar on their journey. Were you thinking about this aspect, that is, the constant shuffling of roles and identities? What or who is talking to us? Can you elaborate on the identity of the narrator?

Beatrice Carpina: The text was actually born from a rather playful and unpretentious question: if the video game became self-aware, what would be its thoughts for the player? What role would he play? How would he see and understand his own existence? We can say that the speaking entity is the video game consciousness, which for the sake of brevity I improperly call “Machine”, which, trapped within itself, cannot help but feel as a creator and creature, the only thinking entity (besides the player) in a world of puppets of which “It” itself pulls the strings. As I was thinking about the premise of the text, I was inspired by Giacomo Leopardi’s Dialogue of Nature and an Icelander, not so much in theme as in form: an encounter between a divinity — who, unlike Leopardi’s Nature, was born to be at the service of the player — and the human being, driven by his own incessant search. Loneliness of the Machine subverts Dialogue between Nature and an Icelander, transforming Leopardi’s text into a monologue in which the two entities explore their relationship, and it is the divinity, the “Machine”, imploring the player to stay, to give it a reason to exist. Although the text was meant to be understood from the point of view of the “Machine”, it is clear that the roles are somehow intertwined: after all, the video game is the very world in which the player acts, it is the avatar that he controls, it is the system of rules in which he can move. The consciousness of the “Machine” has the features of the universal divinity, it is a concept that goes beyond a single and precise entity, although it speaks as a singular being.

It is also a commentary on what we are when we immerse ourselves in the digital world: what do we become, if not part of the digital world itself?

Luca Miranda: Within the field of game studies, video games are often described as a tripartite system consisting of machine (or console), software (the game) and player, with explicit rules and objectives defining the interactive experience. However, you have adopted a very different perspective, one in which the video game is defined as a sentient entity, needing to establish a contact with the player. A much more dialogical approach. What pushed you to develop this alternative way of understading the interactive between the player and the video game?

Beatrice Carpina: Actually, Loneliness of the Machine has a very personal meaning for me, but the idea behind the work was to explore our relationship with technology, what it represents to us. With an inverted perspective, making the “Machine” speak of the desires that perhaps we are projecting on it, I tried to analyze the way in which a sentient entity, rather than mere technology, could enact this relationship. As you can guess from the year in which it was made, I conceived Loneliness of the Machine in the midst of a global pandemic, when the role of the digital world underwent a radical change in our lives: the impossibility of physically seeing people, the compulsion to experience our affections through a screen, radically changed the very meaning of the virtual world. My research then turned to this new way of experiencing not only the video game, but the entire digital domain. Obviously, even the loneliest aspect of the pandemic has been translated into this work, and I believe that here lies, to some extent, the identity fusion between the “Machine” and the player: the way in which the virtual world has become our only source of affection, the way in which, not only by necessity but also by our nature as human beings, we are bound to what the digital represented, even more than we were before.

INTERVISTA

Luca Miranda: Sul piano visivo, Red Dead Redemption 2 sfrutta sapientemente gli stili e le forme specifiche del linguaggio cinematografico: la direzione artistica del videogioco evidenzia scenari e atmosfere tipici di uno specifico genere audiovisivo. La regia della tua opera enfatizza il punto di vista del giocatore, sfruttando la camera virtuale posta alle spalle dell’avatar con rari interventi estetizzanti, per esempio, le inquadrature del cielo annuvolato. Quali sono le motivazioni che ti hanno spinto a scegliere un percorso visivo contiguo a quello del testo sorgente, ovvero il videogioco?

Beatrice Carpina: La risposta più semplice — che forse è il fulcro della mia scelta — è che il videogioco viene vissuto in questo modo. Una visuale che appare più “naturale” permette allo spettatore di immedesimarsi nel giocatore, ovvero l’ideale soggetto a cui la voce fuoricampo si rivolge, e questo fornisce la possibilità di vedere entrambi i punti di vista — quello del giocatore e quello dell’entità che lo osserva — attraverso l’unione del video e del testo.

Il rimescolamento delle identità è una tematica che ho sviluppato in Loneliness of the Machine anche come riflessione sul ruolo che attribuiamo alla tecnologia e credo che seguire il punto di vista del giocatore, come scelta registica, aiuti a evidenziare questa ricerca. Lo spettatore si immedesima nell’avatar, è partecipe del gioco, ma, in quanto spettatore, non sta giocando: in questo modo riesce a fare sua anche la visione esterna, quella dell’entità che parla, perché egli sta osservando il giocatore esattamente come fa quest’ultima. In un certo senso questa visione racconta ciò che il testo non dice, in un modo che un punto di vista diverso non potrebbe fare.

Luca Miranda: La voce fuori campo descrive più volte il mondo simulato – creato appositamente per il giocatore/avatar/macchina – come perfetto, idilliaco. Gli ambienti virtuali di Red Dead Redemption 2 sono tra i più ricchi e dettagliati nel recente panorama videoludico. La scelta di realizzare l’opera all’interno di questo videogioco è stata dettata dal testo narrato in sottofondo oppure è Red Dead Redemption 2 in quanto tale ad aver ispirato la riflessione di Loneliness of the Machine?

Beatrice Carpina: Ho scelto il videogioco solamente dopo aver scritto il testo, anche se devo ammettere di aver avuto in mente Red Dead Redemption 2 come ambientazione per un machinima da molto più tempo. Si può dire che il testo sia stato influenzato da questa idea, almeno in parte: durante la scrittura il mio pensiero andava agli ambienti estremamente ricchi di questo titolo, tanto che alcune delle frasi che ho utilizzato vi fanno riferimento quasi direttamente. Alla fine della stesura si è trattato di fare una scelta che ormai per me era già ovvia, anche perché quello che cercavo era esattamente un videogioco che trasmettesse una sensazione di idillio e di immersione nel mondo virtuale. In questo modo il contrasto con l’altro videogioco che ho utilizzato sarebbe stato ancora più accentuato.

Luca Miranda: Nel tuo machinima ad un certo punto mostri un videogioco in visuale isometrica. Di che titolo si tratta?

Beatrice Carpina: Il secondo titolo da me scelto è stato Age of Empires II e, per la precisione, la versione rimasterizzata in alta definizione del 2013, dopo che il CD-ROM della mia versione del 2000 è diventato inutilizzabile. Ho scelto questo titolo per rappresentare una visione diversa da quella del giocatore, la visione oggettiva del videogioco come schema preciso: una mappa in cui muoversi, con confini stabiliti, che se ridotta all’osso non è altro che un piano vuoto.

Luca Miranda: In questa sezione espliciti i limiti che caratterizzano e definiscono la costruzione di un’esperienza videoludica: un mondo procedurale che si delinea nell’oscurità dello spazio digitale nel momento in cui il giocatore ne intravvede (e cozza contro) i limiti. Che significato attribuisci al ruolo di questi confini artificiali eppure non negoziabili nelle esperienze digitali di cui fruiamo?

Beatrice Carpina: I confini sono qualcosa di imprescindibile nel mondo tangibile e nella realtà, e questo vale anche per la dimensione virtuale che ure non dovrebbe averne: la realtà che viviamo ogni giorno IRL è estremamente limitata. Ciononostante, è innegabile che sia nella natura umana guardare oltre i confini del consentito, e, se vogliamo, il mondo digitale è un mezzo per travalicare alcuni di questi. Il limite di un’esperienza è per me qualcosa di semplicemente presente, senza una particolare connotazione di sorta: anche in Loneliness of the Machine non è tanto il confine del videogioco ad essere la causa scatenante del monologo, bensì lo è la ricerca smodata del giocatore che si spinge fin dove sa di non poter arrivare, fino a girare senza più meta nella speranza di trovare un significato al proprio vagare. E questo è, in fondo, il presupposto da cui partono le parole dell’entità: la certezza che il giocatore voglia qualcosa di più, qualcosa che, però, non troverà all’interno del videogioco perché si tratta di una realtà finita, una realtà che ancora è troppo limitata.

Detto questo, penso che sia opportuno dividere ciò che il confine rappresenta nel mondo dei videogiochi da quello che è il confine nella realtà virtuale in cui ci immergiamo ogni giorno: in un mondo digitale ormai in gran parte determinato da algoritmi e da regole, “limiti”, se vogliamo, che si fanno sempre più stretti e precisi, diventa necessario cominciare a distinguere quali di questi siano i limiti reali di un’esperienza e quali quelli fittizi che ci vengono imposti arbitrariamente, per obiettivi che vanno al di là delle nostre conoscenze.

Luca Miranda: Secondo te, è possibile adottare una prospettiva che guarda all’esperienza del giocatore come a una Storia imperialista e colonialista dei territori del videoludico?

Beatrice Carpina: Non saprei quanto si possa paragonare l’esperienza del giocatore ad una Storia imperialista e colonialista: piuttosto, il videogioco è un ambiente creato come simulazione della realtà, e il giocatore che vi si trova dentro si muove in questo ambiente come unico protagonista. La “conquista” di nuovi territori non presuppone in realtà il rivoluzionamento del gioco in modi che non fossero già stati previsti: potremmo dire che, quindi, il giocatore è un altro personaggio della storia, e che le sue mosse vengano programmate, messe in conto, dal mondo di gioco stesso. Come una pedina, il giocatore si muove facendo quello che deve fare, esplorando quanto gli è concesso: questo è il patto. Quando si muove in modi non prestabiliti finisce per andare oltre al gioco, diventa creatore del proprio percorso e del proprio obiettivo, e di conseguenza non appartiene più al mondo che è stato ideato come contenitore per la sua esperienza.

Luca Miranda: La voce fuoricampo interpreta potenzialmente tre ruoli: quello dell’artista (giocatore e narratore), quello dell’avatar, oppure quello dell’entità fantasmatica che accompagna il giocatore e l’avatar nel loro viaggio. Questa è stata una delle riflessioni che hanno accompagnato la produzione dell’opera, ovvero il miscelamento e ridimensionamento dei ruoli e dei piani identitari nella relazione tra le figure menzionate? Con che criterio hai sviluppato il testo che possiamo ascoltare e che si innerva lungo la struttura del machinima? Cosa o chi ci sta parlando?

Beatrice Carpina: Il testo a dire il vero è nato da una domanda piuttosto giocosa e priva di pretese: se il videogioco divenisse cosciente di sé, quali sarebbero i suoi pensieri per il giocatore? Quale ruolo ricoprirebbe? Come vedrebbe la propria esistenza? Si può dire che l’entità che parla è proprio la coscienza del videogioco, la quale per brevità chiamo impropriamente “Macchina”, che, intrappolata all’interno di se stessa, non può fare a meno di sentirsi creatrice e creatura, unica entità pensante (oltre al giocatore) in un mondo di marionette di cui è “Essa” stessa a muovere i fili. Dopo aver pensato alla premessa del testo, l’ispirazione per la sua impostazione è stato il Dialogo della Natura e di un Islandese di Giacomo Leopardi, non tanto nella tematica quanto nella forma: un incontro tra una divinità (che, al contrario della Natura leopardiana, è nata per essere al servizio del giocatore) e l’essere umano, spinto dalla propria ricerca incessante. Loneliness of the Machine sovverte quello che è stato il Dialogo della Natura e di un Islandese, lo trasforma in un monologo in cui le due entità esplorano la relazione che hanno l’una con l’altra, e sarà la divinità, la “Macchina”, a implorare il giocatore di restare, per darle ancora un motivo per esistere. Nonostante il testo sia stato scritto per essere inteso dal punto di vista della “Macchina”, è chiaro che i ruoli siano costretti a mescolarsi: dopotutto, il videogioco è il mondo stesso in cui agisce il giocatore, è l’avatar che egli controlla, è il sistema di regole in cui gli è possibile muoversi. La coscienza della “Macchina” è qualcosa che ha i caratteri della divinità universale, è un concetto che va oltre un’entità singola e precisa, nonostante parli come essere singolare. È anche una riflessione su quello che siamo quando ci immergiamo nel mondo digitale: che cosa diventiamo, se non parte del mondo digitale stesso?

Luca Miranda: Nell’ambito della disciplina che studia i videogiochi, altrimenti nota come game studies, il videogioco è spesso descritto come un sistema tripartito composto da macchina (o console), software (il gioco) e giocatore, in cui il rapporto con quest’ultimo è definito da regole ed obiettivi. È interessante come invece tu abbia adottato una prospettiva decisamente diversa, in cui il videogioco è definito come un’entità senziente, bisognoso di stabilire un contatto con il giocatore. Che cosa ti ha spinto a sviluppare questo approccio in particolare?

Beatrice Carpina: A dire il vero, Loneliness of the Machine ha un significato anche molto personale per me, ma l’idea con cui ho sviluppato il lavoro è stata quella di esplorare il nostro rapporto con la tecnologia, quello che per noi questa rappresenta. Con una prospettiva rovesciata, mettendo in bocca alla “Macchina” le volontà che forse siamo noi a proiettare su di essa, ho cercato di analizzare il modo in cui un’entità senziente, al posto della tecnologia, potrebbe vivere questo rapporto.

Come si può intuire dall’anno in cui è stato realizzato, ho ideato Loneliness of the Machine in piena pandemia, quando il ruolo del mondo digitale ha subito un radicale cambiamento nelle nostre vite: l’impossibilità di vedere fisicamente le persone, la costrizione a vivere i nostri affetti attraverso uno schermo, ha rivoluzionato quella che è la concezione generale del mondo virtuale. La mia ricerca quindi si è rivolta a questo nuovo modo di esperire non solamente il videogioco, bensì tutto l’universo digitale.

Ovviamente anche l’aspetto più solitario della pandemia si è tradotto in questo lavoro, e credo che stia qui, in qualche misura, la fusione identitaria tra la “Macchina” e il giocatore: il modo in cui il mondo virtuale è diventato la nostra unica fonte di affetti, il modo in cui, non solo per necessità ma anche per nostra natura di esseri umani, ci siamo legati a ciò che il digitale rappresentava, ancor più di quanto lo fossimo prima.

loneliness of the machine

machinima/digital video (1980 x 1020), color, sound, 10’ 00”, 2021, Italy

Director, Writer, Producer: Beatrice Carpina

Made with Red Dead Redemption 2 (Rockstar Games, 2018) and Age of Empires II (Ensemble Studios/Microsoft, 1999)